The Fortress of Sant’Andrea — in the Venetian lagoon not far from Venice — is a unique example of Renaissance military architecture and engineering. It is also a show-piece, to put the might and wealth of the Venetian state on display for everybody to see.

The fortress was a part of the defences of Venice from a surprise naval attack, and later ongoing conflicts with the Ottoman Turks kept the fear of naval incursions into the lagoon alive.

The importance of the lagoon

The Venetians always had parts of the lagoon fortified.

For much of the history of Venice, the territory of the Venetian state was the lagoon — the Dogado from Grado to Cavarzere. Venice didn’t acquire substantial territories on the mainland until the early 1400s, and even after that, the lagoon area always was the heartland of the state.

The largest risk was always that of a fast naval incursion at San Nicolò, which is just a few kilometres from central Venice and the governmental area of San Marco.

The location of the Fortress of Sant’Andrea is three kilometres east of Venice in line of flight. Along the main canals in the lagoon, the distance is about five kilometres.

Venice needed access to the sea for trade. However, the proximity was also a liability, and Venice had been attacked before from that side. The Festa delle Marie, which was celebrated annually until the late 1300s, remembered such a raid on Venice in the 900s.

In fact, in 1313 there was an observation tower on the island, which is now called La Certosa. Back then that island was usually called Sant’Andrea due to the important church dedicated to St Andrew on the island.

The Genovese and the Turks

Venice had been competing with Genoa for control of the lucrative sea trade between the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Europe since the early Middle Ages, and they fought numerous wars over these economic interests.

During the War of Chioggia (1379–81) a Genovese navy entered the Venetian lagoon from the south, thereby threatening the very existence of the Venetian state. The Genovese and the Venetians fought a series of naval battles inside the lagoon, in an area easily visible from the Palazzo Ducale.

Venice prevailed, but for a while, they had their back against the wall. The War of Chioggia was an existential fight for Venice.

As the threat to Venice from Genoa waned, the Ottoman Empire grew, and the Turks became the main threat to Venetian interests.

The medieval fortress

After the War of Chioggia it was evident that the lagoon needed better fortifications.

The existing fortifications on the side of the Lido had been reinforced during the war, but after the war they were considered insufficient.

The Maggior Consiglio — the highest authority of the Venetian state — decided in 1400 to reinforce the fortifications on the Lido side, and to build an opposing fortress on the opposite side of the canal leading from the sea towards Venice.

The existing fortress on the Lido became henceforth known as Castel Vecchio, and the new fortress as Castel Nuovo. Together, they were li do castei — the two castles.

The Pregadi — the Venetian Senate — elaborated on the decision in 1401. They specified, among other things, the need for a chain across the canal to physically block the passage of enemy ships.

Building started in 1404, but was not finished in 1410, when the Senate inquired into the still unfinished project. The fortress must have been practically finished in 1413, however, as the surviving tower carries the coat of arms of Doge Michele Steno, who died that year.

The maschio of the medieval fortress — the central stronghold — still stands, as it was incorporated into later structures.

The rest of this first fortress is gone.

