On the 19th of March, 1474, the Pregadi (the Senate of the Republic of Venice) enacted a law instituting an organised patent system.

This is the first time intellectual property appears in the legal system of an European state.

The basics of a patent system was already there, 550 years ago. An invention must be new, useful and actually work:

… who invents in this city any new or ingenious contraption non already invented under our rule, if he makes it to perfection so it can work and function …

The inventor must register the invention to get the patent protection:

… are obliged to give notice hereof to the office of our provveditori de comun …

The provveditori di comùn were Venetian magistrates in charge of, among other things, regulating trade.

The reward for the inventor was ten years of patent protection:

It is prohibited for anybody in any land or place of ours, making any other similar contraption, and those must obtain the consent and license of the author for ten years.

Faced with a patent infringement, the inventor can take the offender to court:

… they are free to denounce it to any tribunal in this city …

and

If the tribunal says he has counterfeited, he is forced to pay hundred ducats and the aforementioned contraption shall be destroyed.

This Venetian patent law from 1474 is all in all a surprisingly modern piece of legislation.

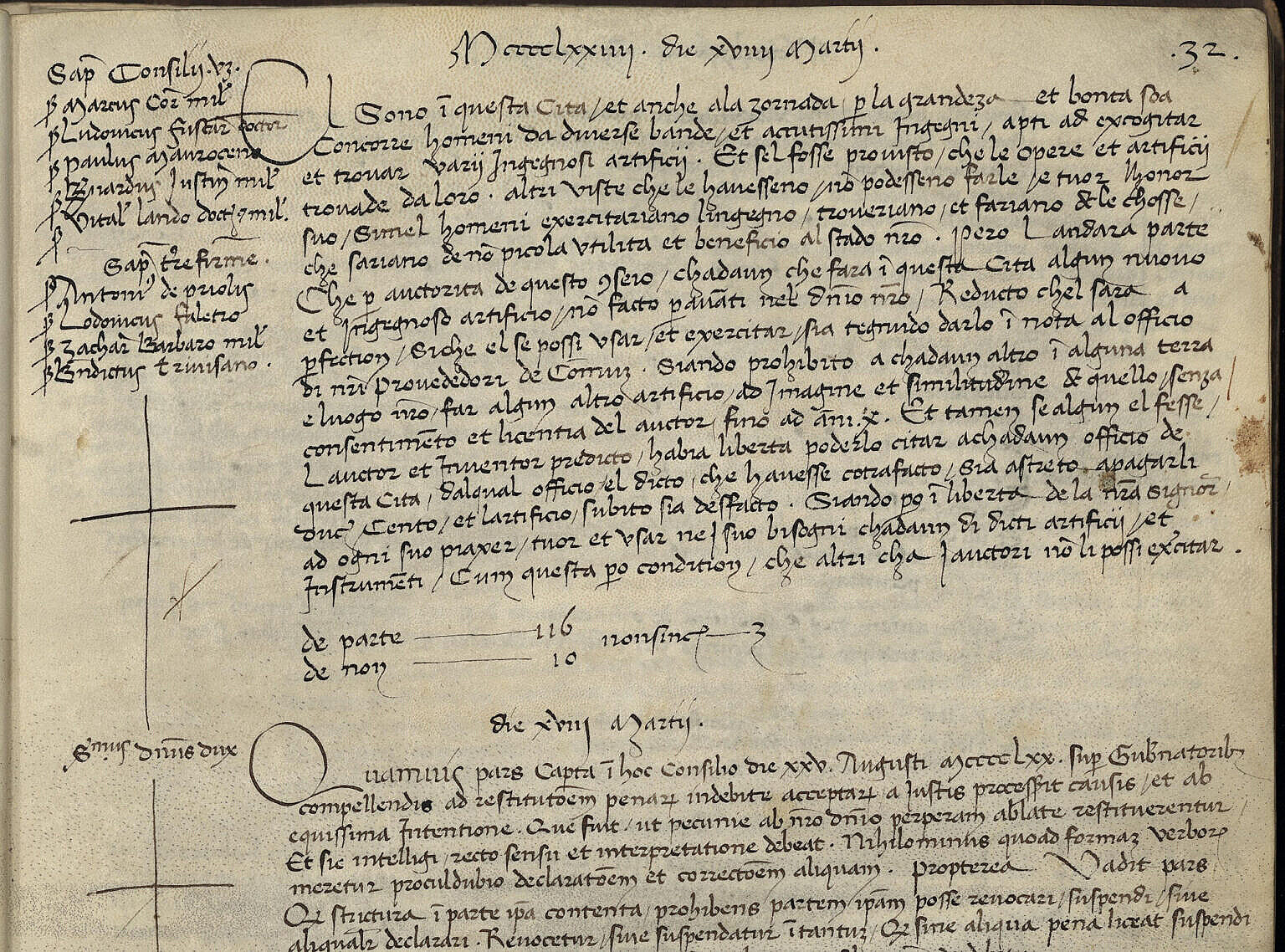

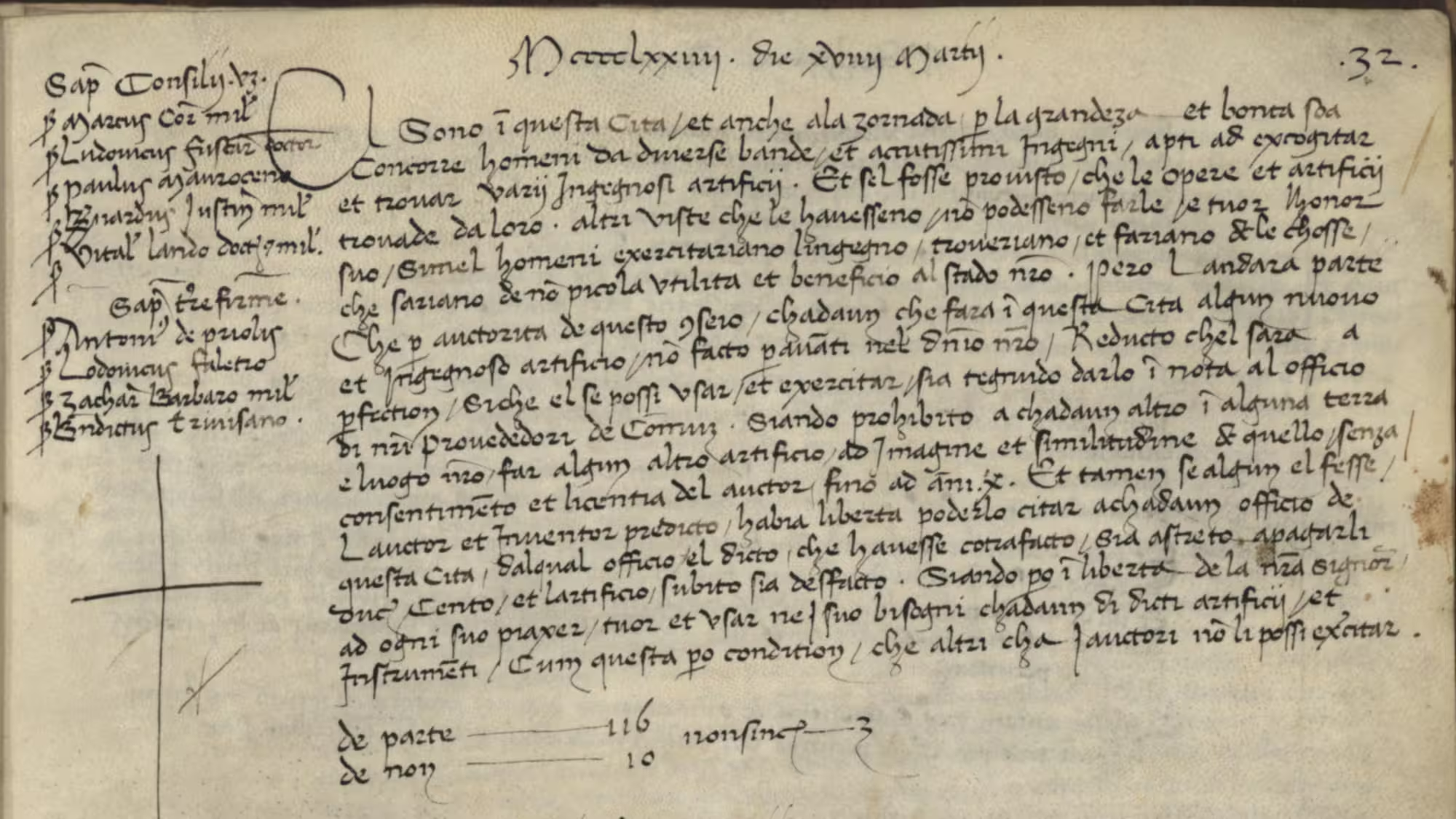

A piece of parchment

The secretaries of the Venetian Senate copied down all deliberations on parchment. The sheets of parchment were later bound into books, and over time found their way into the Archivio di Stato di Venezia — the Italian State Archives in Venice. They have digitised many of the treasures, including this book.

The law looks like this (image 64 when following the link).

