The image of the plague doctor is so ubiquitous it has become a part of the image of Venice.

Venetian Stories

This post is an issue of our newsletter — Venetian Stories — which goes out every few weeks, to keep in touch and share stories and titbits from and about Venice and its history.

We do not, however, have any sources connecting such a figure with Venice. As in, we do not have any sources connecting the plague doctor with Venice.

The plague doctor therefore wasn’t Venetian, if he ever existed at all.

Just to be certain, I’m talking about this guy.

This watercolour, by Giovanni Grevembroch, is from around 1750. It is the first Venetian depiction of the plague doctor figure that I am aware of.

The shortest history of the plague

The black plague came to Venice and Western Europe in 1347–48, and it was endemic for the next several centuries.

Recurring waves of the decease killed about half the population of much of Europe within the first fifty years.

The medical ideas of the period did not allow for a proper understanding of how the contagion spread, much less find a cure for the decease. Without any kind of effective treatment, the only possible approach to govern the plague was prevention.

The Venetians came up with the idea of lazzaretti in the 1400s, initially for isolating the sick, and later for quarantining those suspected of carrying the contagion as well.

Through such innovations of prevention, the Europeans gradually learned to coexist with the plague.

The repeated outbreaks in the 1300s and 1400s gave way to a period where strict preventive measures mostly prevented the spread of the contagion. When outbreaks did occur, swift intervention could often contain them.

The last major epidemics in Venice were in 1575–1577 and 1630–1631, while Rome and Naples were hit in 1656. The last large-scale outbreak was in Marseilles in 1720.

The plague in Verona of 1630

It so happens, that we have an eyewitness testimony of the plague in Verona in 1630. Not only that, but we have it from a medico di collegio — an official doctor of the city.

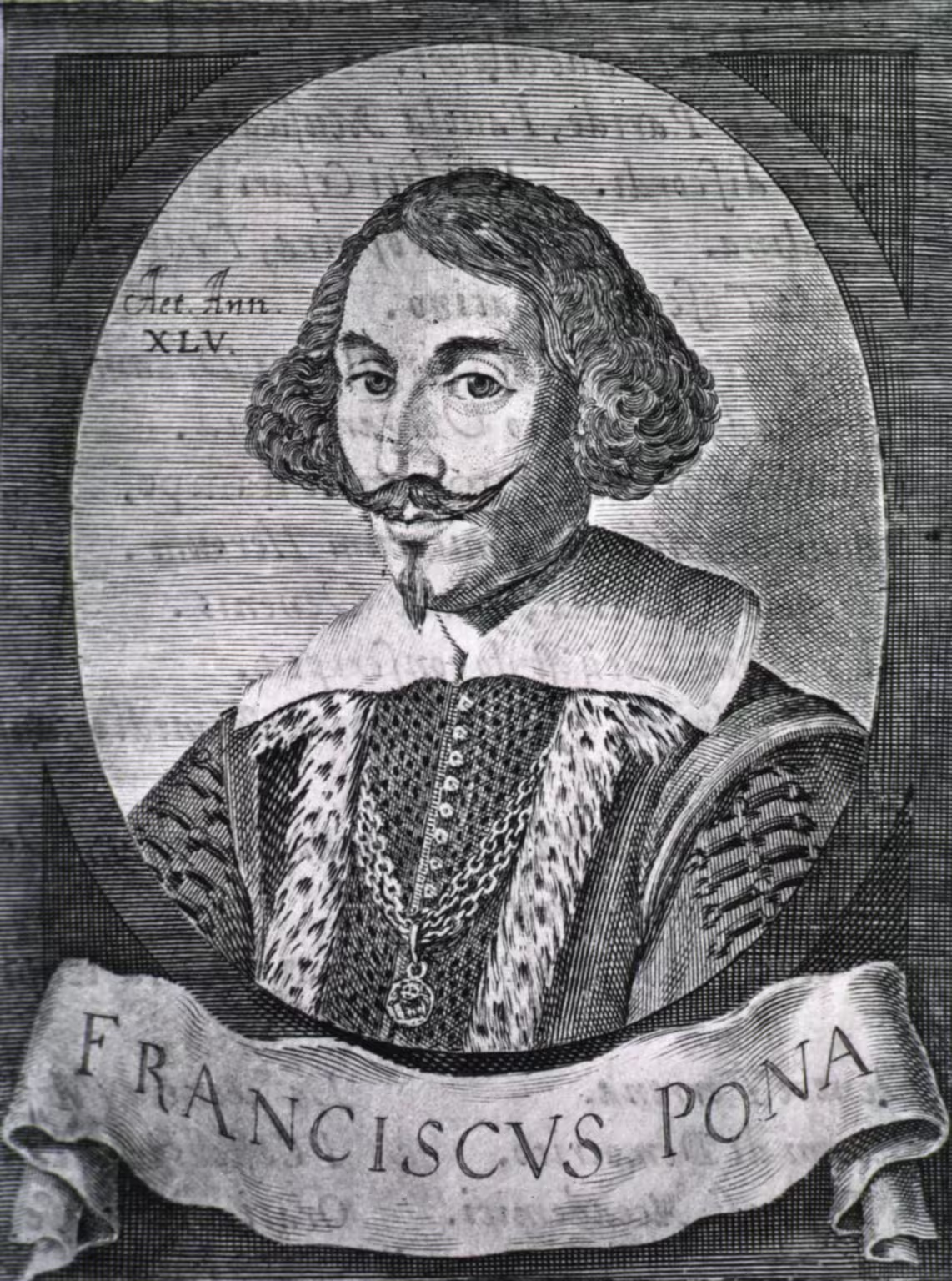

Francesco Pona had studied medicine at the University of Padova — one of the most esteemed seats of medical learning of the time. He was also a philosopher and an author who mingled with the highest echelons of Venetian cultured society.

