John Evelyn (1620-1706) was an English gentleman, royalist, who travelled Europe for much of the 1640s, probably trying to stay clear of the English civil war. During his travels, he stayed in Venice and Padua for much of 1645 and 1646.

He kept a detailed diary for most of his life, which was published only in the 1800s. This is an extract from his published diary: Evelyn (1850), p. 195–218.

My notes and comments are in the footnotes. Besides the notes, the text is as is.

We parted from hence about three in the afternoon, and went some of our way on the canal, and then embarked on the Po, or Padus, by the poets called Eridanus, where they feign Phæton to have fallen after his rash attempt, and where Io was metamorphosed into a cow. There was in our company, amongst others, a Polonian Bishop, who was exceeding civil to me in this passage, and afterwards did me many kindnesses at Venice. We supped this night at a place called Corbua, near the ruins of the ancient city, Adria, which gives name to the Gulf, or Sea. After three miles, having passed thirty on the Po, we embarked in a stout vessel, and through an artificial canal, very straight, we entered the Adige, which carried us by break of day into the Adriatic, and so sailing prosperously by Chioza1 (a town upon an island in this sea,) and Palestina,2 we came over against Malamocco3 (the chief port and anchorage where our English merchantmen lie that trade to Venice) about seven at night, after we had stayed at least two hours for permission to land, our bill of health being delivered,4 according to custom. So soon as we came on shore, we were conducted to the Dogana,5 where our portmanteaus were visited, and then we got to our lodging, which was at honest Signor Paulo Rhodomante’s at the Black Eagle,6 near the Rialto, one of the best quarters of the town. This journey from Rome to Venice cost me seven pistoles, and thirteen julios.

June. The next morning, finding myself extremely weary and beaten with my journey, I went to one of their bagnios, where you are treated after the eastern manner, washing with hot and cold water, with oils, and being rubbed with a kind of strigil of seal’s-skin, put on the operator’s hand like a glove. This bath did so open my pores, that it cost me one of the greatest colds I ever had in my life, for want of necessary caution in keeping myself warm for some time after ; for, coming out, I immediately began to visit the famous places of the city ; and travellers who come into Italy do nothing but run up and down to see sights, and this city well deserved our admiration, being the most wonderfully placed of any in the world, built on so many hundred islands, in the very sea, and at good distance from the continent. It has no fresh water, except what is reserved in cisterns from rain, and such as is daily brought from terra firma in boats, yet there was no want of it, and all sorts of excellent provisions were very cheap.

It is said that when the Huns over-ran Italy some mean fishermen and others left the main land, and fled for shelter to these despicable and muddy islands,7 which, in process of time, by industry, are grown to the greatness of one of the most considerable States, considered as a Republic, and having now subsisted longer than any of the four ancient Monarchies, flourishing in great state, wealth, and glory, by the conquest of great territories in Italy, Dacia, Greece, Candia,8 Rhodes, and Sclavonia,9 and at present challenging the empire of all the Adriatic Sea, which they yearly espouse by casting a gold ring into it with great pomp and ceremony,10 on Ascension-day ; the desire of seeing this, was one of the reasons that hastened us from Rome.

The Doge, having heard mass in his robes of state (which are very particular, after the eastern fashion), together with the Senate in their gowns, embarked in their gloriously painted, carved, and gilded Bucentora,11 environed and followed by innumerable galleys, gondolas, and boats, filled with spectators, some dressed in masquerade, trumpets, music, and cannons. Having rowed about a league into the Gulf, the Duke, at the prow, casts a gold ring and cup into the sea, at which a loud acclamation is echoed from the great guns of the Arsenal, and at the Liddo.12 We then returned.

Two days after, taking a gondola, which is their watercoach (for land ones there are many old men in this city who never saw one, or rarely a horse), we rowed up and down the channels, which answer to our streets. These vessels are built very long and narrow, having necks and tails of steel, somewhat spreading at the beak like a fish’s tail, and kept so exceedingly polished as to give a great lustre ; some are adorned with carving, others lined with velvet, (commonly black), with curtains and tassels, and the seats like couches, to be stretched on, while he who rows, stands upright on the very edge of the boat, and, with one oar bending forward as if he would fall into the sea, rows and turns with incredible dexterity ; thus passing from channel to channel, landing his fare, or patron, at what house he pleases. The beaks of these vessels are not unlike the ancient Roman rostrums.13

The first public building I went to see, was the Rialto, a bridge of one arch over the grand canal, so large as to admit a galley to row under it, built of good marble, and having on it, besides many pretty shops, three ample and stately passages for people without any inconvenience, the two outmost nobly balustred with the same stone ; a piece of architecture much to be admired. It was evening, and the canal where the Noblesse go to take the air, as in our Hyde-park, was full of ladies and gentlemen. There are many times dangerous stops, by reason of the multitude of gondolas ready to sink one another ; and indeed they affect to lean them on one side, that one who is not accustomed to it, would be afraid of over-setting. Here they were singing, playing on harpsichords, and other music, and serenading their mistresses ; in another place, racing, and other pastimes on the water, it being now exceeding hot.

Next day, I went to their Exchange,14 a place like ours, frequented by merchants, but nothing so magnificent: from thence, my guide led me to the Fondigo di Todeschi,15 which is their magazine, and here many of the merchants, especially Germans, have their lodging and diet as in a college. The outside of this stately fabric is painted by Giorgione da Castelfranco, and Titian himself.16

Hence, I passed through the Mercera,17 one of the most delicious streets in the world for the sweetness of it, and is all the way on both sides tapestried as it were with cloth of gold, rich damasks and other silks, which the shops expose and hang before their houses from the first floor, and with that variety that for near half the year spent chiefly in this city, I hardly remember to have seen the same piece twice exposed ; to this add the perfumes, apothecaries’ shops, and the innumerable cages of nightingales which they keep,18 that entertain you with their melody from shop to shop, so that shutting your eyes you would imagine yourself in the country, when indeed you are in the middle of the sea. It is almost as silent as the middle of a field, there being neither rattling of coaches nor trampling of horses. This street, paved with brick, and exceedingly clean, brought us through an arch into the famous piazza of St. Mark.

