The English gentleman John Evelyn (1620-1706) visited Venice and Padua from May 1645 to March 1646. He was in his mid-twenties then, on the classic educational Grand Tour in Italy, which was probably a wise choice.

Venetian Stories

This post is an issue of our newsletter — Venetian Stories — which goes out every few weeks, to keep in touch and share stories and titbits from and about Venice and its history.

John Evelyn lived in interesting times, but he mostly stayed clear of active participation in the main struggles of his time. He was, however, a declared royalist, and entered into correspondence with Charles II during his exile. Consequently, he had access to the royals after the Restoration.

The diary

He kept a diary for much of his life, even if some parts were probably compiled later from notes and almanacs.

He is less famous than his contemporary Samuel Pepys, as his diary was published much later. The manuscript remained with the family until the 1800s, when it was finally edited and published.

I have used an edition from 1850, but there are many editions, of which several a digitized and easy to find online.

His Grand Tour of Italy took him around much of the peninsula, but he clearly dedicated much time to Venice and Padua. According to himself, he even rushed their arrival in Venice because they wanted to see the pomp of the Festa della Sensa — the Feast of the Ascension — with the particular marriage ceremony with the Sea.

The following are some picks from the almost twenty-five pages Evelyn dedicated to his stay in Venice and Padua. There’s much more in the complete text, with notes and explanations, elsewhere on the website.

Pomp and circumstance

The Republic of Venice was ancient, even to an Englishman in the 1600s, and many of the official ceremonies must have seemed as odd and out of place then, and parts of the British monarchy does today.

As mentioned, Evelyn was keen on the Festa della Sensa — the traditional celebration on Ascension day:

The Doge, having heard mass in his robes of state (which are very particular, after the eastern fashion), together with the Senate in their gowns, embarked in their gloriously painted, carved, and gilded Bucentora, environed and followed by innumerable galleys, gondolas, and boats, filled with spectators, some dressed in masquerade, trumpets, music, and cannons. Having rowed about a league into the Gulf, the Duke, at the prow, casts a gold ring and cup into the sea, at which a loud acclamation is echoed from the great guns of the Arsenal, and at the Liddo. We then returned.

The position of Doge harked back to when Venice was still a Byzantine province, and some of the ceremonial was still very ‘eastern’ for a ‘western’ eye. Evelyn wrote more than two centuries after the last Byzantine emperors had set foot in Western courts.

The Bucindoro was the ceremonial boat used by the doge for the main events, such as the Festa della Sensa. There were several through the many centuries of Venice, but the last was burned and destroyed in 1797.

The core of the Festa della Sensa — the throwing of a golden ring into the sea — represented a symbolic marriage between Venice and the Sea, but in a patriarchal way. The marriage was seen as domination and control, where Venice asserted rights and ownership over the sea, as a man would over his wife.

The feast was a display of imperial power and control. The fortresses of the Lido, the Castel Vecchio and the Castel Novo played an important part of this feast, and many of the cannons mentioned no doubt fired from there.

The peculiarity of Venice

The peculiar character of Venice was much more evident back then. Now, Venice is very much a pedestrian city, and everybody walks everywhere.

It was not so in the 1600s. There were more canals, and there were far fewer bridges. You could go to very few places without a boat.

… taking a gondola, which is their watercoach (for land ones there are many old men in this city who never saw one, or rarely a horse), we rowed up and down the channels, which answer to our streets.

For someone like Evelyn, coaches and horses were as much a part of daily life as cars are today, and meeting people who never saw a coach or a horse was very unusual.

