The English gentleman John Evelyn spent almost one year in Venice and Padua in 1645–1646.

Venetian Stories

This post is an issue of our newsletter — Venetian Stories — which goes out every few weeks, to keep in touch and share stories and titbits from and about Venice and its history.

In his diary, he wrote about the Mercerie, which are a series of alleyways between the Rialto and St Mark, traditionally occupied by merchants of textiles.

One particular detail in his description of these streets in the mid-1600s struck me: the “innumerable cages of nightingales which they keep, that entertain you with their melody from shop to shop.”

Hence, I passed through the Mercera, one of the most delicious streets in the world for the sweetness of it, and is all the way on both sides tapestried as it were with cloth of gold, rich damasks and other silks, which the shops expose and hang before their houses from the first floor, and with that variety that for near half the year spent chiefly in this city, I hardly remember to have seen the same piece twice exposed ; to this add the perfumes, apothecaries’ shops, and the innumerable cages of nightingales which they keep, that entertain you with their melody from shop to shop, so that shutting your eyes you would imagine yourself in the country, when indeed you are in the middle of the sea. It is almost as silent as the middle of a field, there being neither rattling of coaches nor trampling of horses. This street, paved with brick, and exceedingly clean, brought us through an arch into the famous piazza of St. Mark.

Music in shops to attract clients and sell more is therefore nothing new. They did it in Venice in the 1600s.

Street vendors of songbirds

A century later, the artist Gaetano Zompini made sixty engravings of common people working on the streets of Venice.