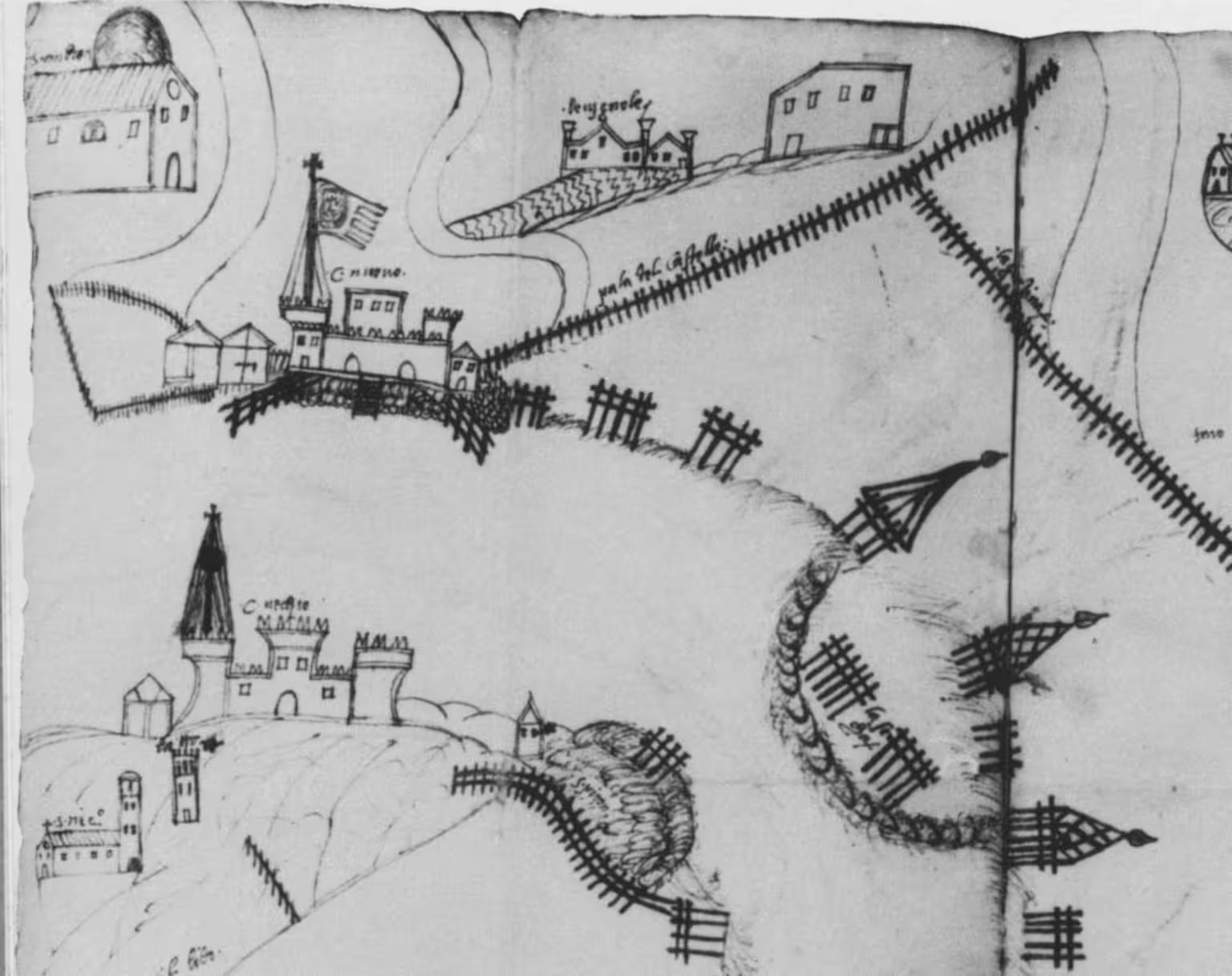

The only source for how it looked is a drawn map from 1526 of the harbour entrance. It shows the maschio, behind a wall with two gates, flanked by two smaller towers. On a flag post on the left tower flies the gonfalone — the Venetian flag with the lion of St Mark. Both in front of the fortress, and on the sides of the canal leading to the sea, wooden palisades control the passage of the ships.

Renewed urgency

The War of the League of Cambrai (1508–1516) started with everybody against the Venetians, who initially fought alone. The fight was never as desperate as it had been against Genoa, but it was still bad.

Consequently, the Venetian government decided to strengthen the defences of the lagoon. The worry was the same as ever, that a surprise attack from the sea could overrun Venice.

In 1534, the Council of Ten — whose main charge was the security of the state — asked Michele Sanmicheli to study the defences of the city and report back with a plan for improvements.

Sanmicheli was from Verona, a subject city of Venice, and renowned as an architect and military engineer. He reported back the following year, with a very detailed plan.

Other issues were more pressing, however, and Sanmicheli was sent to Dalmatia to oversee the construction of defences there. He returned to Venice in 1543.

Sanmicheli’s project for the fortress, now called Forte di Sant’Andrea rather than Castel Nuovo, received some modifications from the Venetian navy official Antonio da Castello, and building soon started. It went slower than planned, but in 1549 it was mostly finished.

