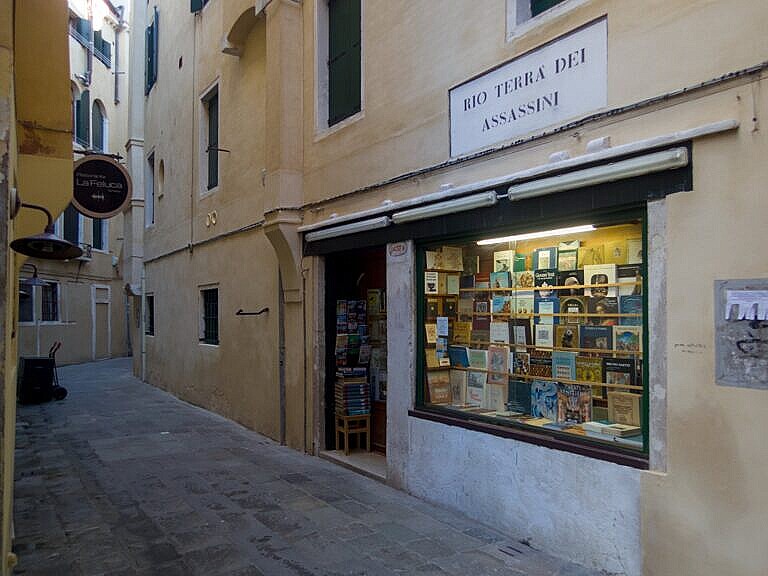

In Venice, between the Campo Manin and the Campo Sant’Angelo, there’s a little — and little used — alleyway with some unusual bends. That it often a sign that it was once a waterway of some kind. The canal is in fact a rio terà.

Rio terà in Venetian literally means a filled-in canal — terà as in Italian terra, earth or dirt, hence interred — so the alleyway was once a canal, a rio in Venetian. It was interred in 1791.

