Everybody knows the image of the plague doctor, with the beaked mask, the hood and the flowing, black cloak.

Supposedly, in the Venetian lazzaretti, this raven-like figure of death would circulate and swoop down on anybody with just the slightest symptoms of the plague.

It wasn’t so, however.

The instruction manual

The Magistrato alla Sanità set out all the duties of the priore of the lazzaretti — the managers — in a forty-page instruction booklet. The priori received a copy when appointed, for which they had to sign in front of the notary of the magistracy.

The importance of this document is evident from the repeated reprints. There are editions from at least 1656, 1674, 1719 and 1743.

In it, there is only one short mention of the doctor:

Quando alcun morirà nelli Lazaretti, li Priori ne diano immediate parte all’Officio, non permettendo, che li Corpi siano sotterrati, ne tocchi da alcuna persona, se prima non saranno stati veduti dal Medico del Magistrato …

Magistrato alla Sanità (1674), p. 22 — see full text here.

In my translation:

When somebody dies in the lazzaretti, the priors shall immediately give notice to the Office, and not permit that the bodies are buried, or touched by anybody whatsoever, if they haven’t been seen first by the Doctor of the Magistracy …

That’s it.

There were several different groups of people present in the lazzaretti. The priore was the manager responsible in relation to the magistracy. The guardiani — guardians — were responsible for enforcing the minutiae of the rules. The bastazi were workers charged with the cleansing and movement of goods. Finally, there were the people in quarantine, and some outsiders, such as the vivandieri who sold foodstuffs to people in quarantine.

All these groups are mentioned in the document, and for some there are several pages dedicated to what the priore must and must not do in relation to that group.

The doctor of the Magistracy clearly did not have a daily routine in the lazzaretti.

The origin of the masked plague doctor

If the image of the plague doctor with the beak-like mask is ubiquitous — even in Venice today — where did it come from?

