The old Venetians, through their innovative system of lazzaretti, managed to stay mostly clear of the Black Plague for much of the 1500s, 1600s and 1700s.

Following the recurring waves of the plague from the mid-1300s onwards, the Serenissima found a way of keeping the plague out of the city. A system which included isolation of the sick, quarantine of those at risk, cleansing of the merchandise from infected ships, strict enforcement of health safety rules and an information gathering network spanning most of the Mediterranean kept Venice safe.

Focus was on prevention because the Venetians had learned early on that they had no cure for the plague. If you cannot cure a fatal disease, your only chance is to avoid getting it.

The Venetian system, centred on two lagoon islands called Lazzaretto Vecchio and Lazzaretto Nuovo, worked incredibly well. In fact, the plague only entered the city of Venice twice in the 350 years the two lazzaretti were operative, and on both occasions the contagion entered from the mainland. This is important because the Venetian system almost entirely focused on keeping a ship-borne contagion at bay.

Yersinia pestis

We know that a bacterium, Yersinia pestis, causes the Black Plague. It can enter the bloodstream through the airways or through insect bites.

One of the main reservoirs of the bacteria were in the blood of the omnipresent population of black rats, both in the cities and on the ships. Insects, such as fleas and mosquitoes, can easily carry the bacteria from one individual to another, whether human or not.

The plague can also spread through airborne micro particles. Pneumonic plague is almost always fatal, while the bubonic plague by an infection through insect bites kills 40-50% if untreated.

Being a bacterial infection, antibiotics can cure it.

We know all this, but it is modern science and modern technology. Before the late 1800s nobody knew about bacteria, and before the early 1900s there were no antibiotics.

Yet, without any of this knowledge, the Venetians created a well functioning preventive system with a very high success rate.

Miasma

It wasn’t all trial and error, even it that also had a role.

The Venetians, like many others at the time, believed in miasma.

Miasma (sing. miasmata) are invisible ‘things’ floating around in the air, which will get you sick if they enter your body. The idea is ancient, going back at least to Aristotle in the 300s BC.

People believed that the miasma generated in decomposing corpses and rotting rubbish, and more in general, in foul smelling places. I write ‘generate’ because people didn’t believe the miasma to be a reproducing living organism, but rather something that spontaneously appeared if the conditions were right.

If the miasma appears in foul smelling environments, how do you purify such a place? For starters, obviously, ventilation to remove the bad odours. Alternatively, by replacing the bad smells with something nicer, like perfumes, vinegar, tobacco smoke, incense or the fumes of burning herbs.

An interesting aside is that within the theory of miasma, there is no contagion. The disease doesn’t move from one individual to another by some kind of transmission. The spread of disease is an environmental problem because people get sick by exposure to miasma in a polluted environment. To prevent the disease, the environment must be purified.

Such beliefs, paired with other fears and superstitions, often led to a general perception of ‘bad air’ or even ‘night air’ being a health hazard.

The disease malaria is caused by a parasite transmitted by mosquitoes. The name is a testimony to the belief in foul air as the cause of disease. It is in fact mal’aria, from the Italian for bad air.

Even today, many such misconceptions linger. Plenty of people still believe you can ‘catch a cold’ by exposure to freezing air, when the common cold is actually a virus infection.

Ventilation and fumigation

For us, with our baggage of modern science and technology, the idea of miasma might sound ridiculous, but that is entirely on our arrogance. The people of the past weren’t stupid. They had to deal with existential problems like the plague without our scientific knowledge, and they very often did quite a good job. The main proof of that is that we’re here.

The Venetians created the procedures used in the lazzaretti partly from the concept of miasma, especially for cleansing the merchandise from infected ships.

Many of the procedures the Venetians applied in the lazzaretti actually worked, at least to some extent.

For example, the main building on the Lazzaretto Nuovo, called the Tezon Grando (the big warehouse) was a building with open arches all along the sides, so the wind could blow straight through. Ventilation served to keep the air inside clean and healthy for workers who had to do the dangerous job of washing and cleaning objects from infected ships.

Often they would make bonfires of juniper and rosemary just outside the building, and have the fumes waft through the inside of the building, again to purify the environment both to assist the cleansing of the merchandise and to keep the workers safe.

Did it work?

Yes, it did, at least partly.

The plague also spread through airborne particles, so ventilation would have an effect.

Cotton, silk and the resulting threads, fabrics and clothes were a substantial part of Venetian trade. The fleas, which are part of one way of transmission of the bacteria, can live in such goods. Fumigating the goods will cause the fleas to scamper.

A similar procedure of fumigation, applied to the empty ship, would cause the rats on board to flee. Consequently, the ship would be safer afterwards, which could be observed.

Likewise, treating metallic objects with vinegar will have a positive effect. Not because vinegar has a pleasant smell, but because it is a natural disinfectant.

This was, for example, how persons in quarantine on the Lazzaretto Nuovo could pay for better food or accommodation. They would drop their coins in a bowl full of vinegar, where the guards could then retrieve the coins.

As is evident from drawings from the Lazzaretto Nuovo, the guards had the necessary means to enforce proper social distancing.

Right result, but …

It is sometimes possible to get to a ‘correct’ result by a ‘wrong’ method.

The Venetians of the past departed from their perceived truth (the belief in miasma), drew some logical conclusions from that, acted accordingly, and observed that sometimes it had a positive effect. It is then only natural to feel confirmed that the point of departure, the belief in miasma as the cause of disease, is, in fact, correct.

