Who would expect to find runes in Venice? After all, the Vikings never did come to Venice, even if they did go a little bit everywhere.

In fact, the closest the Vikings ever got to Venice was southern Italy and the lower Adriatic.

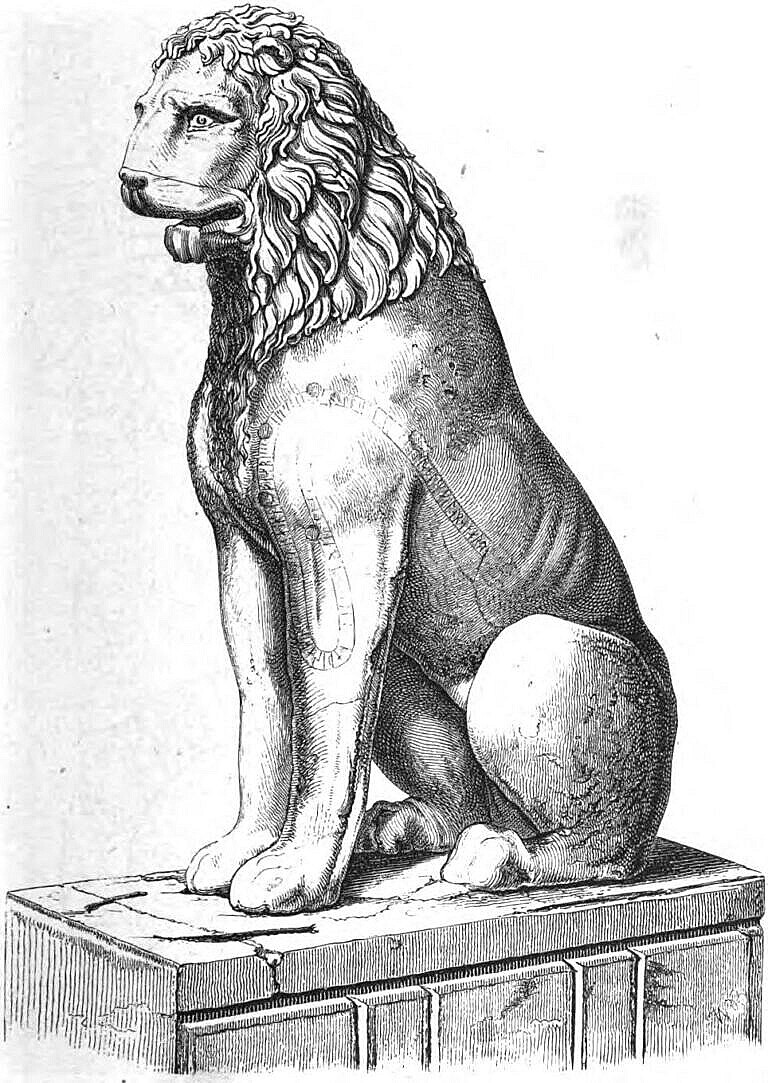

Yet, in central Venice, at the entrance to the Arsenale — the ancient Venetian navy docks — there is a statue of a lion with several runic inscriptions on both shoulders and one of the legs.

The story is two thousand years long, and it starts in Ancient Greece.

The Piraeus Lion

The lion is one of a pair, both of them in Venice in the Campo de l’Arsenal.

The statues are of Greek origin, dating to the 300s or 400s BC. Where they were originally is not known, but in the first century AD they appeared in Piraeus.

The sitting lion, the one with the runes, stood at the harbour of Piraeus close to Athens in Greece. The lying lioness statue stood along the way from the harbour in Piraeus to the city of Athens.

For at least some of the time the sitting lion, with the runic inscription, must have served as a fountain. There’s a hole in its mouth, and there are signs of a tube having run down its back.

For over a millennium and a half, they remained in Piraeus.

The presence of the sitting lion was so majestic and dominant that the sailors of the Mediterranean referred to Piraeus simply as Porto Leone — Lion Harbour.

Why is the statue in Venice?

In 1683, the Ottoman Turks tried to take Vienna in a month-long siege. Christian Western Europe saw this as an existential fight, so it was deeply felt in much of Europe. In Venice, it led, indirectly, to a major fire caused by religious processions in the city.

When the Ottoman siege of Vienna failed, the Western countries went on the offensive. Venice tried to use this period of Ottoman weakness to take control of many Greek islands in a campaign which lasted several years.