Sanmicheli’s fortress

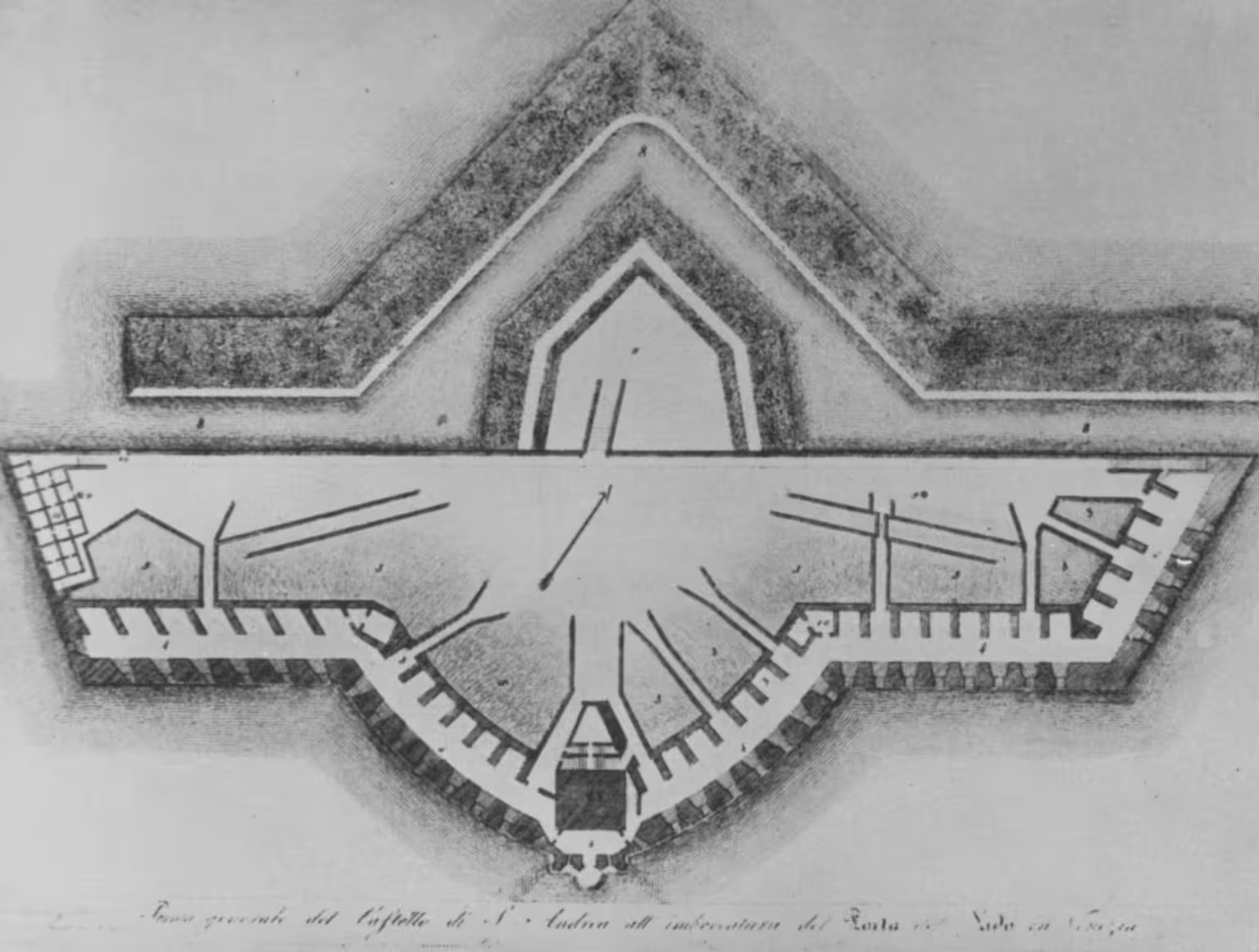

The project of Michele Sanmicheli and Antonio da Castello was for a fortress with enough guns to dominate not only the canal immediately in front of the fortress, and the approach to it from the sea, but also the narrow channel towards the lagoon on the other side of the Lido.

The central round bastion — in front of the medieval maschio — had a central gate for the chain spanning the canal, and positions for two large guns. Gun holes occupied the sides of the bastion and further down the flanks, some of which were double so they could fire in different directions, so the fortress could cover the entire range in front of it.

The new fortress had forty guns of different sizes at water level, so they could hit incoming ships in the adjacent canal with direct fire at their water line. It had another forty guns in barbotta — above the battlements — capable of controlling the canal on the other side of the Lido through indirect fire.

Sammicheli and the competition

Many factions within Venice and abroad had opposed the appointment of Sanmicheli. Even as the project proceeded, they kept spreading doubt about the validity and usefulness of Sanmicheli’s plan.

Giorgio Vasari, writing in 1568, described it this way:

Since this very large construction was brought to the end that has been said, some malicious and envious people said to the lordship that, even if it were very beautiful and made with all due considerations, it would nevertheless be useless in every need, and perhaps even harmful: because in discharging the artillery, due to the great quantity and size that the place required, could hardly fail to break apart and be ruined. Therefore, since it seemed to the prudence of those gentlemen that it was a good idea to clarify this, as it was something that was of great importance, they had a very large quantity of artillery brought in, and of the most enormous that were in the arsanal; and having filled all the gun positions above and below, and charged them even more than usual, they were fired at once: whereupon the noise, the thunder, and the earthquake that were felt were so great that it seemed as if the world had been broken, and the fortress with so many fires seemed like a volcano and an inferno: but not for long and the building remained in its same solidity and stability, and the Senate was very certain of the great value of Sanmichele, and the evil spirits were shamed and without judgment, those who put so much fear in everyone, that the pregnant gentlewomen, fearing something great, had left Venice.

