Well, actually, they’re cisterns.

Marin Sanudo, a Venetian historian and diarist from the early 1500s, famously said the “Venice is in the water, but it doesn’t have water” (original: “Venezia è in acqua ma non ha acqua”).

The conundrum is of course that there’s water and water. Fresh water, which is suitable for drinking, and the salt water of the lagoon and the sea, which is not.

Venice has much of the latter, but very little of the former.

Any normal well in Venice produces only salt water. The soil below the city is sand and mud, immersed in the water from the lagoon.

Drinking water was therefore a problem ever since the earliest settlements, which goes back at least to Roman times.

Rainwater

The only locally available source of fresh water in the lagoon is rain.

Since rain is intermittent, seasonal and unreliable, cisterns are essential. When it rains the water must be collected and stored for later use.

The structures we see around Venice and in the lagoon are in reality very elaborate and cleverly engineered rain water collectors and cisterns.

The origin of the rain water collecting cisterns must go back to the very first settlements in the lagoon. Our need for fresh water is biological and cannot be rescinded, but the first remains we have are medieval.

Some older wellheads in stone clearly resemble earlier wooden wellheads, which can give us an idea, but otherwise we know little of how the earlier wells looked.

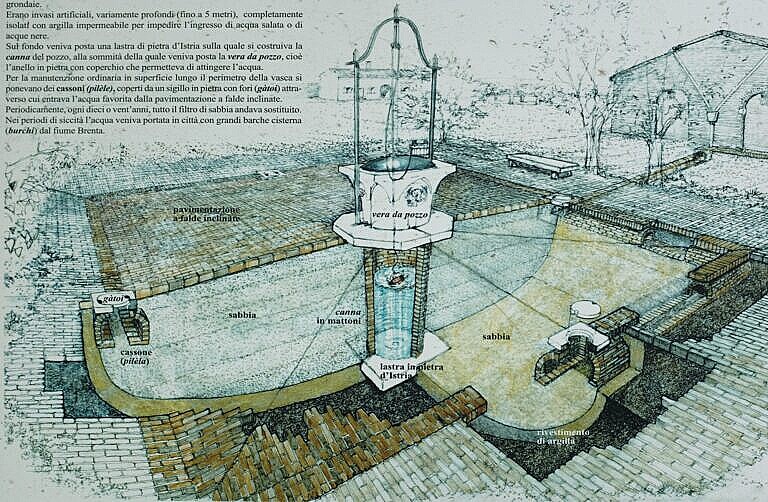

The structure of a well/cistern

Venice is built on mud, which deeper down becomes clay. At a depth of some four or five metres the density is such that the clay is practically impervious to water.

The Venetians knew this, so they’d dig a deep hole, three to five metres in depth, continuing until the clay was hard enough. Then they used the dense clay from the bottom, cutting it out in slabs, to line the sides of the hole.

They used manual pumps to keep the hole free from salt water.

A big flat stone at the bottom of the hole became the base of the actual well, which at this point would have looked like a tower standing in a hole.

Then they filled the hole up with sand and gravel, except for a few corners. Here they built a cavity in brick (cassone), surmounted by a stone with several drilled holes (gatoi).

The entire surface around the wellhead was inclined, a bit like a modern bathroom floor, so the rainwater would run towards the gatoi into the cassoni. From there it would filter slowly through the sand and finally through the bricks is the well itself.

Many roofs served rainwater collection too. A horizontal line of bricks at the edge of the roof prevented the water from running off the roof, creating a gutter. Vertical tubes within the walls of the building then channelled the water down into the cassoni.

In this way the surface area available for collecting rainwater became many times larger.

Thousands of wells

A population of over a hundred thousands, as Venice has had for most of its history, requires lots of water. Consequently, there were wells all over.

The most visible wells are the ones in public squares, and every campo has at least one well, and often more.

There were several hundred public wells in Venice. The sponsors often adorned the wellheads with their coat of arms or inscriptions.

Besides the public wells there were private wells, and they were much more numerous.

Every courtyard in Venice had a well, and sometimes more than one.

Every palace and every block of buildings had a courtyard, if not for any other reason than to host a well.

These private wells numbered in the thousands, up to five to six thousands.

Distribution of water

Rain water is by nature a limited and potentially scarce resource. It might be plentiful or absent, and it is usually less abundant at the times of year when it’s more needed.

Consequently, the authorities controlled and rationed the water from the wells. A lid prevented unauthorised access.

The person in charge of the public wells was most often the parish priest.

In the Venetian language, rain is piova and one of the words for a priest is piovàn.

