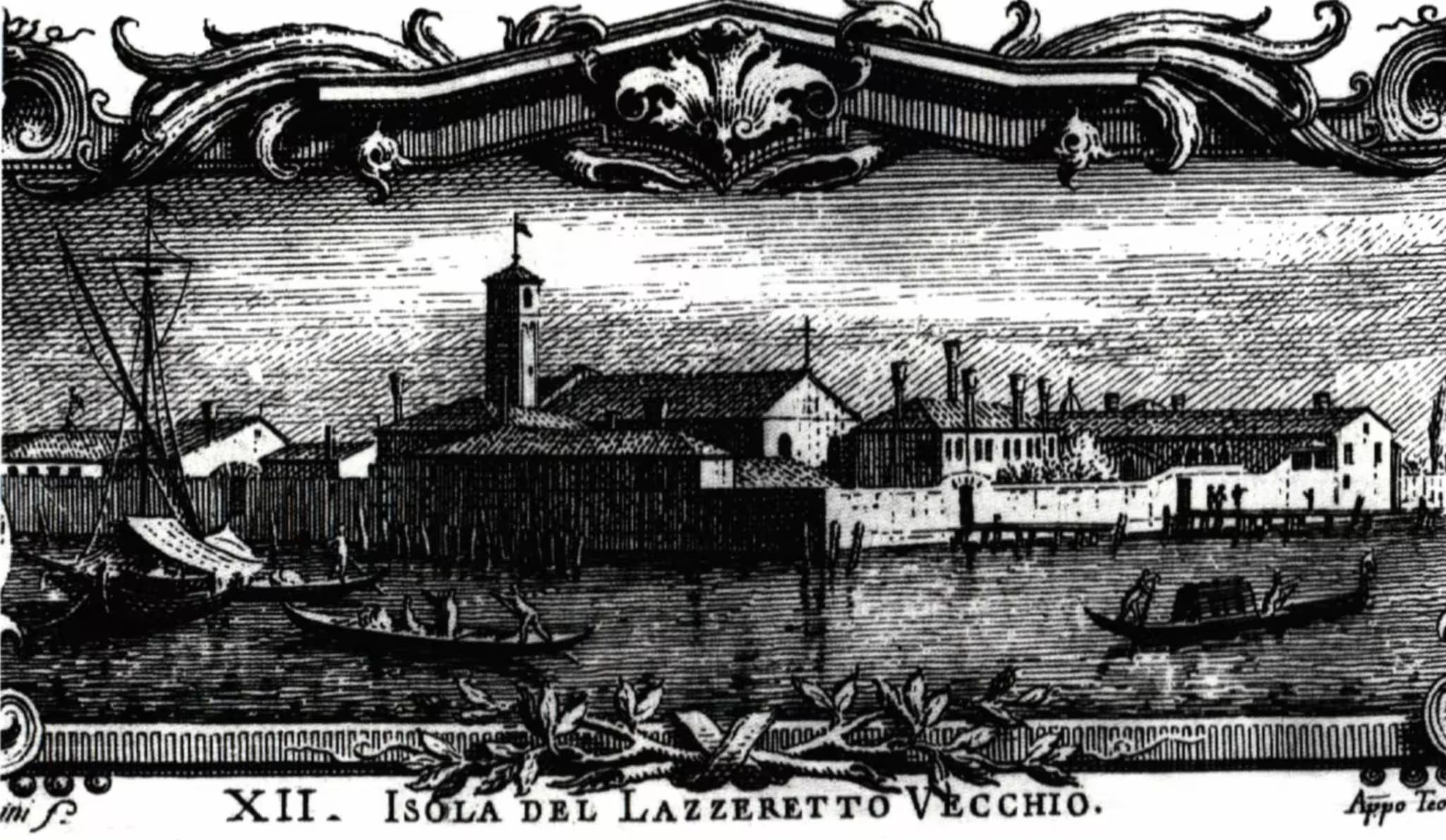

For three centuries, Lazzaretto Nuovo was the main quarantine station guarding the city of Venice from the bubonic plague.