Over this porch, stands that admirable Clock, celebrated next to that of Strasburg for its many movements ; amongst which, about twelve and six, which are their hours of Ave Maria, when all the town are on their knees, come forth the three Kings led by a star, and passing by the image of Christ in his Mother’s arms, do their reverence, and enter into the clock by another door. At the top of this turret, another automaton strikes the quarters. An honest merchant told me that one day, walking in the piazza, he saw the fellow who kept the clock struck with this hammer so forcibly, as he was stooping his head near the bell to mend something amiss at the instant of striking, that being stunned he reeled over the battlements, and broke his neck. The buildings in this piazza are all arched, on pillars, paved within with black and white polished marble, even to the shops, the rest of the fabric as stately as any in Europe, being not only marble, but the architecture is of the famous Sansovini, who lies buried in St. Jacomo,19 at the end of the piazza. The battlements of this noble range of building are railed with stone, and thick-set with excellent statues, which add a great ornament. One of the sides is yet much more Roman-like than the other which regards the sea, and where the church is placed. The other range is plainly Gothic : and so we entered into St. Mark’s Church, before which stand two brass pedestals exquisitely cast and figured,20 which bear as many tall masts painted red, on which upon great festivals they hang flags and streamers. The church is also Gothic; yet for the preciousness of the materials, being of several rich marbles, abundance of porphyry, serpentine, &c., far exceeding any in Rome, St. Peter’s hardly excepted. I much admired the splendid history of our blessed Saviour composed all of mosaic over the facciata, below which and over the chief gate are cast four horses in copper as big as the life, the same that formerly were transported from Rome by Constantino to Byzantium, and thence by the Venetians hither. They are supported by eight porphyry columns, of very great size and value. Being come into the Church, you see nothing, and tread on nothing, but what is precious. The floor is all inlaid with agates, lazulis, chalcedons, jaspers, porphyries, and other rich marbles, admirable also for the work ; the walls sumptuously incrusted, and presenting to the imagination the shapes of men, birds, houses, flowers, and a thousand varieties. The roof is of most excellent mosaic ; but what most persons admire is the new work of the emblematic tree at the other passage out of the church. In the midst of this rich volto rise five cupolas, the middle very large and sustained by thirty-six marble columns, eight of which are of precious marbles : under these cupolas is the high altar, on which is a reliquary of several sorts of jewels, engraven with figures, after the Greek manner, and set together with plates of pure gold. The altar is covered with a canopy of ophite, on which is sculptured the story of the Bible, and so on the pillars, which are of Parian marble, that support it. Behind these, are four other columns of transparent and true oriental alabaster, brought hither out of the mines of Solomon’s Temple, as they report. There are many chapels and notable monuments of illustrious persons, dukes, cardinals, &c., as Zeno, J. Soranzi, and others : there is likewise a vast baptistery, of copper. Among other venerable relics is a stone, on which they say our blessed Lord stood preaching to those of Tyre and Sidon, and near the door is an image of Christ, much adored, esteeming it very sacred, for that a rude fellow striking it, they say, there gushed out a torrent of blood. In one of the corners lies the body of St. Isidore, brought hither 500 years since from the island of Chios. A little farther, they show the picture of St. Dominic and Francis, affirmed to have been made by the Abbot Joachim (many years before any of them were born). Going out of the Church, they showed us the stone where Alexander III. trod on the neck of the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, pronouncing that verse of the psalm, ” super basiliscum, ” &c. The doors of the Church are of massy copper. There are near 500 pillars in this building, most of them porphyry and serpentine, and brought chiefly from Athens, and other parts of Greece, formerly in their power. At the corner of the Church, are inserted into the main wall four figures, as big as life, cut in porphyry, which they say are the images of four brothers who poisoned one another, by which means there escheated to the Republic that vast treasury of relics now belonging to the Church. At the other entrance that looks towards the sea, stands in a small chapel that statue of our Lady, made (as they affirm) of the same stone, or rock, out of which Moses brought water to the murmuring Israelites at Horeb, or Meriba.

After all that is said, this church is, in my opinion, much too dark and dismal, and of heavy work ; the fabric, as is much of Venice, both for buildings and other fashions and circumstances, after the Greeks, their next neighbours.

The next day, by favour of the French Ambassador, I had admittance with him to view the Reliquary, called here Tesoro di San Marco, which very few, even of travellers, are admitted to see. It is a large chamber full of presses. There are twelve breast-plates, or pieces of pure golden armour, studded with precious stones, and as many crowns dedicated to St. Mark by so many noble Venetians, who had recovered their wives taken at sea by the Saracens ; many curious vases of agates ; the cap, or coronet, of the Dukes of Venice, one of which had a ruby set on it, esteemed worth 200,000 crowns; two unicorns’ horns; numerous vases and dishes of agate, set thick with precious stones and vast pearls ; divers heads of Saints, enchased in gold ; a small ampulla, or glass, with our Saviour’s blood ; a great morsel of the real cross ; one of the nails ; a thorn ; a fragment of the column to which our Lord was bound, when scourged; the standard, or ensign, of Constantine ; a piece of St. Luke’s arm ; a rib of St. Stephen ; a finger of Mary Magdalene ; numerous other things, which I could not remember ; but a priest, first vesting himself in his sacerdotals, with the stole about his neck, showed us the Gospel of St. Mark (their tutelar patron) written by his own hand, and whose body they show buried in the church, brought hither from Alexandria many years ago.

The Religious de li Servi have fine paintings of Paolo Veronese, especially the Magdalen.21

A French gentleman and myself went to the Courts of Justice, the Senate-house, and Ducal Palace. The first court near this church is almost wholly built of several coloured sorts of marble, like chequer-work on the outside; this is sustained by vast pillars, not very shapely, but observable for their capitals, and that out of thirty-three no two are alike. Under this fabric is the cloister where merchants meet morning and evening, as also the grave senators and gentlemen, to confer of state-affairs, in their gowns and caps, like so many philosophers ; it is a very noble and solemn spectacle. In another quadrangle, stood two square columns of white marble, carved, which they said had been erected to hang one of their Dukes on, who designed to make himself Sovereign. Going through a stately arch, there were standing in niches divers statues of great value, amongst which is the so celebrated Eve, esteemed worth its weight in gold ; it is just opposite to the stairs where are two Colossuses of Mars and Neptune, by Sansovino. We went up into a Corridor built with several Tribunals and Courts of Justice ; and by a well-contrived staircase were landed in the Senate-hall,22 which appears to be one of the most noble and spacious rooms in Europe, being seventy-six paces long, and thirty-two in breadth. At the upper end, are the Tribunals of the Doge, Council of Ten, and Assistants ; in the body of the hall, are lower ranks of seats, capable of containing 1500 Senators ; for they consist of no fewer on grand debates. Over the Duke’s throne are the paintings of the Final Judgment, by Tintoret, esteemed amongst the best pieces in Europe. On the roof are the famous Acts of the Republic, painted by several excellent masters, especially Bassano ; next them, are the effigies of the several Dukes, with their Elogies. Then, we turned into a great Court painted with the Battle of Lepanto,23 an excellent piece ; afterwards, into the Chamber of the Council of Ten, painted by the most celebrated masters. From hence, by the special favour of an Illustrissimo, we were carried to see the private Armoury of the Palace,24 and so to the same Court we first entered, nobly built of polished white marble, part of which is the Duke’s Court, pro tempore; there are two wells adorned with excellent work, in copper. This led us to the sea-side, where stand those columns of ophite-stone in the entire piece, of a great height, one bearing St. Mark’s Lion, the other St. Theodorus ; these pillars were brought from Greece, and set up by Nicholas Baraterius, the architect ; between them public executions are performed.

