Living in Venice can be as mundane as anywhere else. We do our shopping, dispose of the rubbish and generally go about daily life like everybody else.

Venetian Stories

This post is an issue of our newsletter — Venetian Stories — which goes out every few weeks, to keep in touch and share stories and titbits from and about Venice and its history.

The limited size of the city, its location in the lagoon, and the age of the place put some constraints on our possibilities, though.

The other day I had to get 90 kg of dog food for the three German shepherds of the Lazzaretto Nuovo. They’re the guardians of the island, and we need to keep them merrily barking until into the new year.

The Lazzaretto Nuovo was part of the defences of the Serenissima against the menace of the Black Plague. The lagoon island thus became the world’s first permanent quarantine station for the plague in 1468. It is now a small museum run by volunteers.

Ninety kg of dog food is more than you can reasonably pick up in Venice. The pet shops are all rather small because, well, everything is rather small. I therefore had to head for the periphery. In this case, that means Treporti on the Lido di Jesolo, north of Venice.

That’s a boat ride of an hour back and forth, at least if you abide by the speed limits. It is not boring, though, because Venice is the lagoon, and the lagoon is Venice.

Historically, Venice only exists because of the lagoon, and the lagoon only exists because of Venice.

Over the years, I’ve met many people who perceive Venice as a jewel in the middle of the mud. For them, Venice is this beautiful, absurd place in the middle of absolutely nothing.

That is not true, and it never has been. Venice is in the middle of the lagoon, which is full of Venetian history because the two were never apart.

The lagoon and Venice were always inseparable, conjoined. A large part of the misery of Venice today is the abandonment of the lagoon.

So, the rest of this newsletter will be about what I saw in the lagoon as I went to get 90 kg of dog food for the canine guardians of the Lazzaretto Nuovo.

The Fortress of Sant’Andrea

The Fortress of Sant’Andrea is from the 1500s, the central part from the early 1400s. It formed a pair with an older fortress across the canal. Together, they guarded the entrance to the lagoon from any attacks on the city from the sea.

The cannons of the fortress were at water’s edge. The distance between the two fortresses was about 300m. To hit incoming ships at their waterline to sink them, the guns had to be at water’s edge. Old style cannons cannot shoot downwards because that would cause the cannonball to roll out.

It situations of danger, the Venetians extended a chain between the two fortresses. That is the purpose of the central gate. To keep the chain up across the entire width of the canal, they placed ironclad barges with more guns along the chain. These barges were the gaggiandre, and in peacetime they stayed inside the Arsenale.

Old texts and maps often refer to the fortress as Castel Novo, the new castle or fortress. The other was the Castel Vecio, the old fortress. Together, they were the Do Castei, the Two Fortresses.

The Fortress of Sant’Andrea was the only place where anybody shot in anger in defence of the Republic of Venice in 1797. The republic fell, nonetheless, and Venice ceased to be a state. The fortress should have been a museum just for that reason, but instead it’s falling apart.

You can visit Sant’Andrea if you have a boat, at least unofficially. Formally it is still military, but in reality the Italian army has abandoned the place decades ago. Nothing is done to keep people out, but even less is done to keep any visitors safe.

The MOSE

There’s not a lot to see of the MOSE above the surface of the lagoon, and what there is, isn’t exactly pretty.

The ancient Venetians took great care of the lagoon because they knew they depended on it. They needed the lagoon for food and for defence, but it was also an absolutely integral part of their history and culture.

They didn’t mess with the overall hydrology of the lagoon because they knew better. We don’t, so we did.

In the 1960s, the modern harbour of Venice needed a connection to the sea that didn’t go in front of San Marco. Consequently, they dug a deep canal across the lagoon south of Venice. Basically, they created a highway for the tide to rush into the lagoon at high speed and in high volumes.

As a result, the number of extreme high tides exploded. Before the new canal, high tides over 140cm were a handful a decade. Afterwards, they were a handful each year. This culminated in the disastrous high tide of November 4th, 1966, which is still remembered today simply as the Acqua Granda.

