Here and there in Venice, you can find long, often convoluted, inscriptions. Sometimes they’re on a wall, sometimes on a freestanding stone. They’re not monuments to anybody. Some are ancient laws of the Republic of Venice, published on the streets and marketplaces, so nobody could claim ignorance of the law — because ignorantia legis non excusat.

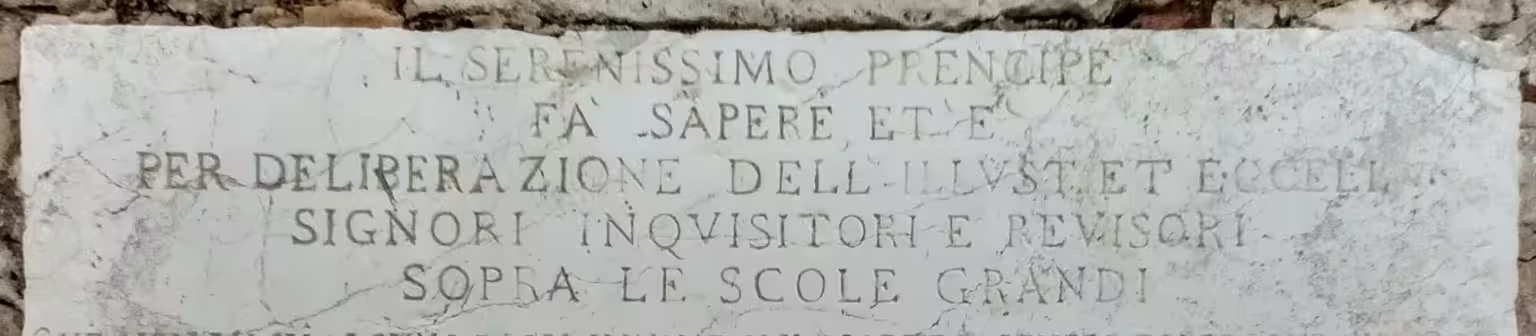

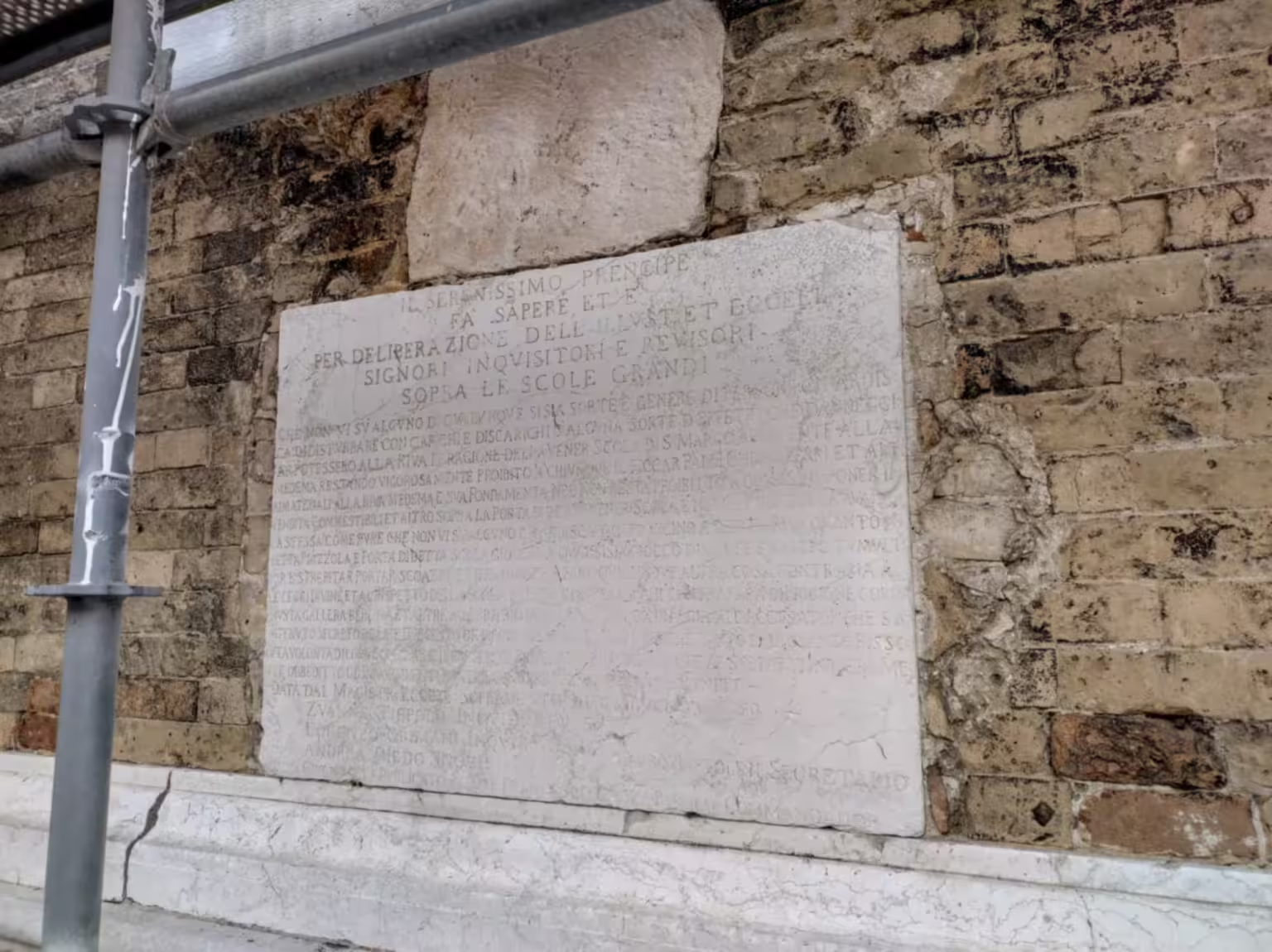

One such Venetian law inscription is mounted on the canal side wall of the Scuola Grande di San Marco, in Campo SS Giovanni e Paolo.

Checks and balances

The Republic of Venice didn’t have a legislative branch like most modern states have.

The general idea of dividing the powers of the state in separate executive, legislative and judicial branches is from the 1700s. The roots of the Venetian state are a thousand years earlier. The structure of the Republic of Venice was more or less settled in the Middle Ages.

In modern states the tripartite system is often one of checks and balances. The three branches of government controls and keep each other in check, ensuring no single institution becomes too powerful or steps out of its remit.

This is an idea the ancient Venetians would immediately recognise. They had checks and balances in their system, and it might very well be that the USA got the idea from Venice.

The checks and balances in the Venetian state were, however, implemented very differently.

The inscription in Venetian

Transcribed from the marble slab on the wall the text reads:

Il Serenissimo Principe

fa sapere et e’

per deliberazione dell’illust. et eccell.

