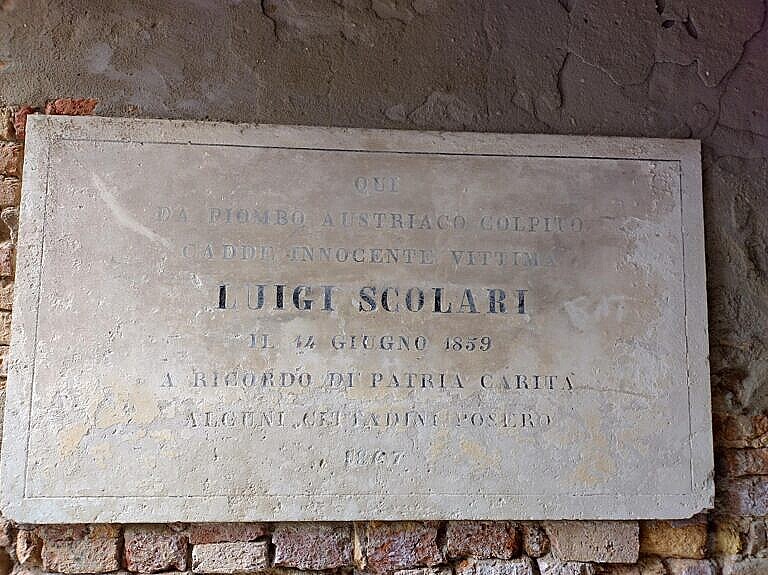

In central Venice, on a wall in a little used passageway close to San Fantin, there’s a barely readable plaque. It is an inscription from 1867 which commemorates a Luigi Scolari, killed by the Austrians on June 14th, 1859.

