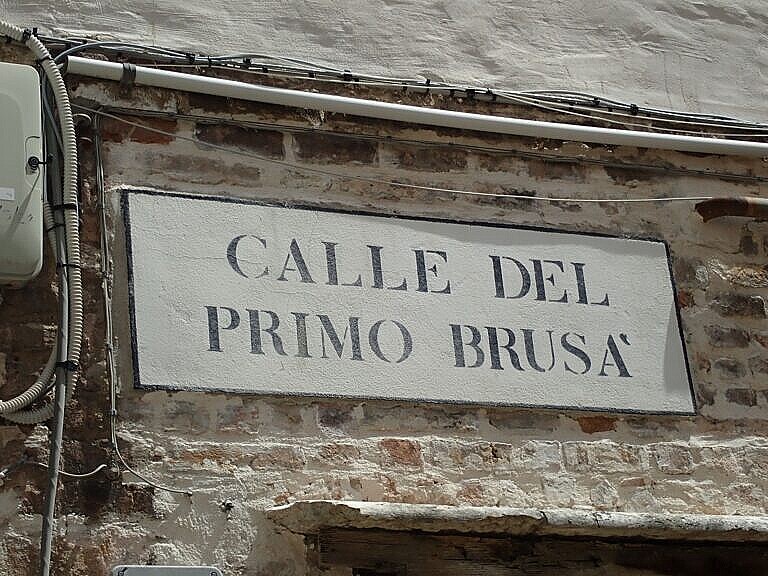

In the Castello sestiere a small alleyway has a name that poses more questions than it answers. It is the Calle del Primo Brusà, literally the alleyway of the first fire. The next alleyway along the Barbaria de le Tole is the Calle del Secondo Brusà.

From the names alone we can deduce that there were two distinct fires, very close to each other.

The place to find answers to such questions is the book Curiosità Veneziane by Giuseppe Tassini (1827-1899). First published in 1863, it is still being reprinted regularly. According to the publisher it is still a bit of a best-seller, even after a century and a half.

Curiosità Veneziane lists almost all the place names present in Venice in the mid 1800s. There are explanations and many odd stories from the documents in the archives where Tassini spent much of his time.

The first fire (1683)

Tassini tells us that the first fire broke out in September 1683, when a large crowd had gathered in the area around Barberia de le Tole.

The gathering and the celebrations had two reasons, which were probably interconnected.

Firstly, the Ottoman Turks had besieged Vienna, the capital of the Austrian empire, for several months that summer. On September 12th the Austrians together with troops from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth defeated the Turks in the Battle of Vienna. This battle put an end to Turkish advances into Western Europe, and eventually turned the Austrian Empire into Austria-Hungary.

The same Ottoman Turks were the historic enemy of the Venetian Republic. Venice had fought, and mostly lost, wars with the Turks for over two centuries.

Secondly, on August 11th, Pope Innocent XI had declared 1683 an extraordinary Jubilee year.

That meant Catholics, who did the right acts of penitence, could receive complete absolution of all their sins.

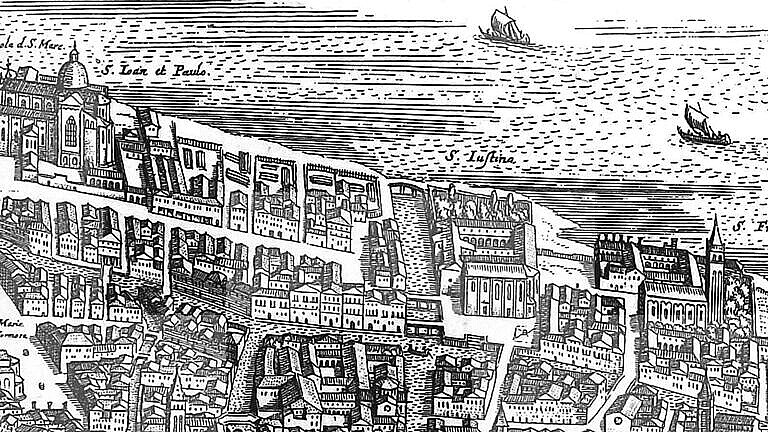

It might be relevant here that Barbaria de le Tole is the main road connecting the church of San Francesco della Vigna, and the Basilica di SS Giovanni e Paolo.

