The Maggior Consiglio – or the Great Council – was the highest authority of the Venetian Republic.

While the name could give the impression that it was an elected body, it was not. The Maggior Consiglio was, in fact, the entire electorate.

The Res Publica

The word republic comes from the Latin res publica which means the public matters or the public affairs.

An important question every republic must answer is then: who is, and who isn’t the public? Or in other words, who gets the vote?

The early Venetian Republic didn’t have a well-defined answer, due to the ad hoc way the state started.

The first doges were simply acclaimed by an assembly of the ‘people’, without a formalised voting process. The assembly was called the Concio or concione.

Here the ‘people’ most likely means the wealthiest citizens whose families had been around for ‘long enough’.

The Minor and the Major Council

The complete assembly of the wealthiest citizens was large and unwieldy, so early on they elected a council of ‘sages’ – the Consilium Sapientium – to counsel, assist and control the doge.

This was formalised as the Minor Council – il Minor Consiglio – in 1142. Consequently, from 1172, the larger assembly became known as the Consiglio Maggiore.

The main function of the Maggior Consiglio remained the election of the doge, which now took place in a more regulated and formalised context.

Within the Venetian Republic, only those on the Maggior Consiglio had a say on matters of the state. As such, the council was not an elected body. It was the entire electorate.

Who’s in and who’s out?

Venice had no clear answer to the basic question of who was on the council and who wasn’t for a long time.

Being on the Maggior Consiglio gave political influence, and it was a source of social status.

However, having a group of men from ‘old’ and ‘wealthy’ families can lead to all sorts of issues. An ‘old’ family in economic decline is unlikely to give up their privileges voluntarily, and a very wealthy, but less ‘old’ family would likely demand membership anyway due to their riches.

The council finally confronted the problem in 1297 which a decision called the serrata del consiglio – the closing of the council.

Membership became entirely hereditary. Only descendants of those who had been on the council in the four previous years could henceforth become members of the council.

In 1315, the council created the Golden Book, to keep a registry of all potential members. All male members of the selected families were entered after their 18th birthday.

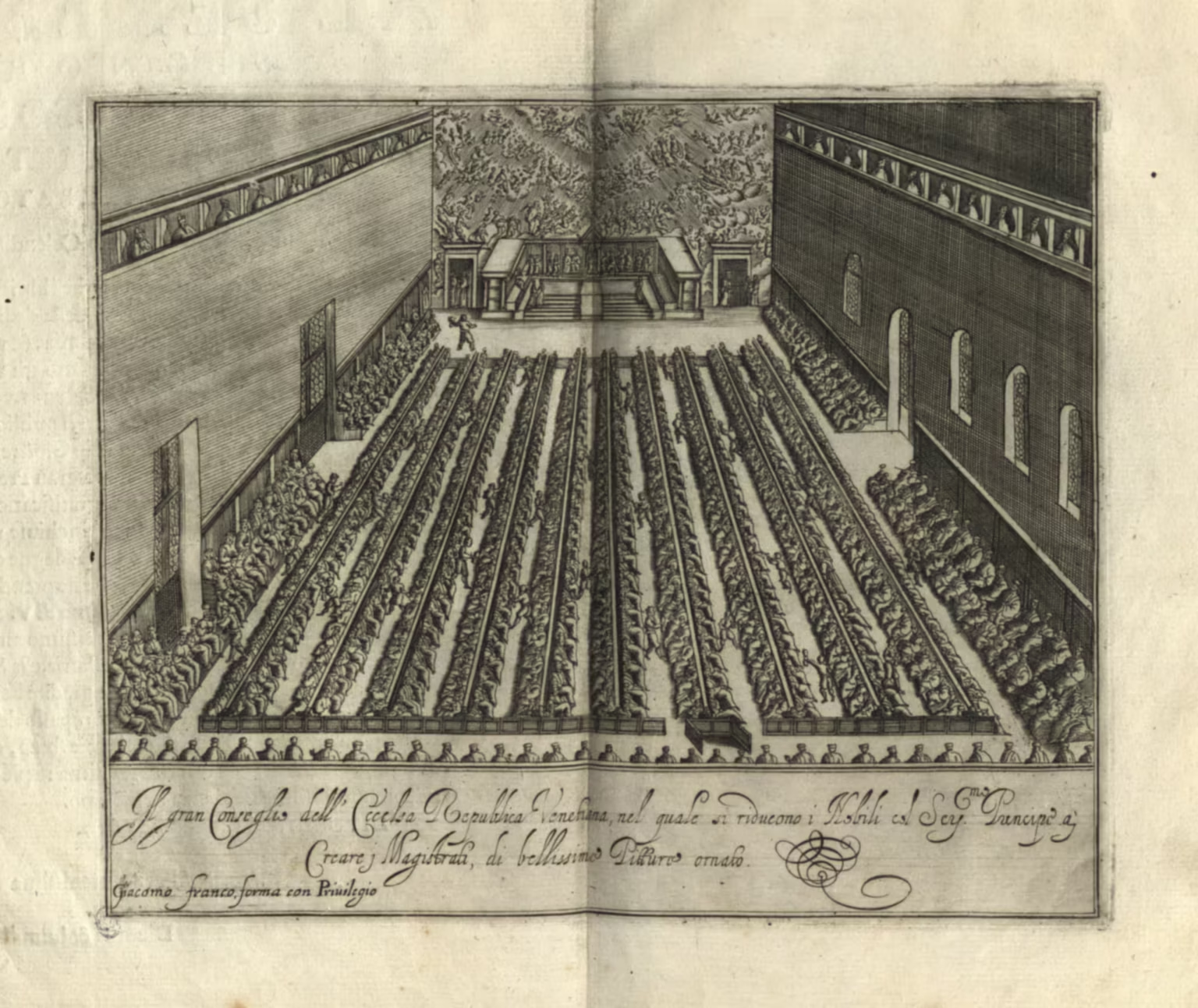

A huge council

The closing of the council didn’t diminish its size.

The Maggior Consiglio normally had well over two thousand members, and at times almost three thousand. It made voting procedures slow and cumbersome.

The population of the city was probably around two hundred thousands, so the rule of the state was literally in the hands of 1% of the population.

Over the centuries, some patrician families declined in wealth, and other non-patrician families grew richer.

In times of need, for example in cases of protracted wars, access to the Consiglio Maggiore was sold to fill the coffers of the state.

Poorer patrician families often sold their votes to get some income. This usually happened on an area of the Piazza San Marco called the Broglio, hence the term ‘imbroglio‘ which English has borrowed from Italian.

The End

In May 1797, when Napoleon’s troops approached Venice, the Consiglio Maggiore met and voted to accept the abdication of the last doge Ludovico Manin, and afterwards to dissolve itself.

In the face of the imminent French conquest of the city and the state, the Venetian aristocracy chose to shut down the state on their own.

Related articles

- The Doge

- The Barbarèla

- Doges of Venice

- The Republic of Venice

- Citizen of the Republic of Venice

- The Venetian Nobility

- The Venetian constitutions

- State institutions of the Republic of Venice

- Chronology of major Venetian state institutions

- Maggior Consiglio — Lessico Veneto

- Maggior Consiglio — ASV Indice

Leave a Reply