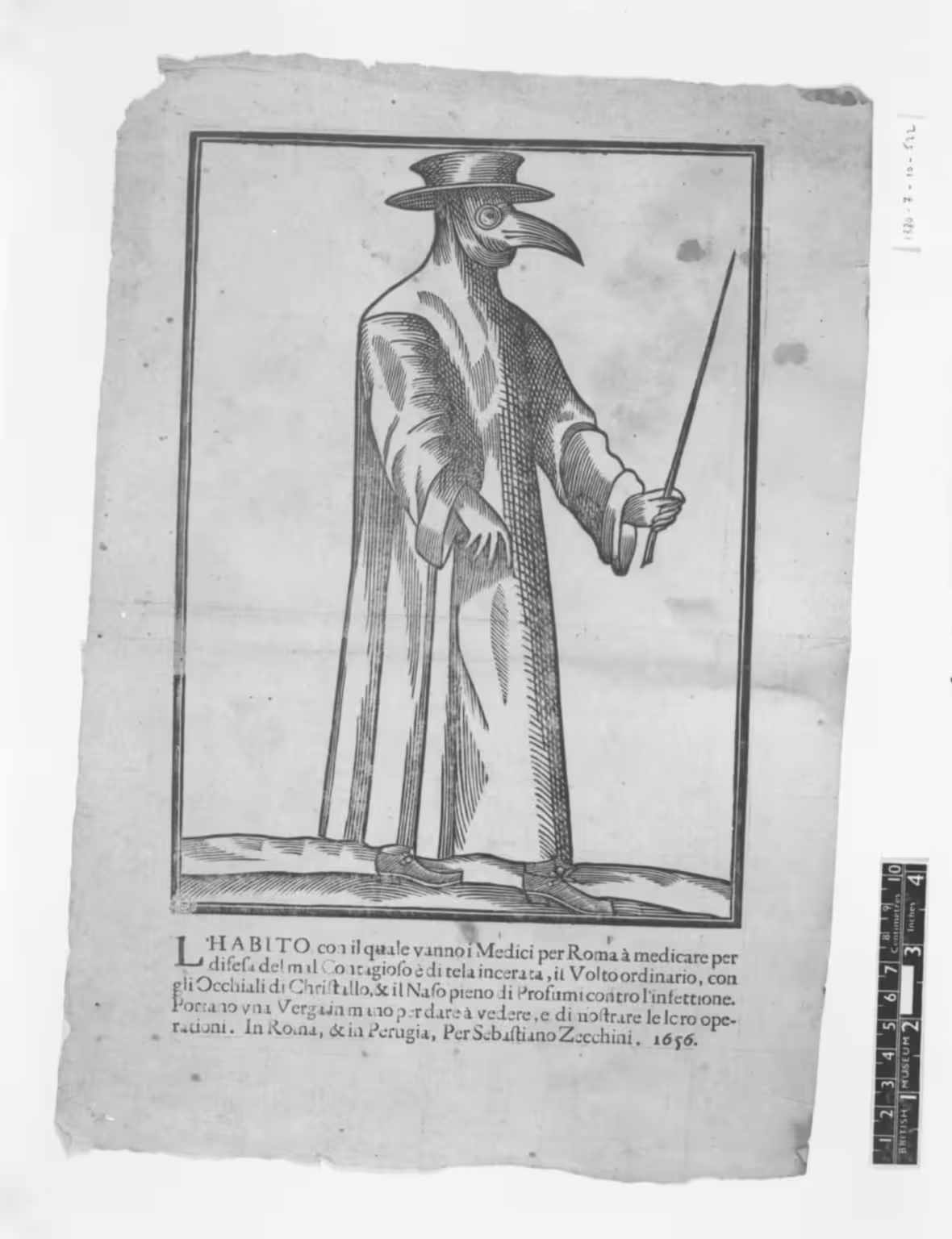

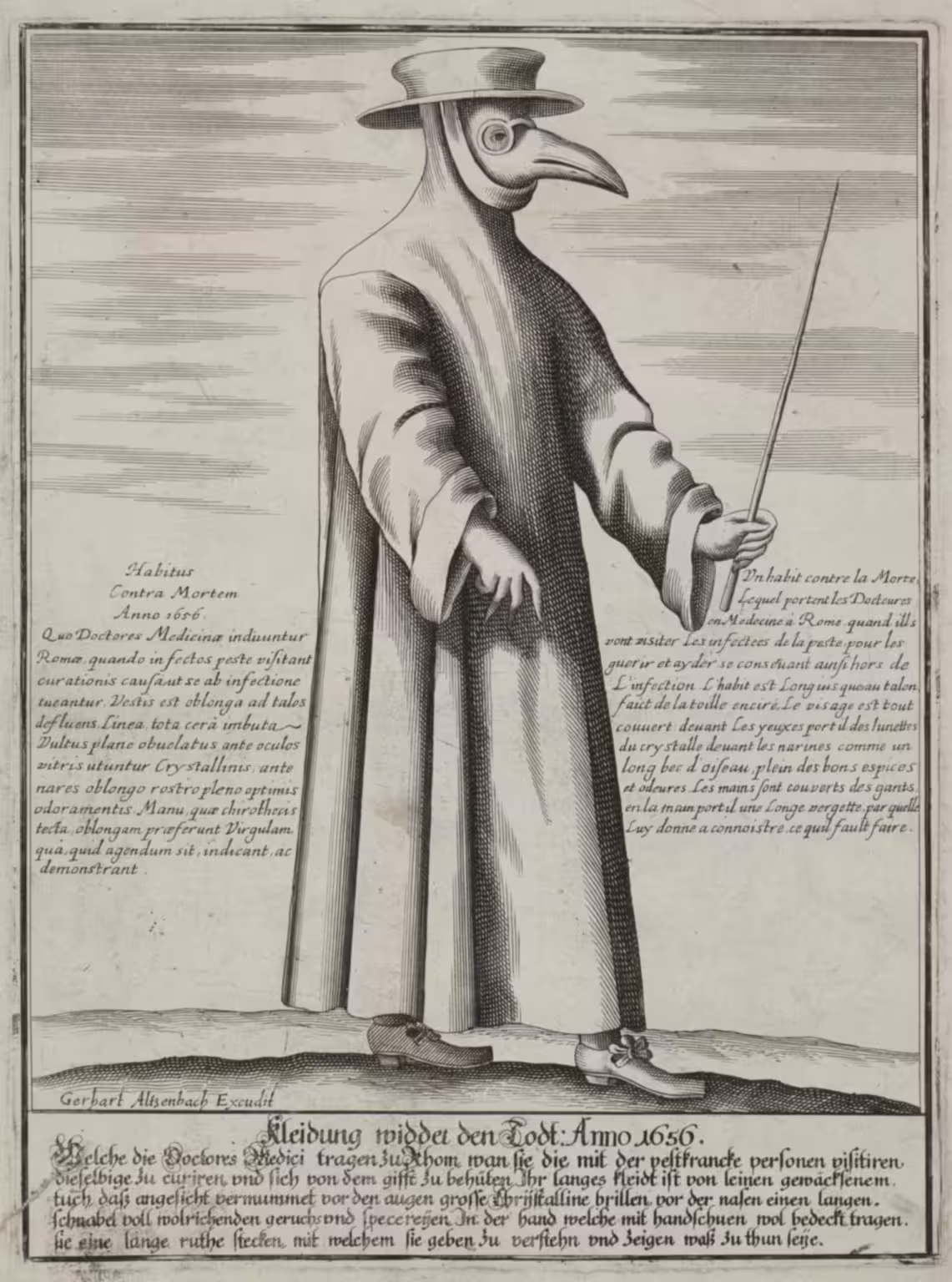

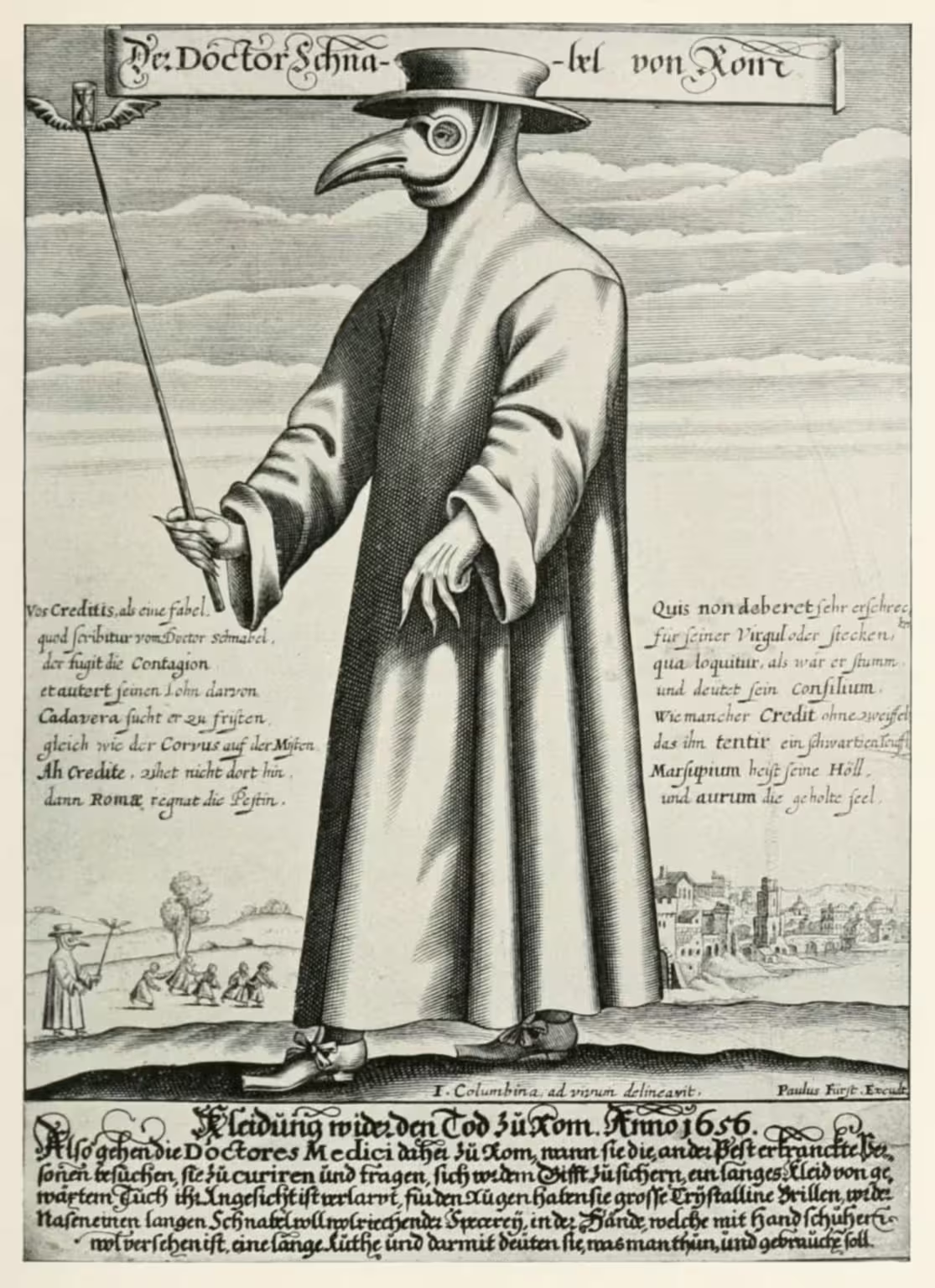

The earliest confirmed images of the plague doctor figure are these:1

All three images are dated to 1656, when a severe epidemic of the black plague hit both Rome and Naples, but spared Venice.

The first illustration is from Rome, by an unknown artist, while the two others are German.

The text on the Roman figures is this:

L’habito con il quale vanno i Medici per Roma a Medicare per difesa del mal Contagioso è di tela incerata, il Volto ordinario, con gli Occhiali di Christallo, & il Naso pieno di Profumi contro l’infettione. Portano una Verga in mano per dare a vedere, e dimostrare le loro operationi. In Roma, & in Perugia, Per Sebastiano Zecchini, 1656.

which is my translation:

The outfit with which the doctors go about Rome to medicate in defence against the bad contagion, is of waxed fabric, the ordinary face, with eyeglasses of crystal, & the nose full of perfumes against the infection. They carry a stick in hand to point, and to demonstrate their operations. In Rome, & in Perugia, For Sebastiano Zecchini, 1656.

