Several recent Venetian Stories and many other posts on the web site have touched on legal issues: laws around prostitution and fun loving nuns, but also issues like legal protections for inventors and just keeping order in general.

Venetian Stories

This post is an issue of our newsletter — Venetian Stories — which goes out every few weeks, to keep in touch and share stories and titbits from and about Venice and its history.

One particularity shared by these stories is that the people and institutions making the laws were the same as those who enforced the laws and who judged transgressions of the same laws.

The three branches of government — the executive, the legislative and the judiciary — existed in the Republic of Venice. They weren’t, however, separated.

The Council of Ten

The much feared Council dei Dieci (Council of Ten) is an example of a Venetian state institution with powers in all three branches of government.

The Consiglio dei Dieci was for much of the history of Venice a powerful institution. The Consiglio Maggiore created it shortly after a failed coup attempt — the Baiamonte Tiepolo conspiracy in 1310 — to find and bring the conspirators to justice.

The Council of Ten consisted of ten patricians — noblemen — elected for one year at a time by the Maggior Consiglio, which was the highest authority of the Venetian state. As was customary, the Doge and his six Councillors (the Serenissima Signoria) presided over the council, so the Council of Ten actually had seventeen members.

It had many and varied competences.

Most importantly the Council of Ten was in charge of the security of the state from internal enemies, so it was in effect a secret service. However, it also had normal policing functions, such as the control and authorisation of arms in private hands and issues of blasphemy and immorality.

The Council of Ten sat as a court. It heard cases of crimes against the state, and it became the sole arbiter in all cases against patricians.

Administratively, it supervised economic sectors like glass making, forestry and timber, and mining. These sectors had particular importance for the state, and hence they ended under the auspices of the Council of Ten.

The Council of Ten managed its own budget internally, and had a dedicated armoury within the Doge’s Palace.

The importance of the Ten made them automatic voting members of the Pregadi (the Venetian Senate), which was one of the main (predominantly) legislative organs of the Venetian state.

The wide ranging powers of the Council, combined with the inherent secrecy surrounding it, made it a feared institution, also amongst common people.

Mantis shrimp

The members of the Council of Ten wore a black toga as symbol of their status and power. However, the monthly elected Cai (Heads) of the council, who were even more powerful, wore a purple toga with a red stole.

Consequently, people called them Canoce col coral, which literally means a mantis shrimp with eggs. The mantis shrimp is pink/violet in colour, and the eggs are bright red.

It is natural to counter fear of something by ridicule, and people generally feared the Cai del Consiglio dei Dieci.

Separation of powers in Venice

If we try to squeeze the Republic of Venice into a modern constitutional model of a tripartite state, we’ll end up with the Doge and his council as executive, the Maggior Consiglio and the Pregadi as legislative, and the Consiglio dei Dieci and the Quarantia as judiciary.

However, it doesn’t work.

The ‘government’ or ‘executive’, in the form of the Doge and the Signoria, were integral part of the Council of Ten, so that would have to be part of the executive branch.

However, the council sat as a court on several matters, so it was judiciary.

The members of the Council of Ten were also, in their function as councillors, voting members of the Pregadi or Senate, so they also had legislative powers.

In short, the Venetian state didn’t operate like that.

Not just the Council of Ten

Now the Council of Ten could be some odd one of a kind institution in the Venetian system, but it wasn’t.