Having fed our eyes with the noble prospect of the Island of St. George, the galleys, gondolas, and other vessels passing to and fro, we walked under the cloister on the other side of this goodly piazza, being a most magnificent building, the design of Sansovino. Here we went into the Zecca, or Mint ; at the entrance, stand two prodigious giants, or Hercules, of white marble : we saw them melt, beat, and coin silver, gold, and copper. We then went up into the Procuratory, and a library of excellent MSS, and books belonging to it and the public. After this, we climbed up the tower of St. Mark, which we might have done on horseback, as it is said one of the French Kings did, there being no stairs, or steps, but returns that take up an entire square on the arches forty feet, broad enough for a coach.25 This steeple stands by itself, without any church near it, and is rather a watch tower in the corner of the great piazza, 230 feet in height, the foundation exceeding deep ; on the top, is an angel, that turns with the wind; and from hence is a prospect down the Adriatic, as far as Istria and the Dalmatian side, with the surprising sight of this miraculous city, lying in the bosom of the sea, in the shape of a lute, the numberless Islands tacked together by no fewer than 450 bridges. At the foot of this tower, is a public tribunal of excellent work, in white marble polished, adorned with several brass statues and figures of stone in mezzo-relievo, the performance of some rare artist.

It was now Ascension-Week, and the great mart, or fair, of the whole year was kept, every body at liberty and jolly. The noblemen stalking with their ladies on choppines26 ; these are high-heeled shoes, particularly affected by these proud dames, or, as some say, invented to keep them at home, it being very difficult to walk with them ; whence one being asked how he liked the Venetian dames, replied, they were mezzo carne, mezzo legno, half flesh, half wood ; and he would have none of them. The truth is, their garb is very odd, as seeming always in masquerade; their other habits also totally different from all nations. They wear very long crisp hair, of several streaks and colours, which they make so by a wash, dishevelling it on the brims of a broad hat that has no crown, but a hole to put out their heads by ; they dry them in the sun, as one may see them at their windows. In their tire, they set silk flowers and sparkling stones, their petticoats coming from their very arm-pits, so that they are near three quarters and a half apron ; their sleeves are made exceeding wide, under which their shift- sleeves as wide, and commonly tucked up to the shoulder, showing their naked arms, through false sleeves of tiffany,27 girt with a bracelet or two, with knots of points richly tagged about their shoulders and other places of their body, which they usually cover with a kind of yellow veil, of lawn, very transparent. Thus attired, they set their hands on the heads of two matron-like servants, or old women, to support them, who are mumbling their beads. It is ridiculous to see how these ladies crawl in and out of their gondolas, by reason of their choppines, and what dwarfs they appear, when taken down from their wooden scaffolds; of these, I saw near thirty together, stalking half as high again as the rest of the world; for courtezans,28 or the citizens,29 may not wear choppines, but cover their bodies and faces with a veil of a certain glittering taffeta,30 or lustrée, out of which they now and then dart a glance of their eye, the whole face being otherwise entirely hid with it ; nor may the common misses take this habit ; but go abroad barefaced. To the corners of these virgin-veils hang broad but flat tassels of curious Point de Venice.31 The married women go in black veils. The nobility32 wear the same colour, but of fine cloth lined with taffeta, in summer, with fur of the bellies of squirrels,33 in the winter, which all put on at a certain day girt with a girdle embossed with silver ; the vest not much different from what our Bachelors of Arts wear in Oxford, and a hood of cloth, made like a sack, cast over their left shoulder, and a round cloth black cap fringed with wool, which is not so comely ; they also wear their collar open, to show the diamond button of the stock of their shirt. I have never seen pearl for colour and bigness comparable to what the ladies wear, most of the noble families being very rich in jewels, especially pearls, which are always left to the son, or brother, who is destined to marry ; which the eldest seldom do. The Doge’s vest is of crimson velvet, the Procurator’s,34 &c. of damask, very stately. Nor was I less surprised with the strange variety of the several nations seen every day in the streets and piazzas ; Jews, Turks, Armenians, Persians, Moors,35 Greeks, Sclavonians,36 some with their targets and bucklers, and all in their native fashions, negociating in this famous Emporium,37 which is always crowded with strangers.

This night, having with my Lord Bruce taken our places before, we went to the Opera, where comedies and other plays are represented in recitative music, by the most excellent musicians, vocal and instrumental, with variety of scenes painted and contrived with no less art of perspective, and machines for flying in the air, and other wonderful motions ; taken together, it is one of the most magnificent and expensive diversions the wit of man can invent.38 The history was, Hercules in Lydia; the scenes changed thirteen times.39 The famous voices Anna Rencia,40 a Roman, and reputed the best treble of women; but there was an eunuch41 who, in my opinion, surpassed her ; also a Genoese that sung an incomparable base. This held us by the eyes and ears till two in the morning, when we went to the Chetto de san Felice,42 to see the noblemen and their ladies at basset, a game at cards which is much used; but they play not in public, and all that have inclination to it are in masquerade, without speaking one word, and so they come in, play, lose, or gain, and go away as they please. This time of licence is only in Carnival and this Ascension-Week ; neither are their theatres open for that other magnificence, or for ordinary comedians, save on these solemnities, they being a frugal and wise people, and exact observers of all sumptuary laws.

There being at this time a ship bound for the Holy Land, I had resolved to embark, intending to see Jerusalem, and other parts of Syria, Egypt, and Turkey ; but, after I had provided all necessaries, laid in snow to cool our drink, bought some sheep, poultry, biscuit, spirits, and a little cabinet of drugs, in case of sickness, our vessel (whereof Captain Powell was master) happened to be pressed for the service of the State, to carry provisions to Candia,43 now newly attacked by the Turks ; which altogether frustrated my design, to my great mortification.

On the . . . June, we went to Padua, to the Fair of their St. Anthony, in company of divers passengers. The first terra firma we landed at, was Fusina, being only an inn, where we changed our barge, and were then drawn up by horses through the river Brenta, a straight channel as even as a line for twenty miles, the country on both sides deliciously adorned with country villas and gentlemen’s retirements, gardens planted with oranges, figs, and other fruit, belonging to the Venetians. At one of these villas, we went ashore to see a pretty contrived palace. Observable in this passage was buying their water of those who farm the sluices ; for this artificial river is in some places so shallow, that reserves of water are kept with sluices, which they open and shut with a most ingenious invention, or engine, governed even by a child. Thus they keep up the water, or let it go, till the next channel be either filled by the stop, or abated to the level of the other ; for which every boat pays a certain duty. Thus, we stayed near half an hour and more, at three several places, so as it was evening before we got to Padua. This is a very ancient city, if the tradition of Antenor’s being the founder be not a fiction; but thus speaks the inscription over a stately gate :

Hanc antiquissimam urbem literarum omnium asylum, cujus agrum fertilitatis Lumen Natura esse voluit, Antenor condidit anno ante Christum natum M.Cxviii ; Senatus autem Venetus his belli propugnaculis ornavit.

The town stands on the river Padus, whence its name, and is generally built like Bologna, on arches and on brick, so that one may walk all round it, dry, and in the shade ; which is very convenient in these hot countries, and I think I was never sensible of so burning a heat as I was this season, especially the next day, which was that of the fair, filled with noble Venetians, by reason of a great and solemn procession to their famous cathedral. Passing by St. Lorenzo, I met with this subscription :

Inclytus Antenor patriam vox nisa quietem

Transtulit hue Henetum Dardanidumq ; fuga,

Expulit Euganeos, Patavinam condidit urbem,

Quern tegit hic humili marmore cæsa domus.

