The lazzaretti were a central part of the Venetian republic’s response to the emergency of the bubonic plague, which devastated Venice and much of Europe in the late 1300s and early 1400s.

Venice was the first European state to take an organised proactive stance against the threat of the black plague. From the early 1400s, they systematically isolated the sick, and later also people and merchandise that had been in contact with the sick.

It is no coincidence that two Venetian words related to the plague have made it into common usage over the world as a result of this: lazaret and quarantine.

The arrival of the Plague

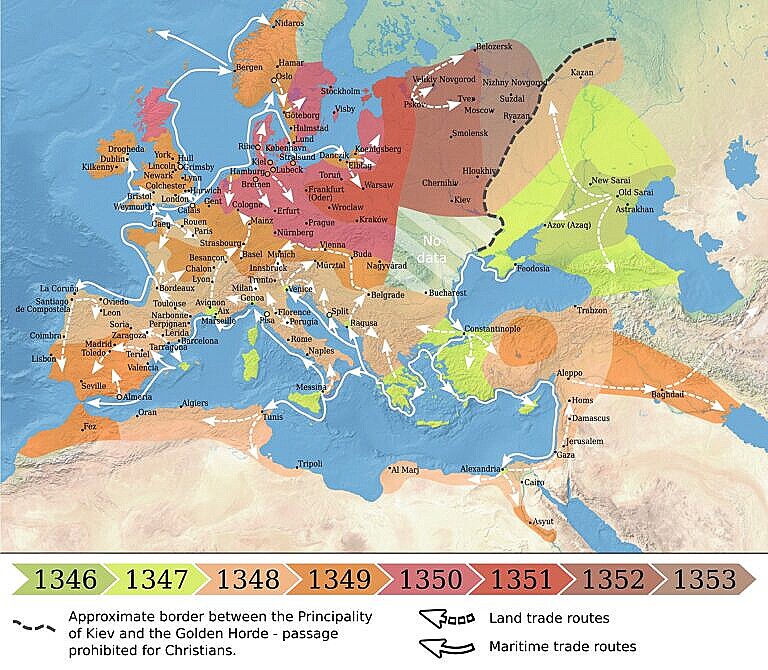

In late 1347 or early 1348, the black plague came to Venice on a ship. The decease soon spread, and people died in their tens of thousands.

The plague returned in 1361, 1371, 1374, 1390, 1400, 1423 and 1439 just to mention some of the years.

The effect of the plague on the city was devastating. At least one in three Venetians died a horrific death, for apparently no reason, and anybody who had been in contact with the sick were likely to fall ill as well.

Fear and terror reigned.

The plague left the survivors deeply traumatised, and the socio-economic fabric of the city in shreds. One shop was closed because the owner was dead, another because the workers were missing, yet another were without clients, and others again without suppliers.

It took a long time to recover, repopulate the city and revive the economy, just for yet another wave of the plague to arrive.

- The Black Plague

- A Chronology of the Black Plague in Venice

- Bad air will get you sick

- Why did it take so long?

- The plague doctor

Lazzaretto Vecchio – the hospital

In 1423, the Senate of the Serenissima finally decided to do something proactive to keep the inevitable return of the plague away from the densely populated city.

They established a hospital on an island in the lagoon south of Venice, which became the first of the Venetian Lazzaretti (later called Lazzaretto Vecchio).

The word lazzaretto comes from this island. It was occupied by a monastery, dedicated to St. Mary of Nazareth – Santa Maria di Nazaret. The last word became Nazaretum, and maybe influenced by a nearby island dedicated to St. Lazarus it became Lazzaretto.

Henceforth, anybody suspected of having the plague, either in the city of Venice or on arrival in the city, went to the Lazzaretto and stayed there until they either died or survived. Mass graves on the island awaited the unfortunate victims.

A special plague doctor inspected all ships arriving in Venice, and sent anybody found to be sick directly to the Lazzaretto Vecchio, before the ship could proceed to the harbour.

This got the obviously sick people out of the way, but over time the Venetians found out that this was not enough to keep the city safe.

They discovered that the plague could spread through persons who, while apparently healthy, had been in contact with the sick. They also understood that objects could carry the contagion.

