The Venetian state had an ambiguous relationship with prostitution.

Prostitution was considered a necessary evil, where more harm would come from a ban than from a de facto acceptance. The greater evil was sodomy — homosexuality — which in religious terms was a mortal sin, and in Venice also a capital crime.

At least this was the general line of reasoning. However, even if a large part of the Venetian ruling elite thought prostitution morally wrong and sinful, they also profited from it, both in terms of enjoying it openly and by profiting economically.

The response of the Venetian state to the question of prostitution was therefore quite ambiguous. The authorities simultaneously banned, regulated, encouraged and organised prostitution.

The Castelletto

In 1358, the government charged the Signori di Notte (the night watchmen) and the Capisestieri (heads of the sestieri) with finding a place where the prostitutes could work without being too conspicuous.

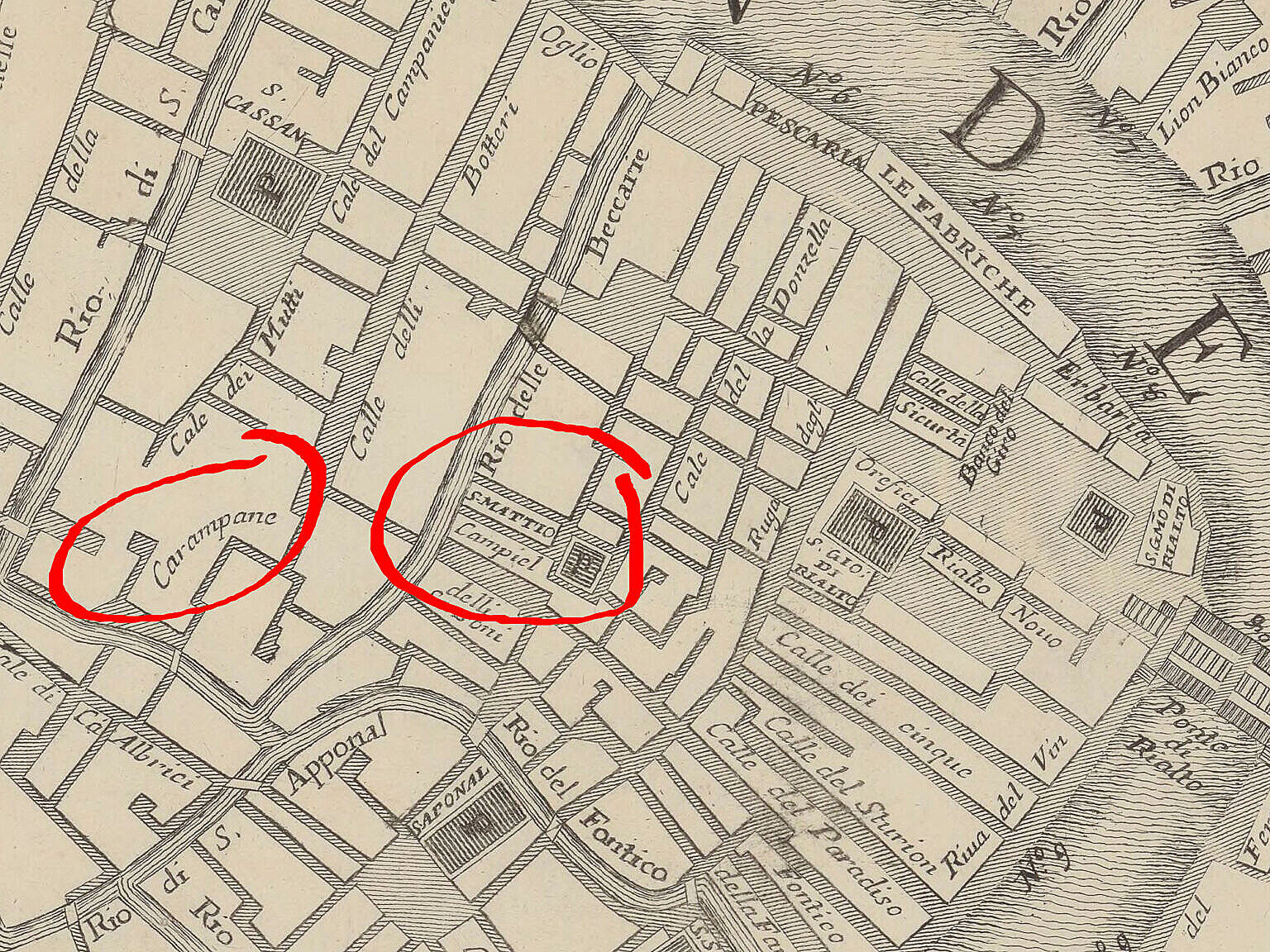

Two years later they found a group of houses in the area of the church of San Matteo (now demolished), not far from the Rialto markets, deemed suitable for the purpose.

Here the women had to live under the protection of six guardians. A matron in each house collected the earnings, and distributed them between the women at the end of the month. They all had to be in-doors in the evening at the sound of the third bell of the tower at San Marco, and they couldn’t leave the houses on the main religious feasts.

The ambiguity of the aristocracy — and therefore the state — is already evident. The state regulated the work of the women rather than outlaw it. They had protection, but they were also controlled and kept out of sight.

The Castelletto soon earned its place in Venetian popular culture. The Venetian diplomat and chronicler Giovanni Giacomo Caroldo (1480-1538), writing in the early 1500s, mentioned in the year 1372 a harlot at the Castelletto, which was a place near Rialto dedicated to sinful women.

Not everybody approved of the Castelletto, through, or wanted any association with it. In 1394, the Scuola dei Spezieri da Grosso, merchants of spices, pigments, perfumes and such, requested and obtained permission to move their guild house away from San Matteo because the area was full of prostitutes and other dishonest people.

Carampane

