The Venetian ghetto is the first ghetto ever, at least with the name ‘ghetto’ because that word comes from the Venetian language.

It has, however, more to do with medieval arms production than with the Jewish population of Venice.

Guns and arms

The area now known as the Ghetto Vecchio was occupied by foundries and smithies in the Middle Ages.

Giuseppe Tassini, whose Curiosità Veneziane is always a good starting point, mentions a legal document from 1306 which refers to a named official of the Ghetto. Consequently, there was a Ghetto in Venice then, and as it was an institution with a leadership and an administration, it had probably been there for some time.

Tassini also recounts a testimony which recalled the area of the early 1400s: There were more than twelve furnaces in El getto, and they cast copper there. Three masters managed the place, ‘like other offices,’ and there were scribes and clerks, and over a hundred workers living nearby.

The importance for the Venetian state of the foundries and smithies of the Ghetto lay in arms production. In the late 1300s and in the early 1400s, that also meant the casting of bombarde.

The bombard is some of the earliest European artillery. It was usually a kind of massive mortar for hurling huge stones at castles walls, fortifications, or, in the case of Venice, at wooden warships. They were the successors of earlier siege machinery, like catapults, just using gunpowder to propel the stone projectile, rather than various mechanical contraptions.

Etymologies

The word used for ‘casting’ came from late Latin iectāre, which means to throw, sling, hurl or cast. We have the classical form of the word in Caesar’s famous alea iacta est — the die is cast — when he crossed the Rubicon.

The word iectāre then became gettare in Italian and jeter in French. English has words like jet, jettison, and jetsam through Old French.

In medieval Venetian the ‘g’ became hard, leading to the word gheto and later the Italianized word ghetto.

In relation to foundries it meant pouring molten metal into a mould.

On a side note, medieval metallurgy wasn’t capable of casting an entire cannon in one piece. They therefore made a series of slightly wedge-shaped iron staffs, which together could form the cylindrical tube of the gun. To hold them together, they fitted iron rings around the cylinder.

Iron expands when hot, and contracts when it’s cooling. The craftsmen made the iron rings precisely, so they could just fit them over the tube when very hot. As the iron ring cooled down, it contracted and held the staffs tightly together.

This is just like how you make a wooden barrel, which is why guns, even today, have barrels.

Abandonment

By the mid-1400s the ghetto was all but abandoned.

We don’t know why the activities moved elsewhere. Maybe the reason was the fire hazard of the furnaces, or simply that the production worked better within the Arsenale (from Arzanà, another Venetian word). The Arsenale of the 1400s was a far larger place than the Arsenale of the early 1300s, and the production of guns moved inside the walls of the Arsenale.

The island of the Ghetto Nuovo passed in the hands of the De Brolo family, which tried to build a housing estate there. The works started, and the three well-heads of the Campo del Ghetto Nuovo all carry the coat of arms of the De Brolo family.

There’s a paper trail, because in the 1460s a conflict between the parishes of San Geremia and San Marcuola engulfed the project. Both parishes wanted authority over the parishioners of the new area.

The development project for whatever reason never finished.

Sabellicus, who published a description of Venice in 1502, wrote that the open area called (writing in Latin) the jactum, i.e., the origin of the word ghetto, was in large part destroyed or abandoned.

He also noted that there were two distinct parts of the ghetto. A newer part, the current Ghetto Nuovo, surrounded by water on all sides, and an older part, the Ghetto Vecchio, located between buildings and connected to the newer part by a bridge.

The Jewish quarter

Persecutions and expulsions uprooted Jews from many countries in Europe in the late 1400s. This happed for example in several German cities in 1470, in Spain in 1492 and in Portugal in 1497.

Many of these Jews found refuge in Venice. In spite of much discrimination, the Jews weren’t actively persecuted, and Venice was a relatively safe place for many Jews.

In 1516 the Venetian government assigned the area of the Ghetto Nuovo to the Jewish population of Venice, and in 1544 the Ghetto Vecchio too. The word ghetto, however, remained in use for both areas.

It was not a matter of altruism, though. Large parts of the Venetian aristocracy looked at the Jews with suspicion, and more than to help Jewish refugees, the desire was more to isolate and control the entire group.

Whatever the original reasons, the Venetian ghetto is the centre of Jewish life and worship in Venice to this day.