signori inquisitori e revisori

sopra le scuole grandi

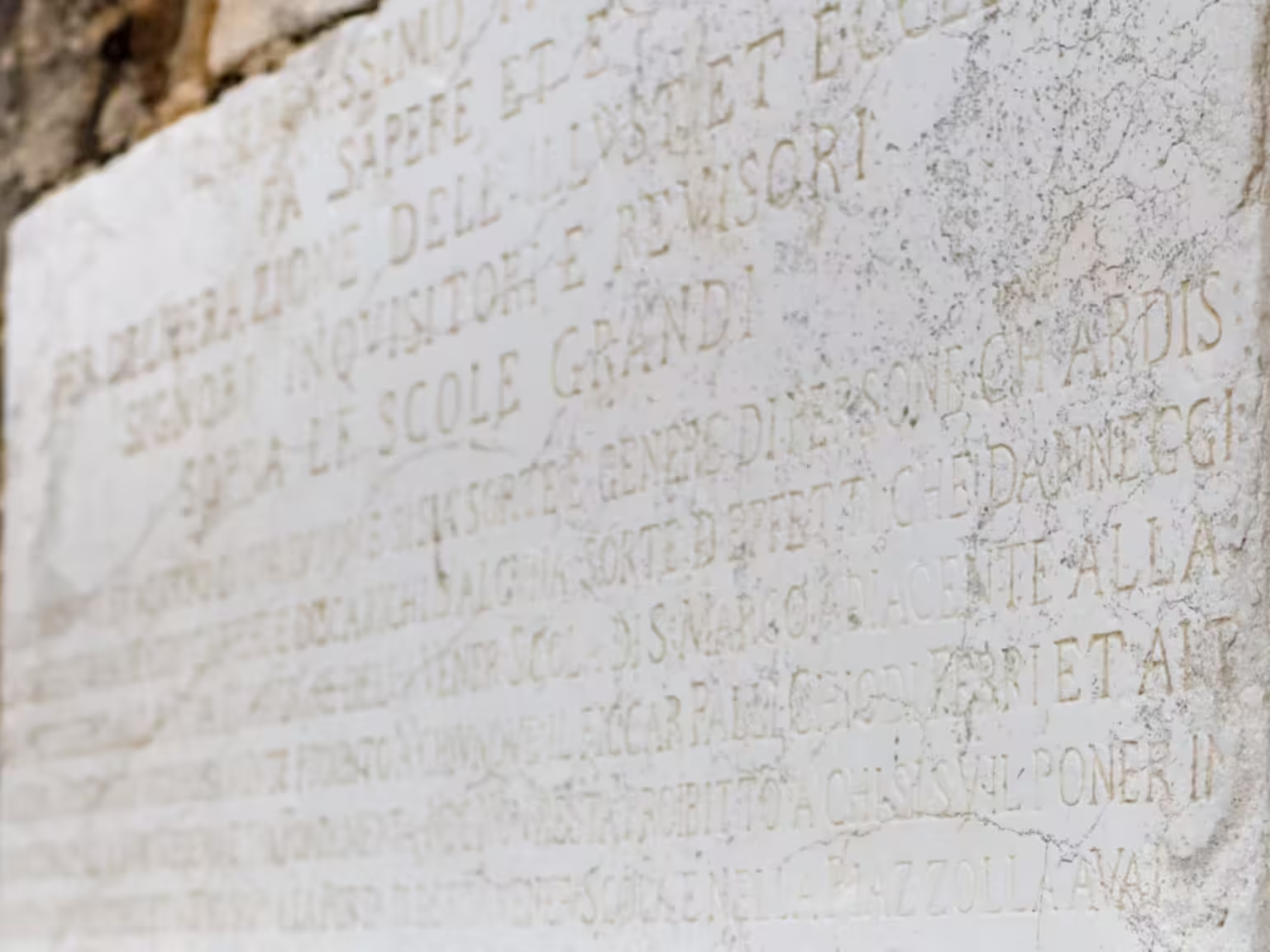

Che non vi sii alcuno di qualunque si sia sorte e genere di persone che ardisca di disturbare con cariche e discariche di alcuna sorte d’effetti che danneggiar potessero alla Riva di ragione della Vener Scola di S. Marco adiacente alla medema restando vigorosamente proibito a chiunque il ficcar palli chiodi ferri et altri materiali alla riva medema e sua Fondamenta Nec Non resta proibitto a chi si sii il poner in vendita commestibili et altro sopra la Porta di detta Vener Scola e nella Piazzola avanti la stessa come pure che non vi sii alcuno che ardisca tanto vicino a detta Riva quanto detta Piazzola e Porta di detta Scola gioccar a qualsisia gioco di carte et altro tumultar e strepitar porta scoazza et immondizie e fare qualunque altra cosa contraria alle Leggi Divini et al rispetto della scola stessa con Pena a chi contrafarà di Prigione corda frusta gallera berlina et altre ad arbitrio della Giustizia con Talgia all’Accusator che sarà tenuto Secreto de lire duecento de piccoli de Beni del Reo e perché tanto è Pia quanto Rissoluta volontà di loro Eccellze che il Presente Proclama resti in tutte le sue parti interamente obbeditto Gl’Innobedienti resteranno irremissibilmente e Puniti ~

Data dal Magistrto Eccellmo Sopradetto dì 8 Giugno 1759 ~

Zuane Tiepolo Inquis.Revis.