Merchandise, as well as people, were kept in quarantine, and the goods underwent a series of treatments to cleanse it. The people doing this risky work, referred to with the Venetian word bastazi, often came from the areas around Bergamo and Brescia, then under Venetian rule.

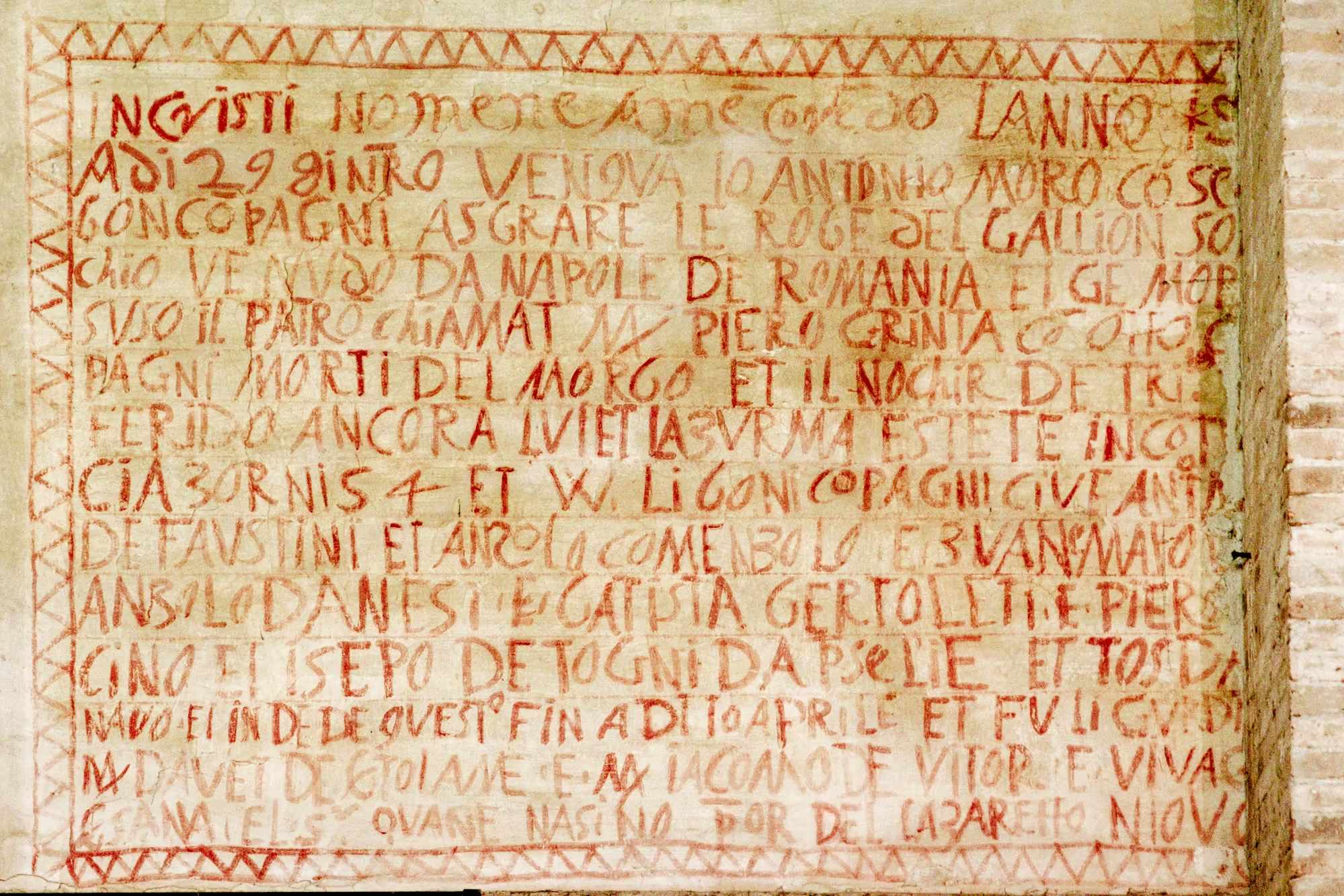

One of them, Antonio Moro from the small mountain village Preseglie close to Brescia, left a message on the wall of the main building for us to read four centuries later.