Vasari (1568), part 3.2, p. 515–516.

The fortress passed the test, and what we have today is largely Sanmichele’s structure.

The Liberateur d’Italie in 1797

The guns at Sant’Andrea only ever fired once in anger.

As the tension between Napoleon and the Republic of Venice rose in 1796, the Council of Ten had banned all non-Venetian ships from entering the lagoon.

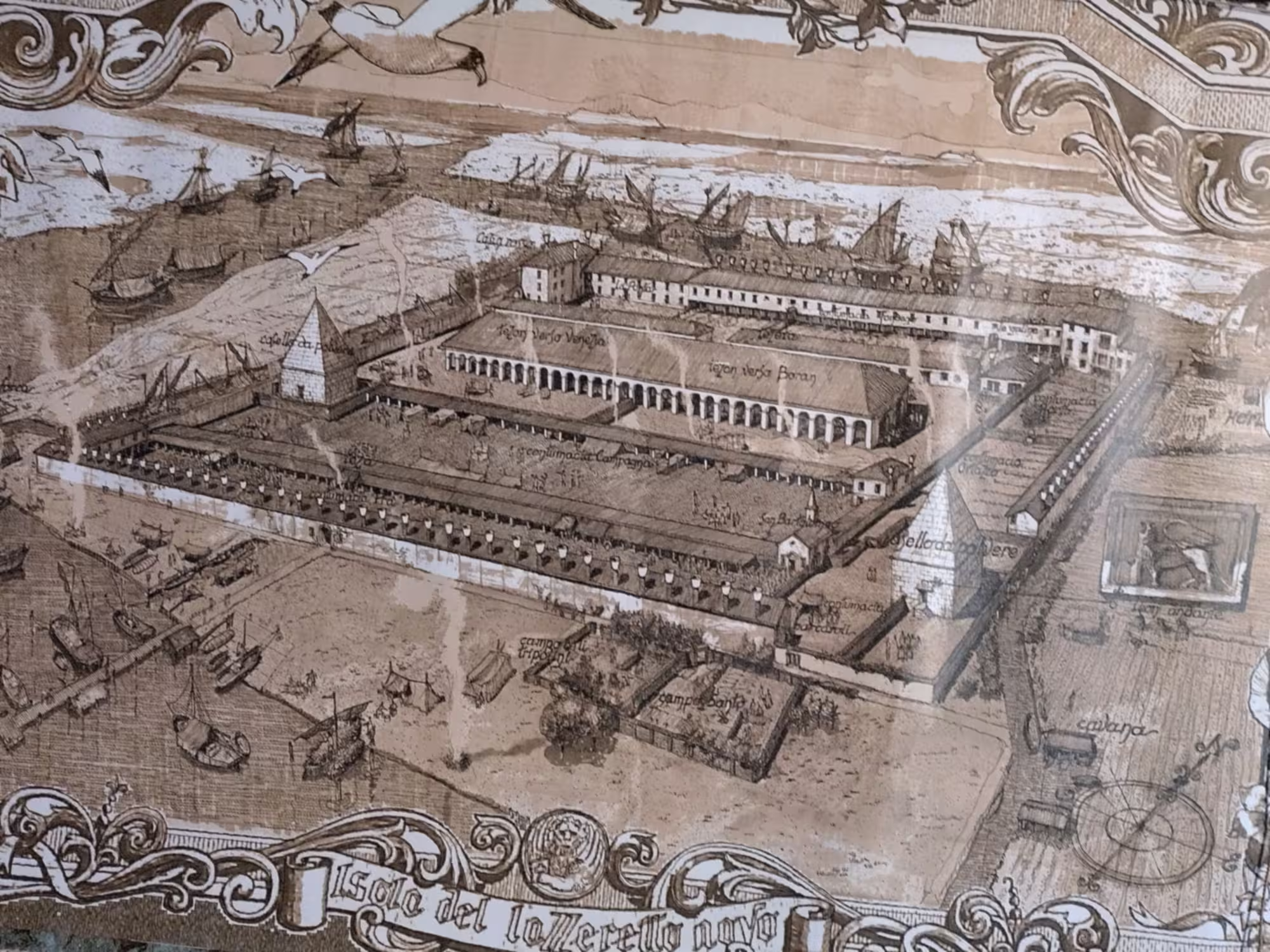

In times of peace, the guns of the Fortress of Sant’Andrea were kept in storage inside the Arsenale. So were the armoured rafts which served to keep up the chain over the canal between the fortresses of Sant’Andrea and of San Nicolò.