Under the tomb, was a cobbler at his work. Being now come to St. Antony’s (the street most of the way straight, well-built, and outsides excellently painted in fresco) we surveyed the spacious piazza, in which is erected a noble statue of copper of a man on horseback, in memory of one Catta Malata, a renowned captain. The church, a la Greca, consists of five handsome cupolas, leaded. At the left hand within, is the tomb of St. Antony and his altar, about which a mezzo-relievo of the miracles ascribed to him is exquisitely wrought in white marble by the three famous sculptors, Tullius Lombardus, Jacobus Sansovinus, and Hieronymus Compagno. A little higher is the choir, walled parapet-fashion, with sundry coloured stone, half relievo, the work of Andrea Reccij. The altar within is of the same metal which, with the candlestick and bases, is, in my opinion, as magnificent as any in Italy. The wainscot of the choir is rarely inlaid and carved. Here are the sepulchres of many famous persons, as of Rodolphus Fulgosi, &c. ; and, among the rest, one for an exploit at sea, has a galley exquisitely carved thereon. The procession bore the banners with all the treasure of the cloister, which was a very fine sight.

Hence, walking over the Prato delle Valle, I went to see the convent of St. Justina, than which I never beheld one more magnificent. The church is an excellent piece of architecture, of Andrea Palladio, richly paved, with a stately cupola that covers the high altar enshrining the ashes of that saint. It is of pietra-commessa, consisting of flowers very naturally done. The choir is inlaid with several sorts of wood representing the holy history, finished with exceeding industry. At the far end, is that rare painting of St. Justina’s Martyrdom, by Paolo Veronese ; and a stone on which they told us divers primitive Christians had been decapitated. In another place (to which leads a small cloister well-painted) is a dry well, covered with a brass-work grate, wherein are the bones of divers martyrs. They show also the bones of St. Luke, in an old alabaster coffin ; three of the Holy Innocents ; and the bodies of St. Maximus and Prosdocimus. The dormitory above is exceeding commodious and stately; but, what most pleased me, was the old cloister so well painted with the legendary saints, mingled with many ancient inscriptions, and pieces of urns dug up, it seems, at the foundation of the church. Thus, having spent the day in rambles, I returned the next day to Venice.

The arsenal is thought to be one of the best-furnished in the world. We entered by a strong port, always guarded, and, ascending a spacious gallery, saw arms of back, breast, and head, for many thousands ; in another, were saddles ; over them, ensigns taken from the Turks. Another hall is for the meeting of the Senate ; passing a graff, are the smiths’ forges, where they are continually employed on anchors and iron work. Near it is a well of fresh water, which they impute to two rhinoceros’s horns which they say lie in it, and will preserve it from ever being empoisoned. Then we came to where the carpenters were building their magazines of oars, masts, &c., for an hundred galleys and ships, which have all their apparel and furniture near them. Then the foundery, where they cast ordnance; the forge is 450 paces long, and one of them has thirteen furnaces. There is one cannon weighing 16,573 lbs., cast whilst Henry the Third dined, and put into a galley built, rigged, and fitted for launching within that time. They have also arms for twelve galeasses, which are vessels to row, of almost 150 feet long and thirty wide, not counting prow, or poop, and contain twenty-eight banks of oars, each seven men, and to carry 1300 men, with three masts. In another, a magazine for fifty galleys, and place for some hundreds more. Here stands the Bucentaur, with a most ample deck, and so contrived that the slaves are not seen,44 having on the poop a throne for the Doge to sit, when he goes in triumph to espouse the Adriatic. Here is also a gallery of 200 yards long for cables,45 and above that a magazine of hemp. Opposite these, are the saltpetre houses,46 and a large row of cells, or houses, to protect their galleys from the weather. Over the gate, as we go out, is a room full of great and small guns, some of which discharge six times at once. Then, there is a court full of cannon, bullets, chains, grapples, grenadoes, &c,, and over that arms for 800,000 men, and by themselves arms for 400, taken from some that were in a plot against the State ; together with weapons of offence and defence for sixty-two ships ; thirty-two pieces of ordnance, on carriages taken from the Turks, and one prodigious mortar-piece. In a word, it is not to be reckoned up what this large place contains of this sort. There were now twenty-three galleys, and four gallygrossi, of 100 oars of a side. The whole arsenal is walled about, and may be in compass about three miles, with twelve towers for the watch, besides that the sea environs it. The workmen, who are ordinarily 500, march out in military order, and every evening receive their pay through a small hole in the gate where the governor lives.

The next day, I saw a wretch executed, who had murdered his master, for which he had his head chopped off by an axe that slid down a frame of timber,47 between the two tall columns in St. Mark’s piazza, at the sea-brink; the executioner striking on the axe with a beetle ; and so the head fell off the block.

Hence, by Gudala, we went to see Grimani’s Palace,48 the portico whereof is excellent work. Indeed, the world cannot show a city of more stately buildings, considering the extent of it, all of square stone, and as chargeable in their foundations, as superstructure, being all built on piles at an immense cost. We returned home by the church of St. Johanne and Paulo,49 before which is, in copper, the statue of Bartolomeo Colone,50 on horseback, double gilt, on a stately pedestal, the work of Andrea Verrochio, a Florentine ! This is a very fine church, and has in it many rare altar-pieces of the best masters, especially that on the left hand, of the Two Friars slain, which is of Titian.

The day after, being Sunday, I went over to St. George’s to the ceremony of the schismatic Greeks,51 who are permitted to have their church, though they are at defiance with Rome. They allow no carved images, but many painted, especially the story of their patron and his dragon. Their rites differ not much from the Latins, save that of communicating in both species, and distribution of the holy bread. We afterwards fell into a dispute with a Candiot,52 concerning the procession of the Holy Ghost. The church is a noble fabric.

The church of St. Zachary is of Greek building, by Leo IV. Emperor, and has in it the bones of that prophet, with divers other saints. Near this, we visited St. Luke’s, famous for the tomb of Aretin.53

Tuesday, we visited several other churches, as Santa Maria,54 newly incrusted with marble on the outside, and adorned with porphyry, ophite, and Spartan stone. Near the altar and under the organ, are sculptures, that are said to be of the famous artist, Praxiteles. To that of St. Paul55 I went purposely, to see the tomb of Titian. Then to St. John the Evangelist,56 where, amongst other heroes, lies Andrea Baldarius, the inventor of oars applied to great vessels for fighting.

We also saw St. Roche,57 the roof whereof is, with the school, or hall, of that rich confraternity, admirably painted by Tintoretto, especially the Crucifix in the sacristia. We saw also the church of St. Sebastian, and Carmelites’ monastery.

Next day, taking our gondola at St. Mark’s, I passed to the island of St. George Maggiore, where is a Convent of Benedictines, and a well-built church of Andrea Palladio, the great architect. The pavement, cupola, choir, and pictures, very rich and sumptuous. The cloister has a fine garden to it, which is a rare thing at Venice, though this is an island a little distant from the city ; it has also an olive-orchard, all environed by the sea. The new cloister now building has a noble stair-case paved with white and black marble.