Lorenzo Grimani Inquis.Revis.

Andrea Diedo Inquis.Revis.

Lauro Bartolini Segretario

Dì 22 Giugno 1759 Publicato per me Francesco Lanza Publico Commandador

There’s a fair bit to unpack.

The introduction

The first part of the text is in my translation:

The Most Serene Prince

let be known and it is

by deliberation of the Illustrious and Excellent

Lords Inquisitors and Accountants

of the Great Schools

This is all about authority. It is visually distinct from the bulk of the text, and set in larger type.

The Serenissimo Principe is the Doge — the head of state in the Venetian Republic and the highest authority after the Consiglio Maggiore.

However, he’s just endorsing what others have decided. He is lending his authority to what follows.

The deliberators of the law in questions are the Illustri et Eccelenti Signori Inquisitori e Revisori sopra le Scuole Grandi. These are great men of ancient noble families, and they need titles that sound of something.

The office of the Inquisitors of the Great Schools, with three patrician Inquisitors, was instituted in 1622 by the Council of Ten.1

What they were responsible for was important, but a bit more mundane. They inquired into the accounts of the Scuole Grandi.

They were auditors.

Schools and Great Schools

The scuole in Venice were not educational institutions. The Venetians used the Latin word schŏla for guilds, confraternities and charities of different kinds. The Venetian use of the word might be related to the use in the English expression ‘a school of fish,’ in the sense that it represents a group that act and move as one.

The Scuole Grandi — the Great Schools — were a group of extremely wealthy Venetian charities. Over the centuries they acquired enormous wealth, and their symbols are still on the walls all over the city where they owned properties. The buildings still dominate the city, as the Scuola Grande di San Marco is a good example of.

The wealth of these charities didn’t belong to any specific individuals, just like the wealth of modern foundations. However, somebody had to manage it, and they might be tempted to use that position for personal gain — economically, politically or otherwise.

Consequently, the Venetian state established an office of auditors to make sure that the wealth of the Scuole Grandi went to charity according to statute, and not to benefit the administrators of the school.

The main text

The entire middle part of the inscription is almost one long phrase, so I’m going to translate it all, and discuss it afterwards.

That there may not be any whatsoever sort or kind of person who dares to disturb with loading or unloading of any kind of objects that could damage the quay belonging to the Venerable School of St Mark, it remains vigorously prohibited for anybody to fix posts or iron nails or other materials to the quay-side itself and its foundation, also it remains prohibited for anybody whatsoever putting up for sale comestibles and other in front of the gate of the said Venerable School and in the small square in front of the same, equally that there may not be anybody who dares very close to the said quay and small square and gate of said school to play at any kind of card games or other tumult or racket, bring garbage and refuse and do anything whatsoever contrary to the Divine Laws and the respect of the School itself with a penalty for who infringes of prison rope whip galley stock and other at the arbitration of Justice with a cut to the accuser which will be secret, of two hundred lire of the small of the crime and because the will of their Excellences is as pious as resolute, may the present proclamation remain in all its parts wholly obeyed. Who disobeys will remain unforgiven and punished ~

In all this bureaucratese, there are some hidden gems.

Firstly, the riva (the quay-side) and the fondamenta (the side-walk) are both the property of the school. That is the reason why the auditors of the Great Schools have the authority to make rules for the area.

Loading and unloading

Secondly, the riva and the fondamenta were for loading and unloading goods, and probably mostly ‘comestibles’ — food. Most of the campi — the squares in the city — had marketplaces for daily necessities like food and firewood.

