On March 18, 1618, the Collegio received Sir Henry Wotton (1568–1639), the ambassador of the King of Great Britain to the Republic of Venice, who had a rather odd request.

Venetian Stories

This post is an issue of our newsletter — Venetian Stories — which goes out every few weeks, to keep in touch and share stories and titbits from and about Venice and its history.

The audience is described in the Venetian archives.

MDCXVIII. XVIII Marzo. (In Collegio).

Having come to the Most Excellent College, the Ambassador of the Majesty of England said as follows:

Illustrissimi et Eccellentissimi Signori, although I have come to your Excellencies for another occasion, however, I first want to beg you to be among the first to receive my office of condolence for the loss of the Most Serene Prince, Lord of great virtue and goodness, and an excellent patriot. Of course, such were always his most worthy conditions; but since human frailty brings with it from birth this necessary fall, thus enjoying the form of this Most Serene Government a permanent position, not subjected to the revolutions of the accidents of a single person, I pray heaven always preserve it from the snares of its enemies and make it prosper to the full extent of what you so highly deserve.

[…]1

Now I will move from a very just invective against unjust spirits to a compassionate intercession of grace. The Lord Count of Oxford, Great Chamberlain of Great Britain, these last days of Carnival, being in his gondola with a courteous young woman with him, a thing permissive by the quality of the time, for a certain recreation, did not know the order of the laws; the girl and the servants were placed in prison; and he, who knows that they have no blame in that matter, feels great regret for their suffering, and begs Your Excellencies for relaxation, and at his request I willingly add my heartfelt prayers.

And having been told on both points that consideration would be given, taking leave, he left.

Leggi e memorie venete sulla prostituzione fino alla caduta della Republica (1872), case document 135, p. 342–343.

Doge Giovanni Bembo died on March 16th, 1618, which is why Wotton started this way.

The interesting part is the second. What was this courteous young woman with whom the Earl went around for recreation, and why is she, and others, in prison?

In the original Venetian, we have una giovine cortese, that is, a courtesan, or more mundanely, a prostitute.

Henry de Vere, 18th Earl of Oxford, and Great Chamberlain to the King of Great Britain, had publicly enjoyed some recreation during carnival, with a ‘public prostitute,’ as they were often called in official documents.

The Earl of Oxford

Henry de Vere was born in 1593, and inherited the title of Earl of Oxford in 1604 at the death of his father. After the death of his mother in 1613 he inherited some money, which he used to go travelling.

In 1617, aged 24, he was in Venice, where he tried to offer his help to the Republic of Venice in the final stages of the War of Gradisca.

As is clear from the request of Sir Wotton above, he was still in Venice after the carnival of 1618.

He returned to England in late 1618. Ever in search of honour and recognition, he participated in several military conflicts on the continent, and he died of a fever in 1625, during a campaign in the Low Countries.

