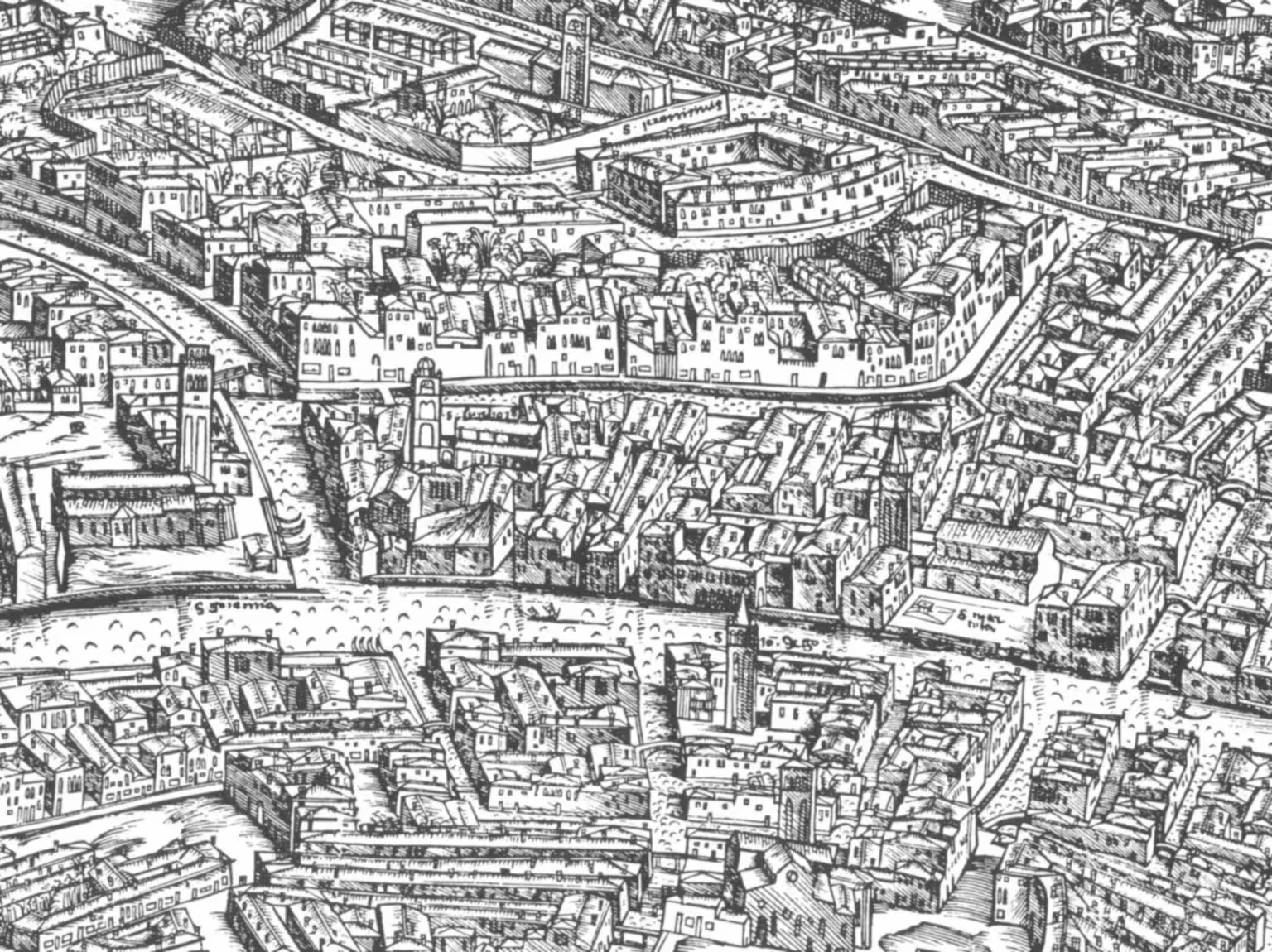

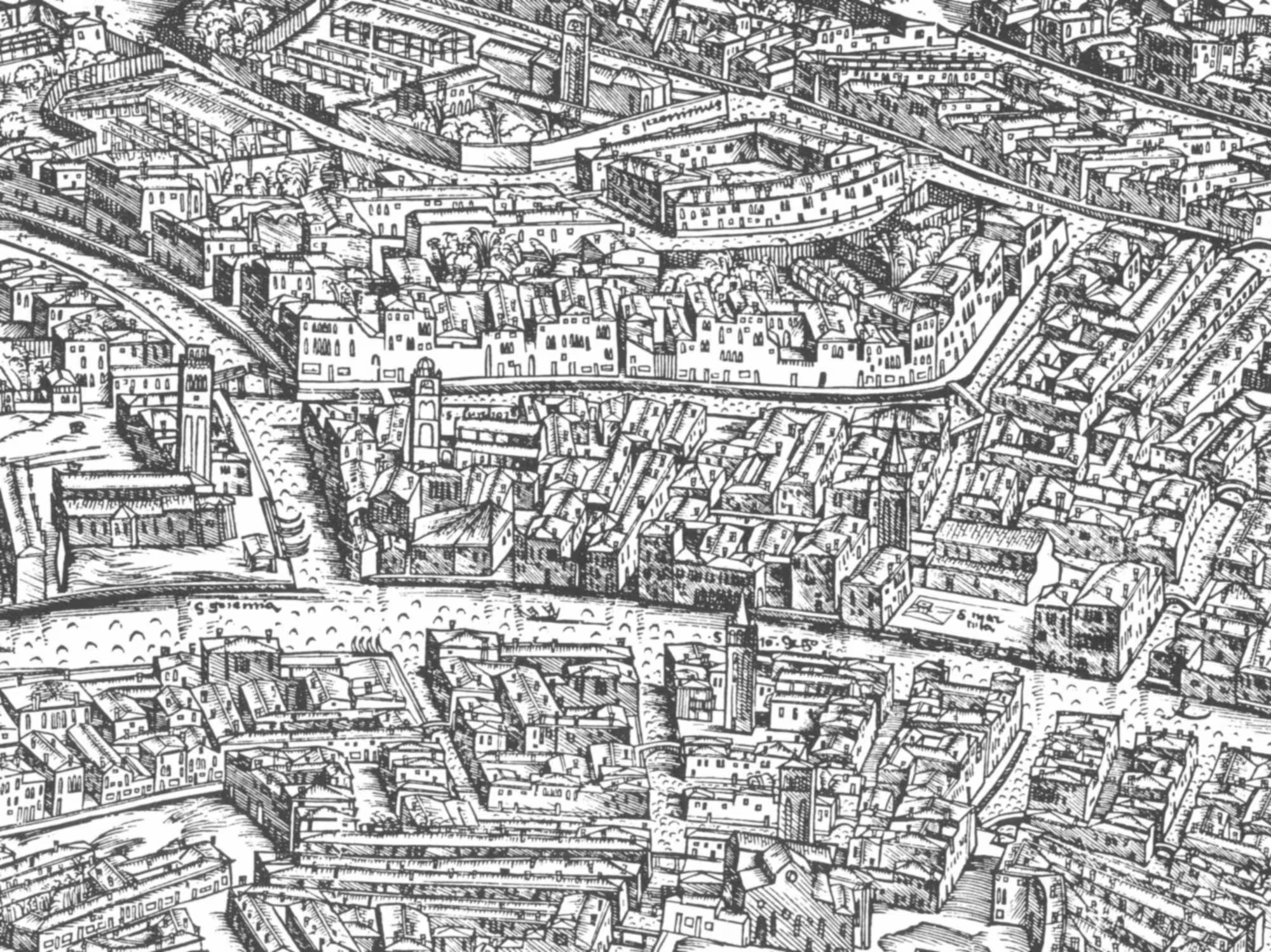

The Rio di San Leonardo was one of the most important canals of the Sestiere Cannaregio, and an integral part of the overall canal network of the city of Venice.

Strada Nova

This post is part of a series on the changes made to create the Strada Nova, which connects the railroad station with the Rialto area.

It was quite wide, so there was easy passage by boat to the many businesses in the area, and it had two ample fondamente for local pedestrian traffic.

The size and centrality of the canal meant it had a strong tidal flow, so it was quite clean according to the standards of the time.

The Rio di San Leonardo was also the only major waterway connecting the two halves of the Sestiere Cannaregio.

The connection started besides the Ponte delle Guglie on the Canale di Cannaregio, joined the Rio dei Due Ponti halfways, until it met the Rio della Misericordia.

No money

The municipal administration of Venice decided to fill in the Rio di San Leonardo in early 1818. The stated reason was that they didn’t have the money to do basic maintenance of bridges and fondamente. Filling in the canal would be cheaper.

Naturally, the residents and businesses responded to such a decision with a deluge of petitions. There was an economic side to the complaints, as many places would lose boat access to their premises. There was also a sanitary issue. Sewage usually discharged directly into the canals for the tide to clear out.