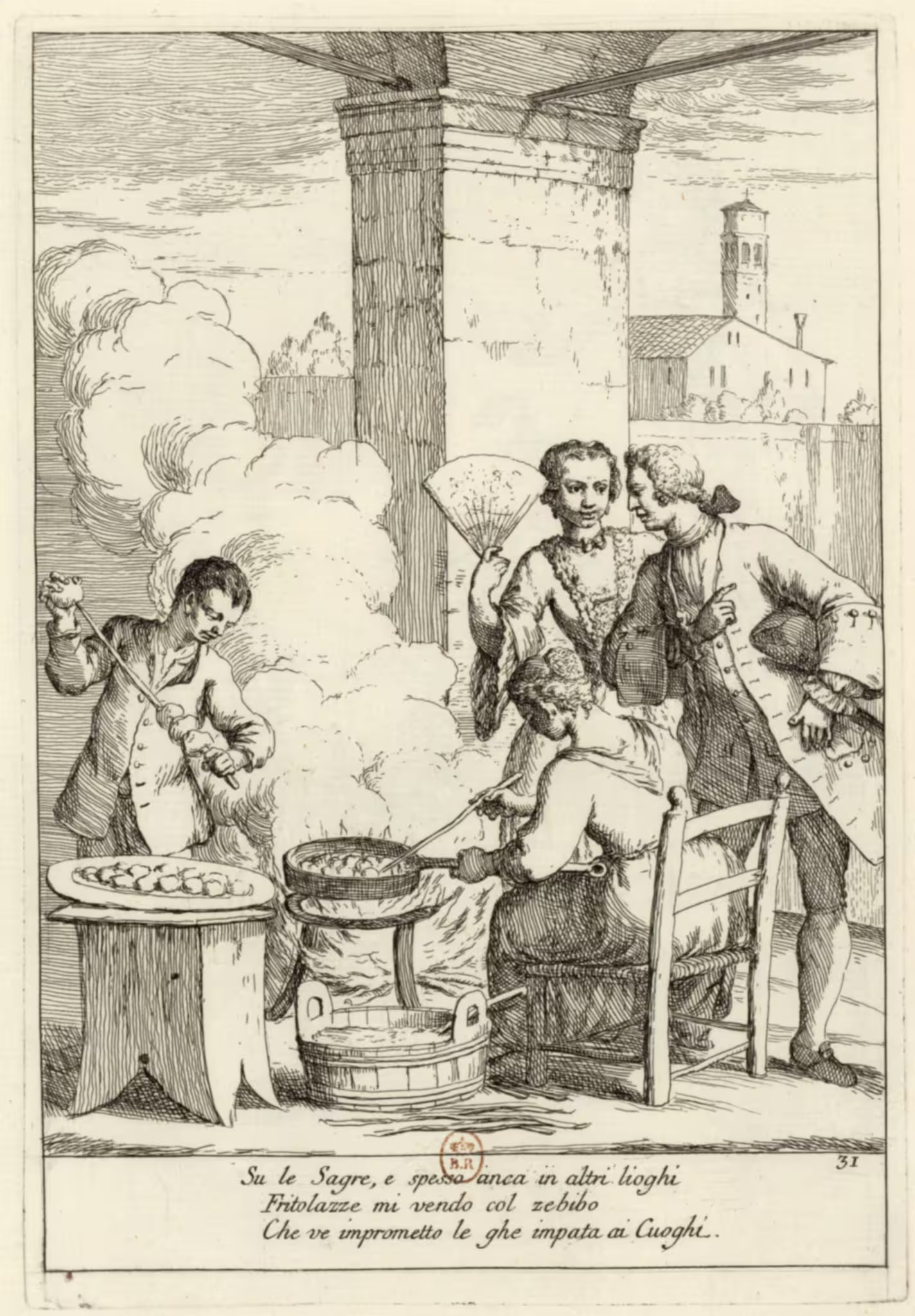

The acquaroli

While Venice couldn’t rely entirely on river water for its water supply, the Venetians did use the rivers on the mainland to supplement the potentially scarce rainwater supply.

The acquaroli were a dedicated guild charged with ferrying river water to Venice and distributing it throughout the city, wherever it was needed.

They had a monopoly of supplying water to industry and businesses, which could not take water from the public cisterns.

The acquaroli who weren’t members of the guild could only sell their water to private citizens, and their boats doubled as rubbish boats, called scoazzere, as they went empty from Venice to the mainland.

What ends well …

The water supply of Venice was based on rainwater using such wells or cisterns until the 1880s, when an aqueduct was built to supply Venice with groundwater from the foothills of the Alps.

The wells were closed for good, and replaced with cast iron fountains with constantly flowing fresh water.

In some cases, the cisterns were repurposed for storing the water from the aqueduct, and the fountainhead mounted directly on the side of the ancient wellhead.

Many of these fountains are still running, for tourists and locals alike, even if everybody now has running water in their homes.

Gallery

Leave a Reply