What kind of food did common people eat in Venice in the 1700s?

Venetian Stories

This post is an issue of our newsletter — Venetian Stories — which goes out every few weeks, to keep in touch and share stories and titbits from and about Venice and its history.

We can learn something by looking at street names. Many Venetian alleyways have names after old trades or crafts, since people in the same line of business tended to stay in the same areas of the city. Many of those trades were related to food.

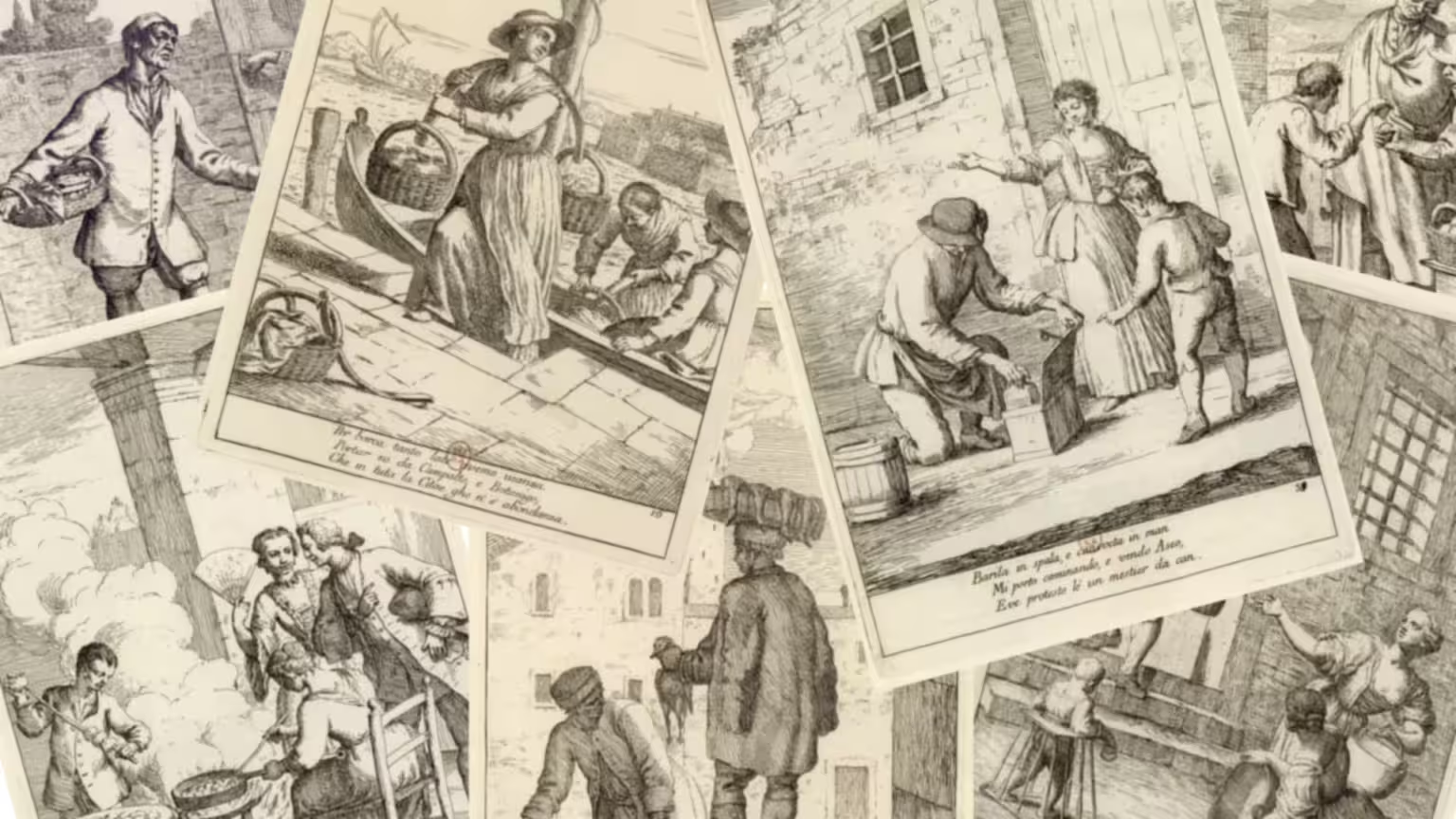

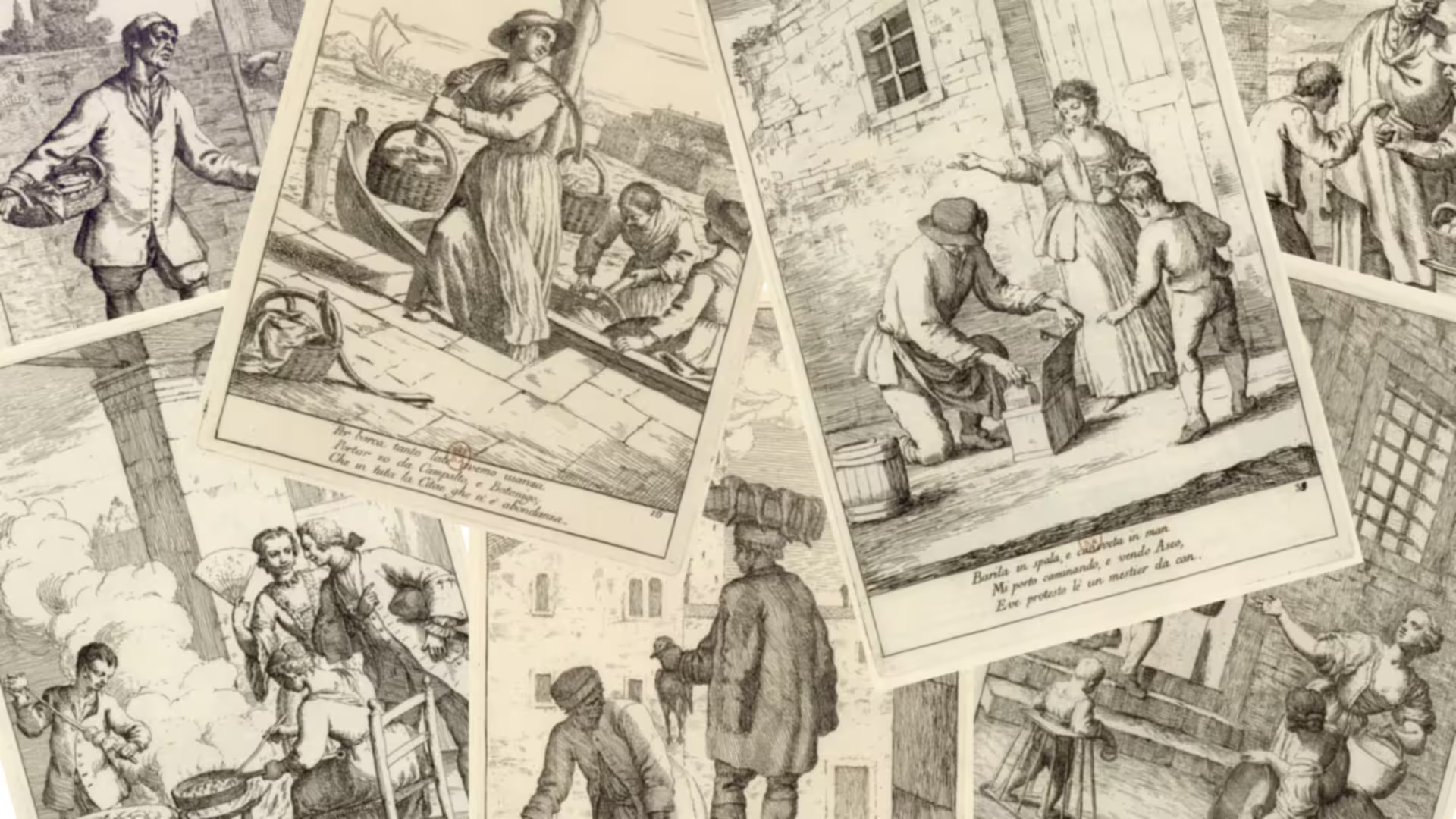

Another source is art, especially if we veer away from fine art into the more popular and commercial branches. Works, such as the Le arti che vanno per via nella Città di Venezia (1753) — The trades on the streets of the city of Venice — by Gaetano Zompini, can give us some idea about who circulated in the alleyways of Venice, peddling their wares.

Street food vendors

Of the sixty engravings in Zompini’s work on street trades, some nineteen plates are related to food and drink, and others are still kitchen related.

The only plate related to bread is collectors of bran, which they ground into a poor flour, to make bread to sell on the streets (plate 49 — Della Semola). This was clear bread for the poor.

There is also a vendor of polenta with butter and cheese (plate 37 — Polentina), but the inclusion of butter and cheese probably means that it is more in the street food department.

Fruit and vegetables are represented by the street vendor of vegetables and salad (plate 2 — Erbariol), of fruit (plate 29 — Fruttariol) and a peddler of sponges, brooms and citrus fruit (plate 45 — Sponze, Naranze , ec.), which is a rather strange combination of wares.