From hence, we visited St. Spirit58o and St. Laurence,59 fair churches in several islands ; but most remarkable is that of the Padri Olivetani, in St. Helen’s island,60 for the rare paintings and carvings, with inlaid work, &c.

The next morning, we went again to Padua, where, on the following day, we visited the market, which is plentifully furnished, and exceedingly cheap. Here we saw the great hall, built in a spacious piazza, and one of the most magnificent in Europe ; its ascent is by steps a good height, of a reddish marble polished, much used in these parts, and happily found not far off; it is almost 200 paces long, and forty in breadth, all covered with lead, without any support of columns. At the farther end, stands the bust, in white marble, of Titus Livius, the historian. In this town is the house wherein he was born, full of inscriptions and pretty fair.

Near to the monument of Speron Speroni, is painted on the ceiling the celestial zodiac, and other astronomical figures ; without side, there is a corridor, in manner of a balcony, of the same stone ; and at the entry of each of the three gates is the head of some famous person, as Albert Eremitano, Julio Paullo (lawyers), and Peter Aponius. In the piazza is the Podestà’s and Capitano Grande’s Palace, well-built ; but, above all, the Monte Pietà, the front whereof is of most excellent architecture. This is a foundation of which there is one in most of the cities in Italy, where there is a continual bank of money to assist the poorer sort, on any pawn, and at reasonable interest, together with magazines for deposit of goods, till redeemed.

Hence, to the Schools of this flourishing and ancient University, especially for the study of physic and anatomy. They are fairly built in quadrangle, with cloisters beneath, and above with columns. Over the great gate are the arms of the Venetian State, and under the lion of St. Mark:

Sic ingredere, ut teipso quotidie doctior ; sic egredere ut indies Patriae Christiansæq ; Republicæ utilior evadas ; ita demùm Gymnasium à te felicitèr se ornatum existimabit.

CIꜾ.IX.

About the court-walls, are carved in stone and painted the blazons of the Consuls of all the nations, that from time to time have had that charge and honour in the University, which at my being there was my worthy friend Dr. Rogers, who here took that degree.

The Schools for the lectures of the several sciences are above, but none of them comparable, or so much frequented, as the theatre for anatomy, which is excellently contrived both for the dissector and spectators. I was this day invited to dinner, and, in the afternoon, (30th July) received my matricula, being resolved to spend some months here at study, especially physic and anatomy, of both which there were now the most famous professors in Europe. My matricula contained a clause, that I, my goods, servants, and messengers, should be free from all tolls and reprises, and that we might come, pass, return, buy, or sell, without any toll, &c.

The next morning, I saw the garden of simples, rarely furnished with plants, and gave order to the gardener to make me a collection of them for an hortus hyemalis, by permission of the Cavalier Dr. Veslingius, then Prefect and Botanic Professor as well as of Anatomy.

This morning, the Earl of Arundel, now in this city, a famous collector of paintings and antiquities, invited me to go with him to see the garden of Mantua, where, as one enters, stands a huge colosse of Hercules. From hence to a place where was a room covered with a noble cupola, built purposely for music ; the fillings up, or cove, betwixt the walls, were of urns and earthen pots, for the better sounding; it was also well-painted. After dinner, we walked to the Palace of Foscari all’ Arena, there remaining yet some appearances of an ancient theatre, though serving now for a court only before the house. There were now kept in it two eagles, a crane, a Mauritanian sheep, a stag, and sundry fowls, as in a vivary.

Three days after, I returned to Venice, and passed over to Murano, famous for the best glasses in the world, where having viewed their furnaces and seen their work, I made a collection of divers curiosities and glasses, which I sent for England by long sea. It is the white flints they have from Pavia, which they pound and sift exceedingly small, and mix with ashes made of a sea-weed brought out of Syria, and a white sand, that causes this manufacture to excel. The town is a Podestaria by itself,61 at some miles distant on the sea from Venice, and like it built upon several small islands. In this place, are excellent oysters, small and well-tasted like our Colchester, and they were the first, as I remember, that I ever could eat ; for I had naturally an aversion to them.

At our return to Venice, we met several gondolas full of Venetian ladies, who come thus far in fine weather to take the air, with music and other refreshments. Besides that, Murano is itself a very nobly built town, and has divers noblemen’s palaces in it, and handsome gardens.

In coming back, we saw the islands of St. Christopher and St. Michael,62 the last of which has a church enriched and incrusted with marbles and other architectonic ornaments, which the monks very courteously showed us. It was built and founded by Margaret Emiliana of Verona, a famous courtezan, who purchased a great estate, and by this foundation hoped to commute for her sins.63 We then rowed by the isles of St. Nicholas, whose church, with the monuments of the Justinian family,64 entertained us awhile : and then got home.

The next morning, Captain Powell, in whose ship I was to embark towards Turkey, invited me on board, lying about ten miles from Venice, where we had a dinner of English powdered beef and other good meat, with store of wine and great guns, as the manner is. After dinner, the Captain presented me with a stone he had lately brought from Grand Cairo, which he took from the mummy-pits, full of hieroglyphics ; I drew it on paper with the true dimensions, and sent it in a letter to Mr. Henshaw to communicate to Father Kircher, who was then setting forth his great work ” Obeliscus Pamphilius,” where it is described, but without mentioning my name. The stone was afterwards brought for me into England, and landed at Wapping, where, before I could hear of it, it was broken into several fragments, and utterly defaced, to my no small disappointment.

The boatswain of the ship also gave me a hand and foot of a mummy, the nails whereof had been overlaid with thin plates of gold, and the whole body was perfect, when he brought it out of Egypt ; but the avarice of the ship’s crew broke it to pieces, and divided the body among them. He presented me also with two Egyptian idols, and some loaves of the bread which the Coptics use in the holy Sacrament, with other curiosities.

8th August. I had news from Padua of my election to be Syndicus Artisiarum, which caused me, after two days’ idling in a country villa with the Consul of Venice, to hasten thither, that I might discharge myself of that honour, because it was not only chargeable, but would have hindered my progress, and they chose a Dutch gentleman in my place, which did not well please my countrymen, who had laboured not a little to do me the greatest honour a stranger is capable of in that University. Being freed from this impediment, and having taken leave of Dr. Janicius, a Polonian, who was going physician in the Venetian galleys to Candia, I went again to Venice, and made a collection of several books and some toys. Three days after, I returned to Padua, where I studied hard till the arrival of Mr. Henshaw, Bramstone, and some other English gentlemen whom I had left at Rome, and who made me go back to Venice, where I spent some time in showing them what I had seen there.

26th September. My dear friend, and till now my constant fellow-traveller, Mr. Thicknesse, being obliged to return to England upon his particular concern, and who had served his Majesty in the wars, I accompanied him part of his way, and, on the 28th, returned to Venice.

