What did it mean to be a citizen of the Republic of Venice?

The answer to that question very much depended on what lot you drew in the great lottery of birth.

The conditions of birth were all-important for what a person could be and do in life.

A hierarchy of citizenship

Ancient Venice was a class society, and which class a person belonged to was mostly, but not entirely, decided at birth.

The great divide in status was between the nobility and the cittadini (citizens), but the system was more complex than that.

The most important groups were:

- Patricians — that is, the aristocracy or nobility

- Original citizens

- Citizenship de intus et de extra

- Citizenship de intus tantum — or popolani

- People from the Dominio de Terra Ferma

- Foreigners

- Jews

The Patricians — Nobil Uomini

The patrician class was for most of the history of Venice the rulers of the state.

In the Res Publica they were the public — only patricians had a say in state affairs.

If the divide between patricians and commoners was less marked in the earliest times, it became much more so with the establishment of the Maggior Consiglio in the 1100s. Henceforth, only members of the Greater Council had any say in state matters, and that membership was closely guarded.

Then, with the Serrata del Consiglio in 1297, the divide became even more rigid, and above all, entirely hereditary.

Since 1315, all Nobil Uomini were inscribed in the Libro d’Oro — the Golden Book — which was kept in the Sala del Scrigno in the Palazzo Ducale.

All together, for most of the history of Venice, this class consisted of circa five thousand persons out of the 100–150 thousand residents of Venice.

The Greater Council — the adult, male members of the aristocratic families — had around two thousand members. It never reached three thousand, and at the end of the Republic the council had only around twelve hundred members. In the very last vote, on May 12th, 1797, less than half of that participated.

The patricians were not ‘citizens.’ The word cittadini always referred to the lower classes. They were styled nobil uomo and nobil donna.

Original citizens — Cittadini Originari

The cittadini originari were thought of — as the name also implies — as the descendants of the non-noble, original inhabitants of Venice. As such, they were as real Venetians as the patricians, but less privileged due to an inferior birth.

The rules of belonging to this group were formalised, just as for the patricians.

The requirements to be a legally recognised cittadino originario were to be born in Venice as legitimate offspring, not living of menial work (arte meccanica as opposed to arte liberale), being inscribed in the census and not having a criminal record, for at least three generations.

The cittadini originari were inscribed the Libro d’Argento — the Silver Book — since 1315, just like the patricians had the Golden Book.

The original citizens had access to a series of positions within the state administration, all the way up to the Cancelliere Grando, who ranked almost as high as the doge. They could be lawyers, notaries, secretaries to the Senate and other offices, and messier grando, a position akin to head of the police.