Venice has no countryside and no nearby forests, so food and firewood had to come from the outside, by boat. Such activities were as regulated then as they are now, so somebody cannot just show up with a boatload of apples, moor somewhere and put on a table on the fondamenta to sell the apples.

The riva and fondamenta alongside the school were for loading and unloading goods for the market on the nearby campo.

That it was strictly for transit is clear from the ban on ficcar palli chiodi ferri et altri materiali — place posts, iron nails or other materials. Posts for mooring the transport boats, and iron nails on the quay-side for the same purpose. This is in effect a ban on leaving the boat unattended — or in modern terms: No Parking!

So, come in with your boat, unload the goods, and leave, so others can do the same.

The goods will have to go to the market on the campo. The text clearly bans the sale of food stuffs on the fondamenta. The fondamenta is, just as the riva, for transit, the movement of goods, and nobody should block the passage.

Disorderly conduct

Thirdly, we have rules about general conduct. No gambling, no littering, no making a racket, nothing against the ‘Divine Laws.’

Naturally, little of that would happen during the day, when the area was busy with people moving goods and things to and from the market in the campo.

These rules are probably intended for after dark, and after dark in ancient Venice was generally very dark.

There was little to no public illumination, so crime was rampant at times. Lighting insides used candles and oil lamps, but there were shutters on the windows, so very little light would come from the houses. Venetian alleyways were very dark at night.

Gambling was a popular pass-time in Venice as elsewhere, and there was little to stop somebody from putting up a table with a lamp in a deserted fondamenta after dark, and run a little hustle there.

Some would win at the table, others would lose, not all would pay their debts, and fights would ensue. The local prostitutes would hang around at the edge of the light from the lamp, to see if they could pick off a bit of the lucky guys’ winnings. That is probably what the euphemism about the ‘Divine Laws’ means.

Punishment

What will happen to those who break the rules? The text doesn’t give a lot of detail, but simply lists some possible punishments, and it is quite a list.

The possible punishments include: prigione corda frusta gallera berlina et altre ad arbitrio della Giustizia. Prigione — prison — means loss of person freedom, just like today, though substantially harsher. Corda — rope — refers to a kind of torture. Frusta — the whip — flogging. Gallera — the galleys — forced labour in the navy shipyards. In earlier times, that would have included rowing the war galleys. However, they were in disuse in the 1700s, so it means slave labour in general. Berlina — the stock — hence public ridicule. Finally, e altre ad arbitro delle Giustizia — other at the discretion of Justice — whatever that can be.

That is quite a wide range of possible sanctions for rule breakers. Supposedly, you wouldn’t be tortured for littering, but there’s nothing in the text to rule it out.

Law enforcement

Ancient Venice didn’t have a police force as we know it. The first ‘modern’ police force was the London Metropolitan Police from the 1820s, so there were no Venetian policemen prowling the alleyways looking for criminals. There was nowhere you could go a report a crime.

Each sestiere had some night watchmen, but that was about it.

The authorities relied on informants for control, which is explicit in this text: con Talgia all’Accusator che sarà tenuto Secreto de lire duecento de piccoli de Beni del Reo — with a cut (reward) for the accuser who shall remain secret, of two hundred ‘small’ lire2 of ‘of the goods of the crime.’

Basically, the state wanted people to snitch on each other, but it didn’t want it to cost anything, so the money came from sequestered goods from the people caught red-handed.

Also, the identity of the informant will remain secret, to avoid retaliation and revenge. Nobody will come forward with information to the authorities if they know that everybody will know who snitched. They would, probably justified, fear meeting the point of a knife in a dark alleyway sometimes later.

For the state having stopped one crime just for it to lead to another, possibly worse, crime makes little sense. Consequently, there’s no incentive on either part to break the secrecy.

We mean it!

The bit about the piousness and determinedness of the inquisitors and accountants, is basically a “we mean business” message.