Over time, control slipped, and many women started working in other areas around the city. The attempt at encapsulating vice in a specific area failed, even if the Castelletto remained a centre of organised sex work for a long time.

One such well-known place of prostitution developed around the nearby Ca’ Rampani.

The Rampani family had been wealthy and influential, owning property mostly in the Sestiere San Polo, where they gave their name to both a canal and an alleyway. However, the family became extinct in 1319, and, as the last member of the family left no last will and testament, the property went to the state.

In 1421, the Ca’ Rampani became another site with legalised and regulated prostitution, like the Castelletto.

Sabellicus, who wrote the first ever ‘tourist guide’ to Venice around 1490, noted the alleyway of Carampani, from which the lupanare was recently removed.

The association between the general area, the Ca’ Rampani and legalised, regulated prostitution was such, that the word carampane became synonymous with prostitute in the Venetian language. It still is.

Laws and regulations

The economic laws of supply and demand functioned in the 1400s and 1500s too, so obviously the supply moved where there was demand, which was all over the city.

For example, in 1458 we find a law regulating where the prostitutes could work around San Samuele in the Sestiere San Marco, to get them off the main street in the area.

In 1460, another law imposed yet again that all the prostitutes lived and worked in the Castelletto at San Matteo. As always, when laws and regulations are being repeated, it is because they’re not being obeyed.

A criminal case of suspected murder by poisoning in 1477 involved a Maria Scorzupi, a prostitute living in Calle del Carbon, between the Rialto Bridge and Campo San Luca. She was imprisoned and tortured, but didn’t confess anything, so in the end she was acquitted of the suspected murder.

The Calle del Carbon was still known as a place where prostitutes lived in the 1700s.

Another law from 1489 banned prostitutes from Calle delle Rasse, near the Palazzo Ducale, and from all the inns around the Piazza San Marco. The aristocrats who owned some of these inns then complained that their businesses were losing customers. Consequently, the ban was lifted, so the women could return, and the noble landlords continue to profit from their presence.