29th. Michaelmas-day, I went with my Lord Mowbray (eldest son to the Earl of Arundel, and a most worthy person) to see the collection of a noble Venetian, Signor Rugini.65 He has a stately Palace, richly furnished with statues and heads of Roman Emperors, all placed in an ample room. In the next, was a cabinet of medals, both Latin and Greek, with divers curious shells and two fair pearls in two of them ; but, above all, he abounded in things petrified, walnuts, eggs in which the yolk rattled ; a pear, a piece of beef with the bones in it, a whole hedgehog, a plaice on a wooden trencher turned into stone and very perfect, charcoal, a morsel of cork yet retaining its levity, sponges, and a piece of taffety, part rolled up, with innumerable more. In another cabinet, supported by twelve pillars of oriental agate, and railed about with crystal, he showed us several noble intáglios of agate, especially a head of Tiberius, a woman in a bath with her dog, some rare cornelians, onyxes, crystals, &c., in one of which was a drop of water not congealed, but moving up and down, when shaken ; above all, a diamond which had a very fair ruby growing in it; divers pieces of amber, wherein were several insects, in particular one cut like a heart that contained in it a salamander without the least defect, and many pieces of mosaic. The fabric of this cabinet was very ingenious, set thick with agates, turquoises, and other precious stones, in the midst of which was an antique of a dog in stone scratching his ear, very rarely cut, and comparable to the greatest curiosity I had ever seen of that kind for the accurateness of the work. The next chamber had a bedstead all inlaid with agates, crystals, cornelians, lazuli, &c., esteemed worth 16,000 crowns ; but, for the most part, the bedsteads in Italy are of forged iron gilded, since it is impossible to keep the wooden ones from the cimices.

From hence, I returned to Padua, when that town was so infested with soldiers, that many houses were broken open in the night, some murders committed, and the nuns next our lodging disturbed, so as we were forced to be on our guard with pistols and other fire-arms to defend our doors ; and indeed the students themselves take a barbarous liberty in the evenings when they go to their strumpets, to stop all that pass by the house where any of their companions in folly are with them. This custom they call chi vali, so as the streets are very dangerous, when the evenings grow dark ; nor is it easy to reform this intolerable usage, where there are so many strangers of several nations.

Using to drink my wine cooled with snow and ice, as the manner here is, I was so afflicted with an angina and sore-throat, that it had almost cost me my life. After all the remedies Cavalier Veslingius, chief professor here, could apply, old Salvatico (that famous physician) being called, made me be cupped, and scarified in the back in four places ; which began to give me breath, and consequently life; for I was in the utmost danger; but, God being merciful to me, I was after a fortnight abroad again; when, changing my lodging, I went over against Pozzo Pinto, where I bought for winter provision 3000 weight of excellent grapes, and pressed my own wine, which proved incomparable liquor.

This was on 10th October. Soon after came to visit me from Venice Mr. Henry Howard, grandchild to the Earl of Arundel, Mr. Bramstone, son to the Lord Chief Justice, and Mr. Henshaw, with whom I went to another part of the city to lodge near St. Catherine’s, over-against the monastery of nuns, where we hired the whole house, and lived very nobly. Here I learned to play on the theorb,66 taught by Signor Dominico Bassano, who had a daughter married to a doctor of laws, that played and sung to nine several instruments, with that skill and address as few masters in Italy exceeded her ; she likewise composed divers excellent pieces. I had never seen any play on the Naples viol before. She presented me afterwards with two recitatives of hers, both words and music.

31st October. Being my birth-day, the nuns of St. Catherine’s sent me flowers of silk-work. We were very studious all this winter till Christmas, when, on Twelfthday, we invited all the English and Scots in town to a feast, which sunk our excellent wine considerably.

1645-6. In January, Signor Molino was chosen Doge of Venice,67 but the extreme snow that fell, and the cold, hindered my going to see the solemnity, so as I stirred not from Padua till Shrovetide, when all the world repair to Venice, to see the folly and madness of the Carnival68 ; the women, men, and persons of all conditions disguising themselves in antique dresses, with extravagant music and a thousand gambols, traversing the streets from house to house, all places being then accessible and free to enter. Abroad, they fling eggs filled with sweet water, but sometimes not over-sweet. They also have a barbarous custom of hunting bulls about the streets and piazzas, which is very dangerous, the passages being generally narrow. The youth of the several wards and parishes contend in other masteries and pastimes, so that it is impossible to recount the universal madness of this place during this time of license. The great banks are set up for those who will play at bassett ; the comedians have liberty, and the operas are open ; witty pasquils are thrown about, and the mountebanks have their stages at every corner. The diversion which chiefly took me up was three noble operas, where were excellent voices and music, the most celebrated of which was the famous Anna Rencha,69 whom we invited to a fish-dinner after four days in Lent, when they had given over at the theatre. Accompanied with an eunuch whom she brought with her, she entertained us with rare music, both of them singing to a harpsichord. It growing late, a gentleman of Venice came for her, to show her the galleys, now ready to sail for Candia. This entertainment produced a second, given us by the English consul of the merchants, inviting us to his house, where he had the Genoese, the most celebrated base in Italy, who was one of the late opera-band. This diversion held us so late at night, that, conveying a gentlewoman who had supped with us to her gondola at the usual place of landing, we were shot at by two carbines from another gondola, in which were a noble Venetian and his courtezan unwilling to be disturbed, which made us run in and fetch other weapons, not knowing what the matter was, till we were informed of the danger we might incur by pursuing it farther.

Three days after this, I took my leave of Venice, and went to Padua, to be present at the famous anatomy lecture, celebrated here with extraordinary apparatus, lasting almost a whole month. During this time, I saw a woman, a child, and a man dissected with all the manual operations of the chirurgeon on the human body. The one was performed by Cavalier Veslingius and Dr. Jo. Athelsteinus Leonænas, of whom I purchased those rare tables of veins and nerves, and caused him to prepare a third of the lungs, liver, and nervi sexti par: with the gastric veins, which I sent into England, and afterwards presented to the Royal Society, being the first of that kind that had been seen there, and, for aught I know, in the world, though afterwards there were others. When the anatomy lectures, which were in the mornings, were ended, I went to see cures done in the hospitals ; and certainly as there are the greatest helps and the most skilful physicians, so there are the most miserable and deplorable objects to exercise upon. Nor is there any, I should think, so powerful an argument against the vice reigning in this licentious country, as to be spectator of the misery these poor creatures undergo. They are indeed very carefully attended, and with extraordinary charity.

20th March. I returned to Venice, where I took leave of my friends.

22nd. I was invited to excellent English potted venison, at Mr. Hobbson’s, a worthy merchant.

23rd. I took my leave of the Patriarch and the Prince of Wirtemberg, and Monsieur Grotius (son of the learned Hugo) now going as commander to Candia ; and, in the afternoon, received of Vandervoort, my merchant, my bills of exchange of 300 ducats for my journey. He showed me his rare collection of Italian books, esteemed very curious, and of good value.