The MOSE is an attempt to remedy the damage caused by messing with the hydrology of the lagoon. Absurdly, this is done by messing some more with the hydrology of the lagoon.

In synthesis, it is a series of submerged gates at each opening between the lagoon and the sea, which can swing up to block a rising tide.

The name is an obvious reference to Moses, who divided the waters of the Red Sea, but formally it’s a backronym of MOdulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico.

It was supposed to be a showcase of Italian engineering, but instead it became a text book example of Italian corruption.

On the positive side, the system actually works. When the gates are engaged, they do keep the tide substantially lower in the city. On the negative side, the corruption means it is still a building site, it is not officially finished, and it might never be. Who will be responsible for operation, maintenance and who will cover the associated costs, is entirely up in the air.

Then there’s the environmental impact.

While Venice and the lagoon were always one entity, we have taken to contra pose the two, and with the MOSE project we’re potentially sacrificing the lagoon to save Venice.

I’ve written more about the tides of Venice and on my old personal blog.

Treporti

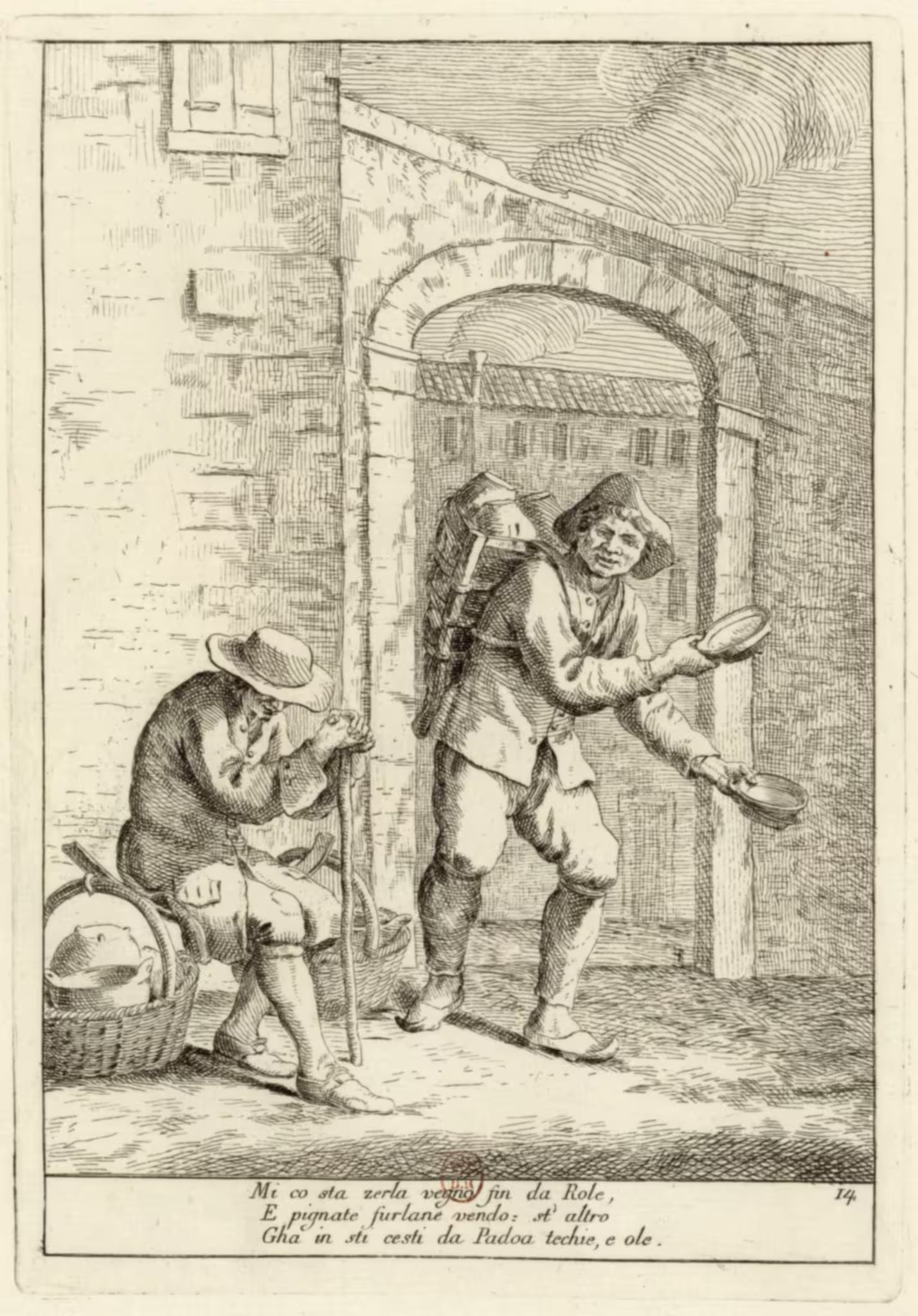

Treporti is one of the many small towns and villages which dotted the Venetian lagoon in the Middle Ages.

The name means Three Harbours. Back then this was where the lagoon canals for the lagoon towns of Torcello (now mostly abandoned), Ammiana (abandoned) and Lio Maggiore (mostly abandoned) divided.

The current village church is mostly modern, but the old church tower from the 1600s is still standing.

This part of the lagoon has changed profoundly, starting with the construction of the piers at the entrance to the lagoon. They changed the coastline both in the lagoon and outside, and later additional modifications came with the construction of the MOSE.

Treporti was once insular. It is now on the Lido di Jesolo, which is a peninsula. The modern appearance of the village is therefore like many others in Italy, with cars and fast traffic.

Torcello

Torcello was once the most important settlement in the Venetian lagoon. Its origins go back to the late 500s or early 600s, when people from the Roman town of Altinus on the mainland sought shelter and protection from the Ostrogoths and Lombards in the lagoon.