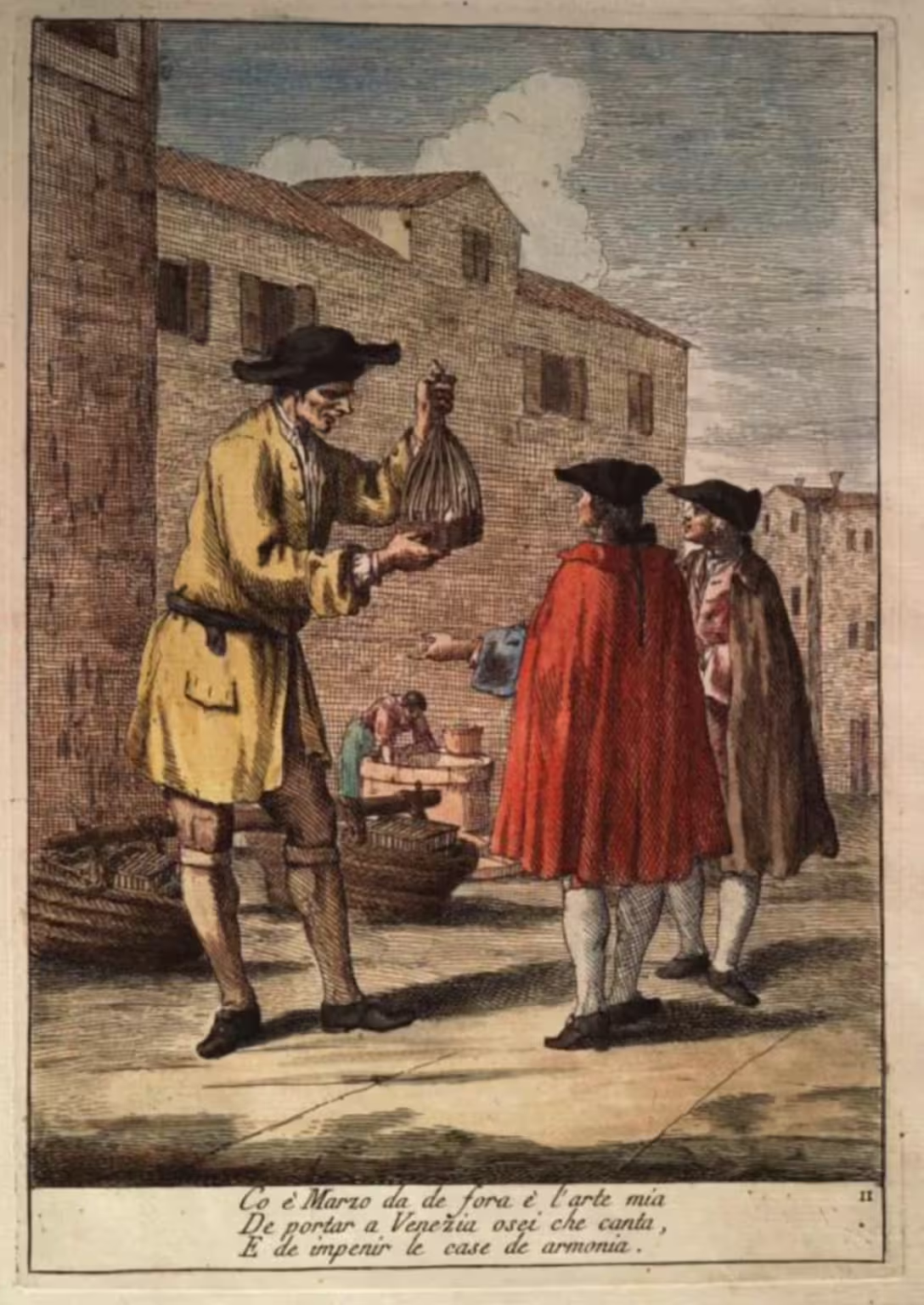

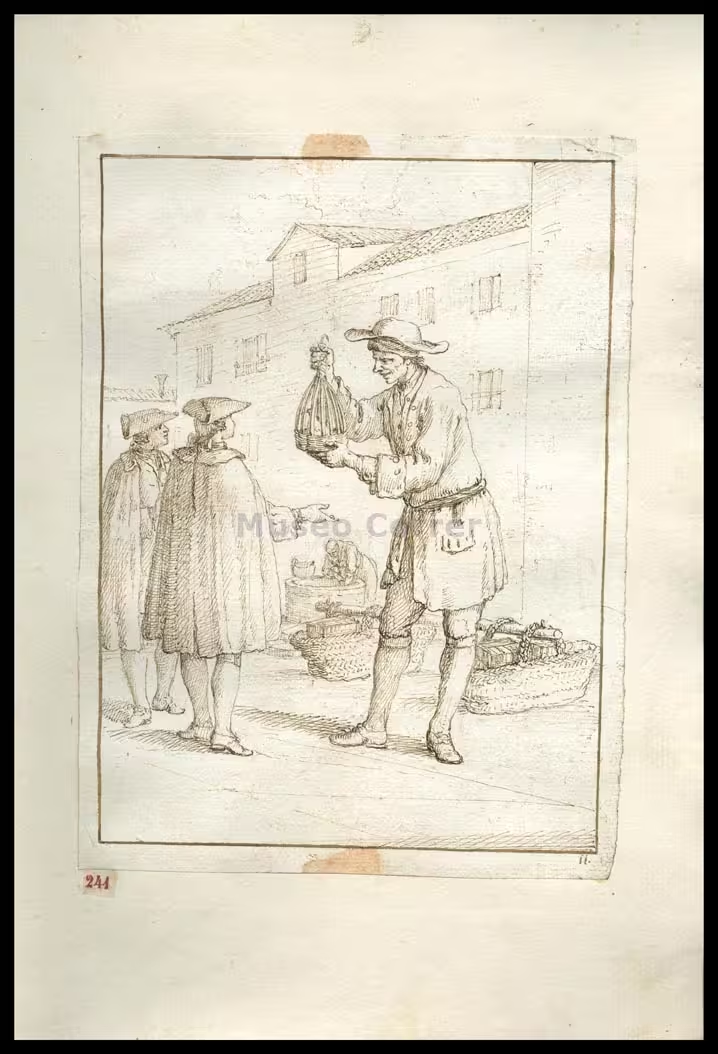

One of the engravings depicts a street vendor of live songbirds in cages.