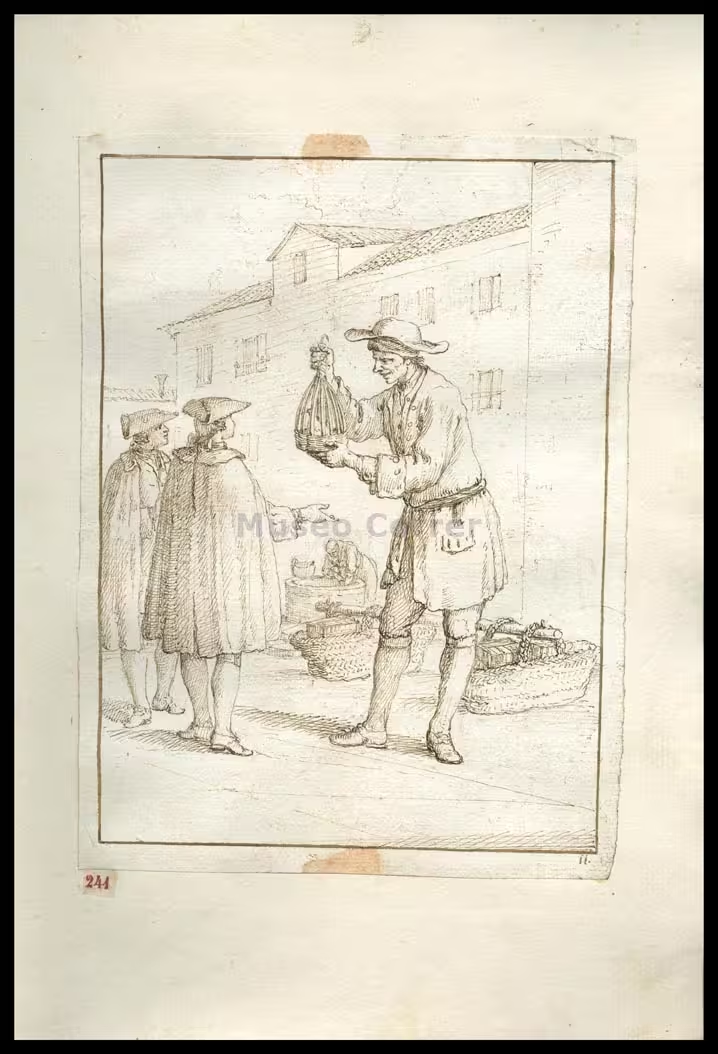

Animal produce is represented by vendors of game birds (plate 23 — Foleghe , e Mazzorini), farmers selling chicken (plate 47 — Contadin con Polame), and a door-to-door vendor of black pudding (plate 35 — Dolce de Vedeletto). There is also the seller of eggs (plate 12 — Dai Vovi).

Seafood offerings are purified mussels (plate 15 — Cappe), cooked ready to eat sea snails (plate 25 — Caraguoi) and the fisherman selling fish cheaper than at the market (plate 32 — Pescaor).

In the dairy department, we have milk from the mainland (plate 16 — Dalla Latte), and ricotta and cheese (plate 48 — Dalle Puine).

In the sweet end there are the vendors of sweet maize cakes with raisins (plate 6 — Zaletto), the sellers of bussolai and donuts (plate 17 — Scaleter) and the woman making fritters on the street (plate 31 — Frittole).

Finally, there’s the door-to-door seller of vinegar (plate 33 — Aseo) and of wine by the bucket (plate 60 — Vin in quarta).

Working hard for a few coins were the women carrying water from the wells (plate 24 — Porta Bigolo con acqua).

For kitchenware, there were street vendors of pots and pans (plate 14 — Pignate), wooden spoons and ladles (plate 40 — Cazze , e Sculieri) and the knife grinder (plate 21 — Gua).

Gaetano Zompini

Gaetano Zompini (1700–1776) was a talented artist and his paintings can be found in buildings in Venice, and in museums around Europe.

His background was probably not poor. He was born in a small town on the mainland, so he was not a Venetian citizen, but his family could afford to send him to Venice for an education as an artist.

He married, once he was settled as a painter in Venice, and got eleven children.

However, his economic success never really materialised. He struggled to get by with such a numerous family, and relied on patronage for work. When patronage dried up, he had problems supporting his family.

His eyesight diminished in the later years, and he eventually became completely blind. He died in 1778 in abject poverty.

The Le arti che vanno per via nella Città di Venezia wasn’t commercially successful until the 1785 edition, after the death of Zompini.

The coloured prints above are from a 1770 edition, and the uncoloured prints from the 1785 edition. The preliminary drawings Zompini made before etching the copper plates for printing, are in the archive of the Museo Correr in Venice.

All the available images for all the prints are available following the links above, including translation from the original Venetian of the short poems at the bottom of each print.

Leave a Reply