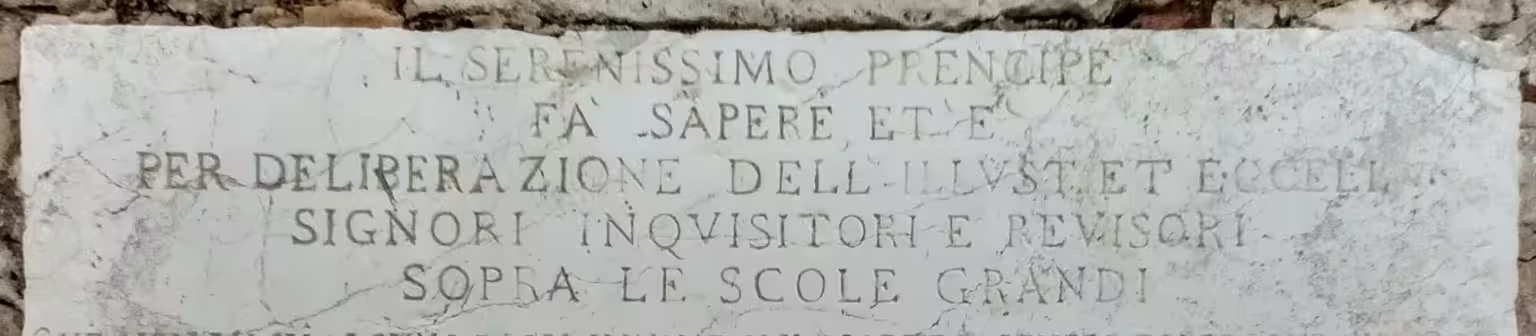

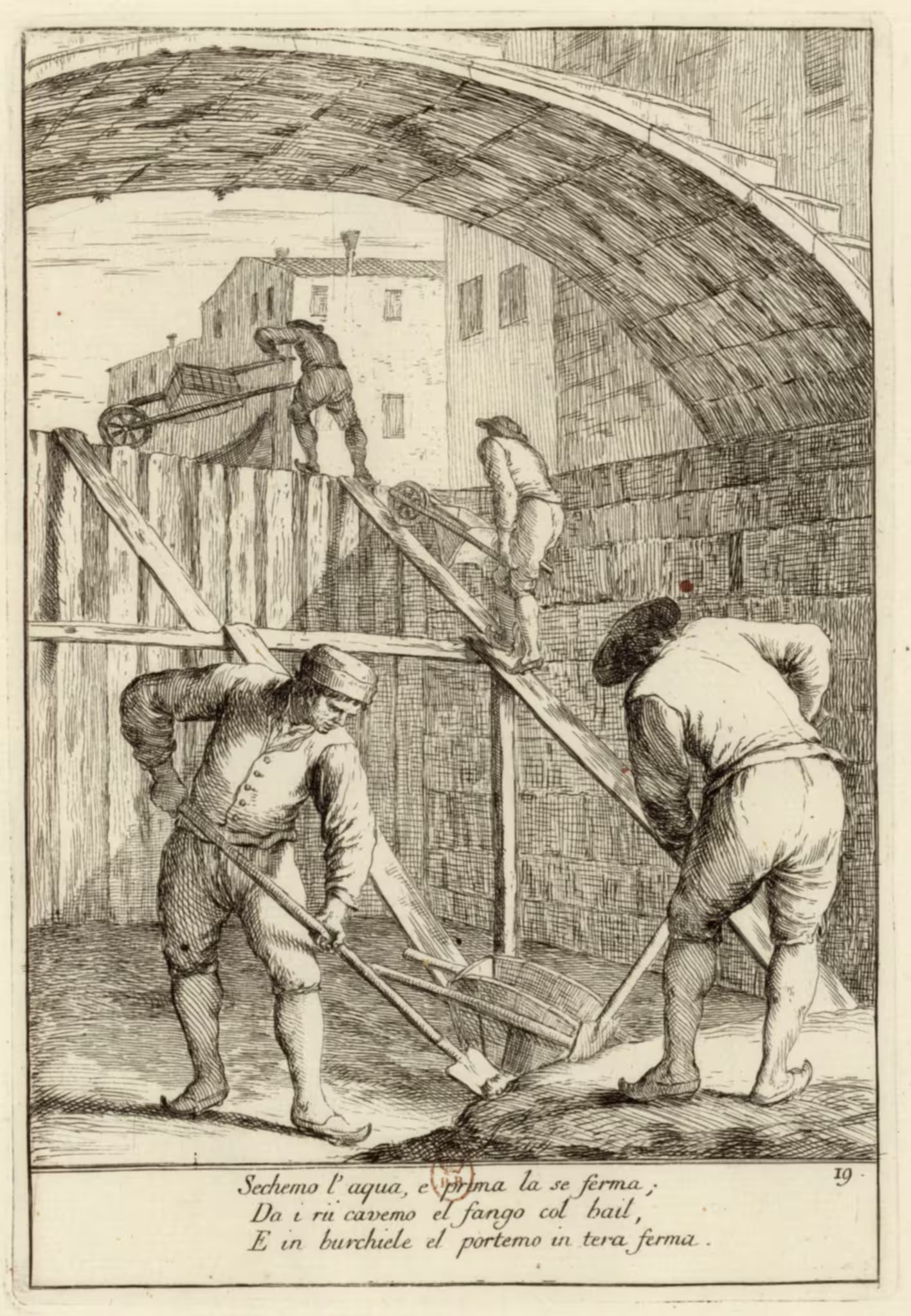

The office of the Eccellentissimo e Illustrissimo Signori Inquisitori e Revisori sopra le Scuole Grandi (The Most Excellent and Most Illustrious Lords Inquisitors and Accountants over the Great Schools) — titles have to sound good too — were three auditors of the Scuole Grandi. In daily usage they were just the Inquisitori sopra le Scuole Grandi.

The Scuole Grandi were charities — immensely wealthy institutions which nobody really owned, not unlike some major charitable foundations in our times. The manages of such institutions could easily use their control over the wealth of the institution for personal gain. The Venetian state, therefore, appointed auditors to curb such abuses.

A decidedly marginal administrative institution within a complex state like the Republic of Venice.

Yet this office of three patricians could make laws of the state within their remit. They could also hear cases of breaches of such laws, and they could sentence wrong-doers to punishments such as fines, public ridicule (the stock), flogging, forced labour in the navy docks and death by hanging.

The Inquisitori sopra le Scuole Grandi too were executive, legislative and judiciary rolled into one.

The tripartite state

Montesquieu is usually credited with the idea of the tripartite state, i.e., that a state should have the three distinct branches of government — executive, legislative and judiciary — and that these three parts of the state should be independent of each other, and be able to curb the excesses of the other branches.

Some of these ideas were, however, already circulating before Montesquieu wrote his Esprit des lois in 1748. Separation of executive and legislative was a hot topic in England during the Commonwealth and also after the Restoration in the late 1600s.

The idea spread wider than that. The first place where such a tripartite system is implemented in a constitutional document is in an early Zaporozhian (Ukrainian) pact from 1710.

These early ideas became dominant with the American and the French revolutions.

The Venetian Constitution

The issue here is obviously one of chronology. The Venetian state started long before anybody had thought about the separation of powers.