Pona described how the plague came to the city through soldiers who had fought in the war of succession in the Duchy of Mantua, and how it spread through the city, causing over half of the population to either die of the plague or flee the city.

It is a tale of death, misery, unburied cadavers ditched in the river, and people dying in the streets, as the authorities desperately tried to regain control of the situation.

Francesco Pona was one of the very few surviving doctors. He had a wife and small children, and he locked the entire family up in their house for two months, only speaking to people from an upper window.

Practically all the doctors who went around the houses to see to plague stricken patients, died of the decease. Likewise, all the doctors who served in the Lazzaretto of the city.

After listing all the names of his dead colleagues, Pona made this reflection:

The City of Lucca, following the custom of the French Doctors, in this same evil influence, established that the appointed Doctors should dress in a long cloak, of thin waxed cloth, and that, hooded in the same, with crystals before their eyes, they approached the infected. Thus, the path to contagion is less obvious; because the malignant breath does not have such an easy opening through which it can creep in and be attracted through breathing. I suppose, following this advice, the use of medicinal vinegars; of odoriferous herbs, of proportioned antidotes.

The city of Lucca was in the Duchy of Tuscany, which was another country. France was then, like today, yet another foreign country.

It is evident from the description that the doctors of Verona didn’t wear protective cloaks of waxed canvas, with a hood with crystal goggles. If they had, Pona wouldn’t have made such a comparison with two other states.

Francesco Pona was a part of the intellectual literary elite of Venice, and Venice sent help to Verona during the epidemic. Had such protective cloaks and hoods been in use in Venice, they would no doubt have made their way to Verona.

Consequently, such suits were not used in Venice in 1630.

Later rules and regulations

Venice, and its dominion which Verona was part of, were badly hit by the epidemic of 1630–1631. Around one third of the population died.

When the plague struck in Rome and Naples in 1656, all the alarm bells went off in Venice. The state could not afford a second bloodletting like twenty-five years earlier.

The Magistrato alla Sanità — the Magistracy of Public Health — started printing a collection of several terminazioni, or decrees, in matters of plague prevention. The resulting forty-page booklet was henceforth given to each new manager of one of the Venetian lazzaretti, for which they had to sign a receipt in front of the notary of the magistracy. The booklet was reprinted numerous times, well into the mid-1700s.

Clearly, the authorities wanted these rules followed.

The booklet is full of quite detailed instructions to the priore (manager) of the lazzaretti. All sorts of practical, and no doubt recurrent, issues are covered.

The doctor is mentioned exactly once:

When somebody dies in the lazzaretti, the priors shall immediately give notice to the Office, and not permit that the bodies are buried, or touched by anybody whatsoever, if they haven’t been seen first by the Doctor of the Magistracy …

This instruction manual for the priors of the Venetian lazzaretti was used until the end of the Republic, and the raven-like doctor in his black cloak and beaked mask was not part of it.

404 Doctor Not Found

It is very unlikely that the well-known figure of the plague doctor was ever a common sight in Venice, in times of plague or not.

There are no traces of the figure in Venetian art, and there’s no trace of it in the written sources.

Of the many contemporary works of art from Venice and its dominions, none depict the cloaked and beaked doctor. Given how iconic the raven-like black figure is, this is an unbelievable omission.

Francesco Pona was a doctor. He was the one who was supposed to wear the outfit, yet neither he nor any of the other doctors in Verona did so. What they knew about the figure was little more than hear-say from far-away countries.

The only Venetian image of the plague doctor is the water-colour above, from well over a century after the last epidemic. Furthermore, in the notes to the painting, Grevembroch made it clear that it was not a figure he had seen, but one he reproduced from other sources as a curiosity.

In short, there was no cloaked, hooded black raven in Venice in the times of the Venetian Republic.

Bibliography

Grevembroch, Giovanni. Gli abiti de veneziani di quasi ogni eta con diligenza raccolti e dipinti nel secolo XVIII, orig. c. 1754. Venezia, Filippi Editore, 1981.

Magistrato alla Sanità. Capitoli Da osservarsi nelli Lazaretti Stabiliti, e decretati Dagl’Illustrissimi, & Eccellentissimi Signori Sopraproveditori, Aggionti, e Proveditori alla Sanità. Venezia, 1674.

Pona, Francesco. Il gran contagio di Verona nel milleseicento, e trenta. Descritto da Francesco Pona. In Verona per Bartolomio Merlo. Stampator camerale, 1631.

Leave a Reply