The Capitan da Mar — Captain of the Sea, which meant top admiral of the Venetian navy — was Francesco Morosini. He is considered one of the greatest Venetian admirals of all time.

Between 1683 and 1687 he took city after city, island after island, in Southern Greece, until he had taken almost all of Morea — the Venetian name for the Peloponnese. Later, on his return to Venice, the Senate gave him the honorary title of Peloponnesiaco for this achievement.

In 1687, he wanted to continue to take Eubea — Negroponte to the Venetians — which is a major island close to Athens. The Senate, however, ordered him to take Athens instead.

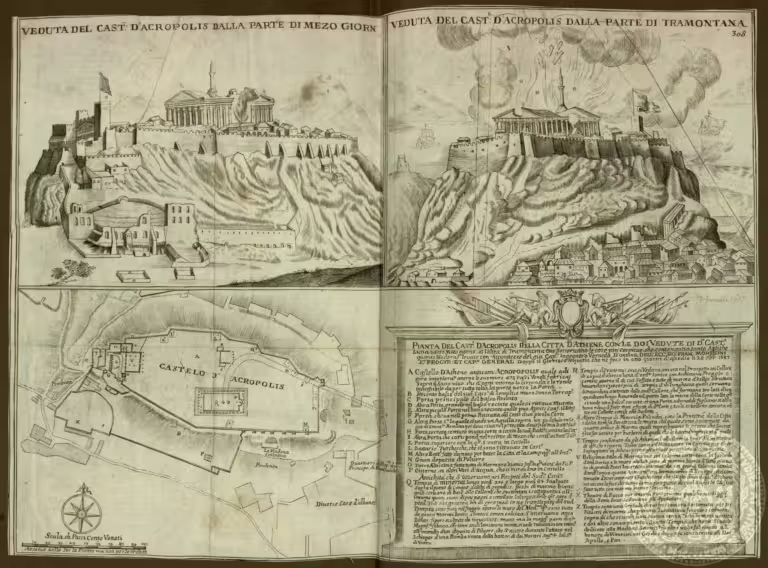

Athens was a hilltop town, inland from Piraeus, with a citadel on the Acropolis rock where the Parthenon stands.