Ghettos elsewhere

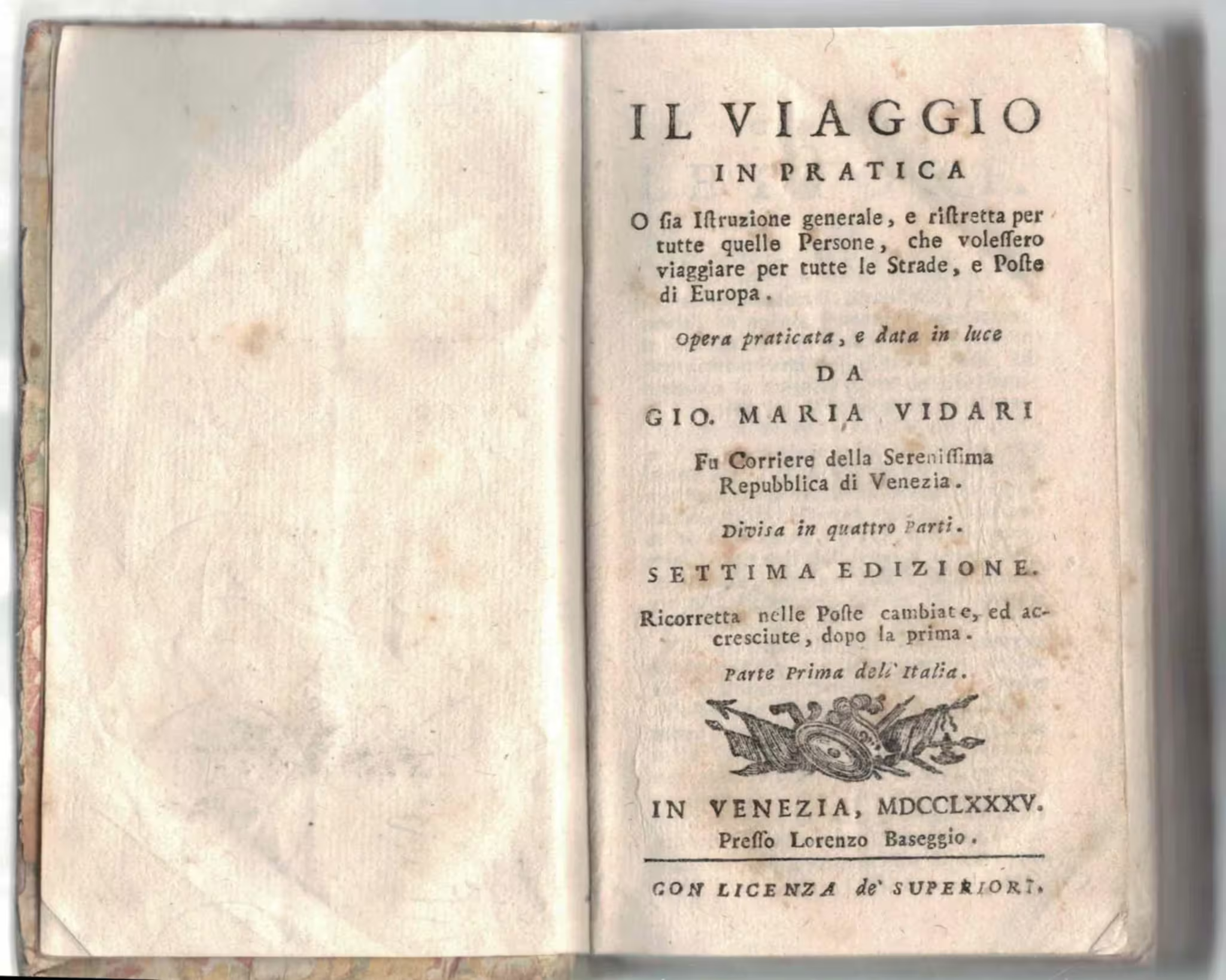

Venice was for much of its history a commercial and cultural centre, where lots of people from Western Europe and the entire Mediterranean basin crossed roads.

