On the Grand Canal there’s a particularly crooked house. Even if it isn’t as large and imposing as many other palaces, it is quite noticeable. It is the Ca’ Dario from the late 1400s.

The façade is adorned by an inscription: Genio Urbis Joannes Darius.

Giovanni Dario

The inscription on the façade refers to Giovanni Dario (1405-1487).

Despite the beauty and location of the palace, the Dario family was not noble. They were cittadini, citizens, therefore middle class, rather than nobil uomini, noblemen, i.e., aristocracy.

This was hugely important in ancient Venice because it decided which positions in the government of the state a person could aspire to.

Only noblemen had any kind of political say. The Consiglio Maggiore was the highest authority of the Venetian state. It was exclusively made up of the adult men of the aristocratic families of Venice. Middle-class citizens were excluded.

Giovanni Dario rose to the highest ranks allowed by his birth. Within the political and administrative system of Venice, that meant secretarial positions to the highest organs of the state. In the 1470s he was, as Secretario del Senato, Secretary to the Senate.

He was also a learned man, who spoke Greek. This led to an assignment to Constantinople, as deputy to the Bailo, the ambassador of the Republic of Venice to the Ottoman court.

In this role, Giovanni Dario was central in the conclusion of a peace treaty between the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Turkish Empire in 1479. Besides the honorary title of Salvatore della Patria — Saviour of the Fatherland — he also received an estate in Noventa, near Padova, and a large sum of money from Venice, and three robes of golden fabric from the Sultan.

At least part of the money went into the palace.

The Ca’ Dario palace

Giovanni Dario commissioned Pietro Lombardo to either build or refurbish the palace, as part of his daughter’s dowry.

The Ca’ Dario is a classic, and much admired, example of early Venetian Renaissance. It is most likely built in the late 1480s. It is therefore contemporary with the Scuola Grandi di San Marco and the Madonna dei Miracoli church.

At his death, in 1494 at the age of eighty, the property passed to Marietta Dario, the oldest daughter of Giovanni Dario.

She had married Vincenzo Barbaro from the wealthy and noble Barbaro family, which lived in the next door palace, Ca’ Barbaro-Wolkoff. The little square behind the Ca’ Dario is the Campiello Barbaro, the alleyway Ramo Barbaro.

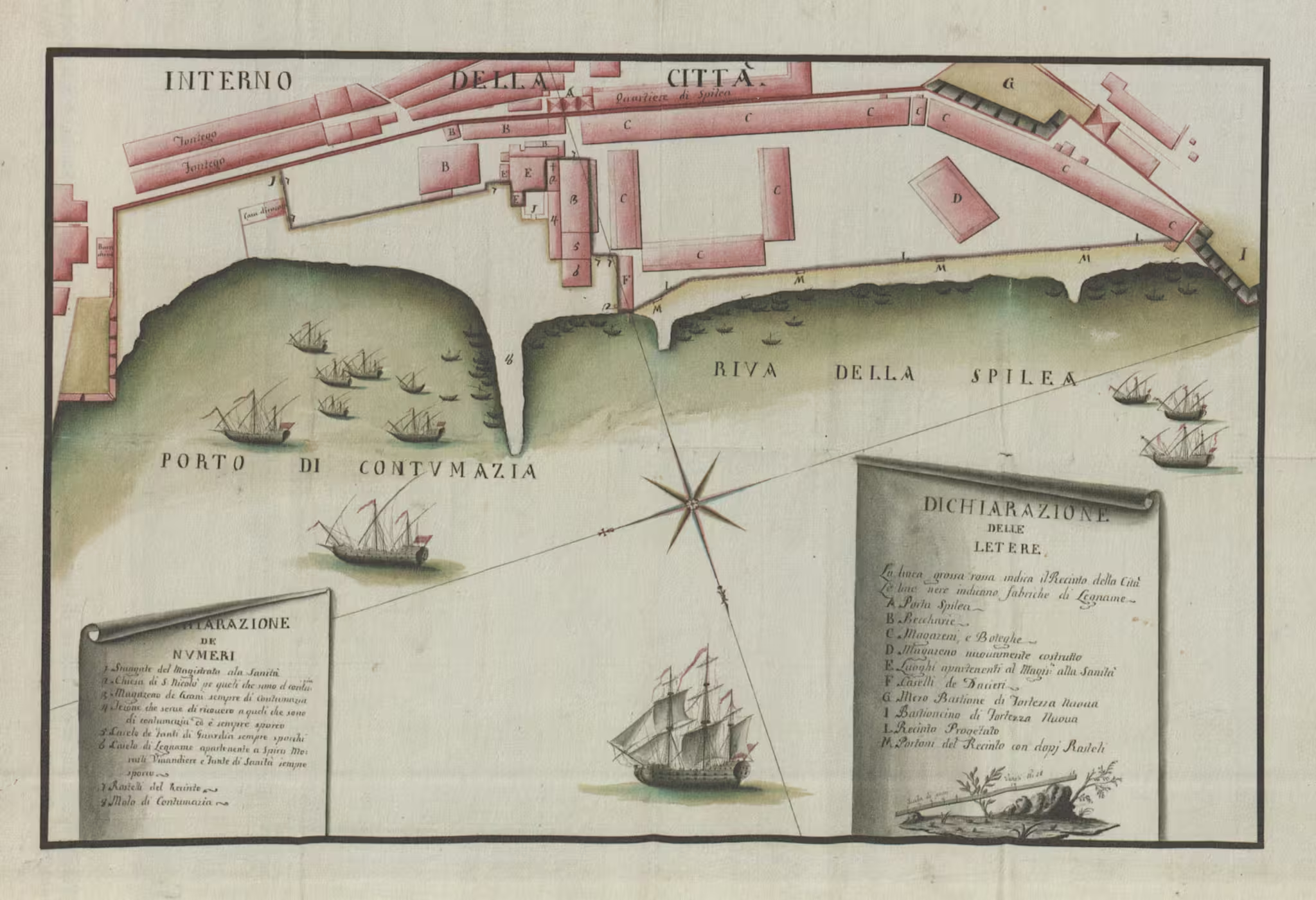

In the early 1500s, under the ownership of Marietta and her three sons, the Venetian Republic rented Ca’ Dario. It subsequently served as the embassy of the Ottoman Empire to Venice, which will no doubt have been quite profitable for the owners.