A law from 1502 expelled all prostitutes from the Corte Contarina near San Moisè in the Sestiere San Marco.

In 1537, the Council of Ten instituted a magistracy to police matters of moral decay, called the Esecutori contro la Bestemmia — the Executors against Blasphemy. Besides blasphemy, they also regulated inns, gambling and prostitution, and prosecuted crimes against virgins, of profanation, and any other matter of public decorum.

Social control

The prostitutes in Venice, both accepted and not accepted by society, lived under many restrictions. However, as is evident from the repetitious laws and regulations, often the enforcement of the rules failed.

Already in 1438 the Consiglio Maggiore decreed that officials at Rialto like at San Marco cannot receive presents of roses, flowers or indeed any other things or any other gifts from said prostitutes, or from others in their name … that on the day of Christmas that public house shall be closed, like on the Eve of Christmas, and similarly for Easter.

A decree from 1644 recapitulates many of these restrictions on the daily lives of prostitutes.

Prostitutes could not live in a house on the Canal Grande, nor could they live in houses costing more than a hundred ducats in rent.

They were unable to go down the Canal Grande at the time of the corso. Most Italian cities have a Corso in the city centre, where ‘respectable’ families went for a daily stroll, to see and be seen. In Venice, the Corso was the Grand Canal, and the stroll happened in a boat.

Wandering the city in two-oared boats was also illegal for prostitutes, probably to prevent them from appearing too glamorous or wealthy.

Prostitutes could not enter the churches on the occasions of festivities, absolutions or any other activities of devotion.

Any kind of ostentation was banned, as was dressing in a way so they could be mistaken for ‘innocent’ women. They weren’t allowed to wear white as young unmarried women of good family did, and they couldn’t wear gold, jewels or pearls (genuine or false).

They were also excluded from giving testimony in criminal trials, and if their clients didn’t pay for the services, the sex workers couldn’t take the claim to court.

