On a cold February day, in the year of the Lord 1340, an old and tired fisherman had sought refuge from a violent deluge under the Ponte di Paglia, just at the corner of the Palazzo Ducale.

Venetian Stories

This post is an issue of our newsletter — Venetian Stories — which goes out every few weeks, to keep in touch and share stories and titbits from and about Venice and its history.

In all his life he had never seen such a downpour.

Suddenly somebody called the fisherman from the shore besides the palace. The fisherman looked up, and saw an expensively dressed, very old man, a bit like a priest or a bishop but yet unlike any man of the cloth the fisherman had ever seen before.

«I need you to take me to the island across,» said the old man. «It is very important.»

The fisherman made weak gesture at the rain which totally obscured the island of San Giorgio Maggiore, even though it wasn’t very far.

The rain didn’t seem to bother the old man. «Don’t worry,» he replied, «you’ll be perfectly safe with me.»

The old man was clearly somebody important, and the poor fisherman didn’t have the courage to disobey. He stood up, as well as he could under the bridge, grabbed his oars and manoeuvred the boat towards the old man on the shore.

The old man stepped easily into the boat, and the fisherman started rowing towards the invisible island across.

The rain wasn’t actually that cold.

The island soon came into sight, and the fisherman saw a young man standing on the shore. He was dressed as a soldier, with a lance and a sword by his side, but he didn’t look like any Venetian soldier the fisherman had ever seen.

As soon as the boat was close to the shore, the soldier stepped lightly into the boat.

The two men clearly knew each other, as they remained standing close together in the boat.

«Now,» said the old man, «take us both to the church on the Lido.»

«But,» started the fisherman, but the two men had turned their back on him, as they look towards the Lido, invisible in the distance.

The fisherman started rowing again, this time towards the Lido.

It took a while, and all the time two passengers, the old bishop-like figure and the young soldier, stood silently in the boat, looking towards the Lido unperturbed by the rain and wind.

They arrived near the church on the Lido, and the fisherman saw a figure on the shore. As they moved closer, he could see it was a bishop.

The bishop too stepped into the boat, so lightly it hardly moved.

«To the sea,» he said, «as fast as you can. It is important.»

The fisherman wanted to object, but all three figures had their back towards him, looking towards the sea.

He rowed on as instructed. Who was he to oppose soldiers and bishops.

As the little boat left the lagoon and entered the sea, the waves became larger and the sky darker, but somehow the boat remained stable, and the fisherman kept rowing.

His father had taught him to row and fish as soon as he could walk. He he had spent almost all the nights ever since rowing and fishing in this small boat. He had rowed in bad weather before, but never had he rowed into the open sea in the middle of a storm.

An eery sound of screaming seemed to mix with the howling winds, and the fisherman look forward.

A large ship was approaching the small boat. It was pitch black, its sails were torn, but still it moved steadily forward.

As they moved closer the screaming became louder. It was stronger than the wind.

A dark figure on the bridge steered the ship. A multitude of smaller figures were working on the deck and climbing the rigging.

They had tails and horns. So had the figure steering.

The three men in the fisherman’s boat straightened up, and looked directly at black ship. They almost glowed in the dark.

Each of them raised their right hand in front of them, and made the sign of the cross.

The sea opened up in front of them, and the black ship with the Devil and all his daemons fell into the abyss.

When the sea closed again, the water was calm, the sky was clearing and the wind and rain had stopped. The morning sun was low on the horizon.

The bishop turned around and looked at the fisherman. «Take me back to my church,» he said.

The fisherman turned the boat around, and rowed back towards the lagoon.

When they arrived at the church the bishop stepped out of the boat, and in the blink of an eye he was gone.

The soldier now turned around. «Take me back to my island,» he commanded the fisherman.

On the island he stepped onto the shore and disappeared.

The old man now turned around. «Bring me back to the palace, my friend.»

The fisherman obey, and took the old man back to the Ponte di Paglia. As the old man stepped out of the boat, he turned around and handed the fisherman a golden ring.

«Take this,» he said, «to the Doge, who is meeting his council this morning, and tell them what has happened.»

The fisherman looked at the ring his hand. It was heavy, and ancient, and probably worth more than all the fish he had ever caught in his entire life.