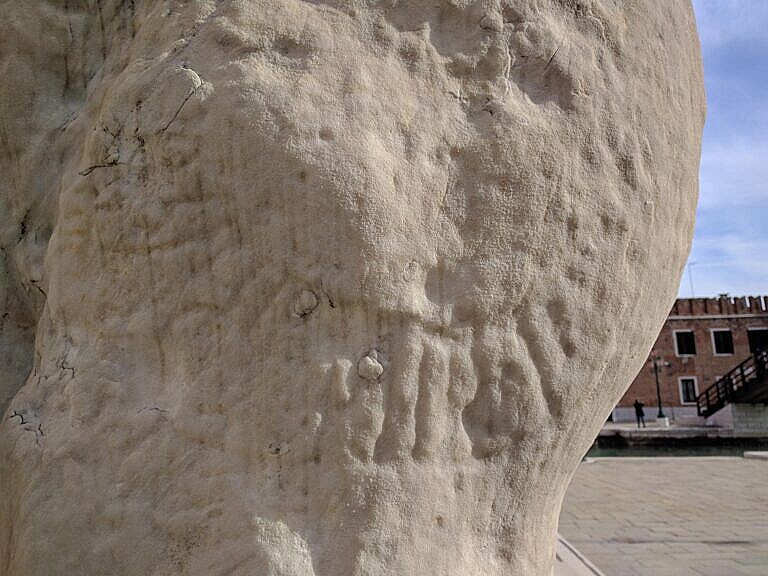

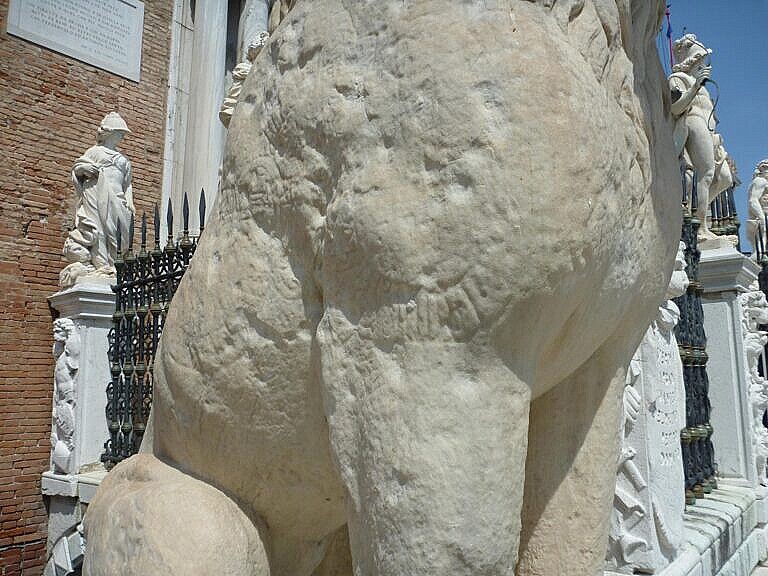

On September 21st, 1687, the Venetian navy entered the harbour of Piraeus, guns ablaze. The many pockmark-like round holes on the lion are testimony to this bombardment of the harbour.

The troops of Morosini quickly took control of the city of Athens, but the Ottoman garrison and parts of the population sought refuge on the Acropolis. In a siege of the Acropolis from the 23rd to the 29th, the citadel was bombarded relentlessly.

On the evening of September 26th, the Venetian guns hit the Parthenon itself, which the Ottoman Turks had used for storing their gunpowder. The massive explosion killed some 200–300 persons, and almost entirely destroyed the ancient temple, whose wooden roof had miraculously survived two millennia.

In the end, the Turkish garrison surrendered in return for free passage, and Morosini could add another victory to his very long list. However, without control of the rest of Attica, the situation wasn’t tenable for the Venetians, and in April 1688, they withdrew to the Peloponnese.

As the Venetian forces left Athens, they took the two lion statues with them as trophies of war — because of St Mark. The Venetians rarely missed an opportunity to loot a lion.

On top of the damage from the shelling of the harbour of Piraeus in 1687, the ropes used to move the two statues first onto the Venetian ships, and then into the Arsenale in Venice, have damaged the surface of the lions, and hence also the runic inscriptions, even further.

The discovery of the runes

The lions ended up in the Campo de l’Arsenal shortly after arriving in Venice, and they have been there ever since.

The runes weren’t recognised as such until the Swedish diplomat Johan David Åkerblad in the late 1790s realised that the signs were runes. He had drawings made, which were sent back to Stockholm.

