The Black Plague was a recurrent scourge in the 1600s, and one of the common precautions in Venice was to quarantine persons suspected of carrying the contagion. That meant anybody who had been in close contact with a plague infected person or place.

Venetian Stories

This post is an issue of our newsletter — Venetian Stories — which goes out every few weeks, to keep in touch and share stories and titbits from and about Venice and its history.

Quarantining people and goods was one of the main purposes of the Venetian lazzaretti islands.

Over the three centuries the Venetian lazzaretti operated, tens of thousands of persons must have gone through quarantine on the two islands.

How did that work? How was it being locked up like that for a month or more, between tall walls, under armed guards, on a tiny lagoon island?

We know little about the experience from the point of view of the person in quarantine, but we have some other relevant documents.

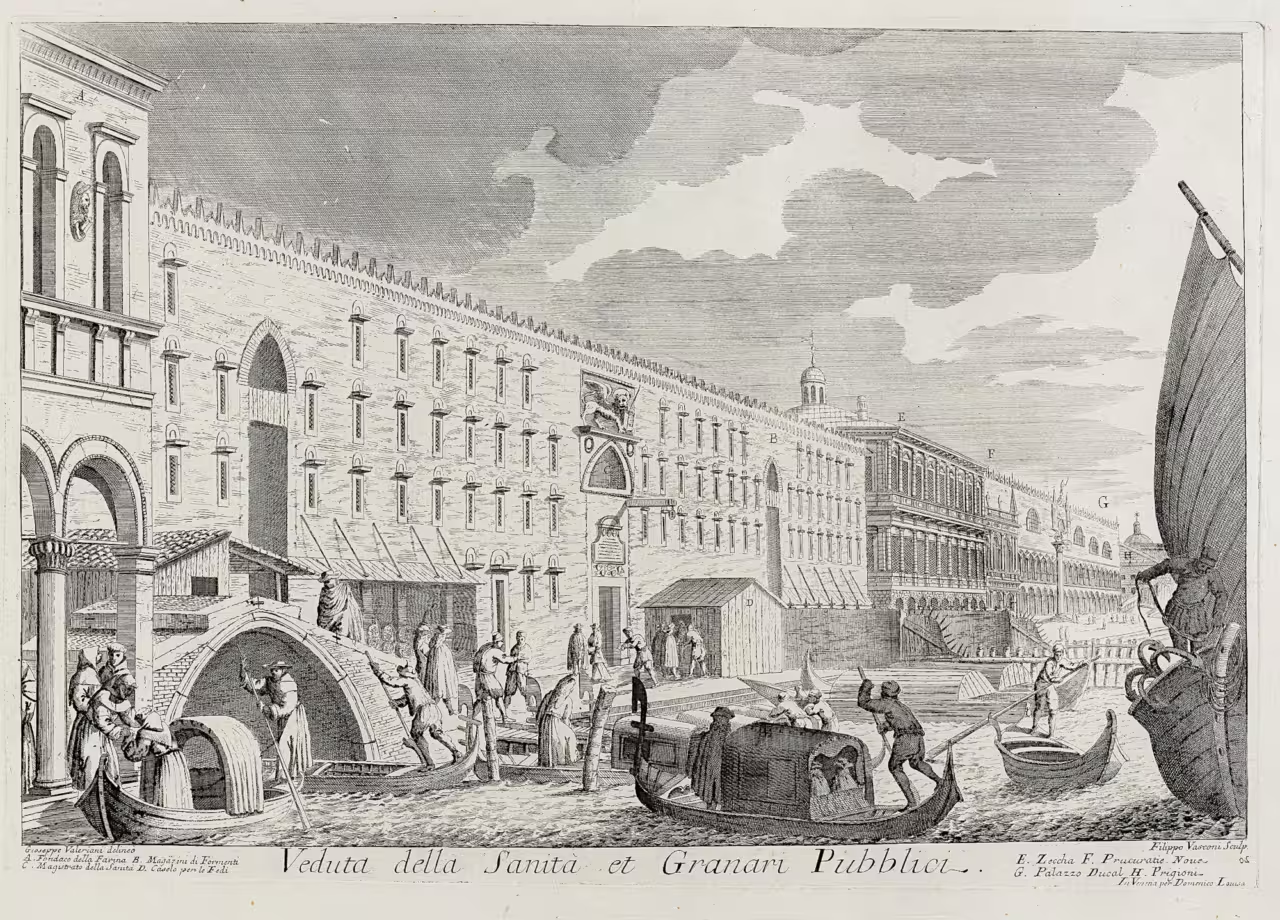

The Magistrato alla Sanità

The Magistrato alla Sanità was responsible for the running of the lazzaretti, since its inception in 1485 until the end of the Republic in 1797.

