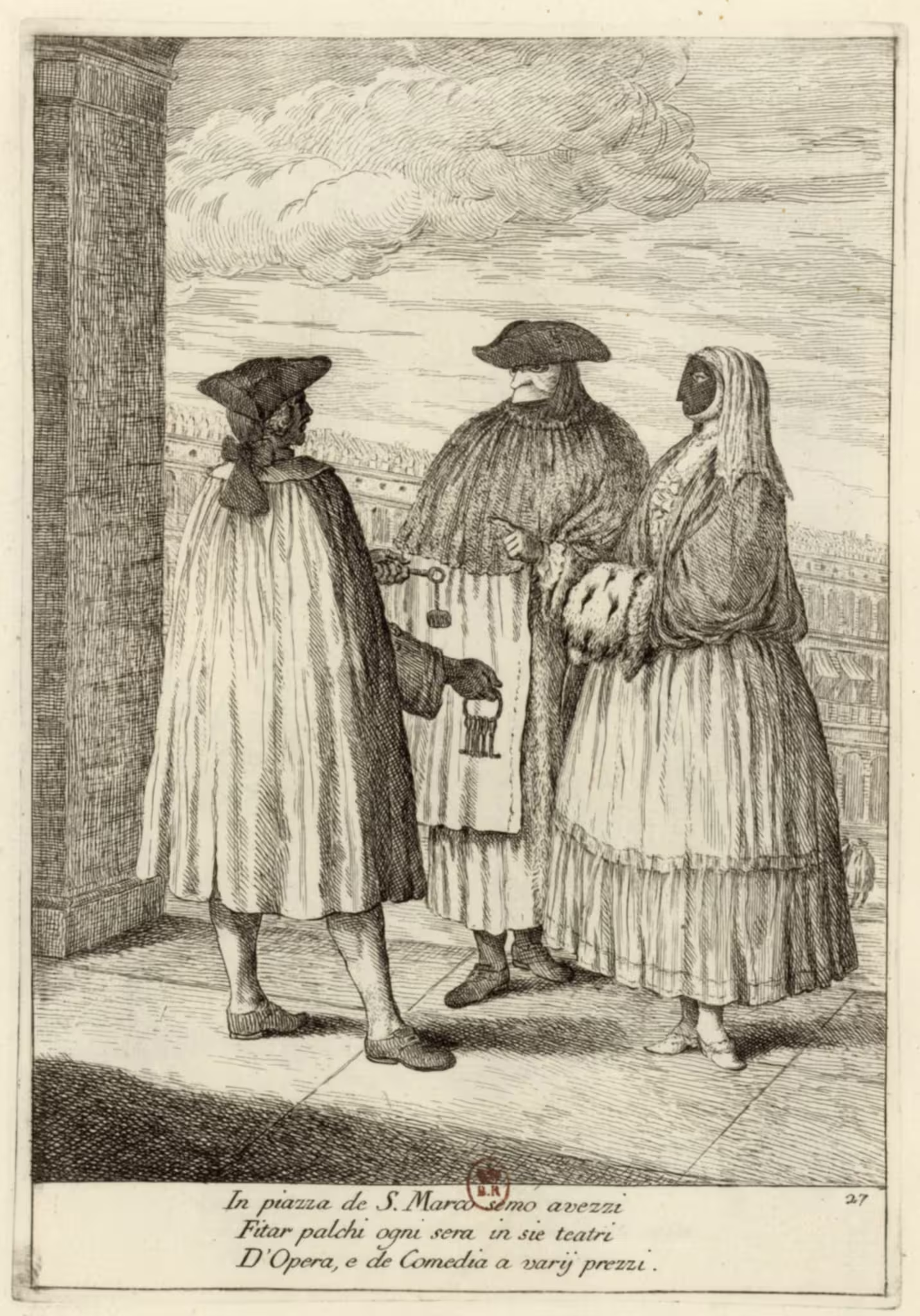

On February 2nd the Doge walked down to the church of Santa Maria Formosa, where the gastaldo of the cassellari — the leader of the box-makers’ guild — gifted him two oranges and two straw hats before they entered the church together for mass.

Venetian Stories

This post is an issue of our newsletter — Venetian Stories — which goes out every few weeks, to keep in touch and share stories and titbits from and about Venice and its history.

The Venetians did this every year for over eight centuries. The tradition started sometimes in the mid-900s and lasted the end of the Republic of Venice in 1797.

Heroic carpenters

The box-makers were a specialised branch of carpenters. They made boxes of all kinds, from simple storage boxes for goods to elaborate boxes for the dowry of brides from wealthy families.

The latter boxes with inlays of tropical hardwood and mother of pearl, or painted in different ways, were important status symbols and often kept in families for generations.