The Venetian state had its roots in late Antiquity, within the Italian dominions of the Byzantine empire, so it had a Dux, which was a Byzantine title. Many of the early Doges also held titles like Hypatos, Spatharios and Protosebastos which were all Byzantine honorary titles given to them by the emperor in Constantinople.

When the Venetians started electing the Dux, later the Doge, themselves, they created the Concio — an informal assembly of the people — to elect the Doge.

From here on institutions were created, changed, abandoned and dismantled continuously over the centuries, as new needs arose and power balances shifted.

Most of the central institutions of the Republic of Venice appeared in the late 1100s, the 1200s and the early 1300s, but the system never stopped changing.

Even central and important institutions like the Concio could be emptied of functions and later dissolved, and other newer organs, like the Maggior Consiglio could take over many of its functions.

The Council of Ten — which was an extremely powerful organisation — was created by the Maggior Consiglio to resolve a specific task of catching the conspirators of 1310. Once there, it stayed.

All these fundamental changes to the structure of the state — the Maggior Consiglio usurping the powers of the Concio, the creation of a powerful secret police, and many others — happened without any formal basis in a constitution.

The end

When the Republic of Venice had no way of preventing Napoleon from conquering it in May 1797, the Maggior Consiglio met in the Doge’s Palace. They had a debate, they voted casting their balote in an urn, and they decided by a slim majority to dissolve themselves.

Following the dissolution of the Maggior Consiglio, the last doge, Ludovico Manin, abdicated. His authority rested on the consensus of the Maggior Consiglio which no longer existed. No new doge could be elected, for the same reason.

The two central institutions of the Venetian state had removed themselves, and consequently the Republic of Venice was no more.

There was no formal constitutional basis for all this because there was no formal constitution.

The Venetian nobility simply made it up as they went.

Related articles

- State institutions of the Republic of Venice

- Chronology of major Venetian state institutions

- The ASV Indice by Andrea da Mosto

- Consiglio dei Dieci — ASV Indice

- Inquisitori alle Scuole Grandi — Lessico Veneto

- The Fall of Venice

- Ballot and ballottaggio

- However, we’ll make another — newsletter

Leave a Reply