- Lazzaretto Vecchio

- A Chronology of Lazzaretto Vecchio

- Open day at the Lazzaretto Vecchio

- Lazzaretto Vecchio – six centuries

- Six hundred years of Lazzaretto Vecchio

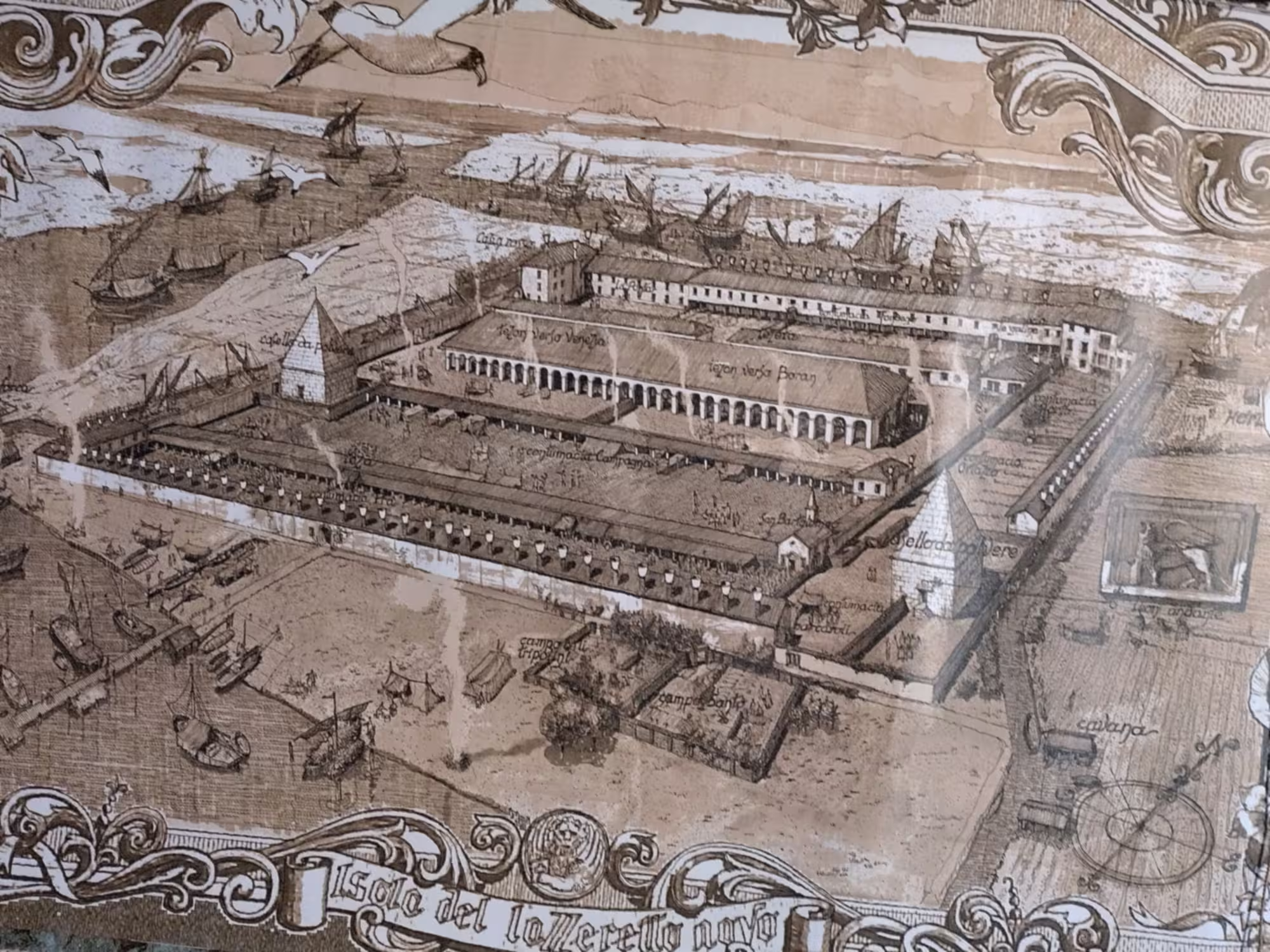

Lazzaretto Nuovo – the quarantine station

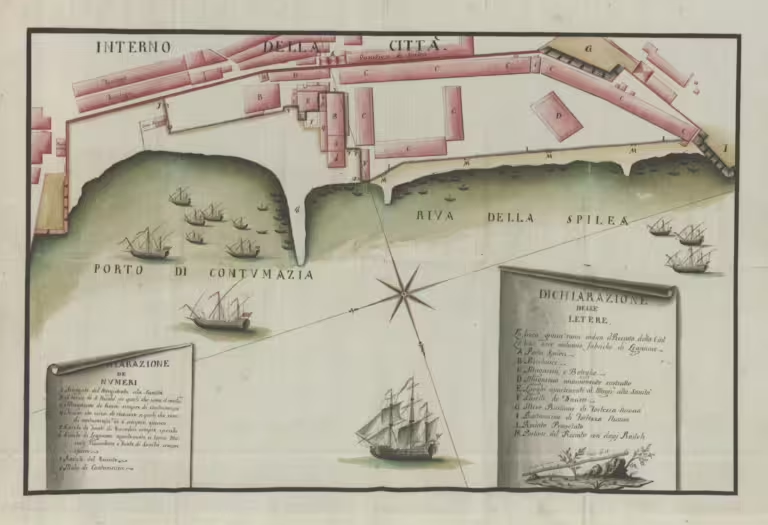

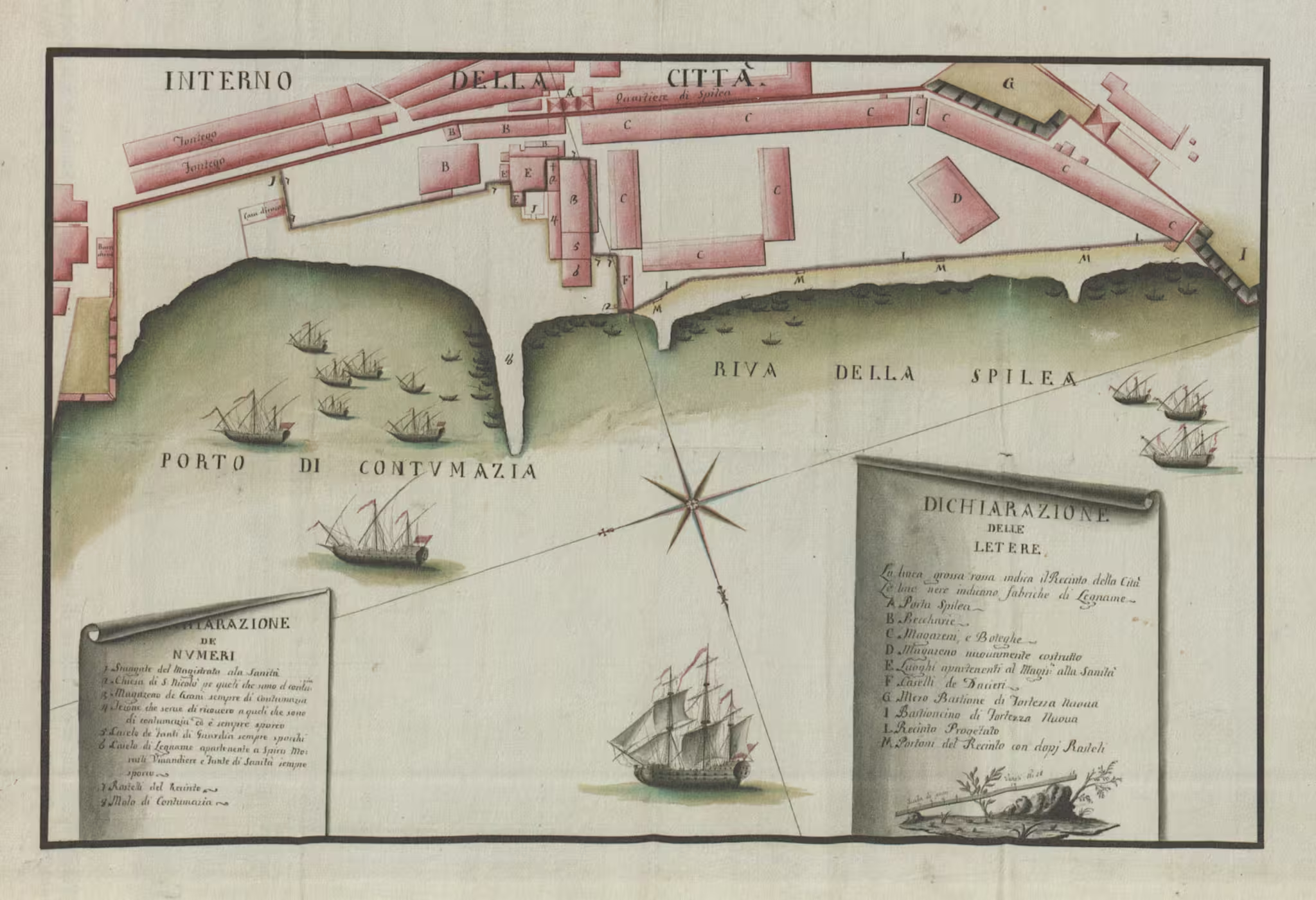

The solution was to create a dedicated quarantine and disinfection station.

The Serenissima took over another island in 1468 for this purpose.

This island, then called the Vigna Muradlia, a walled vineyard, was the property of the Benedictine monks of San Giorgio Maggiore. It became the Lazzaretto Nuovo.

The Lazzaretto Nuovo is in the northern lagoon, strategically placed close to the entrance to the lagoon, the bocca di porto, at San Nicolò. Therefore, whenever the plague doctor found an infected ship, the sick would go to Lazzaretto Vecchio as before, but the ship, the cargo and the crew together with eventual travellers would now go to Lazzaretto Nuovo for a period of quarantine, and for the cargo, cleaning.

The quarantine station on Lazzaretto Nuovo expanded over the next century, and had at its largest over one hundred rooms with two hundred beds for sailors and travellers, and several large buildings for the cleansing of the merchandise from the ships.

- Lazzaretto Nuovo – the first quarantine station

- A Chronology of the Lazzaretto Nuovo