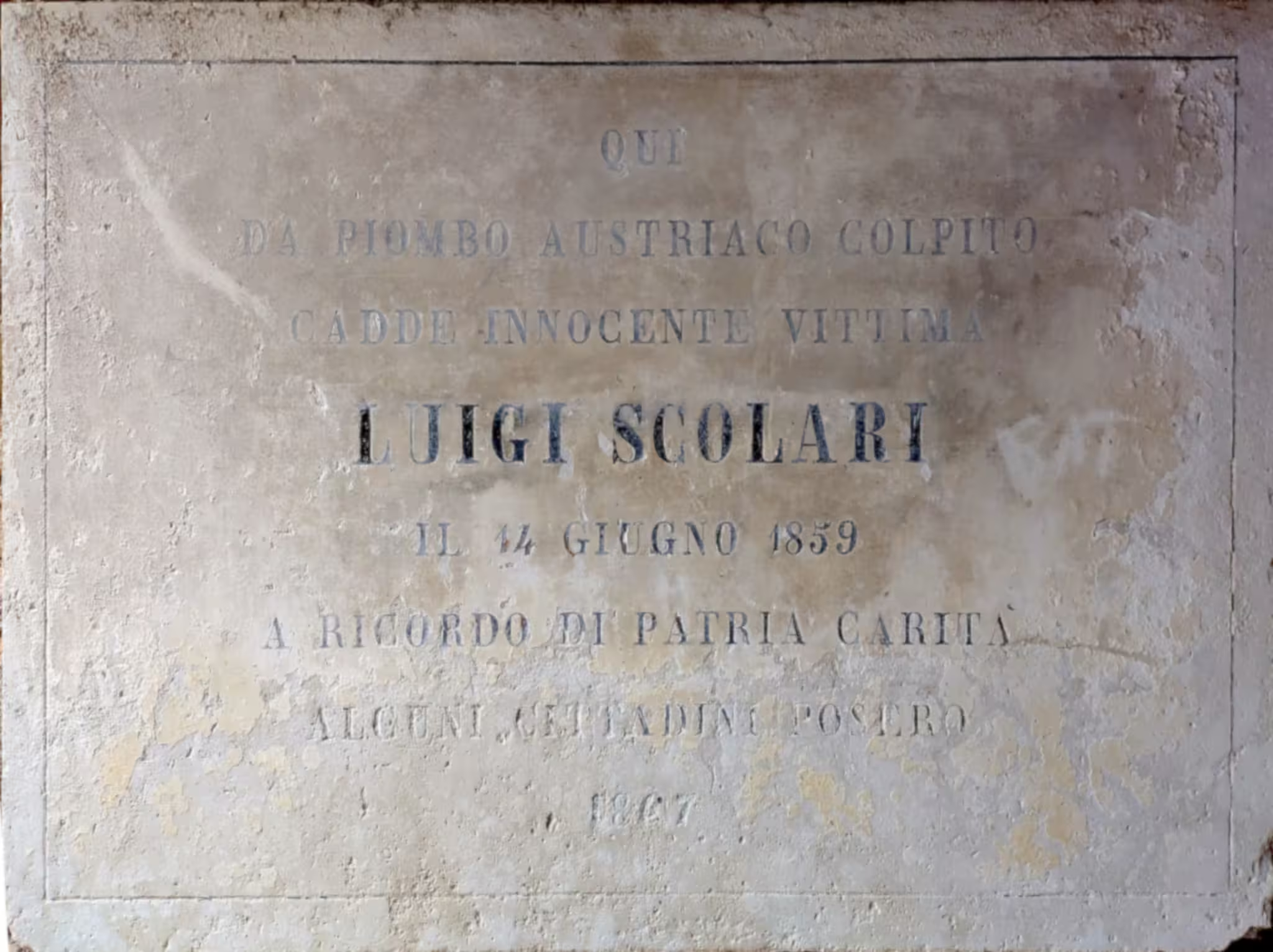

QUI DA PIOMBO AUSTRIACO COLPITO CADDE INNOCENTE VITTIMA LUIGI SCOLARI IL 14 GIUGNO 1859 A RICORDO DI PATRIA CARITA’ ALCUNI CITTADINI POSERO 1867

HERE HIT BY AUSTRIAN BULLETS FELL INNOCENT VICTIM LUIGI SCOLARI ON JUNE 14TH 1859 IN MEMORY OF SACRIFICE TO THE FATERLAND SOME CITIZENS DEDICATED 1867

What happened in Venice in June, 1859?

The unification of Italy

What happened elsewhere was the Second Italian war of Independence.

Italy was not yet one single nation state. There was, however, a movement in that direction in many of the smaller states on the Italian peninsula.

The Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont publicly stated in early 1859 that it could not ignore the popular cries against the Austrian oppression in Lombardy and the Veneto, and started to mobilise.

The Austrian-Hungarian Empire reacted with an ultimatum demanding that Sardinia-Piedmont stood down its army.

Sardinia-Piedmont refused, which meant war. In April and early May or 1859 Sardinia-Piedmont fought alone, but then France under Napoleon III joined the war.

The war went well for the Sardinian-French side, which won several skirmishes and battles in May and June. On June 4th the French defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Magenta, which opened Lombardy to the Sardinian-Piedmont army. They reached Milan on June 7th. The day after Emperor Napoleon III and King Vittorio Emanuele II entered the city triumphantly.

Nationalist hope in Venice

Venice was not a part of all this, which happened quite a bit away.

However, the news of Austrian military defeats reached Venice, and the conquest of Lombardy gave the Italian minded nationalists hope.

A French/Sardinian navy appeared off Venice, visible from the church towers and some rooftops.

On the morning of June 14th there was a buzz around the city of Venice. There were very few Austrian soldiers around. At a high school (ginnasio liceale) at Santa Catarina the children of Austrian officers didn’t come to school. Some of the more Austrian aligned teachers also went missing.

In the afternoon, a shout outside of Viva l’Italia! had many students run into the streets. Believing the Austrian rule was over, they gathered in the streets, and many others joined them in celebration. If the Austrian had lost Lombardy and Milan, surely they had to abandon Venice too.

A handful of students, lead by the twenty year old Luigi Scolari, ran into a group of Croatian soldiers in the Piscina de la Frezzeria close to San Fantin.

The soldiers fired, and hit Scolari in the leg. The others ran, and left Scolari there on the ground bleeding profusely.

It took a while before somebody gathered the courage to pick him up. They took him to the Ospedale Civile, where he died later that night.

The Austrian authorities did not allow the grieving and devastated family to put up any kind of announcement of their sons death.

No liberation of Venice

The war ended with the Armistice of Villafranca on July 11th, negotiated between Napoleon III and Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary. It was later formalised as the Treaty of Zurich in November, 1859.

The Austrians accepted the loss of Lombardy to the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont, but the Veneto remained under Austrian control.

The armistice crushed the hope of the Italian nationalists in Venice. It would remain under Austrian rule until after the Third Italian war of Independence six years later, in 1866.