The poem at the bottom of the print, in my translation from the Venetian, reads:

When March arrives, it is my trade

To bring from outside birds that sing

And fill the houses with harmony

The seasonality of the song of the nightingale is evident in the poem, but less so in Evelyn’s diary. However, if he kept his account chronological, the episode would be no later than early June (shortly after the Festa della Sensa).

Quacking around

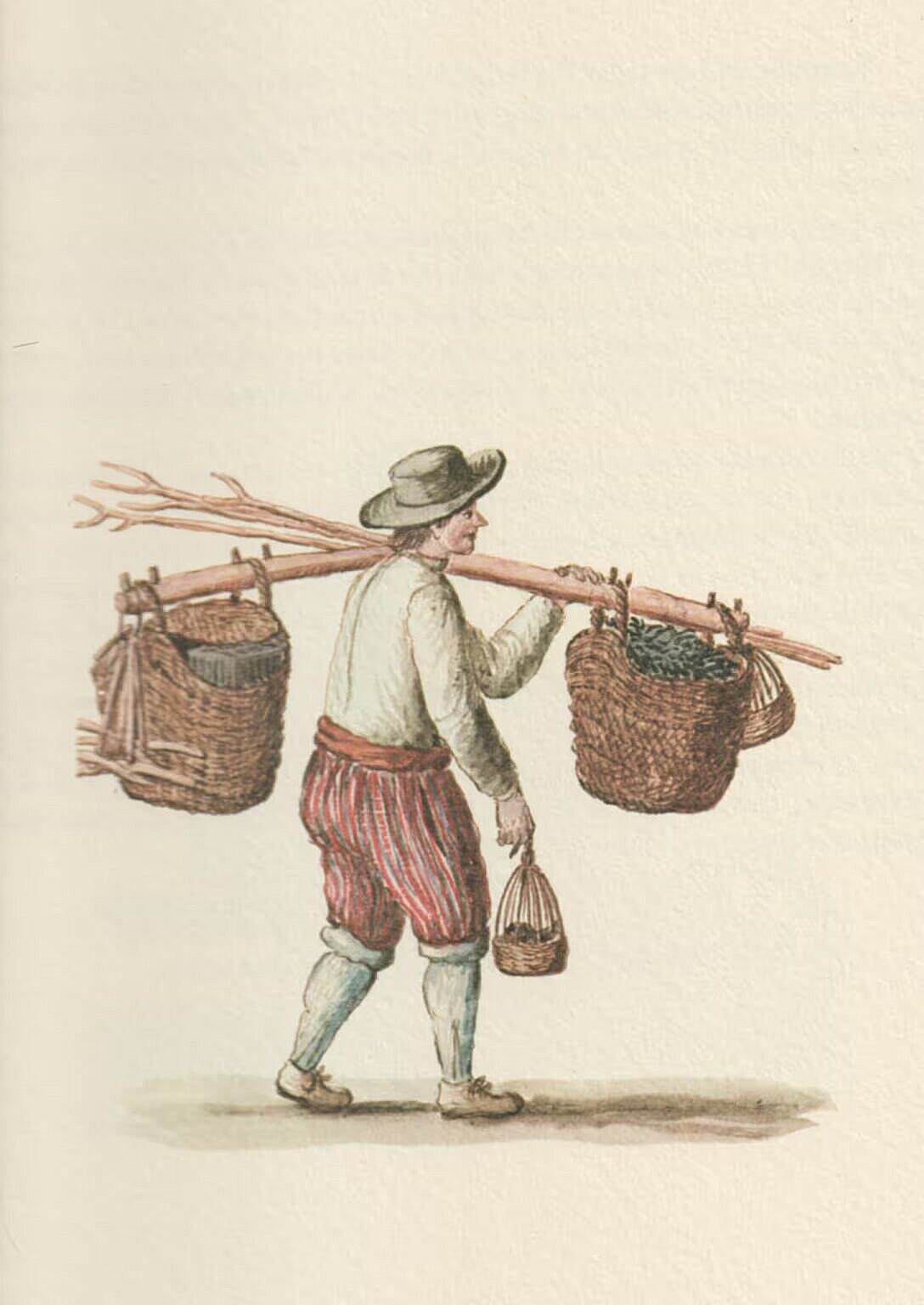

At the same time as Zompini, another artist also made images of common people. Giovanni Grevembroch worked for a Venetian nobleman, and made hundreds of watercolours for a four volume work on the way the Venetians dressed.

In the last volume, there is a painting of a peasant from the mainland selling live birds in Venice.

In the associated comment, Grevembroch wrote about peasants from the areas of Mestre, Chirignago and Spinea on the mainland:

They obtain greater profit in the contract of a prodigious quantity of small birds, domesticated since Autumn in small cages, which, feeling the Spring resurrected, with the beating of their wings, and with their singing, entice the Venetians to bring such a grateful entertainment to their Wives, and to the Children. The Sellers of these Birds usually take possession of two fixed places, that is, in sites adjacent to the Churches of S. Basso, and S. Giacomo, where the influx of People suspends other businesses, enjoying for some time the mixed whistling of various voices, and of the different colour of the innumerable species, as well as of the tireless male quails.

Grevembroch must have had a knack for puns, as many of his watercolours have ambiguous or humorous titles. He called this one “Il mermeo in giro.” The word marmèo (with an ‘a’) has several meanings. As an exclamation, it meant “No,” while as an adjective it signified stupid or daft. The substantive was then somebody not too bright. However, the expression “marmèo squaquarà” meant the song of the quails. The title can then mean either a slow-witted peasant or the song of the birds.

The dedication of the painting is to two named persons, from Spinea, who traded in songbirds, so maybe the nicer of the two interpretations of the title above is the more realistic. On the other hand, the dedications of Grevembroch might also be humorous rather than real.