The Venetian women

Evelyn apparently had a problem with Venetian women, and especially their footwear:

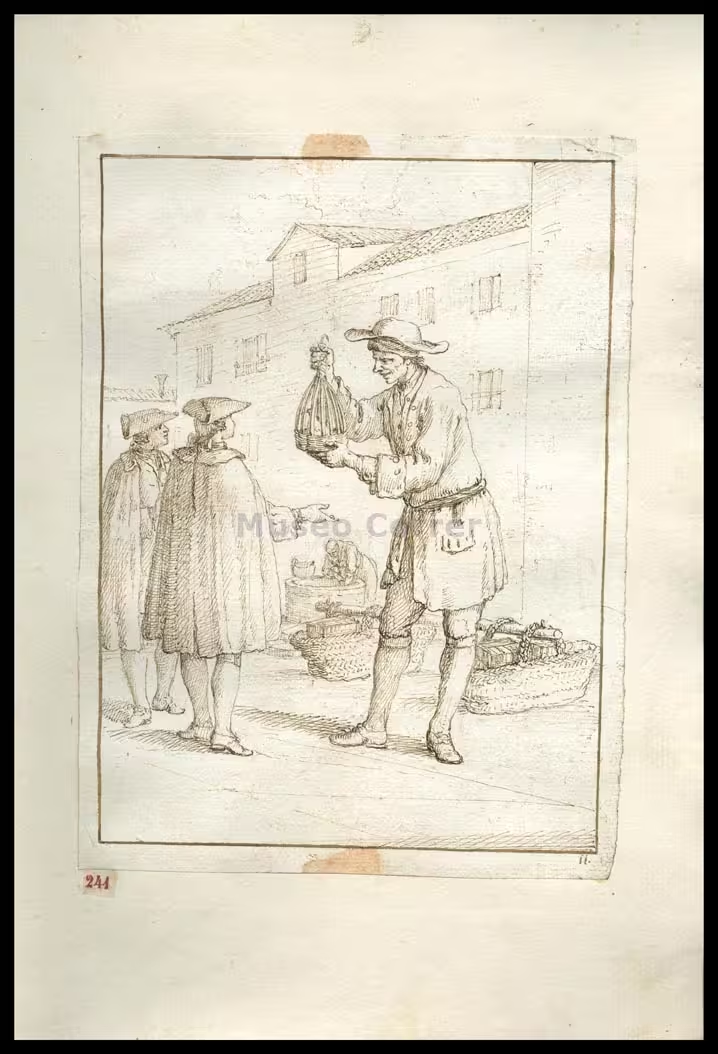

The noblemen stalking with their ladies on choppines ; these are high-heeled shoes, particularly affected by these proud dames, or, as some say, invented to keep them at home, it being very difficult to walk with them ; whence one being asked how he liked the Venetian dames, replied, they were mezzo carne, mezzo legno, half flesh, half wood ; and he would have none of them. The truth is, their garb is very odd, as seeming always in masquerade; their other habits also totally different from all nations.

They wear very long crisp hair, of several streaks and colours, which they make so by a wash, dishevelling it on the brims of a broad hat that has no crown, but a hole to put out their heads by ; they dry them in the sun, as one may see them at their windows.

In their tire, they set silk flowers and sparkling stones, their petticoats coming from their very arm-pits, so that they are near three quarters and a half apron ; their sleeves are made exceeding wide, under which their shift-sleeves as wide, and commonly tucked up to the shoulder, showing their naked arms, through false sleeves of tiffany, girt with a bracelet or two, with knots of points richly tagged about their shoulders and other places of their body, which they usually cover with a kind of yellow veil, of lawn, very transparent. Thus attired, they set their hands on the heads of two matron-like servants, or old women, to support them, who are mumbling their beads.

It is ridiculous to see how these ladies crawl in and out of their gondolas, by reason of their choppines, and what dwarfs they appear, when taken down from their wooden scaffolds;

The choppines are called calcagnette in Venice. They are plateau sandals, sometimes very tall, but usually around 10-20cm.

The daring engraving above is from the late 1500s, showing a courtesan with a fold-up part to reveal her knickers, and her calcagnette.

Needless to say, it was not unusual for women to get hurt wearing such shoes.

Sources

The diary, and much of the correspondence of John Evelyn, has been published several times, and many editions are available online digitized, for example here.

Bibliography

Evelyn, John. Diary and correspondence, vol. 1. London : Henry Colburn, Great Marlborough Street, 1850.

Leave a Reply