Transcription

In Cristi nomene ame(n). Core(n)do l’anno 15[93], a dì 29 gin(a)ro veni qua io Antonio Moro co(n) sete | boni co(m)pagni a sborare le robe del gallion Somachio venudo da Napole de Romania; et ghe morì | suso il patro(n), chiamat M(isser) Piero Grinta, co(n) otto compagni morti del morbo, et il nochir de Tripoli, ferido ancora luì e la zurma, e stete ìn contumacia zorni 54. Et W li boni co(m)pagni. Ci vene Antonio de Faustini et Anzolo Comenzalo et Zuane Mato et Anzolo Danesi e Batista Bertoleti e Piero Cino et lsepo de Togni da P(re)selie et Tos da Navo et inde de quest(o) fin A dì 10 aprile. Et fu li guardiani M(isser) Davet de Bontolamè et M(isser) Jacomo de Vitor; e viva e sana el s(ior) Zuane Nasino p(rior) del Lazaretto Niovo.

Translation

In the name of Christ, Amen. In the year 15[93], on the day 29th January, io Antonio Moro came here with seven good companions to cleanse the merchandise of the gallion Somachio, which came from Napoli di Romania, and thereupon died the owner, called Mr Piero Grinta, with eight companions dead by the decease, and the helmsman from Tripoli, sick also, and the crew stayed in isolation for 54 days. And long live the good companions. There came Antonio di Faustini, and Angelo Comenzalo, and Giovanni Mato, and Angelo Danesi and Battista Bertoleti and Piero Cino and Giuseppe de Togni, from Preseglie, and Tos from Navo, and they stayed here until April 10th. The guardians were Mr. Davide de Bontolame and Mr. Jacomo de Vittor, and long live and good health to S(ir) Giovanni Nasino, prior of the Lazzaretto Novo.

There’s quite a bit in this text to unpack.

The language of Antonio Moro

The text is not in Italian because the Italian language did not exist at the time of Antonio Moro. The Italian language only came about after the unification of Italy in 1859-1866, and then in the form of a Tuscan dialect elevated to the status of national language.

Rather, Antonio Moro wrote in a Brescian dialect of Lombard, which was the regional language of Lombardy before the unification of Italy.

Brescia, and also Preseglie, came under the domination of the Serenissima in 1427, a long time before Antonio Moro was born. The workers travelled to Venice because there they had more rights and protections, rather than towards Milan, which was in another state.

Who was Antonio Moro?

Antonio Moro was most likely the leader of a team of bastazi. They were the workers who did the manual and dangerous work of trying to disinfect the merchandise of the contagion of the plague.

Most of the group came from Preseglie, a mountain village close to Brescia. One of them, however, came from a nearby village named Navo. We don’t know how he came to be there, but he could have stayed behind from the previous work crew to make some more money.

Many of the bastazi who worked at the Lazzaretto Nuovo came from the areas around Brescia and Bergamo. Antonio Moro and his companions must have travelled the 200km by foot in late January 1593. They arrived at the Lazzaretto Nuovo on the 29th. After April 10th, when they left the Lazzaretto, they would have walked back.

We can only guess why the bastazi at the Lazzaretto Nuovo came from far away. The work was very dangerous, and maybe the people living in and around the Venetian lagoon had better and safer options. For the people from the mountains in Lombardy, the association with Venice gave them options others didn’t have, and the work might have been a supplement to what they did back home.

That Antonio Moro knew how to write shouldn’t surprise us. It was a legal requirement of the Serenissima for doing the work he did.

The Galleon Somachio

The ship Somachio was a Venetian galleon. They could have a displacement of up to several hundred tonnes, with a crew of 50–100 men.