The Barbaro family owned the Ca’ Dario until the late 1700s, around the time of the fall of the Republic, when they sold it to a wealthy Armenian diamond merchant.

In the last few centuries, the palace has changed hands many times.

Dating of the Ca’ Dario

John Ruskin, in his The Stones of Venice, cites his friend Rowdon Brown, who owned the palace 1837-42, as to the dating:

Fontana dates it from about the year 1450, and considers it the earliest specimen of the architecture founded by Pietro Lombardo, and followed by his sons, Tullio and Antonio. In a Sanuto autograph miscellany, purchased by me long ago, and which I gave to St. Mark’s Library, are two letters from Giovanni Dario, dated 10th and 11th July 1485, in the neighbourhood of Adrianople; where the Turkish camp found itself, and Bajazet II. received presents from the Soldan of Egypt, from the Schah of the Indies (query Grand Mogul), and from the King of Hungary: of these matters, Dario’s letters give many curious details. Then, in the printed Malipiero Annals, page 136 (which err, I think, by a year), the Secretary Dario’s negotiations at the Porte are alluded to; and in date of 1484 he is stated to have returned to Venice, having quarrelled with the Venetian bailiff at Constantinople: the annalist adds, that ‘Giovanni Dario was a native of Candia, and that the Republic was so well satisfied with him for having concluded peace with Bajazet, that he received, as a gift from his country, an estate at Noventa, in the Paduan territory, worth 1500 ducats, and 600 ducats in cash for the dower of one of his daughters.’ These largesses probably enabled him to build his house about the year 1486, and are doubtless hinted at in the inscription, which I restored A.D. 1837; it had no date, and ran thus, URBIS . GENIO . JOANNES . DARIVS. In the Venetian history of Paolo Morosini, page 594, it is also mentioned, that Giovanni Dario was, moreover, the Secretary who concluded the peace between Mahomet, the conqueror of Constantinople, and Venice, A.D. 1478; but, unless he build his house by proxy, that date has nothing to do with it; and in my mind, the fact of the present, and the inscription, warrant one’s dating it 1486, and not 1450.

Ruskin, John. The Stones of Venice, 3 vols. 1851–53, vol. III.

Curses, suicides, murders …

Factual history won’t sell any newspapers or go viral online, so somebody decided they could do better. In fact, the stories of curses, and all the owners committing suicide or meeting an untimely, violent death, only start in the 1990s.

At that time, a high-flying Italian business tycoon, Raul Gardini, owned the palace. However, he got entangled in allegations of corruption, and in 1993 he committed suicide. Not in Venice or anywhere near the Ca’ Dario, but in his home in Milan.

This event opened the floodgates of evidence-less imagination.

Suddenly, Giovanni Dario had died in disgrace and misery, and his daughter committed suicide in the palace. Of course, nothing of the kind every happened.

Giovanni Dario died at eighty, a very wealthy and highly esteemed man, and his daughter married into a wealthy family, had her own wealth, and was host to the embassy of the Ottoman Empire. Her three sons lived long and prosperous lives.

The above-mentioned Rawdon Brown, who owned the palace for some years, was supposed to have committed suicide, except he died an old man in 1883.

The Venetian archaeologist, historian and author Davide Busato has published a long article countering most of these rather absurd claims (in Italian).

Ca’ Dario today?

Apparently the palace is up for sale again, for the modest ask of almost $20 million.

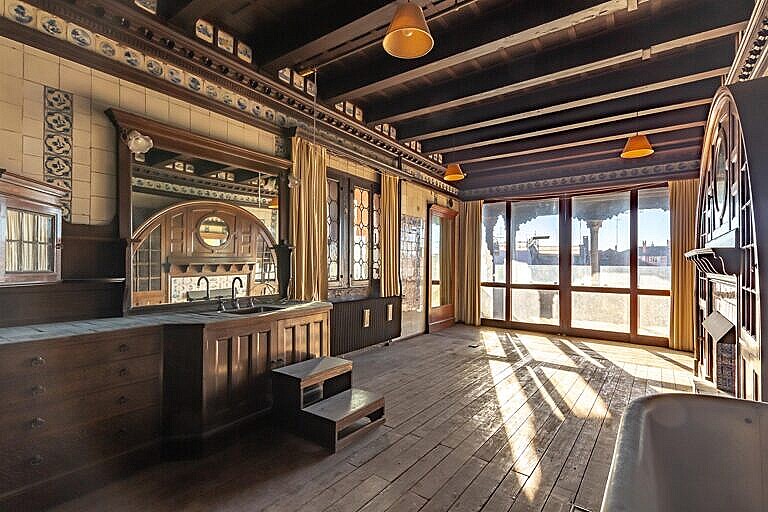

I’ve taken the liberty of copying some of the photos from the FT Property listings site, to give an idea of how the Ca’ Dario is inside today. The meta-data didn’t contain any credits or copyright notices, so I don’t know who has the rights to the photos.

Bibliography

Ruskin, John. The Stones of Venice, 3 vols. 1851–53.

Tassini, Giuseppe. Curiosità Veneziane ovvero Origini delle denominazioni stradali di Venezia. 1863.

Leave a Reply