The second pamphlet — by Gerhard Altzenbach and also from 1656 — is clearly a copy of the Roman flyer. The text — translated into German, Latin and French — is mostly the same, except for the added title: “An outfit against Death.”

The third flyer — by Paulus Fürst — is very satirical and paints a largely negative image of the plague doctors as greedy and exploitative harbingers of death. The title — Dr. Beaky from Rome — sets the tone. The figure is more sinister, with pointed fingers and a winged hourglass at the end of the stick.

The winged hourglass is a memento mori showing that time flies and death is near. In fact, in the background, the figure of the plague doctor uses this memento mori to scare a group of youngsters. The text on the sides of the figure — in mixed Latin and German — depicts the doctors as half-studied, greedy frauds who are just after whatever money the sick might have.

These three pamphlets — and the latter more than the others — are the basis for our popular image of the masked, hooded and cloaked plague doctor.

Written sources

If we suppose the unknown artist behind the first image from Rome in 1656 didn’t just make it up, where would that kind of outfit originate?

While we have numerous accounts and treatises on the plague from the 1600s and later, very few ever speak of the mask. There are, however, some clues to how the plague doctor appeared.

The goatskin suit of Charles de Lorme — France, 1619

The invention of the protective gear of the plague doctor is generally attributed to Charles De Lorme (1584–1678), who was physician to the King of France in the early 1600s.

However, the description of the outfit comes to us from a much later source. Michel de Saint-Martin wrote a rather hagiographic biography of Charles De Lorme in 1682, which contains a description of a protective suit of Charles De Lorme’s invention:

Il n’oublioit Jamais son habit de marroquin dont il étoit l’autheur, il l’habilloit depuis les pieds jusques à la teste en forme de pantalon, avec un masque du même marroquin où il avoit fait attacher un nez long de demy pied, afin de detourner la malignité de l’air, on en voir encore le modèle chez Mademoiselle Regnaud fille unique de seu Monsieur Regnaud, premier Chirurgien du Grand Louis le Juste.