In 638, the town was so important that the Byzantine Exarch of Ravenna granted the city’s request to make it an archbishopric. The basilica of Torcello is therefore the oldest church in the lagoon.

Torcello was there before the Venice we know today. In the 600s, Venice was just some scattered settlements in the marshes around the marketplace at Rialto. The Doge, and hence the government of the Venetian state, only moved there after the war with the Franks in 809.

Medieval documents claim that Torcello had a population of some 50,000 persons around the year 1000, which is no doubt very inflated. It would have made it one of the largest European cities at the time. There is no doubt, however, that Torcello was an important commercial and religious centre in the Middle Ages.

Torcello slowly depopulated between the 1200s and the 1400s. Most people moved down towards Venice, which thereby grew in importance. Today there are just a handful of residents around two ancient churches and a museum.

Sant’Erasmo

The island of Sant’Erasmo is now inside the lagoon, but it was once a lido. In fact, there’s still a popular beach on the island.

Eight kilometres long and 1-1½ km wide, it is the closest there is to a Venetian countryside. Today there are around five hundred residents. At the centre of the island, on the lagoon side, is the main village, surprisingly named Sant’Erasmo.

It has, like so many small Italian villages, a church, a city hall and a monument to the fallen of the great wars. In fact, Sant’Erasmo was a municipality, just like Burano and Murano. They joined (or, rather, were made to join) the municipality of Venice in the early 1900s.

The island is still mostly agricultural. Curiously, there are cars on the island, but no ferry service. This means that you can find houses for sale with the car included. If the car is old, it could easily cost more to get the car off the island that to just leave it.

Sant’Erasmo is a great place for a walk or a bicycle ride.

Lazzaretto Nuovo

This good boy, and his two companions, were the reason for my little journey through the Venetian countryside.Most popular articles

They’re the guardians of the Lazzaretto Nuovo, so we don’t lose that bit of cultural heritage once more.

I’m not going to tell you the entire millennial story of the Lazzaretto Nuovo, as this has become too long already. There lots about the Venetian lazzaretti on my History Walks site.

Leave a Reply