The Doge was the only position in the Venetian state which existed from the earliest times until the end of the Republic.

He was the nominal head of the Venetian Republic. In the earliest period, the doge wielded at a lot of power, both civilian and military, which inclined many of the early doges to try to turn the position hereditary.

The wealthy and influential merchant class opposed this tendency, and gradually hollowed out the position, until the Doge was a mere figurehead in the late Republic.

This process of reigning in the power of the earliest doges led to the creation of the Consiglio del Doge — a group of initially two, later six patricians, elected for short terms, without whose consent the Doge couldn’t act — and then the Consiglio Maggiore which later became the holder of sovereignty.

The position of Doge remained elected until the end, but to avoid manipulation, the election process became increasingly complex over the centuries. Even as the role lost political importance, it remained contested, and the Venetian ruling elite never allowed any one family to monopolise the title.

Why a doge?

The doge was there at the beginning of the republic, and even before that.

In the late Roman, early Byzantine Empire, the military forces in a province were led by a Dux, which simply means a leader. The Dux was both civilian administrator and leader of the local garrisons.

The Byzantine title Dux became the Venetian Doge, the Italian Duca and the English Duke. The area controlled by a Dux became a Dogado, a Ducato and a Duchy, respectively.

Normally, the imperial government appointed the Dux among the local dignitaries. However, at times in some provinces the empire left it to the locals.

As Byzantine influence waned, especially after the loss of Ravenna to the Lombards in 751, the Venetian elite simply elected their Dux themselves.

The birth of Venice

The Venetian state didn’t start with an assembly, a vote, a declaration or just some kind of formal act.

The reason was that the earliest Venetians were Byzantines. They didn’t want independence, and they didn’t need independence from Constantinople. They wanted to be a part of Byzantium.

The Roman and Byzantine province of Venetia et Histria had been almost entirely overrun by the Lombards in the 700s. Only the extensive lagoon areas from Grado in the north to Capo d’Argine (Cavarzere) in the south remained under Byzantine control. Most of the Byzantine land-owning class from mainland Venetia had fled into the lagoons, which became the Dogado.

Early Venice therefore needed Constantinople. The Dogado came about exactly because the wealthiest citizens of Venetia wanted to be Byzantine, and voted with their feet confronted with the Lombard expansion.

Even as the Dogado acquired de facto independence — in large part due to the absence of Byzantium — the Venetian state remained nominally under Byzantine suzerainty for centuries.

No written constitution

Due to the way the Venetian state started, there was no formal constitution. There were also no formal rules to limit the power of the doge or even to establish a basic procedure of succession.

As leaders of the navy and the military, the early doges had a lot of power over the affairs of the state.

Many appointed their oldest son or a brother co-ruler as one of their first decisions in office, in obvious attempts at securing a succession within the family.

Several dominant families, such as the Galbaio, the Partecipazio, the Candiano and the Orseolo, dominated the nascent state, and contested the powerful position of Doge between them.

This often ended in violence. Many of the early doges died a violent death in fights between the different factions of the aristocracy. The victors would depose, sometimes kill, and sometimes blind and force the ex-doge into a monastery.

Resolving political problems with physical violence is dangerous and generally not good for business. Getting killed in such a fight is particularly bad for business.

The Venetian elite therefore sought ways of limiting the role of violence in politics, and such violence centred on the powerful position of Doge.

Checks and balances

Several institutions appeared early in Venetian history, to keep a check on the power of the Doge. Over time, these checks and balances hollowed out the position of the doge, which became nothing more than — as some called it mockingly — the inn sign of the Republic.

The Promissione Ducale

Even in Antiquity, newly elected magistrates swore an oath on entering office.

There can be no doubt that the same thing happened in Venice from the very beginning. After all, the first doges were elected officials in a Roman/Byzantine cultural context, so the rules and traditions were the same.

This spoken oath became formalised in a document the new doge had to sign when he assumed office. It became known as the promissione ducale — the promise of the Doge.