Saint Martin (1683), pp. 424–425.

In translation:

He never forgot his goatskin outfit of which he was the inventor, he dressed it from the feet to the head in the form of trousers, with a mask of the same goatskin to which he had attached a half-foot long nose, in order to divert the malignity of the air, we still see the model at Mademoiselle Regnaud, only daughter of the late Monsieur Regnaud, first surgeon to the great Louis the XIII.

A subsequent reprint of the first edition of the book had an addendum, where we find this quote:

On doit faire cas de l’invention de Monsieur de Lorme, qui pour être utile à la capitale du Royaume, & la garantia d’un des fleaux de Dieu, se fit faire un habit de marroquin, que le mauvais air penetre tres difficilement, il mist en sa bouche de l’ail & de la rue, il se mist de l’encens dans le nez & les oreilles, couvrit ses yeux de besicles, & en cet équipage assista les malades, & il en guerit presqu’autant qu’il donna de remedes. L’invention dont il se servit huit ans aprés, au siege de la Rochelle, …

ibid., pp. 21–22 of the addendum.

In my poor translation:

We must take note of the invention of Monsieur de Lorme, who, to be useful to the capital of the Kingdom, and safeguard it from one of the scourges of God, had a goatskin garment made for himself, which the bad air penetrates with great difficulty, he put garlic and rue in his mouth, he put incense in his nose and ears, covered his eyes with spectacles, and in this outfit assisted the sick, and he cured almost as many as he gave remedies. The invention served him eight years later, at the siege of La Rochelle, …

Rue — or herb-of-grace — was one of the many plants used in medicines in the past. The siege of Rochelle was in 1627-28, so Charles de Lorme probably invented the protective suit around the time of the plague epidemic in Paris in 1619.

In any case, we have the basics here: a long cloak of a smooth material, with a beaked mask with glass goggles.

Francesco Pona — Verona, 1631

The last devastating plague epidemic hit Venice and its dominions in 1630–1631. It also ravaged the city of Verona.

Francesco Pona — doctor, philosopher and writer from — wrote a description of the event.

Related to the plague doctor, he wrote:

La Città di Lucca, secondando l’uso de’ Medici della Francia, in questa stessa mala influenza, stabili, che gli Medici deputati, si vestissero à lungo, di sottil drappo incerato, e che incaperrucciati del medesimo, con cristalli avanti gli occhi, si avvicinassero à gl’infetti. Così è meno patente la vìa all’offesa ; perche l’halito maligno, non ha sì facile lo spiraglio, onde possa insinuarsi ad esser attratto, con la respiratione. Suppongo, presso tale avvedimento, l’uso anco de gli aceti medicati ; dell’herbe odorìfere, de gli antìdoti proportionati.

Pona (1631), p. 30.

Translated:

The City of Lucca, following the custom of the French Doctors, in this same evil influence, established that the appointed Doctors should dress in a long cloak, of thin waxed cloth, and that, hooded in the same, with crystals before their eyes, they approached the infected. Thus, the path to contagion is less obvious; because the malignant breath does not have such an easy opening through which it can creep in and be attracted through breathing. I suppose, following this advice, the use of medicinal vinegars; of odoriferous herbs, of proportioned antidotes.

There are several things worth noting here.

Firstly, while the text is about Verona, this section is about the Florentine city of Lucca. Pona compares the different approaches in the two cities. We can therefore assume that Verona did not enforce such provisions on the appointed plague doctors during the epidemic of 1631–31. Otherwise, there would be no reason to pull Lucca into the discussion.

Secondly, he clearly and explicitly states that it is a French idea.

Thirdly and lastly, while he speaks of a hood of waxed cloth with goggles in front of the eyes, there is no mention of a mask, or any beak-like protrusion for that matter.

