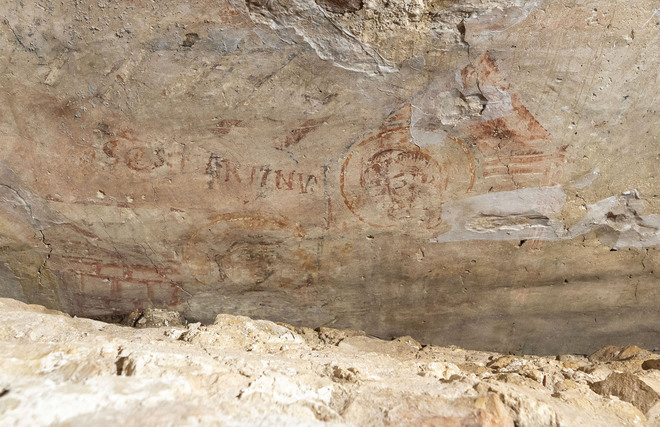

Recent maintenance work on the Santa Maria Assunta basilica has uncovered ‘new’ frescoes. Hitherto unknown, they can throw some fresh light on the earliest history of Venice.

The ‘new’ frescos are from the 800s and 900s so they are actually quite old. The frescoes appear on the side walls, above the current ceiling, which dates to the early 1000s. They are not visible from inside the church.

The space above the arched ceiling was full of debris. When the workers removed this debris to check for infiltrations of rain water, fragments of old frescoes appeared.

Mosaics and frescoes

The church of Santa Maria Assunta dates from the 600s. Invading armies forced the bishop of the Roman city of Altino to flee, and he settled at Torcello. The Exarch of Ravenna, who governed the area on behalf of the Byzantine emperor in Constantinople, later authorised the move.

The oldest parts of the church is from this period after 639 CE, but little remains.

In 836 CE the church was enlarged to its current size, though it would probably have appeared quite different.

The church finally got it’s current appearance in 1008 CE, when it was restructured and decorated with the splendid Byzantine mosaics we can still admire now.

The rediscover frescoes are from the middle period, before the mosaics and the arched ceiling.

The frescoes are not Byzantine in style, like first church and the mosaics of the current church. They are Carolingian, in style and in message.

The political contest

A fragment of text mentions St Martin, who was a western saint, venerated in the Carolingian empire, but not in Constantinople.