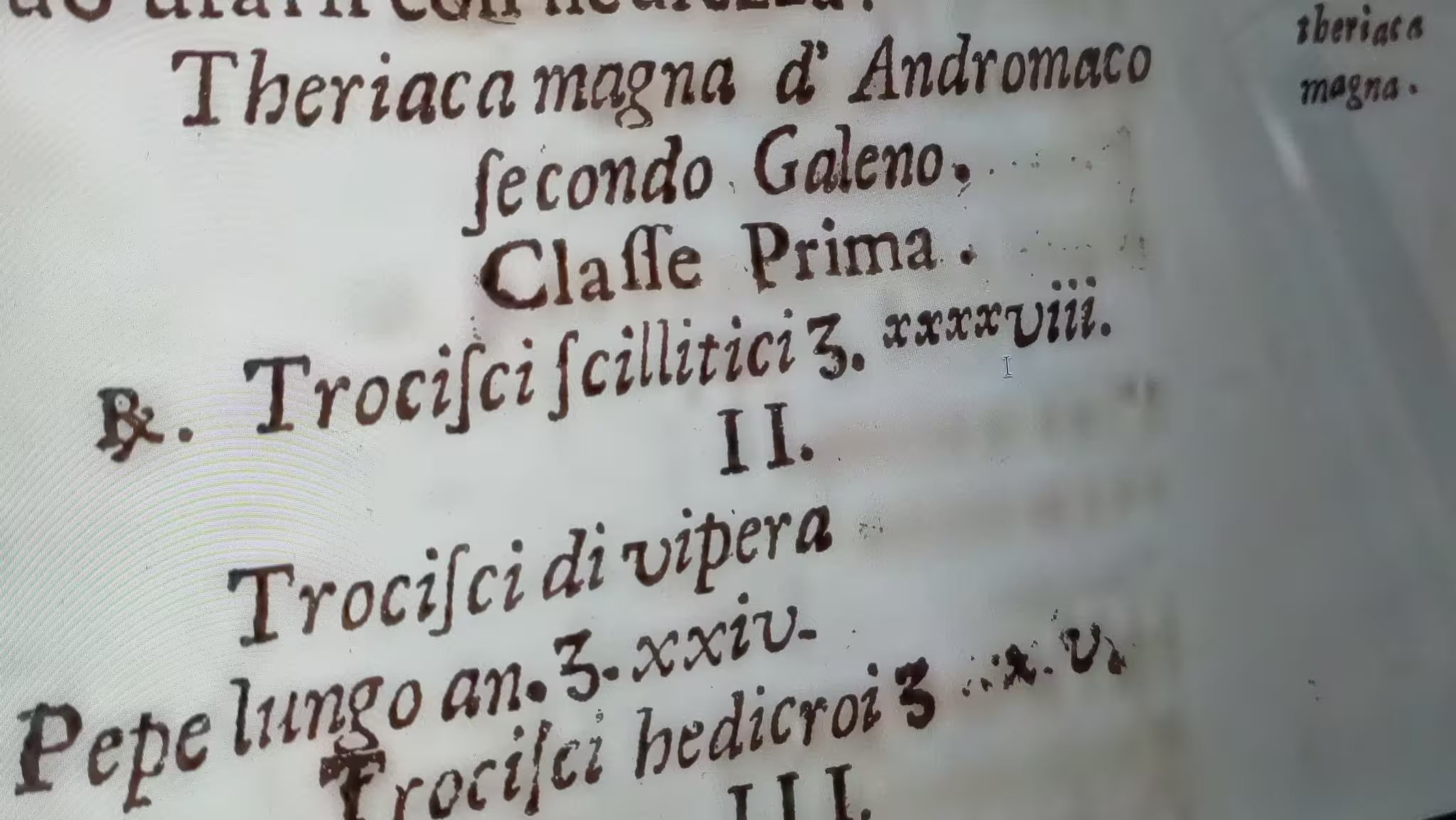

This text is in Venetian, while the following deliberation of the Senate, further down the same page, is in Latin.

Transcription

MCCCCLXXIIII Die XVIIII Martii

El sono in questa cita / et anche ala ziornada per la grandeza et bonta sua

concorre homini da diverse bande et accutissimi ingegni / apti ad excogitar

et trovar varii ingenosi artificii. Et se el fosse previsto che le opere et artificii

trovade da loro – altri viste che le havessero no potessero farle ne tuor honor

suo / Simil homeni exercitaziano l’ingegno / troveziano / e fazzano e le stesse

che faziano de no picola utilta e beneficio al stado nostro. Però l’anderà parte

che per auctorita de questo ufizo / cadaun che faza in questa cita alcun nuovo

et ingegnoso artificio non facto par avanti nel Dominio nostro / Reducto chel fara a

perfection / sichè el se possi usar / et exercitar sia tegnudo darlo in nota al officio

di nostri provededori de comun – Stando prohibito a chadaun altro in alcuna terra

e luogo nostro far algun altro artifizio ad imagine e similitudine et quello tenga

consentimento e licentia del auctor sino ad anni X. Et tamen se alcun el fesse

l’auctor et inventor prodicto / habra libera poderlo citar achadaun officio de

questa cita / Dalqual officio el dicto che havesse cotrafacto sia astreto apagarli

duc centro / et l’artificio sudito sia destructo. Stando poi in liberta de la nostra signora

ad ogni suo piaxer / tuor et usar nei suo bisogni chadaun di dicti artificii et

instrumenti / Cum questa po condition / che altri cha l’auctori no li possi excitar.de parte …. 116

de non … 10non sinc … 3

Translation