Francesco Rondinelli — Florence, 1634

A similar text to the above, but for the epidemics in Florence in 1631 and in 1634 — by Francesco Rondinelli (1589-1665) — contains almost nothing about the protective clothing of front-line workers:

Ogni quartiere aveva il suo Fisico, Cerusico, e Speziale , vestivano d’incerato, abitavano separati …

Rondinelli (1634), p. 49.

Translated:

Each quarter had its own Physician, Surgeon, and Pharmacist, they dressed in waxed fabric, lived separately, …

No masks, no beaks, no glass goggles.

If something as conspicuous as a beaked mask with glass goggles is left out of the description, but waxed fabric is not, the mask probably wasn’t there.

Fabritio Ardizzone — Genoa, 1656

Fabritio Ardizzone was a doctor in Genoa in the 1600s, and he published his experiences related to the plague. In Ricordi di Fabritio Ardizzone fisico intorno al preservarsi, e curarsi della Peste, from 1656, he wrote about touching suspect objects:

non doveremmo però dire che toccata alla sfuggita, communichi il contagio così facilmente; oltre che può anco rimediarsi con tener sempre sopra i vestimenti una cappa di coio bagnata d’aceto, ò vero di taffettà, ò tela incerata.

Ardizzone (1656), p. 36.

My translation:

However, we shouldn’t say that touching lightly communicates the contagion so easily; furthermore a remedy is to wear always over the clothes a cape of leather soaked in vinegar, or of taffeta,2 or waxed canvas.

Ardizzone also recommended that doctors washed their hands in vinegar after having touched an infected person.

In any case, it doesn’t sound like Ardizzone used beaked masks with crystal goggles when he attended to plague patients.

The advice of Lodovico Muratori

Lodovico Antonio Muratori (1672–1750) was the court librarian of the Duke of Modena in the early 1700s. He was a prolific writer, and published in 1710 his Del governo della peste, e delle maniere de guardarsene — On the management of the plague and how to protect oneself. Like many other treatises of the plague, it was reprinted repeatedly in different nations over the following decades.

On how to dress in the presence of the sick or suspect, Muratori wrote:

Sarebbe bene allora per tutti quei, che escono di Casa, ma certo farà spezialmente bene, anzi necessario per chi dee praticar gente Ammorbata, il portare una sopraveste di Tela incerata, o pure di Marocchino, o d’altro cuoio sottile (queste si credono migliori di tutte) ovvero di Taffetà, o d’altra manifattura di Seta, perché alle vesti di Lana troppo facilmente s’attaccano gli spiriti velenosi del Morbo, ma non già s’attaccano se non difficilmente (per quanto vien creduto) alle Incerate, e a’ Marocchini, e non si possono ritener lungo tempo dalla Seta spiegata. Avvertasi però, che le vesti di Seta non debbono essere fatte con lusso, né con gran cannoni, e piegature, ma hanno da farsi povere, e più tosto corte; avendo lasciato scritto il Mercuriale, che alcuni Medici nella Peste di Venezia de’ suoi dì si tirarono addosso la rovina per aver nelle visite degl’Infetti portate vesti lunghe e larghe, e belle pelliccie, secondo l’uso d’allora. Chi non ha Seta, né altro di meglio, usi almen Lino, o Canape, più tosto che Lana. Alcuni hanno talvolta usato di coprir’ anche la faccia con una maschera, o bautta, a cui mettevano due occhi di cristallo; ma non é necessaria tanta scrupolosità.

Muratori (1714), pp. 73–74.

In my translation:

It would be good then for all those who leave home, but it will certainly be especially good, indeed necessary for those who have to work with diseased people, to wear an overcoat of waxed cloth, or even goatskin leather, or of other thin leather (these are believed to be best of all} or of Taffeta, or of other Silk fabric because the poisonous spirits of the Disease attach themselves too easily to Woolen garments, but they do not attach themselves except with difficulty (as far as is believed) to the Waxed ones, and to goatskin, and they cannot remain for a long time on unfolded silk. However, note that the silk garments must not be made with luxury, nor with large sleeves and folds, but must be made poor, and rather short; Mercurial having left written that some Venetian Plague Doctors in their days brought upon themselves ruin by having worn long, loose robes and beautiful furs when visiting the Infected, according to the custom of the time. Who doesn’t have Silk, nor anything better, should use at least linen or hemp, rather than wool. Some have sometimes also used to cover the face with a mask, or bautta, on which they placed two crystal eyeglasses; but such scrupulousness is not necessary.