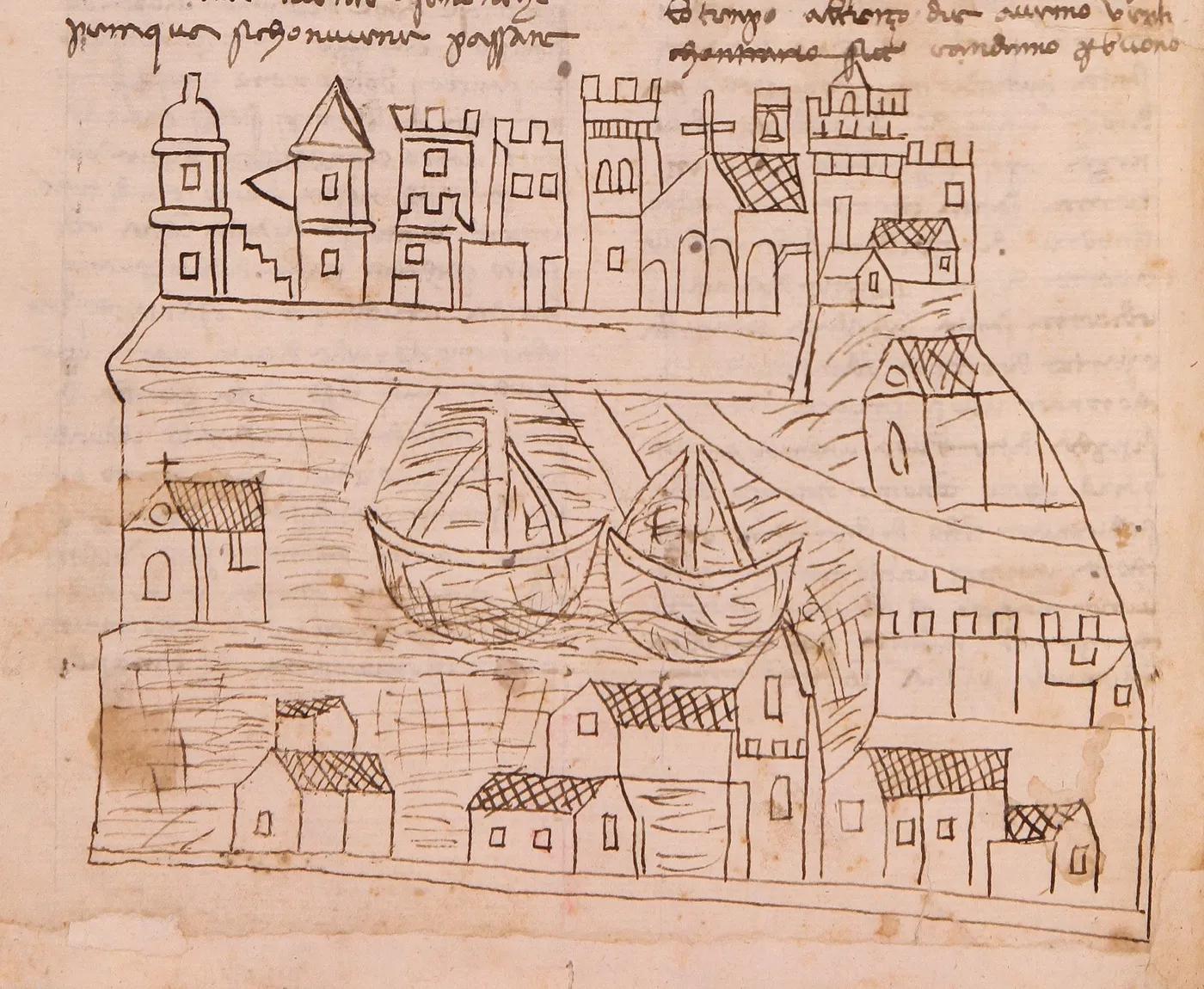

Torcello, the church, and indeed the origins of the entire Ducato di Venezia, goes back to the 600s and 700s. This was a time when the Byzantine empire still controlled the parts of NE Italy.

In the 700s and 800s, the Carolingian empire expanded into the Italian peninsula, and took control of the territory bordering the lagoon. They even tried to invade the lagoon, and burned down the doge’s residence at Malamocco in 811 CE. This caused the doge to move to what is now the city of Venice.

The Byzantine empire had not, however, given up on Italy yet, and continued to try to exert control over Venice.

The nascent Venetian state now found itself in a squeeze. On the mainland they had the Carolingian empire, while along their trade routes east they had the Byzantine empire. Both of these demanded the allegiance of Venice.

This was before many of the political and administrative structures of the Serenissima existed, and the state was run by varying factions and alliances of wealthy families.

Some factions preferred an alliance with the Carolingians, while others wanted to be on the side of Byzantium.

The political balance within Venice shifted back and forth, and often violently so. Quite a few doges met a premature death. Many others found themselves imprisoned or confined to a monastery, often blinded or maimed in other ways.

Over time, as the political situation on the Italian peninsula became ever more unstable, the Venetians gradually converged on the Byzantine side. They decided to focus on the sea and on trade.

The church of Torcello as a mirror

The church of Torcello reflects all these political shifts back and forth between the two super powers of the time.

The first church, built by a local bishop with the permission from the Exarch of Ravenna, was Byzantine in style, like many of the contemporary churches in Ravenna.

The second church had Carolingian frescoes, while the third had (and has) Byzantine mosaics.

In the early Middle Ages Torcello was as important as Venice, if not more so. The decoration of the cathedral, seat of the bishop, was no small matter.

Leave a Reply