He looked up, but the old man was gone.

This was not the time to be disobedient, so the fisherman tied down his boat and walked up to the palace entrance. He approached the guards.

«I have been told to bring this ring to the Doge,» he said, holding out the ring in his open hand.

The guards looked at the fishermen, then at the ring, then at each other. One of them went into the palace, and soon after returned with a nobleman.

«Show me the ring,» he commanded.

The fisherman obeyed.

The nobleman looked carefully at the ring, but didn’t touch it. After a while he said: «Come with me.»

Together they walked up fine stairs, along a portico, through several rooms so fine the fisherman couldn’t believe his eyes. They arrived in a room, with a table at the centre with seven men sitting around, three on each side and one at the head of the table.

They were dressed in gold and silk, but weren’t as fine as the old man.

The fisherman was taken to the Doge at the head of the table.

«Show the ring,» ordered the nobleman.

The fisherman held out his hand, palm open with the ring.

«How did you get this,» said the Doge in a very stern voice.

The terrified fisherman told the story of the three men and the ship at sea.

When he had finished they all remained in silence for a while, until the Doge spoke.

«Have there been any disturbances around the chapel or the treasury?» he ask the six councillors around the table.

The six all shook their heads.

«Then his story mush be true,» the Doge said. «How else can this poor fisherman be in possession of the very ring St Mark wore on his finger?»

«St Mark,» repeated one of the councillors.

«St George, the soldier,» added another.

«And St Nicholas, the bishop,» said a third.

Legends

This legend has been retold in different forms in several chronicles. It was a well known story about how the trinity of the saints Mark, George and Nicholas would keep Venice safe from all dangers.

Legends and narratives are important in all societies, and all societies have them. They serve to explain the existence, strength and durability of a society, and to create social cohesion between different classes, to justify social differences, to create a sense of belonging, and a sense of shared identity.

The repeated retelling of this legend made it part of the Venetian national myth.

We don’t know when the legend originated, which might have been later than the alleged date of February, 1340 or 1341 or 1342, because, as always, the sources don’t agree. It was clearly a part of the national narrative in the late 1400s.

There are several purposes of this legend.

Firstly, it underlines how Venice, even when in grave danger, was strong because it had powerful supernational protectors. Venice was not a great power yet in the 1300s, and it fought many wars with its neighbours. Venice often won, but not always. In the War of Chioggia (1379-80) against Genoa, Venice fought for its survival within the confines of the Venetian lagoon.

Secondly, the fisherman obeyed his superiors, and in doing so he did the ‘right’ thing.

Thirdly, it shows the authorities in the Venetian state as benevolent. The Doge and his councillors believed the story and didn’t punish the fisherman for being in possession of a treasure he clearly shouldn’t have.

Scuola Grande di San Marco

The Scuola Grande di San Marco — another great Venetian institution with St Mark as its patron saint — decided in 1534 that it needed one or two canvases for one of the main halls upstairs.

Naturally, it would have to feature St Mark.

The painter Paris Bordone won the competition with his painting of the fisherman delivering the ring to the Doge, in a rather imaginary environment.

The Doge at the time of the event would have been Bartolomeo Gradenigo However, in the painting Borbone depicted Andrea Gritti, who was the Doge at the time of the commissioning of the painting. I guess it is never a bad idea to ingratiate yourself with the people in power.

The school already had another painting recounting the same legend of the fisherman.