The first extant promissione ducale is from 1192 for Enrico Dandolo, but there’s little reason to believe it was the first. By the mid-1200s, the structure of the document was more or less established.

The promissione grew over the centuries. The earliest documents are about a dozen pages, while the promissione of the last doge of Venice, Ludovico Manin, was a document of over three hundred pages.

Such an increase in the length of the document is emblematic of the hollowing out of the position of Doge.

The Consiglio del Doge

Very early on, the Concio — the popular assembly electing the early doges — imposed two councillors on the newly elected doge. Four more soon joined them, so there was one from each of the six sestieri.

These Consiglieri del Doge were elected for short terms — one year at a time — so they wouldn’t accrue personal power nor become dependent on the doge.

With the creation of the Consiglio Maggiore — the Greater Council — the Council of the Doge acquired other names, such as the Minor Consiglio — the Smaller Council — or the Serenissima Signoria — The Most Serene Lordship.

The promissione ducale usually included terms that the doge couldn’t take decisions of war and peace, or international relations in general, with the consent of his councillors. He wasn’t allowed to open diplomatic dispatches or receive ambassadors, without the presence of the councillors. They, however, could open dispatches and receive ambassadors, without the Doge present.

Much of the day-to-day business of running the highest level of the state fell to the Council of the Doge, and it was the closest thing Venice ever had to an executive or a government as we would recognise it.

The short term in office left the Councillors of the Doge dependent on the Maggior Consiglio, which thereby maintained its power and control over the Doge.

The Election of the Doge

The Concio — a popular assembly which however soon became dominated by the wealthy merchant class — elected the earliest doges.

With the establishment of the Maggior Consiglio in 1172 — as an exclusive body of that wealthy merchant class — it took over the election of the Doge.

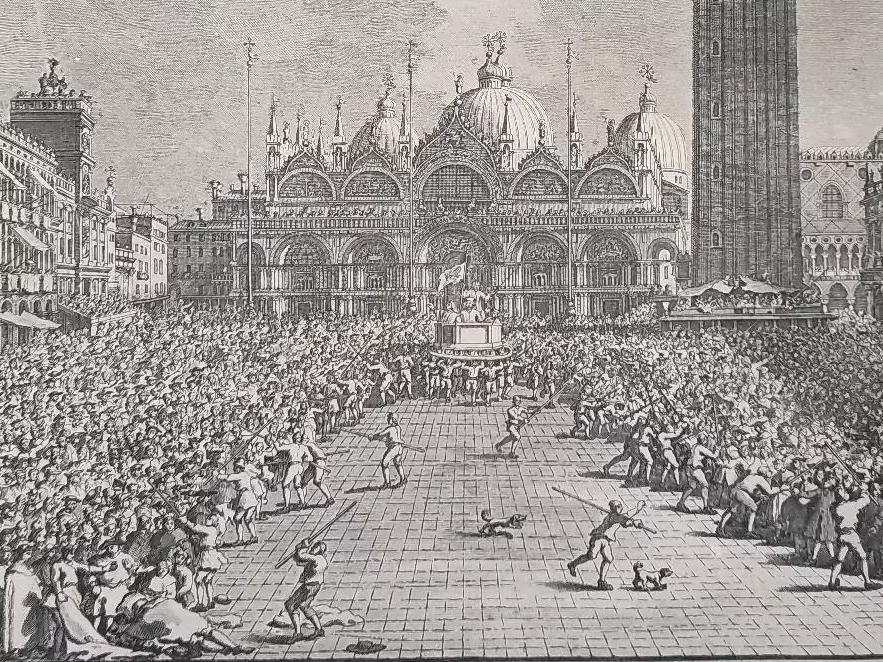

As a remnant of the earlier — more popular election process — the senior member of the council presented the new Doge to the people below from the balcony of the Doge’s Palace with the words “This is your new Doge, if he pleases you?”