The bautta (or bauta) was a traditional Venetian mask, much used by both men and women of the aristocracy for privacy reasons, also outside the carnival season. It has a very short beak-like protuberance to allow the wearer to drink and eat, but nothing like the long beak of the plague mask.

Hence, Muratori knew that some people covered their face with a mask, but he thought it was unnecessary. On the other hand, he agreed on the use of garments of smooth material like thin leather, silk or waxed fabrics.

Jean-Jacques Manget after the Marseilles plague

Jean-Jacques Manget (1652–1742), from Geneva, published a compilation of the medical knowledge after the epidemic in Marseilles in 1721. In the Traité de la peste he included a drawing of the plague doctor, just before the title page.

The text below the figure is, in my translation:

The outfit of the Doctors and other persons tending to the plague infected. It is of Levantine goatskin, the mask has eyes of crystal, and a long nose full of perfumes.

At the end of the first part of the treatise, Manget explained the figure:

L’Habit exprimé dans cette figure n’est pas une chose de nouvelle invention, & dont on ait commencé l’usage dans La derniére Peste de Marseille : Il est d’une plus vieille datte, & Messieurs les Italiens ont fourni à peu près de semblables figures; depuis fort longues années. Le nés en forme de bec, rempli de Purfums, & oint intérieurement de matiéres balsamiques, n’a véritablesment que deux trous; une de chaque côté, à l’endroit des ouvertures du nés naturel; mais cela peut suffire pour la respiration, & pour porter avec l’air que l’on respire l’inpression dés drogues renfermées plus avant dans le bec. Sous le Manteau, on porte ordinairement des Bottines à peu près à la Polonoise; faites de Maroquin de Levant; des Culottes de Peau unie, qui s’attachent aux dites Bottines; & une Chemisette aussi de Peau unie, dont on renferme le Bas dans les Culottes, le Chapeau & les Gans sont aussi de même Peau.

Manget (1721), p. 320.

Translated:

The outfit shown in this figure is not a thing of new invention, and the use of which began in The Last Plague of Marseilles: It is of an older date, and the Italians have provided almost similar figures; for many years. The beak-shaped nose, filled with Perfumes, and anointed internally with balsamic materials, only has two holes; one on each side, at the place of the openings of the natural nose; but this can be enough for breathing, and to carry with the air one breathes the impression of the drugs contained further in the beak. Under the coat, one usually wears ankle boots more or less in the Polish style; made of Levantine goatskin; plain skin breeches, which attach to the said ankle boots; & a shirt also of plain skin, the bottom of which is enclosed in the breeches, the hat and the gloves are also of the same skin.

With Manget we’ve come full circle from Charles de Lorme a century earlier, and the Roman and German flyers from 1656. Interestingly, he states that the figure and the protective gear are Italian, while the Italian writers say they are French.

Where’s Venice?

None of the flyers or treatises make any connection whatsoever to Venice.

The only source from Venetian governed territory — Francesco Pona from Verona — mentioned elements of the protective suit, but clearly stated that it was not used in Verona.

Muratori — from Modena, which was another country even if not too distant from Venice — associated the beaked mask with the Venetian bauta (or more correctly, the larva), but thought it unnecessary and useless.

There is nothing, in the sources I have found, which links the figure of the plague doctor with the beaked mask to Venice.

There are links to Rome, and more often, to France.

Yet in modern pop culture, the mask with the long beak is associated with Venice.

The only reason I can think of, is the prominence of the Venetian carnival, both in the 1700s and in more recent times. The carnival has created a bond between Venice and carnival masks, and the plague doctor’s mask has become a part of that.

Other myths

There can be little doubt that medieval doctors did what they could — and thought useful — to protect themselves. People were terrified of the plague, and with good reason.