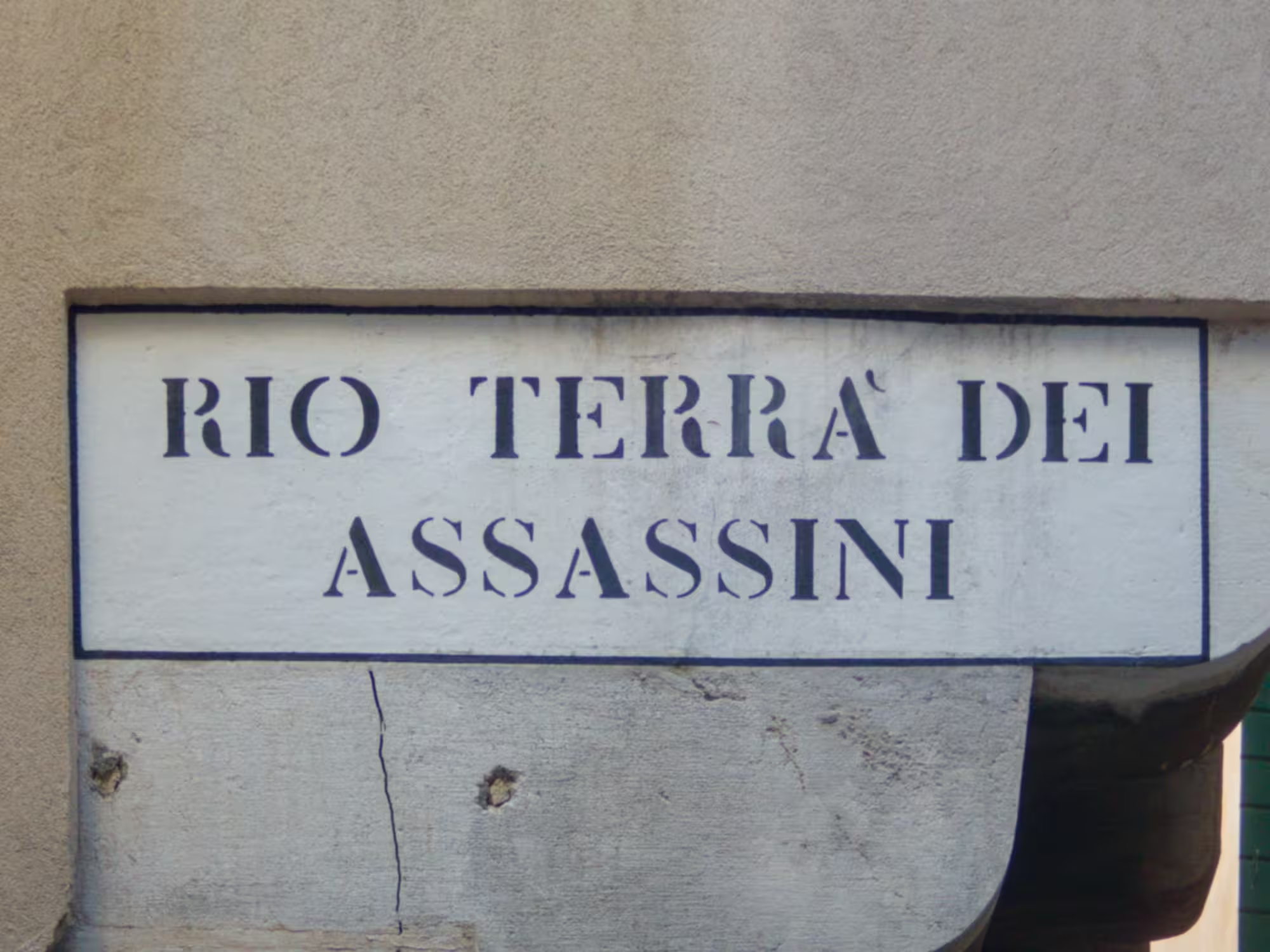

The full name is currently Rio Terà dei Assassini, but originally it was the Rio dei Assassini. Where it intersected the Calle dei Assassini was once a bridge, the Ponte dei Assassini.

The word assassini is not a false friend in English. It actually means assassins, as in murderers, killers.

We therefore had the canal of the assassins, the alleyway of the assassins, and where they met was the bridge of the assassins.

Murder, he wrote …

As is often the case, Giuseppe Tassini in his Curiosità Veneziane, comes to the rescue. In the entry for Assassini he quotes an unnamed chronicler:

Ancora sotto questo doxe se usava pur assae barbe postice alla greca, de sorte che veniva fatto de gran male la notte, e massime nelli passi cantonieri, come Calle della Bissa e Ponte dei Sassini, che si trovava molti ammazzati, e non si sapeva da chi fossero stati, perché non si conoscevano i malfattori, et per il dominio furono bandite dette barbe sotto pena della forca che no se le portasse nè di dì, nè di notte, e così si dismesse. Et fu ordinato che per le contrade mal secure fossero posti cesendeli impizadi che ardessero tutta la notte, dove furono poste le belle ancone. Et questo tal cargo fu dato alli piovani, e la Signoria pagava le spese.

In my artisanal translation from the Venetian:

“Still under this Doge people used to wear false Greek beards, and the result was a lot of evil-doing by night, and mostly in the dark alleyways, like Calle della Bissa and Ponte dei Assassini, where many killed were found, and nobody knew who had done it, because the wrongdoers couldn’t be recognised, and the state banned the said beards under penalty of the gallows, that no-one should wear them neither by day nor by night, and in that way it ended. It was ordered that in the less safe areas lamps were hung, that burned all night, where the beautiful icons were placed. And this charge was given to the parish priests, and the Lordship paid the expenses.”

A few explanations

There’s still a few things to unpack, even in the translation.

The Doge in question is Domenico Michiel, the 35th doge of Venice, who ruled approximately 1116-29. The years are not entirely certain due to the scarcity of records from the period.

A “Greek beard” means a full beard. It is a reference to how ancient Greek philosophers were traditionally depicted.

The Calle della Bissa is near the Rialto.

The expression il dominio means the state or the government. Likewise the Signoria means the government.

The belle ancone refers to the many small shrines on the walls in Venice. The Venetian word ancona comes from the Greek eikòn, which in English has become icon. The little square L’Anconeta on the modern Strada Nova has its name after a medieval icon in a now lost oratory.

These small shrines are often situated in dark little alleyways, exactly for this reason. A robbery or a murder in a dark alleyway was a crime against the laws of the state. However, the same crime under a divine image, an ancona or icon, became a crime against the divine too. The shrines were a protection for the place and the people passing, but also as a deterrent against any wrong-doing near the presence of the divine.