The next day, I was conducted to the Ghetta,70 where the Jews dwell together in as a tribe, or ward, where I was present at a marriage. The bride was clad in white, sitting in a lofty chair, and covered with a white veil ; then two old Rabbis joined them together, one of them holding a glass of wine in his hand, which, in the midst of the ceremony, pretending to deliver to the woman, he let fall, the breaking whereof was to signify the frailty of our nature, and that we must expect disasters and crosses amidst all enjoyments. This done, we had a fine banquet, and were brought into the bride-chamber, where the bed was dressed up with flowers, and the counterpane strewed in works. At this ceremony, we saw divers very beautiful Portuguese Jewesses, with whom we had some conversation.

I went to the Spanish Ambassador with Bonifacio, his confessor, and obtained his pass to serve me in the Spanish dominions; without which I was not to travel, in this pompous form:

” Don Gaspar de Teves y Guzman, Marques de la Fuente, Senor Le Lerena y Verazuza, Comendador de Colos, en la Orden de Sant Yago, Alcalde Mayor perpetuo y Escrivano Mayor de la Ciudad de Sevilla, Gentilhombre de la Camara de S. M. su Azimilero Mayor, de su Consejo, su Embaxador extraordinario a los Principes de Italia, y Alemania, y a esta serenissima Republica de Venetia, &c. Haviendo de partir de esta Ciudad para LaMilan el Signior Cavallero Evelyn Ingles, con un Criado, mi ban pedido Passa-porte para los Estates de su M. Le he mandado dar el presente, firmado de mi mano, y sellado con el sello de mis armas, por el qual encargo a todos los menestros de S. M. antes quien le presentase y a los que no lo son, supplico les dare passar libramente sin permitir que se le haya vexacion alguna antes mandar le las favor para continuar su viage. Fecho en Venecia a 24 del mes de Marzo dell an’o 1646.

Mar. de la Fuentes, &c.”

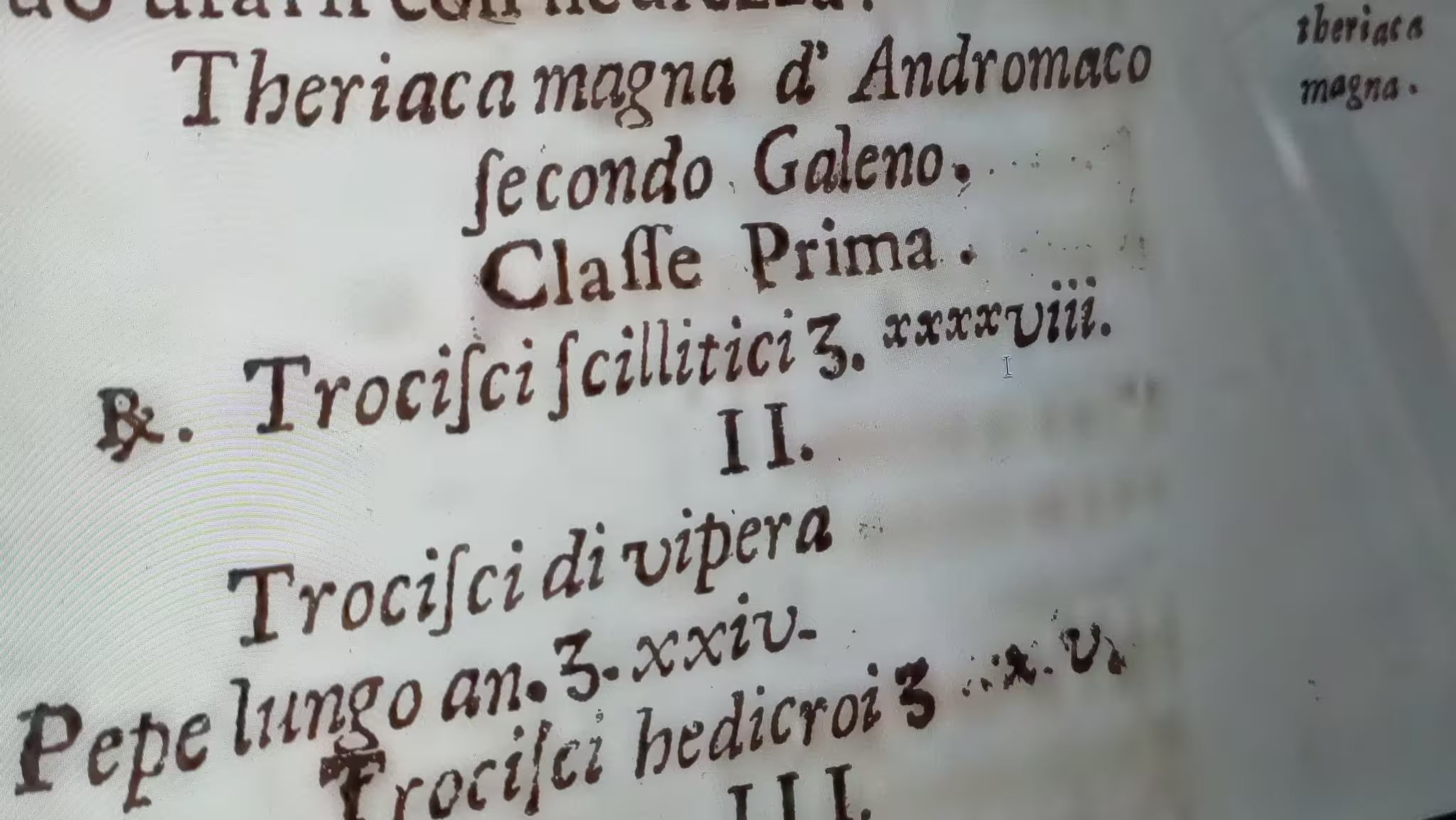

Having packed up my purchases of books, pictures, casts, treacle, &c., (the making and extraordinary ceremony whereof I had been curious to observe, for it is extremely pompous and worth seeing)71 I departed from Venice, accompanied with Mr. Waller (the celebrated poet), now newly gotten out of England, after the Parliament had extremely worried him for attempting to put in execution the commission of Array, and for which the rest of his colleagues were hanged by the rebels.

Notes

- Chioggia at the southern end of the current extent of the Venetian Lagoon. ↩︎

- Pellestrina, on the island of the same name, just south of the Lido di Venezia. ↩︎

- Malamocco, on the southern end of the Lido di Venezia, was where ships entering the lagoon from the south, at Alberoni, would throw anchor waiting for permission to approach Venice — see Malamocco, Matemauco, Metemaucum — Lessico Veneto. ↩︎

- Valid health certificates — fedi di sanità — had to be presented to avoid quarantine in the lazzaretti to prevent the black plague. ↩︎

- The customs house in Dorsoduro, just across from San Marco and the Palazzo Ducale. ↩︎

- The Aquila Nera was a well-known inn during the 1500s and 1600s, located at San Bartolomeo near the Rialto Bridge. ↩︎

- See Invasions of Italy in Late Antiquity. ↩︎

- Candia was the Venetian name for the island of Crete. ↩︎

- Schiavonia was on the Adriatic coast in modern-day Croatia. ↩︎

- This is the ancient Festa della Sensa, which disappeared with the fall of the Republic of Venice, but has since been resuscitated. ↩︎