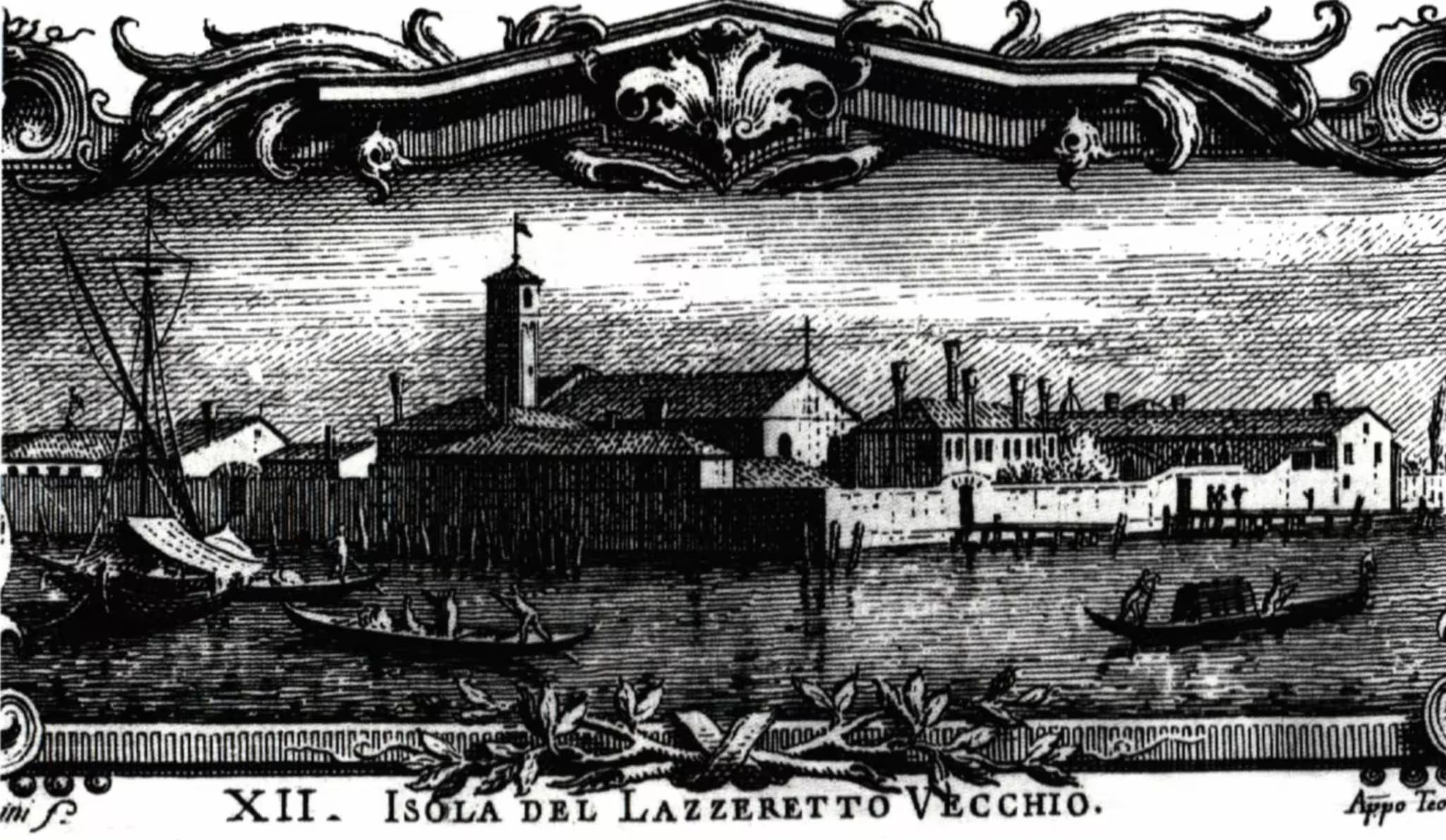

Venetian ideas and innovations soon spread to other places, like with the lazzaretti.

In many other places around Europe they started using the word ‘ghetto’ to indicate the Jewish quarter, so ghettos appeared in other cities and in other languages.

When Europeans moved to the Americas, the word ghetto moved with them, but it changed meaning towards a more general concept.

Rather than being an area specifically for the Jewish population, it became an area for any kind of minority.

Therefore, in the Americas, there are African-American ghettos, Hispanic ghettos, Chinese ghettos, and ironically even Italian ghettos, inhabited by immigrants from Italy.

More about Venetian words

Venetian words that are still in common use include arsenal, ballot, ciao, ghetto, lazzaretto, and quarantine.

Leave a Reply