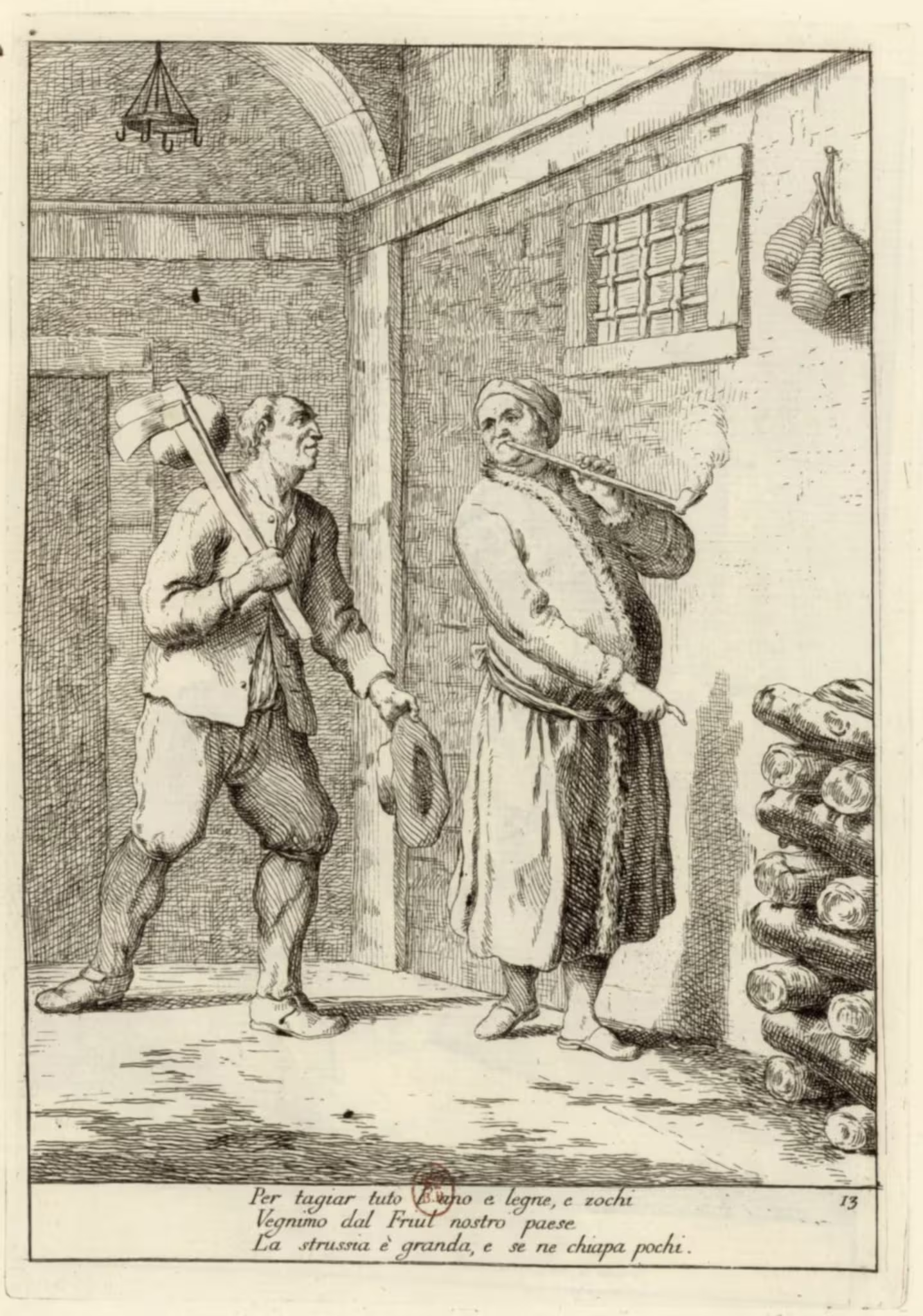

Prostitutes in gondolas

Apparently, during the carnival of 1618, Henry de Vere embarked a young courtesan on his gondola. All for a certain recreation in line with the mores of the time, as ambassador Wotton excused him.

In the boat were also some of his servants, and, of course, some rowers.

They all broke the law, while he didn’t.

The girl, the rowers and the servants consequently all ended up in jail.

The law of the land

What were the laws the young woman had broken by accepting a ride in the gondola of the Earl of Oxford?

The Council of Ten decreed on June 30th, 1615, that:

Let it be decided that in the future it will be completely forbidden for public prostitutes to go by boat in this city during the day, nor at night in masks or without masks with the windows of the felze2 open or closed, nor to go in any dress whatsoever to parties or weddings of noble and honest people, or to festivals, feasts, villa balls, in churches and at fairs and other public places in the cities, lands and places of our State in a carriage or in another way: and furthermore, they shall be absolutely prohibited from allowing games of cards, dice or anything else to be played in their homes, under penalty of five years of prison and furthermore of having the nose and an ear cut off between the two columns of San Marco for the administering of justice, or placed in pillory and whipped from San Marco to Rialto …

ibid., law document 138, p. 137–138.

The Council of Ten delegated enforcement of such laws to the Esecutori contro la biastemia — the Executors against Blasphemy.

This law was reiterated — for the expressed purpose of making sure the law was known and respected — by the Most Excellent Lords Executors against Blasphemy just a few months before the date of the crime, in a proclamation of December 19th, 1617.

These are just some of the last laws and proclamations — relative to the date of the crime in question — trying to curb the ostentatious behaviour of the Venetian prostitutes.