They were large enough and seaworthy enough to be able to prowl the Mediterranean also in the winter. Galleons would often travel armed with cannons.

The writing by Antonio Moro tells us a bit about the specific galleon that had brought in the merchandise that his work crew disinfected during their stay on the Lazzaretto Nuovo.

The Somachio belonged to a tradesman named Piero Grinta, who must have been rather wealthy to own such a large ship.

The galleon arrived in Venice on January 29th, 1593, from Napoli di Romania, as the Venetians called the city now called Nauplia on the Peloponnese in southern Greece. The name Romania doesn’t refer to the modern country Romania, but to the eastern Roman Empire. Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1543 (exactly 150 years earlier), but the Venetians kept using the name Romania.

When the Somachio left Greece, it had apparently embarked not only the merchandise but also the yersinia pestis, the bacteria causing the bubonic plague. During the journey, the owner Piero Grinta died of the plague, and with him another eight sailors or travellers.

Most likely, their corpses were thrown in the sea with a minimum of ritual.

The Helmsman from Tripoli

At arrival in Venice, the plague was still on board. We know this because Antonio Moro wrote that the helmsman ‘from Tripoli’ was ‘wounded’ by the decease. The unfortunate man would have been taken directly to the Lazzaretto Vecchio where the sick were kept in isolation.

We don’t know if he survived or perished. If he died, he would have ended his journey in a mass grave on the Lazzaretto Vecchio or on some other lagoon island. If he was lucky and survived the plague, he would have been taken to the Lazzaretto Nuovo to finish the quarantine with the rest of the crew.

Tripoli could be any one of a number of cities with that name. It’s a very common name in the Greek cultural sphere, meaning simply tri-city.

It so happens that there is a Tripoli on the Peloponnese very close to Nauplia. The helmsman might have been Greek and embarked on the Somachio there. He could also have been Libyan or Lebanese.

He could have been Christian or Muslim. There was a Muslim graveyard on the Lazzaretto Nuovo, alongside the Christian graveyard. It must therefore have been fairly common to have Muslim sailors and travellers on the ships arriving in Venice.

Quarantine

When a ship arrived in Venice with the plague on board, or without the required sanitary certificates, the plague doctor inspected the ship and the crew.

Whoever the doctor deemed sick were taken to the Lazzaretto Vecchio. The rest of the crew, the merchandise and the ship itself went to the Lazzaretto Nuovo for quarantine and disinfection.

The Lazzaretto Nuovo was subdivided in the ten sections separated by tall walls. Seven of these areas were for the quarantine of people, and the crew of the Somachio would have been taken to one of these areas. Antonio Moro writes that they were kept in isolation for 54 days.

This is more than the forty days indicated by the word ‘quarantine‘ (quaranta = forty) which is because the decision to settle for forty days of isolation happened later, in the 17th century. Before that, the period could be twenty, thirty, forty or, as in the case of the Somachio, even 54 days.

In fact, Antonio Moro doesn’t use the word ‘quarantina‘, but ‘contumacia‘ which means ‘isolation’.

The Guardians

Antonio Moro mentions two guardians in his text. Hi gives their names, and titles them M which is short for Messer, like Monsieur in French.

This indicates that they were above Antonio Moro on the social ladder.

The work of the guardians was to keep order within the Lazzaretto Novo, and to ensure that there was no cheating with the merchandise.

The Lazzaretto Nuovo was a kind of sanitary prison. The people inside weren’t there of their own volition. They were locked up under armed guard because they were considered a threat to public health.

Archive documents show that cheating and fiddling with the merchandise was quite common, like swapping goods of high value with goods of lower value, for which the bastazi would be paid afterwards.

There was little point in stealing within the Lazzaretto because you couldn’t get away. The bastazi were locked up just as the sailors and travellers.

The work of the bastazi

Three parts of the Lazzaretto Nuovo were used for cleansing the merchandise. Antonio Moro and his companions worked in one of these, called the Tezon Grando verso Venezia. His writing is on the wall of the Tezon Grando, the main building on the island.