We have no reasons, however, to believe they used anything akin to the raven-like mask. The popular figure of the plague doctor, and the mask, are at best from the early 1600s, and more probably from the mid-1600s.

Even in the 1600s and later, the lack of references to the mask in our sources is conspicuous. If that mask was in common use, why are the writers on the plague — many of whom were doctors and physicians themselves — so silent or plainly dismissive on the matter.

One possible explanation could be that the mask was never really used by the doctors, if not much later.

Rather, it was used during the carnival and in theatrical settings to ridicule the plague doctors. This would be well in line with the satirical flyer by Paulus Fürst from 1656.

An intriguing painting of the Carnival in Rome — by Johannes Lingelbach from around 1650 — might show one or two participants in the carnival procession dressed in bird-like costumes. In that case, that painting is the earliest image we have of a plague doctor mask. It is not, however, worn by a doctor, but by carnival procession participants — actors.

Another possible explanation could be, that the beaked mask was used by a few, very high-profile doctors in Rome or in France, and that the attention they gathered created the popular image of the figure of the plague doctor, even if the vast majority of doctors didn’t use anything like it.

Just consider what the Indiana Jones franchise has done to distort the public image of archaeologists.

Update — Grevembroch drawing

Herbert J. Mattie in a comment below pointed me to a watercolour by Giovanni Grevembroch, from the mid-1700s, which influenced the public image of the plague doctor in Venice in the late 1700s.

I have acquired the volumes with the drawing, and translated the relevant page.

Grevembroch’s drawing is clearly inspired, directly or indirectly, by the original pamphlets from 1656, as the figure and posture is very close to both the Roman and the Altzenbach images.

That the beaked and masked figure wasn’t a common sight in Venice in the mid-1700s is clear from Grevembroch’s dedication: “We also show this curious entertainment to Mr. Domenico Vincenti, trader in medicinal herbs in S. Maria Mater Domini, and lover of all rare knowledge.”

Notes

- The Roman engraving is in the British Library (BM 1880,0710.522); the Altzenbach flyer is in the Yale Medical Historical Library (OID 17338851); and the Fürst flyer is in the British Library (BM 1876,0510.512). ↩︎

- Taffeta is a crisp, glossy silk fabric, fashionable in the 1600s and 1700s. ↩︎

Related articles

- Bad air will get you sick

- The Black Plague

- A Chronology of the Black Plague in Venice

- The Venetian Lazzaretti

- Capitoli Da osservarsi nelli Lazaretti — 1674

- 404 Doctor Not Found — Venetian Stories newsletter

- Glossary — clothing

Bibliography

- Ardizzone, Fabrizio. Ricordi di Fabritio Ardizzone fisico intorno al preseruarsi, e curarsi dalla peste. In Genova per Gio. Maria Farroni, 1656. 🔗

- Manget, Jean-Jacques. Traité de la peste. A Geneve Chez Philippe Planche, 1721. 🔗

- Muratori, Lodovico Antonio. Del governo della peste, e delle maniere di guardarsene, trattato di Lodovico Antonio Muratori … diviso in politico, medico, et ecclesiastico. In Modena : per Bartolomeo Soliani, 1714.

- Pona, Francesco. Il gran contagio di Verona nel milleseicento, e trenta. Descritto da Francesco Pona. In Verona per Bartolomio Merlo. Stampator camerale, 1631. [more] 🔗

- Rondinelli, Francesco. Relazione del contagio stato in Firenze l'anno 1630. e 1633. In Fiorenza per Gio. Batista Landini, 1634.

- Saint Martin, Michel de. Moyens faciles et eprouvez Dont Monsieur de Lorme, Premier Medecin & Ordinaire de trois de nos Roys , & Ambaffadeur à Cleves pour le Duc de Nevers, s'est servy pour vivre cent ans.. Caen / Paris, 1683.

Links

Did plague doctors wear those masks? — by Kathleen Crowther.

Mask of the Plague Doctor and three follow-up posts— by Jonathan Ferguson.

Behind the Beak: Plague Doctor Iconography in 2020 — by Madeleine Mant.

Leave a Reply