The fortresses were fully manned and armed, when, on April 20th, 1797, three ships flying the French flag entered the lagoon and approached the fortress.

Domenico Pizzamano, the commander of the fortress, ordered warning shots fired, which caused the two smaller vessels to turn around. The larger, the Liberateur d’Italie, under a French admiral, continued.

A small galley was sent to make the French ship turn around too, but they collided, and in the ensuing fight the French admiral was killed, along with several of the crew.

The commander sent a regular report to his superiors of the events.

Napoleon, who despised the Venetian aristocratic republic, was furious, and even more so as the killed admiral was a friend of his. He demanded the commander of the fortress arrested, which he was.

In the end, the Republic of Venice surrendered to Napoleon a few weeks later.

The shots fired from the Fortress of Sant’Andrea, and the fight on board the Liberateur d’Italie, were the armed defence the Republic of Venice could muster against Napoleon.

Abandonment and collapse

As a military structure, the Fortress of Sant’Andrea was superseded already in the early 1800s. The Torre Massimiliana on the nearby island of Sant’Erasmo — constructed in 1811–14 under the second French domination — could house much larger guns and thereby control the entire two kilometre wide bocca di porto.

The fortress remained a military asset, but it was far less important, and therefore saw less active maintenance.

Sediments of sand had been impeding traffic between the lagoon and the sea at San Nicolò for centuries. In the late 1800s, a solution to this problem was devised in the form of two long jetties protruding into the sea. By narrowing the opening from two kilometres to eight hundred metres, the jetties would both keep the sand from settling in the area, and force the tidal flows to run faster, whereby the canal would become deeper.

Considering the location of the Fortress of Sant’Andrea just after a bend of the flow, the increased power of the water put a lot of pressure on the 1500s foundations of the fortress.

In 1950, the entire right corner of the fortress collapsed into the water, leaving a gaping hole.

In the following decades, a modern series of cement boxes were lowered in front of the ancient foundations to prevent further erosion. Only in 1980 were the damages of the original collapse repaired, but — and this is almost needless to say, given the times we live in — at an artistic level much inferior to the lost original.

The Fortress of Sant’Andrea today

The Fortress of Sant’Andrea is still abandoned today.

The façade and the central tower have been restored and stabilised, but everything else has just been left as it is. Brambles grow all over, and are only removed to the extent volunteers go there to clean up every once in a while.

Until some years ago, a herd of goats roamed the island. When the weather was bad, they sought shelter on the stairways of the medieval maschio, where the steps were covered in a thick layer of goat shit. That has been cleaned up now, though.

It is possible to go there, for those who have a boat.

There are, however, absolutely no safety measures of any kind for visitors. Passages, stairways and platforms are without railings, and — needless to say — there are no provisions whatsoever for anybody with less than full mobility.

Yet, this is a major historical monument. It is a unique piece of medieval and renaissance military architecture, and it is the only place where shots were fired in defence of the Republic of Venice in May 1797.

Still, it is left to rot.

Bibliography

- Capolongo, Antonino and Marco Morin. Il forte di Sant'Andrea a Venezia : guida-itinerario. Venezia : Stamperia di Venezia, 1980. [more]

- Da Mosto, Andrea. Domenico Pizzamano in Nuovo Archivio Veneto, tomo 23, parte 1. Venezia, 1912. [more]

- Da Mosto, Andrea. Domenico Pizzamano marinaio : contributo per la storia della marineria veneziana nel secolo 18 in Nuovo Archivio Veneto, tomo 24, parte 1. Venezia, 1912. [more]

- Pietro Marchesi. Il Forte di Sant'Andrea a Venezia. Venezia: Stamperia Venezia editrice, 1978. [more]

- Romanin, Samuele. Storia documentata di Venezia, 10 vols. Pietro Naratovich tipografo editore, Venezia, 1853–1864. [more] 🔗

- Vasari, Giorgio. Le vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori, e architettori. In Fiorenza, Appresso i Giunti, 1568. [more]

Related articles

- Chronology of the Fortress of Sant’Andrea

- Domenico Pizzamano

- The Fall of Venice

- A Chronology of the Fall of Venice

Leave a Reply