Background music

It is evident from these three sources — even if they’re separated by a century — that live songbirds in cages were commonly used for entertainment and as background music, in homes and in shops. By the mid-1700s when Zompini and Grevembroch worked, the trade was clearly organised and regular.

Music has always been important, and playing an instrument was an essential part of a good education, just like singing and recitation. Performing and entertaining were valued social skills, as anyone who has read Jane Austen will know.

However, live music requires somebody to play. If that, for whatever reason, wasn’t an option, a nightingale in a cage could provide an alternative source of entertainment.

As for the shops, modern muzak — low-key background music in shops — supposedly induces people to spend more. This is why modern shops and malls usually have something inconspicuous playing in the background.

When Evelyn wrote in the mid-1600s that all the shops had birds in cages for their song, this knowledge must be quite ancient.

Nightingales only sing in the spring and early summer, so their music must have been a seasonal treat

Open questions

This little observation leads to more questions that answers.

How far back in time did such usage exist? Did shops in Roman times have nightingales singing in cages too? Did Byzantine shops?

Where did the Venetians get such an idea from? Or rather, was this a particular Venetian thing? The way Evelyn describes the phenomenon gives the impression that it was not common usage in England (or elsewhere he travelled) to have songbirds in cages in shops.

While nightingales appear abundantly in mythology, literature and folk-tales, I haven’t found other references to their use as background muzak in shops.

Bibliography

Evelyn, John. Diary and correspondence, vol. 1. London : Henry Colburn, Great Marlborough Street, 1850.

Grevembroch, Giovanni. Gli abiti de veneziani di quasi ogni eta con diligenza raccolti e dipinti nel secolo XVIII, orig. c. 1754. Venezia, Filippi Editore, 1981.

Zompini, Gaetano. Le arti che vanno per via nella città di Venezia inventate ed incise da Gaetano Zompini, Aggiuntavi una memoria di detto autore. Venezia, 1785.

Leave a Reply