The piovàni means the parish priests in their role as custodians of the rain water in the public cisterns. In Venetian rain is piova.

Rio di Ca’ Pesaro

Apparently, in the Middle Ages, there was a spate of murders in central Venice, in various dark alleyways. The authorities couldn’t find the culprits, who disguised themselves wearing fake full beards, so they put a death penalty on wearing fake full beards.

This is roughly what Tassini tells us, based on an unnamed chronicler.

The current name is undeniably there for anyone to see, as should be evident from the photographs above.

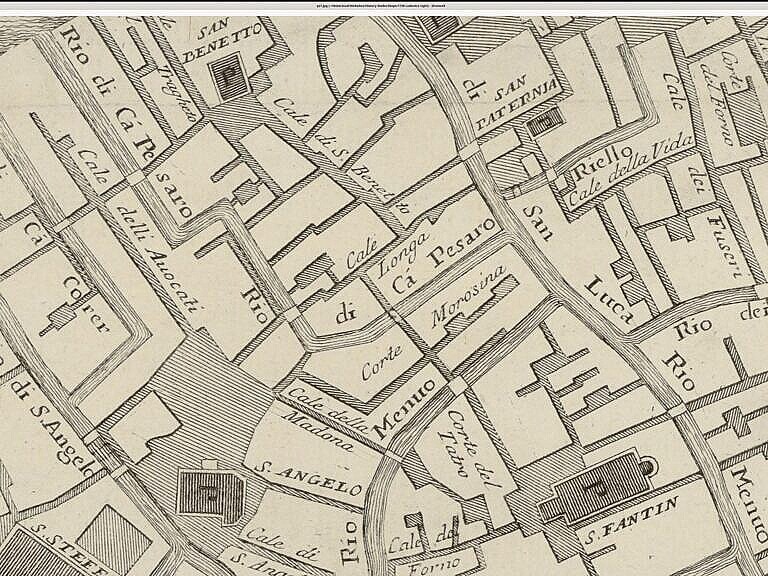

However, if we look at some of the old maps of Venice, it is not so clear.

Coronelli, in his guide to Venice from 1697, lists all the bridges of the city, and our canal and bridge appears as Rio di Ca Pefaro à S.Benetto va in Rio Menuo. No assassins here.

A French map of the canals and bridges of Venice, by Herman van Loon (1725), shows the canal, but doesn’t name it. The bridge, on the other hand, is here P. des Petites Pierres — the Bridge of Small Stones.

The best map we have from before the interment of the canal, is the map by Ludovico Ughi from 1729. The canal is clearly on the map as Rio de Ca’ Pesaro. The name Assassini doesn’t appear on the map at all.

On a map from 1808, by Teodoro Viero, the canal is partially filled in, but it is still the Rio di Ca’ Pesaro. No assassins.

Assassins or Ca’ Pesaro

Which is it, then: Rio dei Assassini or Rio di Ca’ Pesaro?

I don’t have a definitive answer, but my best guess is that the official name always was Rio di Ca’ Pesaro. It appears on maps and in travel guides spanning well over a century, and there are no mention of the Assassini.

It is equally likely that the most people in Venice referred to the canal and the bridge by the more interesting — and more unique — name of Rio dei Assassini.

The Pesaro family owned palaces in several places, so the name Rio di Ca’ Pesaro might easily have been ambiguous or just unclear. The best known Ca’ Pesaro today is on the other side of the Grand Canal, in the Sestiere San Polo. It is now a civic modern art museum.

There was a major reform of place names in Venice in the 1880s, partly influenced by Tassini‘s work which resulted in the publication of Curiosità Veneziane. It is not unlikely that the official name changed on that occasion.

The Toy Bridge

Such discrepancies in placenames in Venice is not unusual. The bridge of San Giovanni Grisostomo was the Ponte dei Zogatoi (Ponte dei Giocattoli in Italian) for generations. The local administration changed the official name of the bridge a few years back by popular demand.

The new name literally means the “Toy Bridge”, because there used to be a toy store at the foot of the bridge. The name change happened some time after the toy store closed. The new shop left some Lego figures in the first floor windows, again by popular demand.

Related articles

- Old maps of Venice

- A Venetian Law

- Prostitution in Venice

- Fornicators of Nuns

- The Republic of Venice

- State institutions of the Republic of Venice

- Chronology of major Venetian state institutions

Leave a Reply