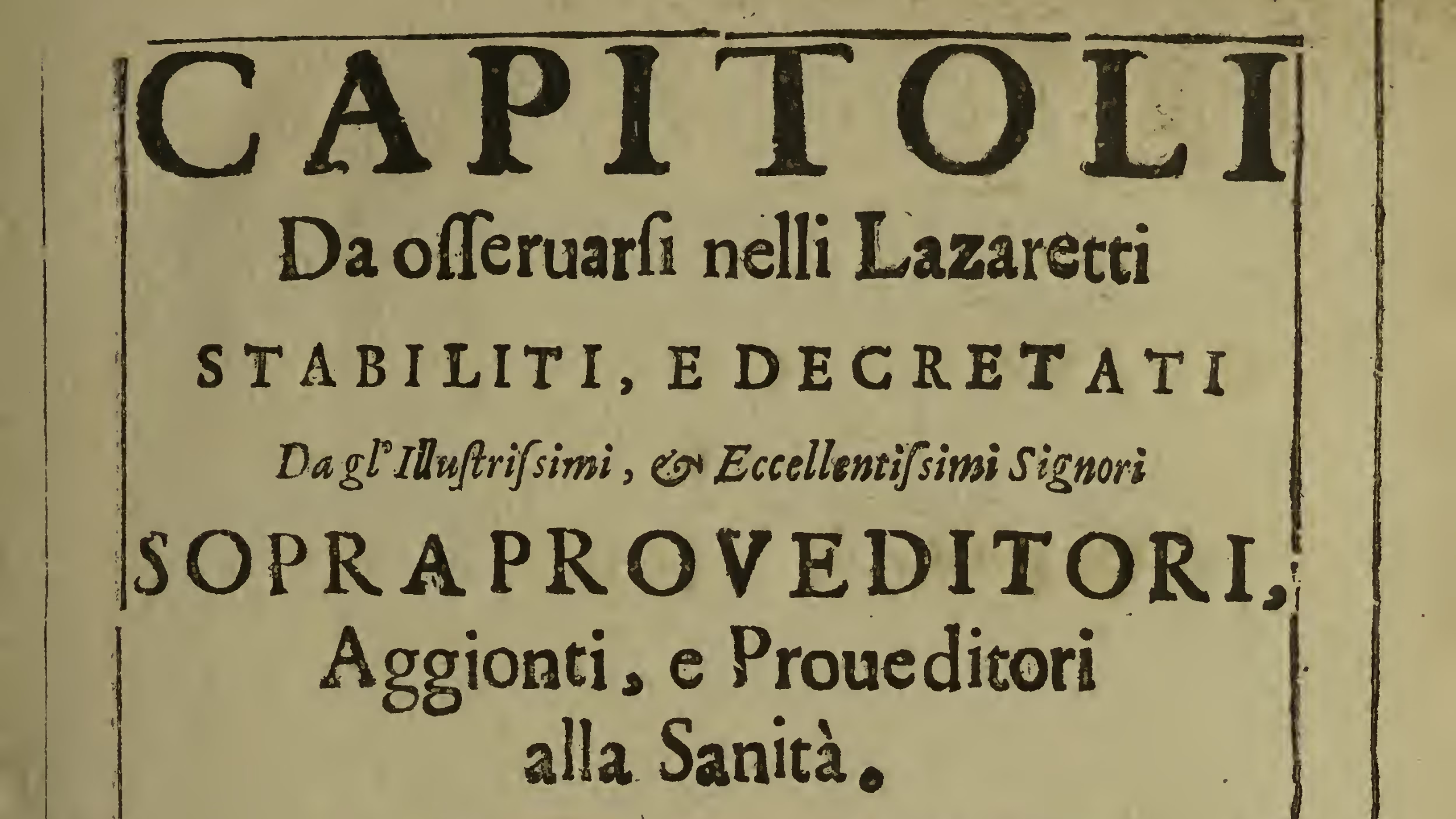

After the devastating epidemic of 1630-31, the Magistrato alla Sanità made a collection of instructions to the priore — the manager — of the lazzaretti, setting out his duties and responsibilities in detail.

The introduction to this forty page manual or instruction booklet is dated 1656, and I have found printed copies from 1674, 1719 and 1743. At the end of the booklet it states that the notary of the Magistrate has to give a copy to each priore when appointed, and get a signed receipt.

The expectations of the Magistrato alla Salute of the prior of the lazzaretti tell us something about how quarantine in the lazzaretti in the 1600s and 1700s worked.