That it needed saying tells us that many such rules often weren’t obeyed. There might have been some chips in the authority of the authorities here, if they need to emphasize their resolution.

Signing off

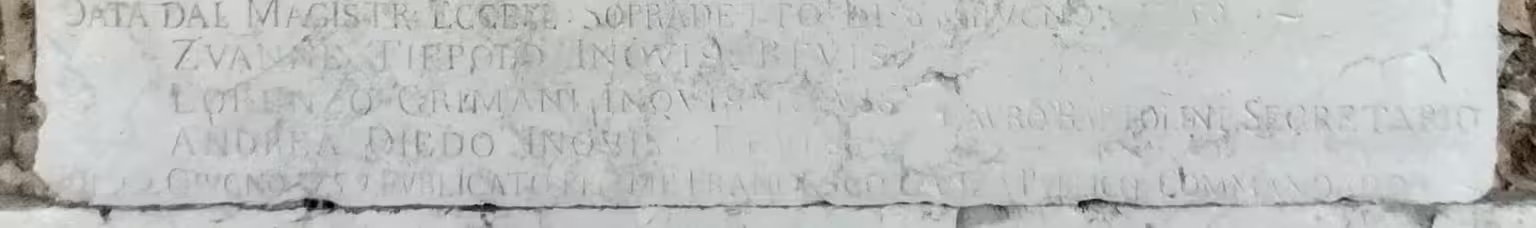

The end of the text contains some formalities.

Firstly, we have the date of the proclamation, on June 8th,1759.

The auditors

There are several names at the end of the text, of which three are grouped together: Zuane Tiepolo (Giovanni in Venetian), Lorenzo Grimani and Andrea Diedo.

These are not names of individuals I have found elsewhere, but that doesn’t mean they were nobodies. Their family names are very well known in Venice, as they were some of the most ancient families of the Venetian aristocracy.

The Tiepolo family goes back to the earliest times of Venice. They had positions of leadership when Venetia Marittima was still under the Exarchate of Ravenna. The family originated in Ravenna, and maybe in Rome before that. A Tiepolo was primicerius at the church on the Olivolo island in 706, before it became a bishopric, and Jacopo Tiepolo was Podestà of Constantinople after the Fourth Crusade, then Duke of Candia (Crete), and finally elected Doge in 1229. He donated the money to build the Basilica dei SS Giovanni e Paolo, and his sarcophagus is on the façade of the church.3

The Grimani family originated in Lombardy in the 700s, so they were in Venice from the very beginning. They were recognised as patrician with the Locking of the Council in 1297. The family boasted three Doges and a number of Procuratori di San Marco, senators, military leaders and ambassadors.4

The Diedo family is even more ancient. They fled Altino for the lagoon settlements at the time of the invasion of the Ostrogoths. At the Locking of the Council in 1297 they remained patrician. There weren’t any Doges in the Diedo family, but family members occupied many high positions over the centuries, such as Procuratore di San Marco, general, admiral and ambassador, besides roles in the Venetian church.5

Three Auditors — not one

All three men have the same title of Inquis. Revis. — inquisitore e revisore — inquisitor and accountant.

They were peers.

Most offices of the Venetian state did not have one person in charge, but a college of three. They would generally serve three years, with one replaced every year. In some cases, like the magistrato alla salute,6 there were six magistrates, one from each sestiere.

This was a system of checks and balances, implemented in many parts of the Venetian state, to avoid giving individuals too much power. All three provveditori or magistrati had to sign off on all decisions of the office they presided.

The signature of these three noblemen is what made this text the law of the land.

The secretary

Besides the three noblemen with the title of inquisitori e revisori, the proclamation also carries the name Lauro Bartolini, with the title of ‘secretary.’

That sounds like a clerk or a lower ranking office worker, but it is not.

If anything, he was more like a head of department.

Venetian society had a class of hereditary nobility at the top, especially after the Locking of the Council in 1297, but there were lots of other wealthy and sometimes ancients families in Venice. Some were families who didn’t make the cut in 1297, others were families who had become rich later, and others again came from the local nobility of cities which became part of the Venetian Dominio di Terra — the Venetian land dominion.