The only answer the petitioners got was that there were no money, and that they’d had to moor their boats in the nearest adjacent canals and use carts to move their goods from there.

The work of interring the canal started immediately. However, they proceeded by filling in the canal first, without making a sewer at the same time. They only built the sewer afterwards. This left the residents without a usable sewer for the entire period.

Already in July 1818, the health officers of the Sestiere Cannaregio complained to the municipal administration that the situation was untenable. They added:

We are generally surprised by the thoughtlessness of the engineers who recommend the filling in of rii and canals which the topographical nature of the City would absolutely want to be preserved, and which public health demands at all costs.

They, too, were ignored.

Why?

How come a rich city like Venice couldn’t afford basic maintenance of essential infrastructure in 1818?

Venice wasn’t a rich city any more. Those times were gone.

The Republic of Venice had maintained an aura of wealth during centuries of slow decline. This was in part because Venice had been one of the richest cities in the world, so it was a slow decline from a very high starting point. It was also because Venice had remained the Dominante, the capital of the state, all the time. Wealth always tends to gravitate towards the centre.

However, the loss of statehood in 1797 accelerated the decline. Venice ceased to be the centre, and foreign rulers therefore extracted wealth from Venice, often ruthlessly, for short-term gain.

Venice was under French revolutionary domination 1797-98, then under Austrian rule 1798-1809, followed by French imperial rule 1809-1815. With the Congress of Vienna, Venice finally passed to Austria in the periods 1815-48 and 1849-66.

The wars following the French Revolution and then the Napoleonic wars were devastating, not only for Venice. Much of Europe came shattered out of twenty-five years dominated by war and destruction. Millions died in the wars, and many more millions displaced and traumatised. The wars also destroyed innumerable businesses and trading connections.

Economically, much of Europe was in a sorry state.

At the start of 1818 Venice had been under Austrian rule for just a few years, but Austria had suffered under the wars too, so it’s not really a surprise that money was tight.

It can be argued, however, whether destroying central the physical fabric of the city to save a bit short term was the right decision.

Now?

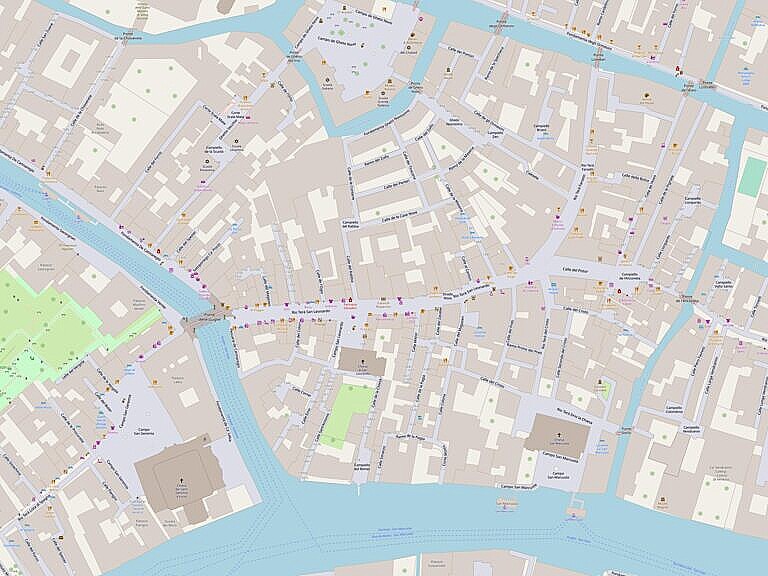

The canals interred in 1818 are still missing today. Boats with deliveries or for rubbish collection still have to do long detours, often through much smaller canals. The damage to the connectivity of the canal network is still there.

There are no obvious signs to tell that the wide roads was once a canal, except the name rio terà. There are a few less obvious signs.