Lazzaretto Nuovo

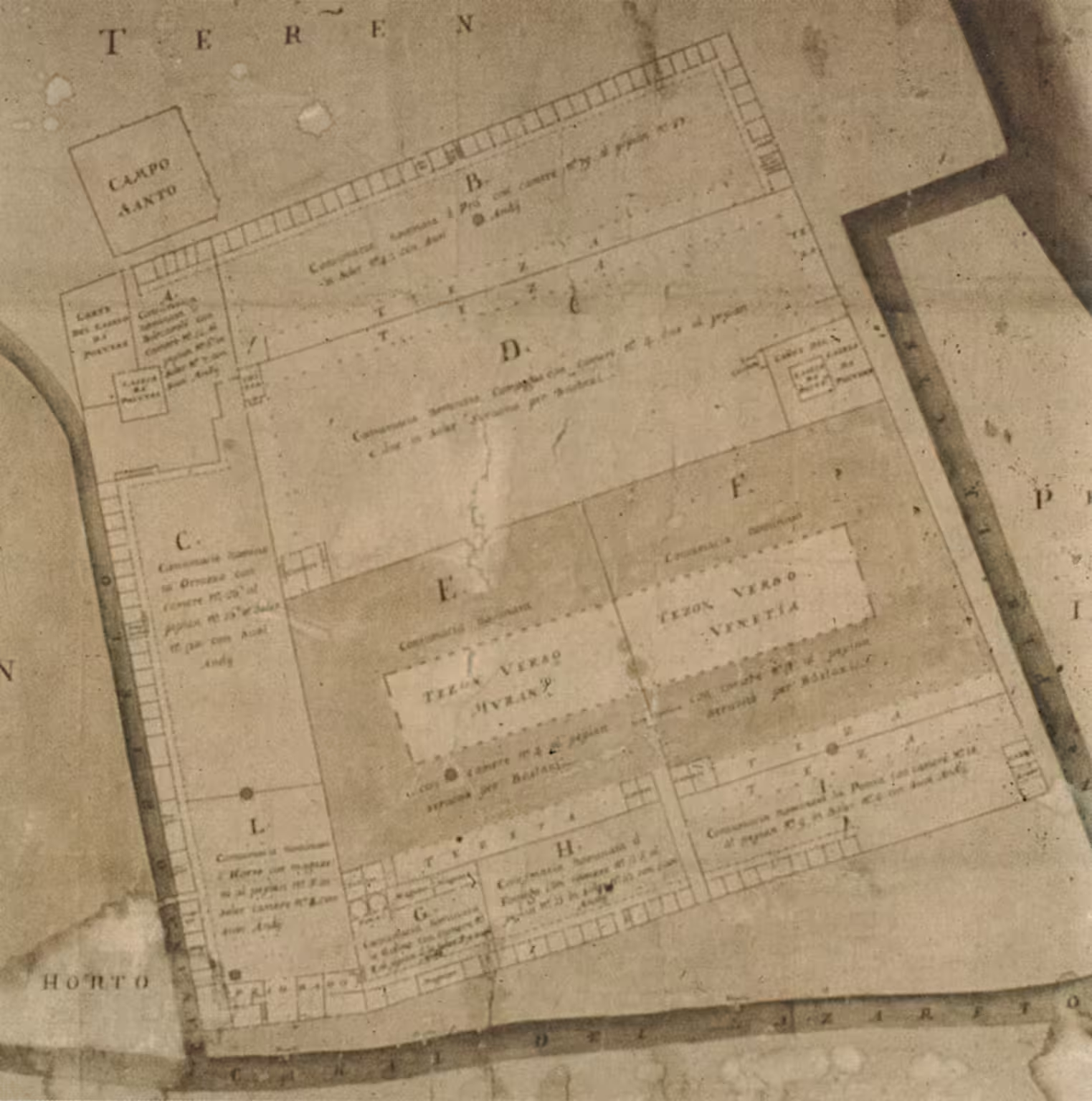

To understand the rules set out by the Magistrato alla Sanità, we need to have an idea of the physical setting the quarantine took place it.

The main quarantine island was the Lazzaretto Nuovo, which fortunately has been studied quite well.

The Lazzaretto Nuovo had a tall surrounding wall, and from the outside it looked almost like a fortress, with very few windows and doorways, and lots of chimneys.

Internal walls subdivided the entire enclosure into about a dozen separate compartments, called contumacie. Some were for the quarantining and treatment of goods and merchandise, but most were for people.

Every contumacia had one access door, from the fondamenta outside. There was not internal communication.

The contumacia for people had a varying number of rooms, on two storeys, along the outside wall. The rooms weren’t very large, just enough for one or two beds and a fireplace. Accommodation would not have been luxurious, but it probably wasn’t worse than on the ships most persons arrived on.

Each contumacia had access to a cistern for water, and there was a corner somewhere where people could relieve themselves. There were also a number of teze — half-roofs — which gave some cover for the sun or rain without being real buildings.

The ground within each contumacia was in part paved in brick, in part dirt.

Staff at the Lazzaretto

The responsible manager for a lazzaretto was the priore. The booklet mentioned earlier was a kind of instruction manual for each newly appointed priore.

Each contumacia was overseen by an armed guardian, assigned to the contumacia for a single quarantine cycle. The Magistrato alla Sanità appointed the guardians directly, since they were the daily enforcers of the safety procedures in the lazzaretti. However, the guardians answered to the priore in the day to day business of the lazzaretto. They were paid by the people in quarantine.