When the Somachio came in, the ship was unloaded, and an inventory drawn up. Then all the merchandise was taken into the Tezon Grando, where Antonio Moro and his team would take over.

We don’t know what kind of merchandise the Somachio had on board, which is rather intriguing as the bastazi spent months (all of February and March, plus a bit) working with these goods, yet Antonio Moro doesn’t mention it.

The Venetians didn’t know what caused the plague. However, they had made their observations and the remedies they applied weren’t all useless.

Cloths would be washed repeatedly in fresh and salt water, and aired, dried. They would be exposed to the fumes of burning herbs like rosemary and juniper. Sponges would be kept in salt water for long periods, and metal objects immersed in vinegar.

The bastazi would be paid afterwards by the owner of the merchandise. After all, the owner would be able to sell the goods before the bastazi were done.

However, the owner of the merchandise of the Somachio, Piero Grinta, had died of the plague at sea.

The prior of the Lazzaretto Nuovo

The Lazzaretto Nuovo was managed by a priore, who was responsible for the daily running of the place. He was a layman, had to be married, and served four or five years.

The prior of the Lazzaretto Nuovo in 1593 was Zuane Nassin. He is mentioned in Antonio Moro’s writing, at the very end, where he is wished long life and good health.

The presence of Zuane Nassin as prior of the Lazzaretto Nuovo is attested by documents in the Italian State Archives from the Magistracy alla Salute of the Serenissima.

The Magistracy alla Salute was more or less the ministry for public health of the Serenissima. The prior of the Lazzaretto Nuovo and all the guardians were nominated directly by the magistrate.

The day after the Somachio arrived at the Lazzaretto Nuovo, on January 30th, 1593, the prior Zuane Nassin presented himself at the offices of the Magistrato alla Salute in Venice. With him, he had documents attested by a notary, that he was the legal heir to the merchandise on the Somachio that had belonged to Piero Grinta.

The prior of the Lazzaretto Nuovo could not be the beneficiary of wills for goods present in the Lazzaretto. There had been numerous causes of blackmail and fraud in the past, where priors had coerced persons to isolation to name them as beneficiaries in their wills.

Zuane Nassin had to approach his superiors to get his inheritance. He needed to present documents from before the arrival of the Somachio that he was the heir. He had such documents, from 1588, and he did receive his inheritance.

The gives us a clue to the last unanswered question.

Why Antonio Moro?

Over three centuries, thousands of workers passed the Lazzaretto Nuovo, working a few months before heading home.

There is no way they could all have left writings on the wall. There is not enough space. In fact, only a few of the bastazi have left anything beyond a few words.

Yet Antonio Moro was given a huge area, highly visible, to leave his and his companion’s names, and explain what they had done there.

Why Antonio Moro? Why not one of the other thousands of nameless, forgotten workers from the hills of Lombardy?

The answer is probably that the owner of the merchandise Antonio Moro and his crew were disinfecting, happened to be also the prior of the Lazzaretto Novo, and hence the benefactor of their work.

If Antonio Moro and his companions did a good job cleansing and not ruining the goods, the prior of the Lazzaretto Nuovo would be a bit better off, so naturally he wanted them to be content and feel appreciated. One way of doing that at no cost to himself could be to offer them a bit of the wall in the building where they worked, to leave their mark.

Related articles

- Lazzaretto Nuovo – the first quarantine station

- A Chronology of the Lazzaretto Nuovo

- Capitoli Da osservarsi nelli Lazaretti — 1674

Bibliography

Fazzini, Gerolamo (ed.). Venezia : isola del Lazzaretto Nuovo in Guide archeologiche della Laguna di Venezia. Archeoclub Venezia, 2004.

Fazzini, Gerolamo (ed.). I Lazzaretti Veneziani : il sistema sanitario della Serenissima contro le epidemie. Marcianum Press, Venezia, 2024.

Malagnini, Francesca. Il Lazzaretto nuovo di Venezia : le scritture parietali in Storie d'Italia. 2017.

Leave a Reply