The plaque controversy

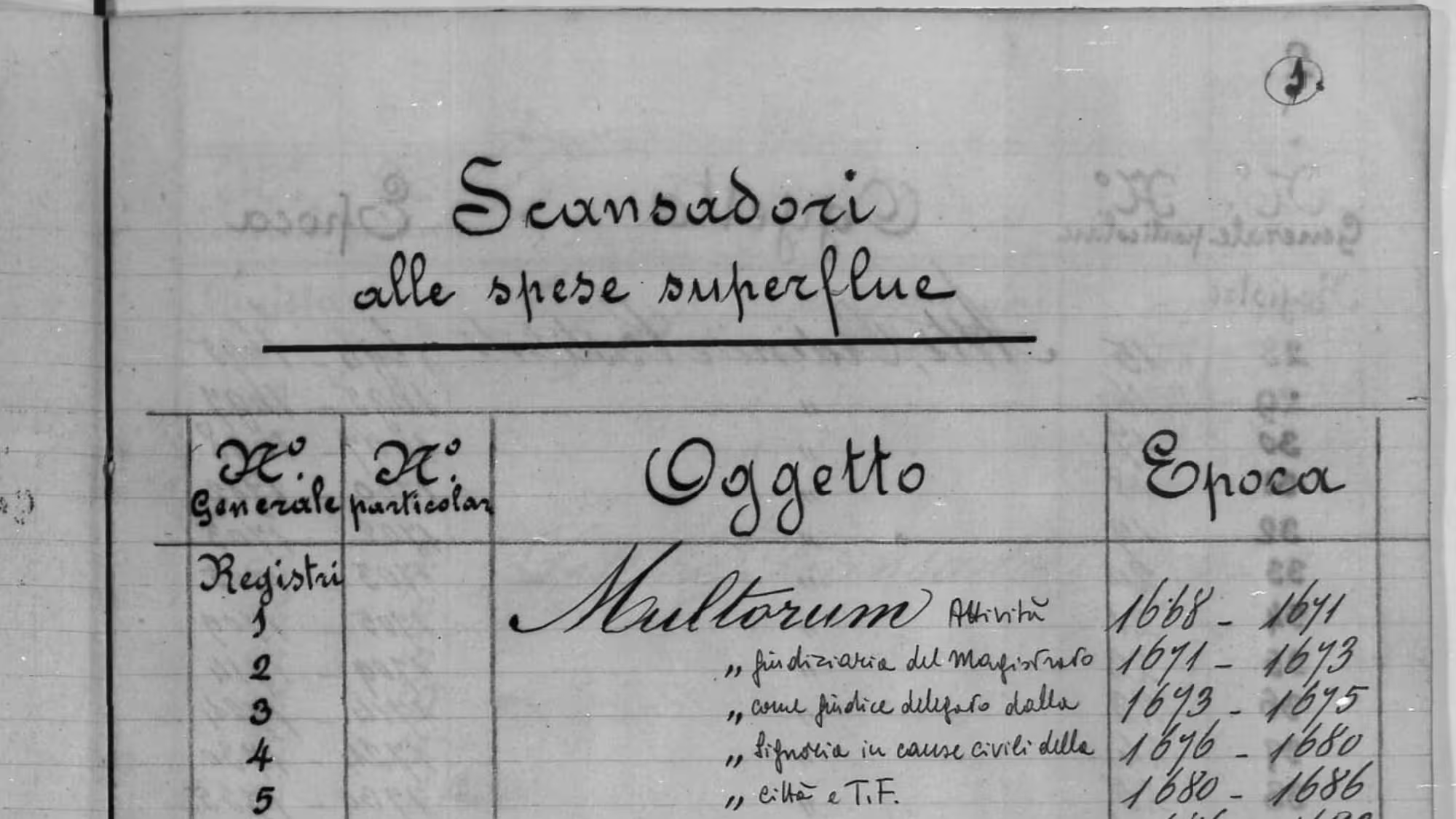

Luigi Filippo Bolaffio — a school companion of Scolari — published in 1867 his recollections of that fateful day. It is not easy to find, but the original Italian text is here and my translation into English here.

In it he recounts how he and three others organised a collection of funds to put up a plaque to commemorate Luigi Scolari, on the place where he was shot.

In Bolaffio’s account there’s one more line to the text on the plaque that we see today. He even repeats the line a second time in his account, in cursive, which gives that impression that for him those words were important.

The original plaque had this line before the current penultimate line:

AD ESECRANDA MEMORIA DEI CARNEFICI

IN CURSED MEMORY OF THE EXECUTIONERS

This line was too much for some, who worried that the Austrians might take offence, and the prefect of Venice (the highest representative of the Italian State in each province) intervened (Tassini 1863, translated entry here).

Bolaffio was in his early twenties in 1867 (he was born in 1846), and the prefect, Luigi Torelli, had been a member of the Chamber of Deputies of the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont from 1849, Senator of the Kingdom of Italy from 1860, and prefect of the Province of Venice from 1867.

The offending line was removed from the plaque.

Leave a Reply