There were other people at the lazzaretti, but they were mostly working with the quarantining and cleansing of merchandise and goods.

Contumacia — Quarantine

People ended in contumacia — quarantine — because they were suspect. This meant that they had been in contact with somebody infected with the plague, or something suspected of carrying the contagion, or they had been in some place perceived to be contagious.

We have some clear and scientific ideas about the cause of illness and how contagion works, but in the 1600s and 1700s that knowledge didn’t exist yet. The rather vague ideas were that bad air would get you sick, and that somehow persons, animals and things could transmit the contagion.

NB: All page references are to the 1674 edition of the Capitoli Da osservarsi nelli Lazaretti Stabiliti, e decretati Dagl’Illustrissimi, & Eccellentissimi Signori Sopraproveditori, Aggionti, e Proveditori alla Sanità. See full transcription and links here.

Entry

At arrival to the lazzaretto the priore kept a record of all individuals and objects entering the lazzaretto (p. 16).

Personal items

People obviously travelled with various personal items, which they brought, or tried to bring, with them into contumacia.

The priore was not allowed to take anything from anybody in any way whatsoever (p. 8), and all personal items had to be registered at arrival so they could be returned afterwards (p. 16-17).

However, the priore could remove any items which were not for personal use, to the quarantine areas for goods and merchandise, again meticulously recording all such removals (p. 19).

All arms of any kind whatsoever had to be confiscated indifferently and kept in a safe place, with a receipt given to the owner, so they could be returned after the quarantine period (p. 19).