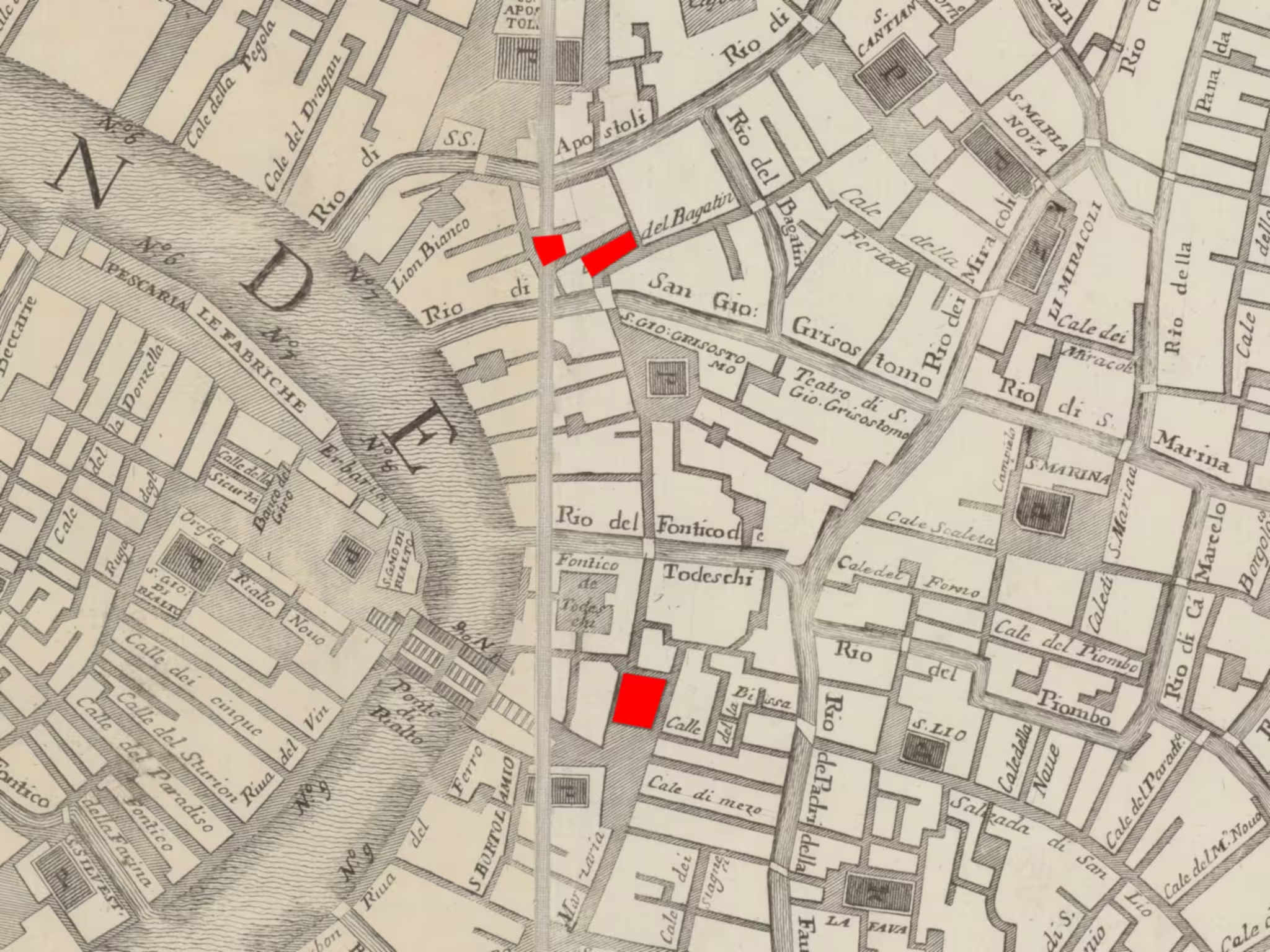

The first photo above shows how the Ponte delle Guglie arrives at the side of the Rio Terà San Leonardo. The bridge predates the interment of the canal, and originally, it landed on the Fondamenta Querini, which ran on the north side (left in the photo) of the canal.

A careful look at the pavement on the second photos reveals the separation between the Fondamenta Querini and the canal. The orientation of the slabs changes between the fondamenta and the rio terà.

The third photo shows the Campo di San Leonardo with the church building. The church was deconsecrated in 1807, and was used for coal storage in the late 1800s.

To the left of the campo was the Fondamenta San Leonardo and to the right Fondamenta Barzizza.

The names of the fondamente are forgotten now, like so much else.

Bibliography

Localities

This post is the second part of a series on the changes made to create the Strada Nova, which connects the railroad station with the Rialto area. The Strada Nova is arguably the beginning of mass tourism in Venice.

The previous post covers the Rio del Isola, and the next Due ponti e l’Anconeta.

Curiosità Veneziane by Tassini has entries on Rio Terà San Leonardo / Due Ponti (translated) and Campo San Leonardo.

Leave a Reply