Restrictions on their dress, and on when, where and how they could move around the city, and on what activities were allowed in their homes, were introduced and repeated again and again.

The repetitiousness alone tells us that the rules were habitually ignored.

But the servants?

What had the servants of the Earl of Oxford done to deserve prison?

The same law also states:

Boatmen, coaches and servants who do not come to report them immediately are to be condemned to the galleys with irons on their feet for five continuous years, and in case of incapacity their strongest hand is to be cut off so that it separates from the arm, and remaining absent, they are banished for twenty years from all the lands and places of our Dominion between the Menzo and the Quarner3 with a reward of six hundred lire to the captors, or interfectors, and being caught in counterfeit they remain condemned to the oar as above.

If any servant, coach, boatman or other person, no one excepted, accuses any of the aforementioned prostitutes who have transgressed, so that through his denunciation the truth is clarified, he shall receive, in addition to impunity of any complicity, cooperation or knowledge in the crime, six hundred lire …

ibid., law document 138, p. 138.

Law enforcement in the Republic of Venice relied almost exclusively on informants. Such informants were therefore rewarded and promised secrecy, but if somebody with knowledge of a criminal act didn’t report it, they became complicit in the crime.

Informing was thereby encouraged, both by stick and carrot.

Perpetrators and not

In all this, the main perpetrator is the young courtesan. The rowers and servants were involved by association, for not reporting her crime.

The only person who didn’t commit a crime by being in that gondola, was young English aristocrat Henry de Vere.

Yet, the girl and the men probably only did what they did because the Earl of Oxford asked them to, and paid them for it.

Could they have refused?

The Republic of Venice was as much a class society as any other in Europe, and for people of low standing to disobey or oppose the wishes of upper-class individuals could be costly and dangerous.

The story of Angela Zaffetta and Lorenzo Venier is emblematic of what could happen if a young courtesan turned down an aristocrat, and she might even have got off lightly, with only damage to her reputation.

People were taught from early on in life to obey their superiors. Stories about how common people didn’t get punished for obeying their superiors were common. The legend of the fisherman is only one such story.

The plea for clemency

There can be little doubt that Henry de Vere, when he heard about the fate of the people he had employed for his recreation during carnival, went to Sir Wotton to ask for his intercession.

The carnival of 1618 ended in late February, and Sir Wotton met with the Collegio on March 18th, at least three weeks later.

Alas, we don’t know of any decision by the Collegio, by the Council of Ten or by the Esecutori in the case.

They might have considered the cases, as they promised, or they might not have. They might have decided one way or the other, without leaving much of a paper trail, or the documents might have been lost. There was a shroud of secrecy around the deliberations of the Council of Ten, which tended to leave few documents in the archives. It is not inconceivable that the heads of the Council of Ten simply sent a messenger to the prison with an order to let the persons go.

Still, we can speculate, but we do not know.

We also don’t know the names of the persons involved, besides Henry de Vere.

Notes

- The omission is a story about how an imprisoned criminal had tried to buy the favour of the ambassador by passing him military secrets through a servant. The ambassador brought the purported secrets to the Council of Ten, with a wish that the criminal might remain in prison forever, for all he cared. ↩︎

- The felze is the cabin which gondolas used to have until the 1800s. There were often small window openings, which could be open or closed. ↩︎

- From the Mincio river in Lombardy to the Quarner river in Istria, that is, the entire land dominion of the Venetian state. ↩︎

Bibliography

Da Mosto, Andrea. L'Archivio di Stato di Venezia : indice generale, storico, descrittivo ed analitico in Bibliothèque des Annales Institutorum, 5. Roma : Biblioteca d'arte, 1937.

Leggi e memorie venete sulla prostituzione fino alla caduta della Republica, a spese del conte di Oxford, 1870-72. Venezia, Tipografia del Commercio di Marco Visentini, 1872.

Related articles

- An authorless book

- Prostitution in Venice

- A catalogue of Venetian prostitutes

- Catalogue of all the principal and most honoured Courtesans of Venice (translated)

- Catalogo di tutte le principal et più honorate Cortigiane di Venetia (original)

- An Englishman in Venice — the diary of John Evelyn — 1645