- The Bucintoro (meaning Golden ship) was a ceremonial galley used by the Doge on official occasions. The last Bucintoro was burned in 1797. ↩︎

- An alternative spelling of the Lido di Venezia. ↩︎

- The gondolas of the 1600s looked different from modern gondolas, and in particular they often had two irons, both front and back, with a varying number of fingers. ↩︎

- Evelyn seems to compare the Rialto markets with the London exchange, which was much more monumental. ↩︎

- The Fontego dei Tedeschi is now a luxury mall, before that post office. It was originally the trading station of the Germans, which meant any merchant from Northern Europe, also English. ↩︎

- In the 1500s and 1600s, many buildings had frescoes painted on the façades, most of which have been lost. ↩︎

- The Merceria is a series of roads connecting the Rialto Bridge with the area of San Marco, which was a traditional area for merchants of cloth, linen, silk and anything related. ↩︎

- For more about songbirds in cages in Venice, see Nightingale Muzak, and the sources Osei, che canta and Il mermeo in giro. ↩︎

- The church of San Giminano, by Sansovino, stood where the entrance to the Museo Correr is today. It was demolished during the second French domination in 1805–1815. ↩︎

- There are three flag posts now and then. ↩︎

- The monastery of the Servi di Santa Maria was in Cannaregio, since demolished. ↩︎

- Evelyn mixed up the Consiglio Maggiore and the Venetian Senate, also called the Pregadi or the Rogiti — see State institutions of the Republic of Venice for more details. ↩︎

- This is the Sala del Scrutinio besides the Sala del Maggior Consiglio. ↩︎

- Given the secrecy around the Council of Ten, which was charged with guarding the security of the state, getting to see the armoury must have been quite a privilege. ↩︎

- The tower they climbed collapsed in 1902, and was rebuilt, but now there’s a lift inside. ↩︎

- In Venetian, these plateau sandals are called calcagnette. ↩︎

- Here, tiffany means a kind of thin, transparent silk fabric, suitable for veils and sleeves. ↩︎

- See Prostitution in Venice and A catalogue of Venetian prostitutes. ↩︎

- Citizen here means non-noble, probably in the sense original citizen — see Citizen of the Republic of Venice. ↩︎

- Taffeta is a crisp, glossy silk fabric, fashionable in the 1600s and 1700s. ↩︎

- Venetian needle lace, as it is still made on the island of Burano. ↩︎

- The distinction between nobility and citizens is reflected in the dress codes for the social classes. ↩︎

- Vair (Ven. vaio) is the fur of Baltic or Siberian squirrels, whose winter coat is clear white with a small dark mark. ↩︎

- The Procuratori di San Marco were mostly, but not entirely, an honorific position, held for life. ↩︎

- The moors were Muslims from North Africa. ↩︎

- Sclavonia is on the coast of modern-day Croatia, then a Venetian dominion. ↩︎

- The market at the Rialto, where most trade happened. ↩︎

- There were half a dozen theatres in Venice in the 1600s, and Venice was one of the places to go for theatre lovers. Numerous place names around the city are related to the presence of theatres. ↩︎

- The play Ercole in Lidia, by Maiolino Bisaccioni and Giovanni Rovetta, was performed during 1645 in the short-lived Teatro Novissimo at Campo SS Giovanni e Paolo. ↩︎

- Anna Renzi was a famous and celebrated soprano, who acted in the theatres of Venice in the 1640s. ↩︎

- With an eunuch, Evelyn probably meant a castrato, a male castrated before puberty to keep the voice high. ↩︎

- The word chetto is difficult to decipher, but give the association with gambling, it is probably a casino in one of the palaces on the Grand Canal in the parish of San Felice. ↩︎

- Candia is the Venetian for Crete, which was then a Venetian dominion. The reference is to the start of the Cretan War (1645–1669) which eventually lost Venice Crete. ↩︎

- Rowed war ships, such as galleys and galeasses, were rowed by a mixture of forced labour, prisoners of war and volunteers (buonavoglia). Most of them were de facto in a state of enslavement — Evelyn doesn’t make much of it because slavery was normal. See also Slaves in Venice. ↩︎

- The Corderie, inside the Arsenal, now occupied by the Biennale. ↩︎

- Saltpetre is one of the ingredients of gunpowder. ↩︎

- Various pre-cursors of the guillotine existed since the Middle Ages — see for example, this manuscript from Naples. ↩︎

- Probably the Palazzo Grimani in Ruga Giuffa, which is now a national museum. ↩︎

- Campo SS Giovanni e Paolo in Castello. ↩︎

- The statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni. ↩︎

- The Chiesa di San Giorgio dei Greci. ↩︎

- Somebody from Candia (Crete). ↩︎

- Pietro Aretino (1492-1556), playwright and satirist. ↩︎

- There are quite a few churches in Venice dedicated to Santa Maria, but Evelyn probably meant Santa Maria Formosa, which had the façade on the campo redone in 1604. ↩︎

- The Chiesa di San Polo in the same sestiere. ↩︎

- The church of the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista. ↩︎

- The church and the Scuola Grande di San Rocco. ↩︎

- Santo Spirito is a now abandoned island a few kilometres south of Venice. The monastery was suppressed under the French domination, and most of the artworks ended in the Basilica della Madonna della Salute. ↩︎

- There is no island with a San Lorenzo, but given the context, Evelyn might have meant the island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni. ↩︎

- The church and monastery of Sant’Elena was an island, until the adjacent lagoon area was reclaimed in the early 1900s, to create the Sant’Elena quarter. Evelyn went there by boat, but we can walk there. ↩︎

- Murano had a podestà which meant it was a separate administration from Venice. The Municipalità di Murano existed until 1923. ↩︎

- The modern-day cemetery island of San Michele was originally two distinct islands — San Michele and San Cristofero — each with a monastery. The monastery of San Cristofero was suppressed during the French domination, and the two islands united to create space for the modern cemetery. ↩︎

- I have found no corroboration of this story. ↩︎

- There were three churches dedicated to St Nicholas in Venice in the 1600s, but none of them were on the route Evelyn describes, and none were particularly associated with the Giustinian family. The only such church on an island is on the Lido, but given Evelyn’s fixation on the Festa della Sensa, he would have known. My suspicion is that he got the name of the saint wrong. ↩︎

- The usual reference, Da Mosto, Andrea. L'Archivio di Stato di Venezia : indice generale, storico, descrittivo ed analitico in Bibliothèque des Annales Institutorum, 5. Roma : Biblioteca d'arte, 1937, doesn’t list Rugini as a Venetian noble family, and neither as original citizens. There are some similar names, like the aristocratic Ruzzini, and the citizens Regini and Rubini. ↩︎

- A musical instrument. ↩︎

- Francesco Molin, doge 1646–1655. ↩︎

- The Carnival was one of the greatest attractions of the city. ↩︎

- Same Anna Renzi as above. ↩︎

- Clearly a misspelling of Ghetto. ↩︎

- Teriaca (also triaca; English: theriac or treacle) was a kind of wonder medicine and general antidote, of which Venice was the main producer in Europe. ↩︎

Leave a Reply