Not everything conclusion drawn from faulty premises will be correct.

The archaeological digs on the Lazzaretto Nuovo have yielded a huge number of ancient pipes. Smoking tobacco offers some gratification on a biological level, but for believers in miasma it also offers protection from disease by purifying the air, not only for the smoker but also for those around them.

The belief in miasma persisted until the end of the 1800s, and it helped healthcare progress in many ways. Florence Nightingale, for example, used it to promote better hygiene in hospitals.

The idea helped the Republic of Venice protect itself against the plague.

Related articles

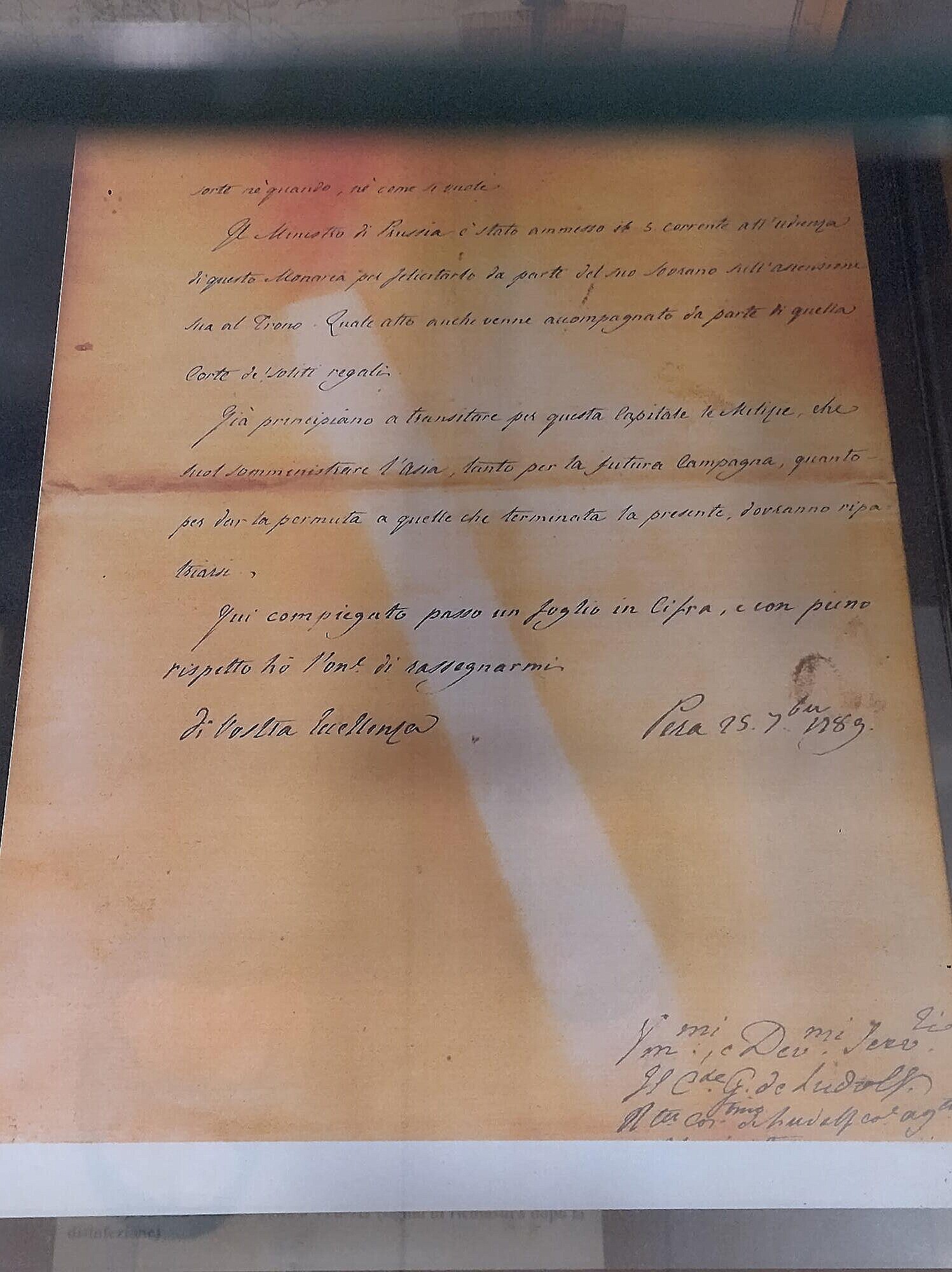

- Quarantine in the 1600s

- The Venetian Lazzaretti

- The Black Plague

- A Chronology of the Black Plague in Venice

- Capitoli Da osservarsi nelli Lazaretti — 1674

Bibliography

Fazzini, Gerolamo (ed.). Venezia : isola del Lazzaretto Nuovo in Guide archeologiche della Laguna di Venezia. Archeoclub Venezia, 2004.

Fazzini, Gerolamo (ed.). I Lazzaretti Veneziani : il sistema sanitario della Serenissima contro le epidemie. Marcianum Press, Venezia, 2024.

Magistrato alla Sanità. Capitoli Da osservarsi nelli Lazaretti Stabiliti, e decretati Dagl’Illustrissimi, & Eccellentissimi Signori Sopraproveditori, Aggionti, e Proveditori alla Sanità. Venezia, 1674.

Vanzan Marchini, Nelli-Elena. Guardarsi da chi non si guarda : la Repubblica di Venezia e il controllo delle pandemie. Sommacampagna : Cierre, 2022.

Leave a Reply