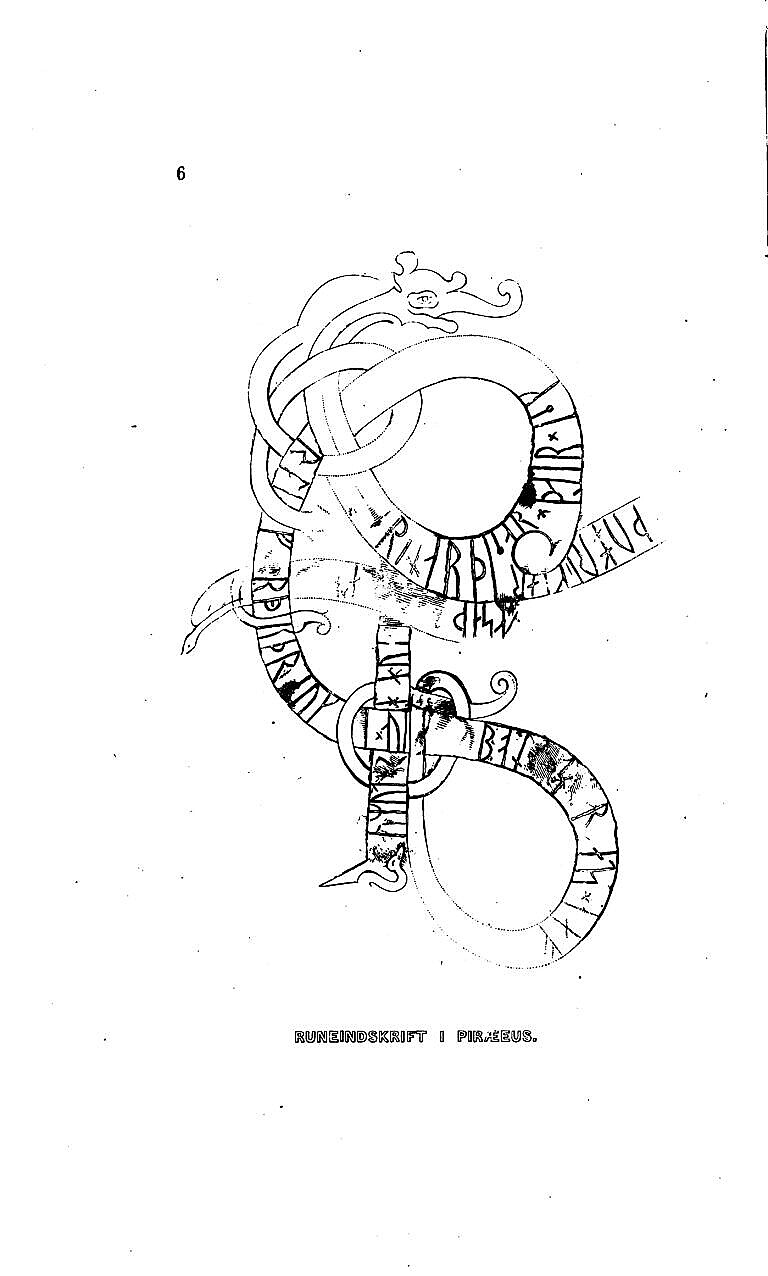

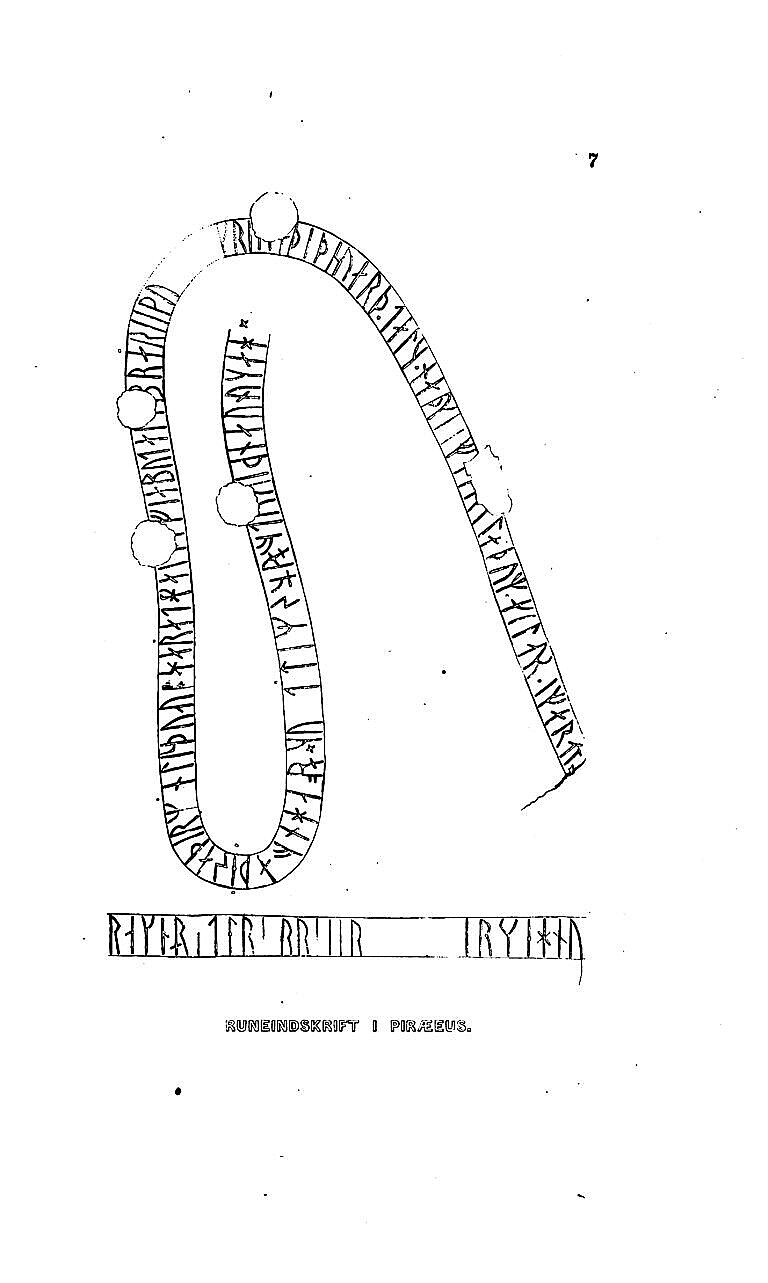

The writings are made on twirling bands, which is not unusual for runic inscriptions. On the right side the band has the shape of a lindworm, a snake-like dragon figure, while on the left a band moves down and up the front leg, and ends on the belly of the lion.