That wording still left a semblance of the final decision with the people, even if it was only symbolically. After the formal abolition of the Concio in 1423 the words changed to a simple announcement of “We have chosen such-and-such as Doge.”

The final election process

The electoral procedure with the Maggior Consiglio changed several times, always becoming more indirect, to exclude manipulation of the process by powerful groups with the council.

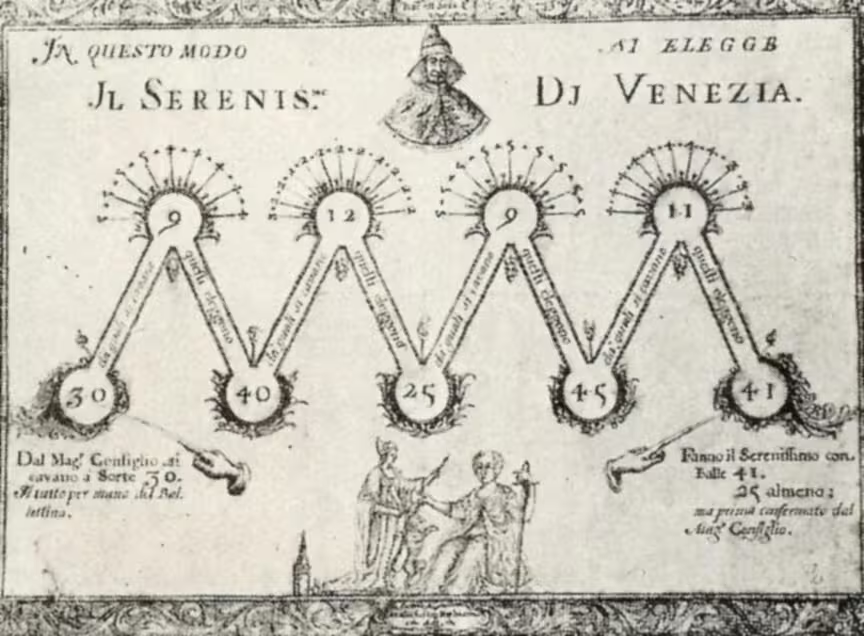

It found its final form in 1268 with several rounds of elections of committees whose members were then reduced by lot, until a final council of 41 patricians elected the Doge.

First, the Greater Council selected a group of thirty members by lot.

This group was reduced to nine by lot. These nine men elected a group of forty, each with a required majority of seven votes. The group of forty was reduced to twelve, again by lot.

The twelve chose, with a majority of nine, a new group of twenty-five, reduced to nine by lot.

The nine elected forty-five, majority of seven, reduced to eleven by lot.

These eleven men, majority of nine, elected the final group of forty-one men, who chose the new doge. The required majority was of twenty-five votes.

The power of the Doge

Even if the position of the Doge was left without much formal power over the state, the Doge still wielded a lot of influence.

The Doge, usually together with his councillors, presided over most of the major political and judicial organs of the state. They presided over the Maggior Consiglio, the Pregadi (the Venetian Senate) and many other commissions and magistracies with law-making powers.

He was therefore at the very centre of the political decision-making, and physically present everywhere that mattered.

He could even suggest new laws, also without the consent of his councillors, in any commission or magistracy he presided. All he had to do was stand up, remove the corno ducale from his head, and argue his case.

The title of Doge was the highest position a Venetian patrician could aspire to, even if the role didn’t have the same powers as their earliest predecessors.

Sources

- Doge in the ASV Indice

- Doge in the Lessico Veneto

- Dose in the Dizionario

- Minor Consiglio — ASV Indice

- Consiglio del Doge — Lessico Veneto

- Signoria — Dizionario

- Maggior Consiglio — ASV Indice

- Maggior Consiglio — Lessico Veneto

Related articles

- Doges of Venice

- State institutions of the Republic of Venice

- Chronology of major Venetian state institutions

- However, we’ll make another — newsletter

- The Consiglio Maggiore

- The Venetian constitution

- John Adams on the Venetian constitution

Leave a Reply