San Francesco della Vigna was the seat of the papal delegate (ambassador) to Venice. It would definitely have played a role in the Jubilee year. The Basilica di SS Giovanni e Paolo was (and still is) one of the most important churches on Venice.

We don’t know how and why the fire broke out, but with lots of people crowding the narrow alleyways, it doesn’t take a lot. Furthermore, if people were massing in the streets after dark, many would have carried lamps and torches. There was no public illumination then.

The second fire (1686)

The other for started in a storage room for timber, in June 2nd, 1686.

Timber tradesmen used the area around Barbaria de le Tole as far back as we know. They used the shallow area on the north side of the road for seasoning the wood by immersion.

The word “tole” refers to the planks. The Venetian word “tole” (plank) derives from the Latin “tabula”, which is also the origin of the English “table”. The word also appears in the Rio de la Toletta, which has nothing to do with toilets.

This second fire was far more devastating. Tassini says it destroyed all buildings from the Ospedaletto to the Church of Santa Maria del Pianto, and even some houses down to the Rio di San Giuseppe in Laterano. That’s an area about 250m across.

According to popular legend, only one building survived the fire in this area. It had an altar with an image of St Anthony of Padova on the façade, so people attributed him with the miracle.

Common fear of fire

How come the fires are remembered through the names of two alleyways, more than three centuries later?

It is evident from the references in Curiosità Veneziane that the two fires soon became part of the Venetians’ collective memory.

Tassini cites a couple of texts from the late 1700s about the solitary surviving house. People remembered the two fires for a long time.

Part of the reason is simply that Venice is a very densely build city of highly inflammable buildings. There’s a lot of wood inside Venetian houses, to keep the structure as light as possible.

Fire therefore scared most people. If a fire broke out, it would almost inevitably spread fast, given how the houses lean on each other and how narrow many of the alleyways are.

The fire hazard was very real. Heating and cooking were generally by open fire in a fireplace. Likewise lighting was by candles or oil lamps. Lots of open fire doesn’t exactly reduce the risk of fires.

Fire prevention laws obliged people to put the fire out or cover it up before they went to bed. Being aware of the fire hazard was therefore very much a part of daily life.

It is not odd that people would remember two large fires, in the same area, with just three years in-between.

Why street names?

Street names in the time of the Serenissima primary served the purpose of being able to explain where something was.

Common people didn’t have addresses as such, as there was no general mail service before the early 1800s. Likewise, the state didn’t imposes addresses on people, because the Venetian Republic didn’t levy property taxes.

Consequently, the names of alleyways and streets in Venice where simply whatever people called them. Their main purpose was to be able to give directions. This also explains why there are so many repeat names all over the city.

The psychological impact of two major fires, very close both in time and in space, probably meant that the Venetians starting to use the two fires to explain where things were in the city, to give directions.

Hence, the “first fire” and the “second fire” slowly became commonly used place names. When the Venetians started painting the names on the walls—giving rise to the nizioleti—the expressions ended on the street signs we see today.

Today

Even today, over three hundred years later, there are still signs of the fire in the area.

At the Calle del Primo Brusà there’s a one storey building, which is not a good way of capitalising your property in a city like Venice where space is scarce. However, by looking at the neighbouring building, we see that there are no windows there, except in the back on the internal courtyard. Clearly the one storey building has been higher once. It is therefore not unlikely that it was damaged by one of the fires, and never fully rebuilt.

The Palazzo Morosini has a private garden behind a tall wall. That garden might very well be a result of the fires. Once the houses behind the palace’s courtyard had burnt, the owners of the palace had an opportunity to get a garden, which was quite a status symbol in such a space starved city.

Notes

The painting at the top of this page is not one of the fires in Barbaria de le Tole, because I haven’t been able to find any such picture. It is a painting by Francesco Guardi of a huge fire at San Marcuola in 1789, of which he made a whole series of paintings and drawings.

Bibliography

Tassini, Giuseppe. Curiosità Veneziane ovvero Origini delle denominazioni stradali di Venezia. 1863.

Leave a Reply