The statute of the guild — the mariegola of 1449 — explains the reason for the Doge’s annual visit to their church in the in this way:

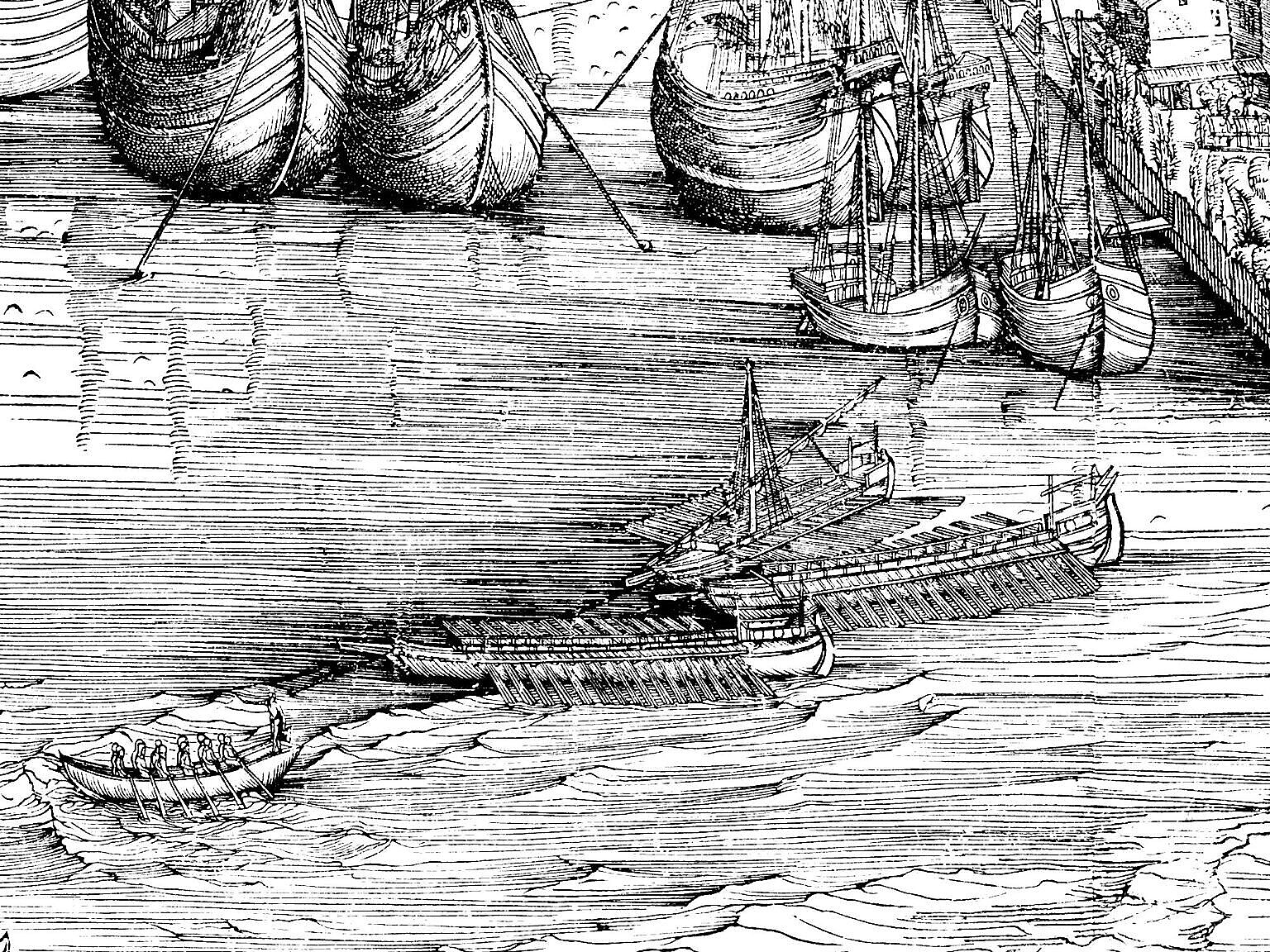

And the box makers from the area of S. Maria Formosa were ready, and in good order, making shields of the planks with which they made the boxes, and everybody embarked on the galley, and they rammed it, and the box makers were the first to board the galley, and many died on both sides, and they cut the Triestini in pieces, not taking anybody their prisoner. And this turned the Doge thus that they shouldn’t be buried on land, but that the sea would be their tomb due to the great injustice and offence they had done the Venetian.

Giuseppe Tassini: Curiosità Veneziane, entry Casselleria.

Pirates and maids

The events recalled in the mariegola of the box-makers’ guild happened half a millennium earlier.

In the earliest times the Venetians did weddings once a year, on the last day of January. It was a communal event, basically a mass wedding, presided by the bishop.

Sometimes in the mid-900s, on January 31st, all the brides gathered in the church of San Pietro di Castello. Each with her the box for their dowry.

As the girls were waiting for their grooms to arrive, pirates suddenly entered the church. They grabbed girls and dowries alike, and scampered with their booty in the galleys towards the sea. Some sources name the assailants as from Trieste, others from Istria or from the Naretva region.