Some of these families formed the ‘Order of the Secretaries,’ which filled many leading, but second tier, positions in the Venetian state apparatus.

The Bartolini family were part of the nobility of Udine in Friuli from the 1500s, and held important posts in Venice from the 1700s.

In 1746, an Orazio Bartolini was elected Cancellier Grande, a position he held until 1766.7 The ‘Grand Chancellor’ was the highest position in the Venetian Republic available to cittadini — commoners. The Cancellier Grande headed the commoners, just like the Doge was the head of the patricians.

If Lauro Bartolini was from the same family, it would be perfectly normal for him to occupy a leading position in an important office of the state. It was a privilege of his social class, and given his family connections, almost expected.

The guy who made the slab

There’s one last line of the inscription, which is not part of the text of the law.

It was added by the man in charge of having the stone slab carved and mounted on the wall, so nobody henceforth could claim ignorance of the law.

The line Dì 22 Giugno 1759 Publicato per me Francesco Lanza Publico Commandador translates as “On the day 22nd of June,1759, published by me Francesco Lanza, Public Commander.”

The interesting part here is the “by me” bit.

Francesco Lanza wanted his bit of the glory of being associated with people in power, so he added himself to the inscription. The recognition of social status was essential in a society where social class meant everything.

Venetian law-making

This minor law of the Venetian Republic — covering activities on a single riva and fondamenta — was not made by an elected assembly with a formalised legislative procedure.

It was decided and made by four wealthy men, who represented their social classes in government.

Three of them belonged to the hereditary aristocracy which had created and which ran the Venetian state for over a millennium, and one belonged to the very top level of the commoners.

The three noblemen were descendants of families which had lived in Venice for a thousand years. The last was a commoner only because his family arrived too late to the party.

While Venice was a republic, it was very much not a democracy. It was, mostly, government by the rich for the rich.

Only minor laws were made in this way. Laws of constitutional importance, and of relevance to foreign policy and diplomatic relations, were decided by the entire Consiglio Maggiore. Other laws were made by the senate and other parts of the state, within their remit.

The idea of having a separate legislative branch of government, separate from the executive and the judicial branches, came about in the 1700s.

However, the organisation of the Venetian state had all but fossilised in the Middle Ages, notably with the Locking of the Council, so those ideas never became a part of the Venetian Republic.

It remained a medieval state to the end.

Footnotes

- ibid., p. 209, entry Inquisitori alle Scuole Grandi (my translation of the entry). For more about Venetian state institutions see State institutions of the Republic of Venice. ↩︎

- Lire di piccoli was a coin denomination, see Venetian coinage. ↩︎

- Schröder (1830), vol. 2, pp. 34-306. ↩︎

- ibid., vol. 1, p. 399. ↩︎

- ibid., vol. 1, p. 288. ↩︎

- Venice had a ministry for public health since 1485, due to the black plague and the subsequent need to gather information, to enforce the precautions taken, and to administer the lazzaretti. ↩︎

- Mutinelli (1851), pp. 84-87, entry Cancellier Grande. ↩︎

Related articles

- Venetian Patent law — 1474

- Prostitution in Venice

- Scuole Grandi and Scuole piccole

- Però l’anderà parte — vadit pars

- Inquisitori alle Scuole Grandi — Lessico Veneto

- State institutions of the Republic of Venice

- Venetian coinage

Bibliography

- Mutinelli, Fabio. Lessico veneto che contiene l'antica fraseologia volgare e forense … / compilato per agevolare la lettura della storia dell'antica Repubblica veneta e lo studio de'documenti a lei relativi. Venezia : co' tipi di Giambatista Andreola, 1851. [more] 🔗

- Schröder, Francesco. Genealogico delle Famiglie Confermate Nobili e dei Titolati Nobili, (2 vols.). Venezia, 1830.

Leave a Reply