- Antonio Moro and the Somachio

A great success – lazzaretti all over

The lazzaretti, and the procedures the Venetians developed around them, were a success.

In the three centuries the two lazzaretti were operational, the plague got into Venice city only twice — in 1575-77 and 1630-31 — and in both cases it arrived from the mainland, and not from the sea by ship.

The system the Venetians had created worked, and worked well.

Consequently, many other cities copied the idea and built their own lazzaretti. Nearby Italian cities like Verona, Milan and Ancona soon had lazzaretti, and then in Genoa, Marseilles, and Barcelona.

The Venetian themselves started creating lazzaretti further down the trade routes towards Greece, to intercept the infected ships before they arrived in the lagoon. These lazzaretti were often temporary structures, put up when needed, and taken down afterwards.

In other places, like on the Venetian Corfu, a dedicated part of the harbour became the quarantine area. In such cases, the sailors and travellers did their quarantine directly on the ship.

The end of the lazzaretti

The Black Plague subsided throughout the 1700s, and and the end of the century the two Venetian lazzaretti ran almost empty.

With the reduced risk, they were too large for the needs of the time, and therefore not economical. Furthermore, Venice hadn’t had a major outbreak of the plague since the 1630s, thanks to the prevention carried out at the two lazzaretti.

Consequently, the Venetian Magistracy of Public Health drew up plans in the 1780s for the demolition of the lazzaretti.

Fortunately for us, it didn’t happen. Napoleon’s conquest of Venice meant the plans were either forgotten or ignored.

Lazzaretto Nuovissimo

The replacement of the two too large lazzaretti was the island of Poveglia in the southern lagoon. It became the Lazzaretto Nuovissimo.

Poveglia was better placed, as the larger ships of the 1700s entered the lagoon further south, where the bocca di porto was deeper. It was also already controlled by the republic, and therefore readily available.

There were very few cases of the black plague in the late 1700s. The records tell us that only eighteen died of the plague on the island in the years it was a lazzaretto. Of these, twelve died in the last major incident of bubonic place in 1793.

Bibliography

Busato, Davide and Paola Sfameni. Poveglia : l’isola alle origini di Venezia. 2018.

Fazzini, Gerolamo (ed.). Venezia : isola del Lazzaretto Nuovo in Guide archeologiche della Laguna di Venezia. Archeoclub Venezia, 2004.

Fazzini, Gerolamo (ed.). I Lazzaretti Veneziani : il sistema sanitario della Serenissima contro le epidemie. Marcianum Press, Venezia, 2024.

Vanzan Marchini, Nelli-Elena. Guardarsi da chi non si guarda : la Repubblica di Venezia e il controllo delle pandemie. Sommacampagna : Cierre, 2022.

Leave a Reply