Courtesans and harlots

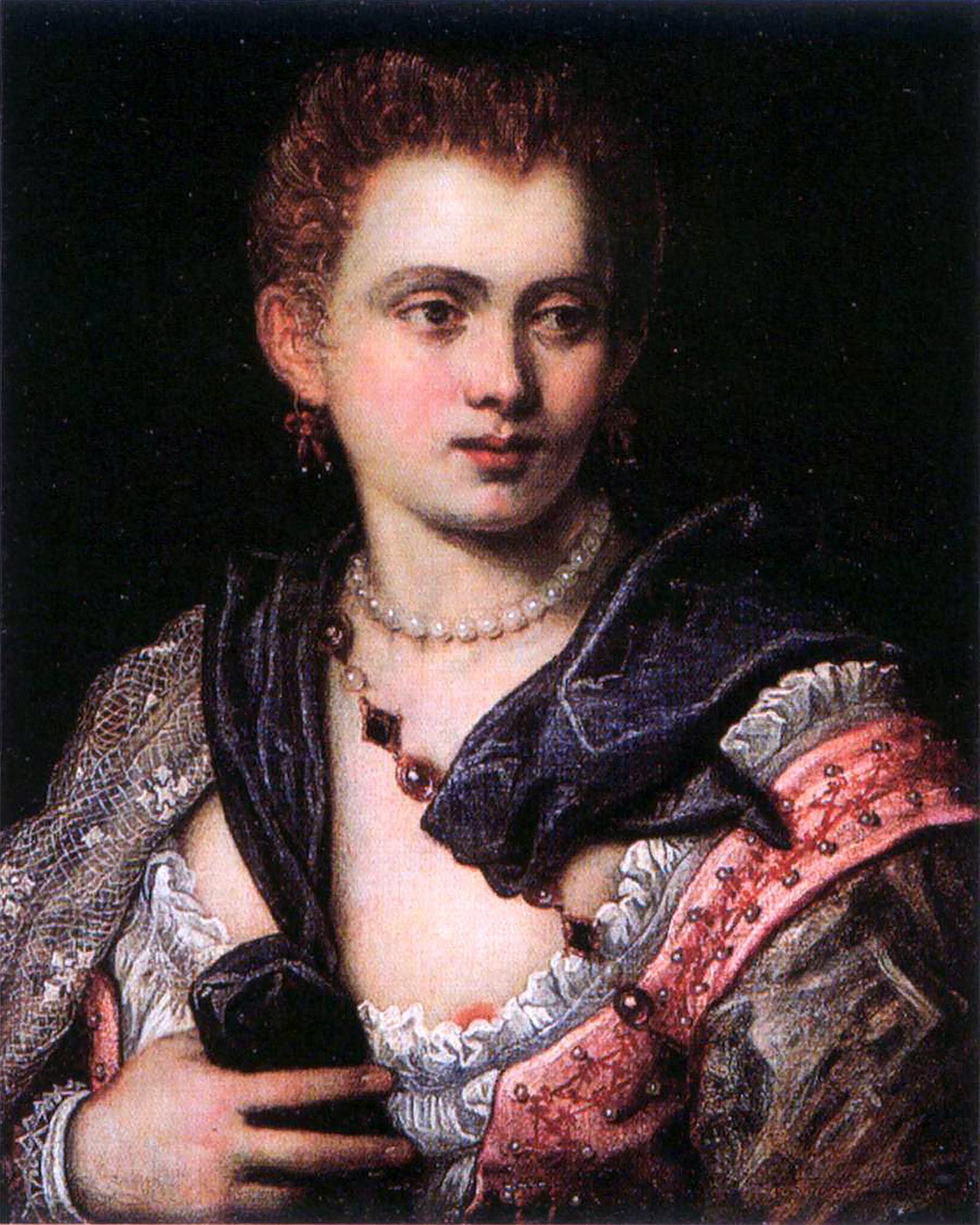

That such rules were considered necessary tells us that some courtesans had enough money to wear silk and pearls while being rowed around the city in luxurious boats. In short, they had enough money to look like they were upper class, which the ‘real’ upper class obviously couldn’t accept, hence the restrictions.

The ambiguity — or bigotry — is evident.

Venice was a class society with huge differences between the rich and poor. There were few possibilities for upwards social mobility, and for young women from a poor background there were almost none, if not prostitution.

While most prostitutes remained poor, as meretrici or cortigiana di lume, others managed to obtain fame and wealth, in good part because they came from the right class of citizens. They were the cortigiane oneste — the honest courtesans — of whom there was a public catalogue.

The Catalogo di tutte le Principal e più Honorate Cortigiane di Venetia from the late 1500s listed them by name, address, who was their go-between, and by their prices.

Angela Zaffetta

One of the most famous of these cortigiane honeste in the 1500s was Angela dal Moro, known as Zaffetta. She was born in humble circumstances, but she became economically independent and maintained her family later in life. Her father (or stepfather) was Borrin, a zaffo, which means a guard or a watchman, hence the name Zaffetta.

Not unexpectedly, her life was full of scandals, as she became almost an institution in high society. A nobleman, Lorenzo Venier, who clearly didn’t approve of her, even wrote a very long poem about the gang-rape of Zaffetta by thirty-one men after she had rejected the approaches of a nobleman.

Here is one verse, following one about hideous courtesans:

Fra queste poche ce n’è una sola

Che tiensi prima in la fottuta setta.

Non è la Griffa, non è la Bigola,

Che le parole profuma e belletta.

Aiutatemi à scioglier la parola;

La sua altezza ha nome la Zaffetta,

Che si tien nata di sangue reale,

Poi che patrigno l’è Borrin bestiale.

Among these few there is only one

Who considers herself first in the cursed sect.

It is not Griffa, it is not Bigola,

that words perfume and embellish.

Help me unravel the word;

Her highness is named Zaffetta,

Who considers herself of royal blood,

But what a bestial stepfather Borrin is.