Food

Apparently it was not uncommon to travel with live animals, both for company and for food, because there are provisions that all animals such as cats and dogs, no matter to whom they belong, must be kept tied up or in cages. In the case of poultry in the contumacie, the priore had to ensure the wings were clipped (p. 13).

Food arrived through authorised food sellers on boats.

No food seller was allowed to approach the islands without a permit of the magistrate. Furthermore, the food sellers couldn’t leave their boats, but had to remain on their boats and move from the door of one contumacia to the next that way.

The priore had to be present, and enforce the rules together with the guardians of each contumacia.

Food sellers should come to the islands twice daily to sell the people in quarantine the necessities, but they were forbidden from selling sprits and tobacco. Their prices should be reasonable, and the quality good (which probably meant that often they were neither).

The practicalities of the transactions were by means of a basket on a stick, which had to be at least 3-4 arm lengths. The seller placed the food in the basket, and using the stick handed it to the people on the fondamenta of the lazzaretto. The payment went the other way, but before the money was placed in the basket, the priore had to ensure that the coins had been immersed in salt water or vinegar.

The priore and the guardian of the contumacia had to ensure that nothing else went into the basket and every irregularity had to be communicated to the magistrato immediately (p. 23-24).

Guests

No visits were allowed if not with a written permit from the magistrato.

Visitors couldn’t leave the boats, and the priore and guardian of the contumacia had to be present, for the importantissimi concerns for public health.

Only the persons explicitly mentioned in the permit were allowed to speak.

No objects of any kind could be passed between the visitor and the person in quarantine, without express permit from the magistrato with the signature of at least two Signori, and the objects had to be cleansed first (p. 24)

Whoever wanted to bring items or food stuffs to a person in quarantine, could, without permit, bring them to the prior, who was duty bound to receive them and pass them on to the beneficiary. No direct contact with persons in quarantine was permitted (p. 25).