The shelling of the harbour in 1687, the damage from the ropes for moving the lions, and later weathering, including damage from acid rain, have conspired to make the reading of the inscriptions very hard. Many runes are missing or only discernable with difficulty.

What do the runes say?

Several scholars have tried to decipher the runes over the last two centuries. The first was the Danish C. C. Rafn, who published his reading in 1857. Later, the Swedish runologists Erik Brate did a reading, and ultimately the Swedish scholar Thorgunn Snædal in 2014.

Many earlier attempts tried to read the inscriptions as a single text. By filling out the holes they arrived at complete but sometimes fanciful translations, which then differ wildly. In that respect, the more recent study by Snædal seems far more convincing.

The following are Snædal’s readings. She identifies three different writings, based on stylistic differences, which also leads to different datings. The three inscriptions are therefore probably not made together or by the same men.

Left side, on front leg and belly, from the early 1000s:

… they carved (the runes), the half (of the men) … and in this port, these men cut runes after Horse the farmer … Svear took care of this on the lion. (He) fell before he could collect tribute/get paid.

Thorgunn Snædal, Runinskrifterna på Pireuslejonet i Venedig, 2014, pp. 14-24.

Left side, on hind leg, from the 1000s:

Young warriors carved the runes

ibid., pp. 24-25.

Right side, from the 1000s:

Åsmund carved … these runes they Eskil/Askel … … Torlev(?) and …

Ibid., pp. 25-32.

This last inscription is quite long, but very damaged, which is why the translated fragments appear short.

What did Vikings do in Greece?

So Scandinavian Vikings carved runes on the lion while it stood in Piraeus near Athens, in the eleventh century.

Why were they there, so far from Scandinavia?

While many Vikings from Denmark and Norway went west, to England, Ireland, Normandy, Iceland, Greenland and North America, many Vikings from Sweden went ‘rus’ – to the east.

Navigating the rivers and lakes of what is now the Baltic countries, Russia, Belarus and Ucraine, they made it all the way to the Black Sea and Constantinople, well before the year 1000.

After some incomprehensions with the Byzantines, they learned to communicate, and one of the results was the Varangian guard. The Roman Emperor of Constantinople (which the Scandinavians called Miklagard) hired Vikings, mostly from Sweden, to serve as an imperial bodyguard, but many also served in the Byzantine navy and army.

In the 900s, Byzantium still controlled some territories in Southern Italy, and Viking troops fought there. In the mid-1000s Norman invaders arrived in Sicily and Southern Italy, where they established dominions, so the Varangian Vikings could find themselves opposed to descendants of Vikings from Normandy, in the middle of the Mediterranean.

Several runic inscriptions in Sweden mention Miklagard, Greeks in general, and the land of the Lombards, which wasn’t Lombardy but the Lombard Duchy of Benevento in Southern Italy.

We know from Byzantine sources that members of the Varangian guard were in Piraeus on several occasions over more than a century, so there have been plenty of opportunities to leave their marks on the lion. Since many Vikings served in the Byzantine navy, they would naturally have spent time in the harbour.

Many have tried to connect the runes on the lion in Venice with known historical figures, such as Harald Hardrada who served in Byzantium 1033-43, but none are very convincing.

A short summary

We’ve been a bit around, so let’s try to pull everything together.

Scandinavian, mostly Swedish, Vikings served the Byzantine Empire in the eleventh century, and stationed in the harbour of Piraeus in Greece on several occasions, they carved several runic inscriptions on an ancient statue.

During one of the many wars between Venice and the Ottoman Turks, the Venetians conquered Athens in 1687, and hauled the two ancient lion statues to Venice, where they still are.

The war and later transport damaged the runes, and they remain very hard to read. They were only discovered at the end of the 1700s.

There are many interpretations of the runes, because of the damage, but there is no doubt they’re made by Vikings.

References

- C.C. Rafn, En nordisk Runeinskrift i Piræus, Antiquarisk Tidskrift, 1857.

- Thorgunn Snædal, Runinskrifterna på Pireuslejonet i Venedig, Riksantikvarieämbetet, Sweden, 2014. Available as PDF / CC.

- Runinskrifterna på Pireuslejonet i Venedig (Pro Venezia Sverige), published online 2015.

A few more photos

Related articles

- Long live the doge

- An ancient game board in Venice

- The mysterious hooks of fortune at San Canciano

- State institutions of the Republic of Venice

- Doges of Venice

Leave a Reply