The alarm — all’arme means ‘to arms’ — went out through the city and the Venetians set after the pirates as fast as they could. They caught up with them the day after, some 50-60 km to the north, not far from Caorle. The pirates had stopped to divide the spoils.

A fierce battle ensued, in which the Venetians killed all the pirates, giving no quarter.

Having recovered the girls and their dowries, the small fleet returned to Venice. The wedding was held the day after, on February 2nd.

These events were subsequently celebrated until 1378 as the Festa delle Marie.

The reward

The box-makers had done their part, and more so. The Doge therefore approached the gastaldo of the guild on their return to Venice, complemented them on their performance and offered them a reward.

To his surprise the request was not for gold or privileges. The gastaldo simply asked that the Doge would come and hear mass with them once a year, on that same day, February 2nd.

The day was the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The church of Santa Maria Formosa was at that time the only church in Venice dedicated to the Madonna, so the request made some sense.

Wanting to give the gastaldo time to elaborate, or add something more substantial to his request, the Doge agreed, but jokingly asked “But if it rains?” The box-maker simply replied: “We will give you cover.” The Doge persisted: “And if I’m thirsty?” “We will offer you food and drink,” replied the gastaldo.

Not getting anywhere, the Doge agreed.

Straw hats, oranges and malvasia

This deal was kept by all the Doges until the end of the Republic of Venice.

On the morning of February 2nd, the Doge walked the short way from the Palazzo Ducale to the church of Santa Maria Formosa.

The pievan — the parish priest — had extended a white cloth on the bridge in front of the church, and the Doge had to give an offer to the church to pass. The coin was a small copper coin called a bianca — white. The Venetian mint — la zecca — minted these coins specially for just this one ceremony.

Once across the bridge the Doge met the gastaldo of the box-makers’ guild, who offered him two oranges and two straw hats to make good on the ancient promise.

Later they added two bottles of malvasia and they gilt the straw hats.

Malvasia is a Greek wine which was very popular in Venice. The word still appears in many place names in Venice

Access to power

The request of the gastaldo of the box-makers was not as silly as it might seem.

Access to power is power.

Early Venetian society was, like most other medieval societies, a very unequal society.

The wealthiest elite monopolised political power, and only the men from richest families had a vote in public affairs — the res publica. In the early period this group was rather fluid, but they were richer than any box-maker was ever likely to get.

If you’re not part of the ‘public’ of the res publica, your best chance of getting heard is through somebody who is.

The request of the box-makers was therefore quite savvy. They didn’t ask for money or privileges, they asked for access. That way, if in the future they had a grievance of some kind, they knew they would have the ear of the head of state within a year.

If you have very little in terms of political clout, that is something.

Social cohesion

Why did the Doges and the aristocracy keep up the tradition? What was in it for them?

Like with the associated Festa delle Marie, the wealthy elite could have discontinued the tradition if it was no longer convenient.

They didn’t. They didn’t end the visits because they still served a purpose.

The purpose was that of maintaining social cohesion and allegiance to the state.

Societies with a high level of inequality easily build up social tensions, which can become social conflict if not alleviated somehow. The Romans had bread and circuses, and the Venetians had feasts, celebrations and competitions that involved the lower classes, exactly for this reason.

Sometimes, like with the Festa delle Marie, the safety valve let out too much steam. The event became too rowdy and risked getting out of control, so the tradition ended.

Having an ancient guilt of respectable artisans present the Doge with symbolic gifts, on the other hand, was rather innocuous. The guilt showed their allegiance to the state, even if they didn’t have a direct say in government matters. Such bonds were important to keep society together, in spite of the built-in differences between the classes.

On the other hand, the state — and hence the ruling elite — showed that it could be trusted, that a promise was a promise. Even if it was made centuries earlier, by and to people who were long dead. Even if it was in their power to terminate it at any time.

This was not the only event of its kind in the annual calender of the Doge. Over time the position became less political and more representational, so there was time in the schedule for symbolic acts to show that somehow “we’re all in the same boat,” even if they weren’t.

Then, tradition has inertia. It carries its own weight. The longer it lasts, the harder it is to change, even if it makes little sense centuries later.

Related articles

From the Curiosità Veneziane by Giuseppe Tassini:

- S. Pietro (Parrocchia, Campo, Ponte di) – Curiosità Veneziane

- Casselleria (Calle di) – Curiosità Veneziane

- Bande (Ponte, Calle delle) – Curiosità Veneziane

Bibliography

Renier Michiel, Giustina. Origine delle feste veneziane di Giustina Renier Michiel Volume primo [-sesto]. Editori degli Annali universali delle scienze e dell’industria, 1829.

Tassini, Giuseppe. Curiosità Veneziane ovvero Origini delle denominazioni stradali di Venezia. 1863.

Leave a Reply