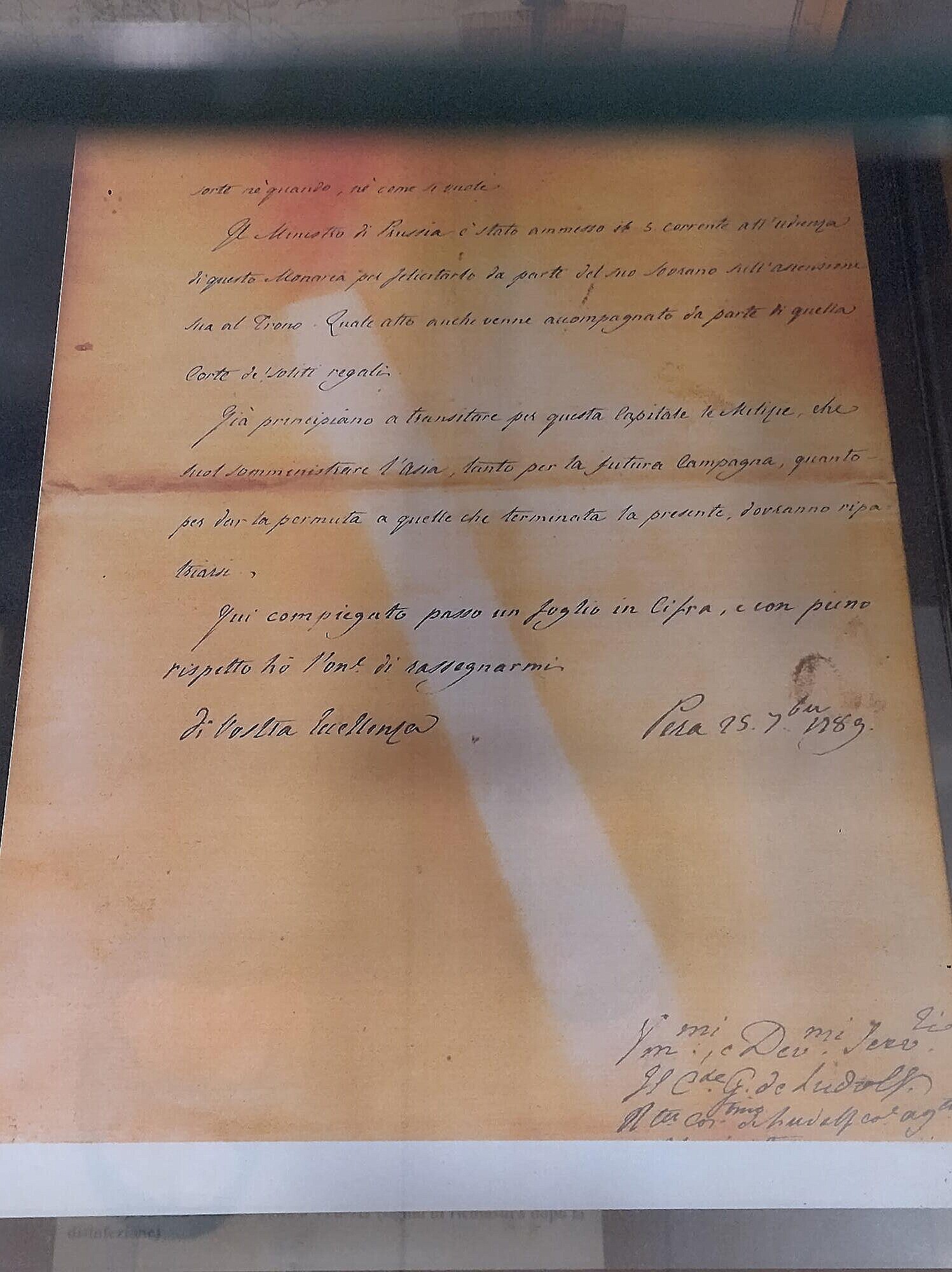

Letters

Letters and health certificates had to be perfumed, sheet by sheet, and passed to the prior on a stick. He would then place them under seal under the eyes of the interested parties, before sending them to the magistrato.

Whatever letters passengers had with them from aboard, had to be given to the prior before entering quarantine. He should perfume them for a day, and send them to the magistrate for further processing (p. 25).

The idea of ‘perfuming’ letters probably meant fumigation, because contagion and sickness was caused by bad air.

Leisure & play

People weren’t expected to have fun.

The priore was charged with keeping people quiet, and prevent all scandalous behaviour. Dancing, ball games or other entertainment which could offend or limit the efficacy of the contumacia were all forbidden (p. 17).

Specifically the priore had to ensure that the guardians didn’t run side businesses like bars, gambling or any other affairs in the lazzaretti (p. 18).

If the magistrato forbade all this, it is probably because it happened.

Sickness

Naturally issues of sickness and death were important concerns in a quarantine station for bubonic plague.

Anybody sick within a contumacia with suspicion of mala contaggiosa, had to be isolated as much as possible from the others within the contumacia, immediately, to avoid the spread of the disease (p. 17).

Any cases of sickness had to be communicated to the magistrato. If people got worse, a confession would be organised by the magistrato on an ad-hoc basis with proper provisions for public health (p. 20).

Testaments

Coerced testaments was a well-known problem within the lazzaretti, and the booklet has several pages covering the correct way to handle the writing of testaments in the lazzaretti.

Testaments should be written in a book of testaments by the chaplain with five witnesses of the most respectable people in the contumacia. They have to be present during the entire dictate. Literate witnesses had to sign the testament in their own hand, name and surname clearly readable.

If a chaplain couldn’t be procured, the priore had to write the testament in the same way, and if the priore wasn’t available, any other person on the payroll of the lazzaretto.

Neither the chaplain nor the priore, nor anybody else on the payroll of the lazzaretto could be executors or beneficiaries of testaments written in the lazzaretti.

The book of testaments had to be kept faithfully, and passed on the successor with a receipt, so the whereabouts of the book could always be established.

If anybody wanted a public notary to write the testament, the magistrato had to be informed, but their preference was for the chaplain or the priore to do the job.