There are in this city, and every day due to its greatness and goodness men arrive from various places, with acute inventiveness, apt at inventing and creating various ingenious contraptions. And if it was thus that the works and contraptions invented by them – when others see them, they can not make them, nor take merit for them. Such men exercise their inventiveness, and invent and create, the things they make are of no small utility and benefit for our state. Therefore, let it be decided that by the authority of this office, that who invents in this city any new or ingenious contraption non already invented under our rule, if he makes it to perfection so it can work and function, are obliged to give notice hereof to the office of our provveditori de comun. It is prohibited for anybody in any land or place of ours, making any other similar contraption, and those must obtain the consent and license of the author for ten years. Likewise if anybody is author or inventor as above they are free to denounce it to any tribunal in this city. If the tribunal says he has counterfeited, he is forced to pay hundred ducats and the aforementioned contraption shall be destroyed. Our signoria shall be at liberty to take and use at leisure any of said contraptions and instruments for its needs, under the condition that no others than the inventor can operate them.

Votes in favour: 116

Votes against: 10Not sincere: 3

I have kept this translation as close to the original as possible.

There are several other translations available, for example on Wikipedia and on the site Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900).

Related articles

- A Venetian Law

- Però l’anderà parte — vadit pars

- State institutions of the Republic of Venice

- Monachini, Moneghini — Lessico Veneto

Leave a Reply