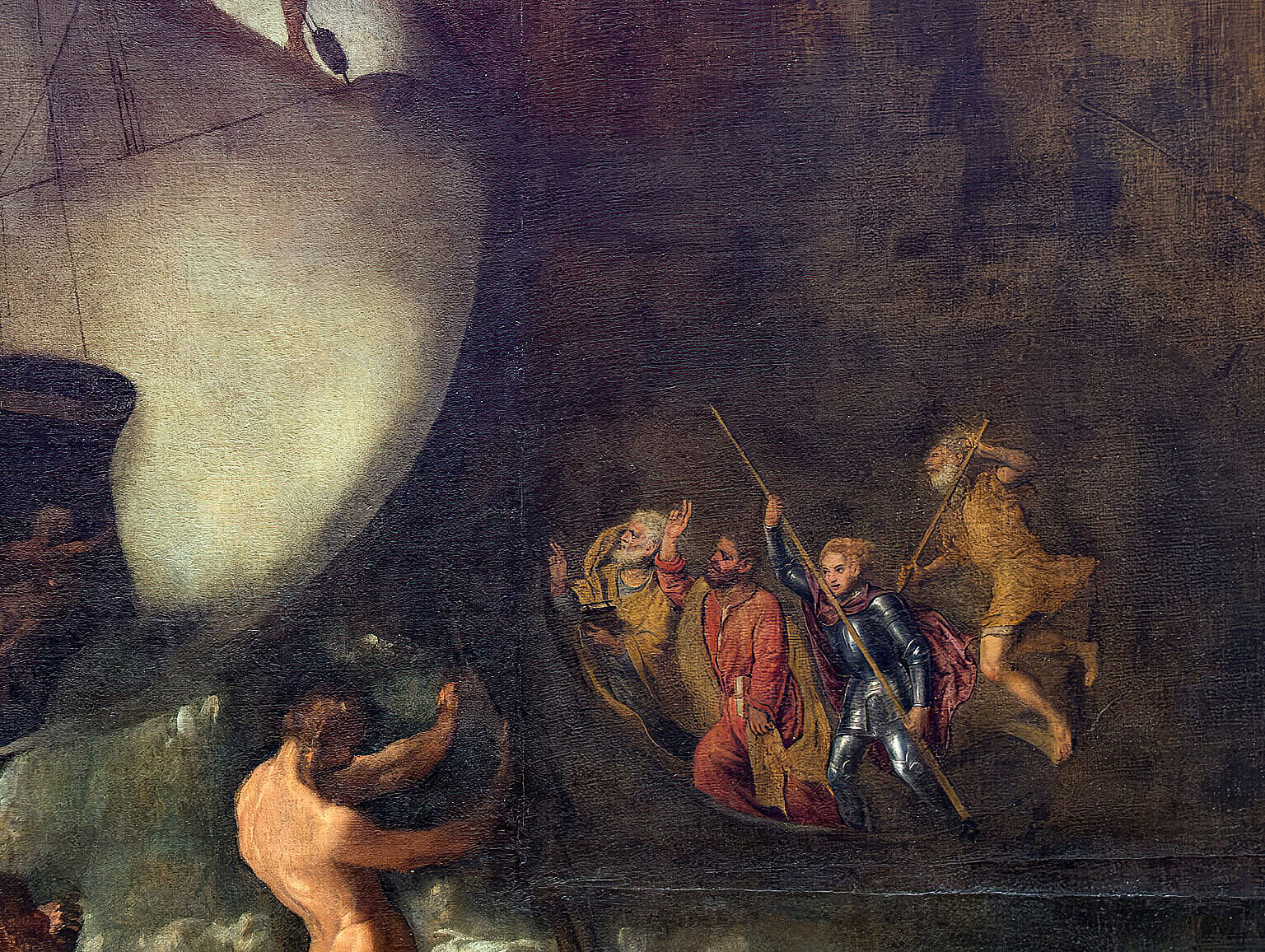

That was (mostly) by Jacopo Palma il Vecchio, from around 1528, called Burrasca di mare — Storm at Sea — or “Saints Mark, George and Nicholas Freeing Venice from Demons.”

The painting was commissioned from Giovanni Mansueti, who had done another painting of St Mark for the school, but he died in 1527, and the job passed to Jacopo Palma il Vecchio, who in turn died in 1528, leaving the painting unfinished. That is probably why the upper right looks incomplete.

The boat with the three saints and the old fisherman was likely added later by Paris Borbone to fill the empty space in the unfinished painting, and make the story more recognisable.

Both of these paintings are now in the Galleria dell’Accademia, which resides in another of the ancient Scuole Grandi of Venice — the Scuola Grande della Carità.

The legend is now mostly forgotten, because it is no longer part of anybody’s narrative.

Related articles

Bibliography

Tassini, Giuseppe. Curiosità Veneziane ovvero Origini delle denominazioni stradali di Venezia. 1863.