They received a fixed payment, determined by the magistrato, for their work, and they were not allowed to receive anything else from anybody for the same task (pp. 20-21)

Deaths

In the case of deaths in the lazzaretti the priore had to inform the magistrato immediately. Nobody could bury or touch the body, until the doctor of the magistrato has seen it. With the doctors permit, the prior could see to the burial in the burial ground of the contumacia. No shrouds of any kind were permitted. The burial should be dug by people from the same contumacia, deep two arm-lengths or more if possible. If the cadaver was infected, it had to be covered by a layer of caustic lime and as much earth as possible.

The prior then had to make an inventory of the belongings, objects, money, anything, of the deceased, in the presence of the guardian of the contumacia and two or three witnesses from the people in quarantine. Nothing could be disposed of without the written permit of the magistrato (p. 22).

General safety precautions

People were locked up, and they had to see to the proper treatment of their own belongings.

The magistrato imposed that only the priore had the keys to the doors of the contumacie. All doors to the contumacie were to be locked from evening prayer until dawn, but generally the doors could only be unlocked for the purpose of the quarantine (p. 13).

The guardians had to ensure that all objects used by the passengers were hung on lines for airing daily, to combat contagion (remember bad air). The priore had to visit each contumacia twice daily, in the morning and after lunch, to ensure everything was done according to the rules and procedures of the magistrato (p. 19).

Business dealings

No commercial agents could visit people in quarantine, not even with a mandato — permit. If they showed up anyway with a permit, the priore had to confiscate it and send to the magistrato (p. 17).

Clearly there had been cases of such agents showing up with fake permits, to get goods and business moving in spite of the public health precautions.

Financial obligations

The only financial obligation of the people in quarantine was to pay the guardian for his services, at a daily rate set by the magistrato.

The booklet clearly states that the priore could not receive or take anything whatsoever from the people in contumacia. Their only obligation was towards the guardian (pp. 8-9).

Leaving

Nobody could leave the lazzaretti without the permit of the magistrato.

At departure fedi di sanità — health certificates — were issued, and they had to include the health status of the person at the time, and certify that clothes had been aired and handled correctly during the contumacia, and any kind of incidents during quarantine, such as malaria or deaths.

NB: Malaria doesn’t mean the illness malaria, but mal-aria — bad air — hence any contagious sickness whatsoever, caused by the exposure to bad air.

Before leaving people had to account for every piece of public property they had used during their contumacia, that nothing was burned or damaged, in which case they had pay compensation for the damages.

They also had to sweep and clean all the spaces where they had stayed, and take away and burn as well as possible all garbage.

Finally, nobody could leave before they have paid the guardians in full (pp. 25-26).

Notable omissions

In some respects the rules in the booklet are very precise and specific, but other things are conspicuously absent.

There are no provisions, at least in this document, about what would happen to those who for some reason couldn’t buy food from the food sellers.

Likewise, there are no provisions for firewood for heating or cooking. The rooms at the Lazzaretto Nuovo all had fireplaces, and the island was known to “look like a castle” because of the many chimneys. There were, however, provisions for an extra 10 ducats/year to the priore for his firewood needs.

Also, the booklet gives no indications of the expected length of the quarantine. It was left entirely up to the discretion of the proveditori and sopraproveditori of the Magistrato alla Sanità, which, given they issued the text, was probably convenient.

This meant that when people entered the lazzaretto, they had absolutely no idea about when they would be let out. Normally the quarantine was around thirty-forty-fifty days, around forty-ish, which is the meaning of the word ‘quarantine.’

Related articles

I have written extensively about the lazzaretti, because I work there part-time as guide. There are too many articles to list here, but the most important are these:

- Capitoli Da osservarsi nelli Lazaretti — 1674

- Lazzaretto Nuovo – the Plague island

- Lazzaretto Vecchio

- A Chronology of the Black Plague in Venice

Bibliography

Magistrato alla Sanità. Capitoli Da osservarsi nelli Lazaretti Stabiliti, e decretati Dagl’Illustrissimi, & Eccellentissimi Signori Sopraproveditori, Aggionti, e Proveditori alla Sanità. Venezia, 1674.

Leave a Reply