Zaffetta was probably the model for the painting Venere di Urbino by Titian. She and Titian knew each other well, and they might have had an affair.

Veronica Franco

Another cortegiana honesta, Veronica Franco (1553-1591), was also a poet and an intellectual. According to the catalogue she worked around Santa Maria Formosa, with her mother, also a courtesan in the catalogue, as her go-between.

She lived at San Moisè at the time of her untimely death at the age of forty-six. While her economic situation wasn’t good in her later years, she still set money aside in her testament for the less fortunate:

To two young women of good family for their marriage, but if there are two prostitutes who would want to leave the bad path and marry, or become nuns, in that case the said two prostitutes should be favoured, and not the young women.

The fear of sodomy

The stated reason for the de facto acceptance of prostitution was sodomy — homosexuality.

The idea was that if men didn’t have a ‘natural’ outlet for their sexual needs, they would find an ‘unnatural’ one in homosexuality.

Venice was, and had always been, a sea-faring nation, both for war and for commerce. Long journeys by sailed or rowed ships take a long time, and there are usually only men on board. Taking that into account, it would be naive to believe the Venetians didn’t have some very solid experiences with sodomy.

Yet, it was judged very harshly.

The Council of Ten decreed in the 1400s that to fight the abominable vice of sodomy, two noblemen be elected in each parish, who would meet each week to monitor the situation, and that all doctors and barbers approached for ailments in the posterior parts attributable to sodomy were obliged to report it within three days.

The punishment for sodomy was death by hanging between the two columns in Piazza San Marco. Afterwards, the body was burned until only ashes remained.

While prostitution was still considered immoral, it was not a mortal sin or a capital offence.

The Ponte de le Tette (literally the Bridge of Tits) and the adjacent Fondamenta de le Tette and Calle de le Tette, all near the Ca’ Rampani, have their name from the habit, sanctioned by the authorities, of female prostitutes sitting in the windows with their breasts exposed, so prospective clients could be assured that they offered only safe vice.

Just like with wine, prostitution has also left its mark on Venetian topography.

Related articles

- State institutions of the Republic of Venice

- A Venetian Law

- A catalogue of Venetian prostitutes

- An earl, a girl and a gondola

- Venice rhymes with Wine

- Streets in Venice

Translated sources

- Catalogue of all the principal and most honoured Courtesans of Venice (translated)

- Catalogo di tutte le principal et più honorate Cortigiane di Venetia (original)

- Carampane — Curiosità Veneziane

- Carampane — Lessico Veneto

- Carampane — Dizionario

- Meretrici — Lessico Veneto

- Esecutori contro la Bestemmia — Lessico Veneto

- Magistrato de la Biastema — Dizionario

- Barbo — Curiosità Veneziane

- Paglia — Curiosità Veneziane

Bibliography

- Boerio, Giuseppe. Dizionario del dialetto veneziano. Venezia : coi tipi di Andrea Santini e figlio, 1829. [more] 🔗

- Leggi e memorie venete sulla prostituzione fino alla caduta della Republica, a spese del conte di Oxford, 1870-72. Venezia, Tipografia del Commercio di Marco Visentini, 1872. [more] 🔗

- Mutinelli, Fabio. Lessico veneto che contiene l'antica fraseologia volgare e forense … / compilato per agevolare la lettura della storia dell'antica Repubblica veneta e lo studio de'documenti a lei relativi. Venezia : co' tipi di Giambatista Andreola, 1851. [more] 🔗

- Sabellico, Marco Antonio and Maurizio Vittoria (ed.). Del sito di Vinegia : la più antica guida di Venezia, orig. pub. 1502. Venezia : Venipedia, 2017.

- Tassini, Giuseppe. Curiosità Veneziane ovvero Origini delle denominazioni stradali di Venezia. 1863. [more] 🔗

- Tassini, Giuseppe. Veronica Franco celebre poetessa e cortigiana del secolo 16. Edited by Giuseppe Tassini, 1888. [more]

Leave a Reply