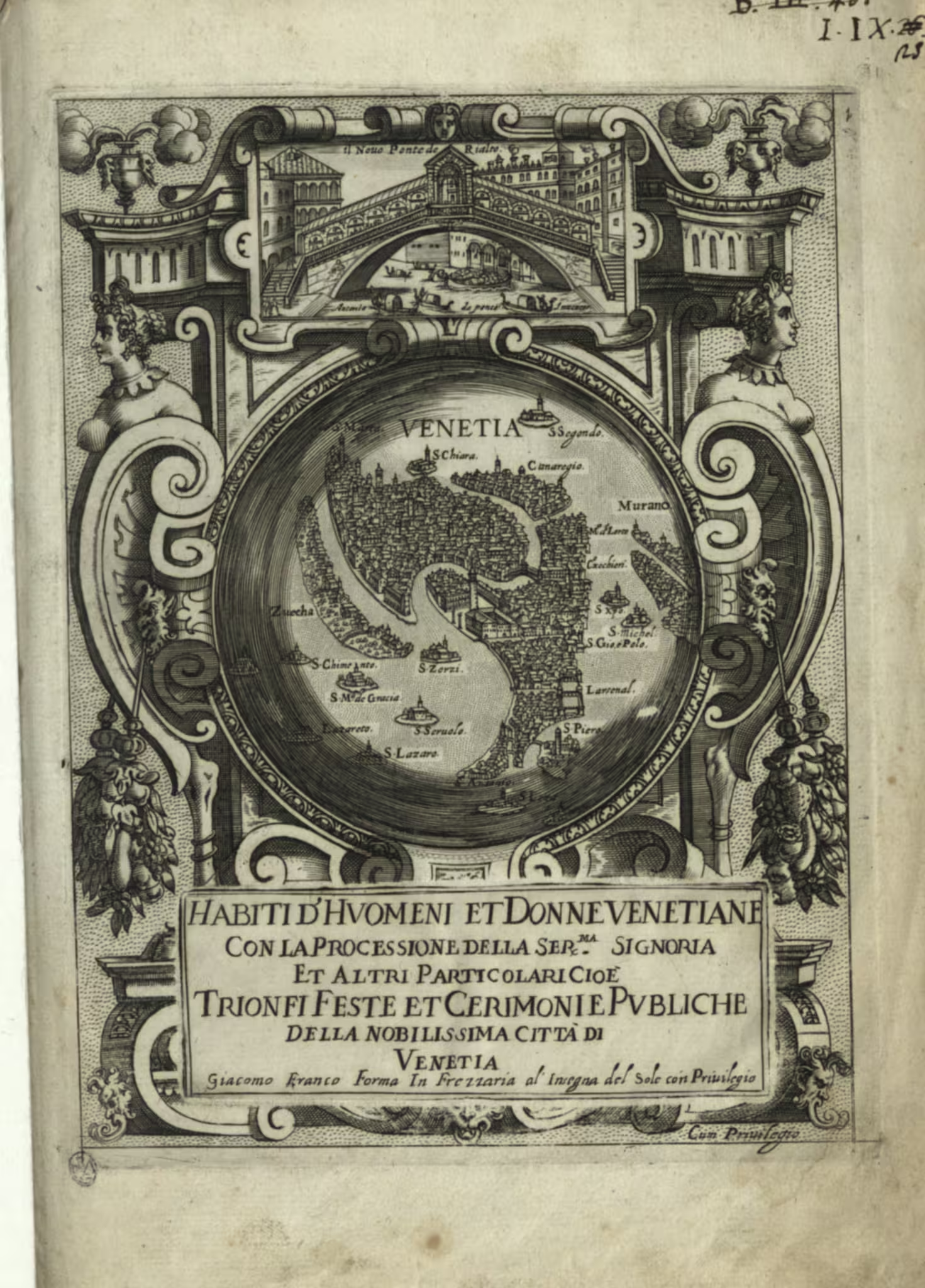

People from Torcello, and glassmakers from Murano, were traditionally considered original citizens.

Citizenship de intus et de extra

The citizenship de intus et de extra — within and beyond — was close to being an original citizen, but it could be conceded to foreigners by the Senate and the Provveditori di Comùn, after the application was processed by the Avogadori di Comùn.

The de intus part meant that they were considered Venetian citizens within the city of Venice — or within the Dogado — while de extra meant they could engage in commerce abroad with the privileges, rights and protections offered to citizens of the Republic of Venice.

This status did not, however, give access to some of the higher ranking positions within the state, which were available to original citizens. People of foreign birth — and therefore with foreign family bonds — were considered potentially less loyal to the state than those who were Venetian born through several generations.

Citizenship de intus tantum — or popolani

The vast majority of the population of Venice did menial work. There were not, therefore, cittadini originari, no matter for how many generations they had lived in Venice.

They were popolani — of the common people.

The formal name for this status was cittadini de intus tantum, which meant that their rights were limited to within the city or the Dogado.

They did not have access to any particular roles in the state, and they could not engage in overseas commerce. One privilege they did have, was to participate in the social life of the Scuole Grandi — the Great Schools — which were important charitable institutions whose members often participated in festivities and processions along with the higher ranking social groups.

Many of the smaller scuole in Venice were organisations of and for the popolani — they were guilds of craftsmen.

The de intus tantum status could be conceded to foreigners — often skilled craftsmen — who had lived and worked honourably in Venice for a number of years.

Foreigners and non-citizens

Being a legal citizen of Venice gave some rights and privileges, depending on your class, but there were also many non-citizens in the city.

People from the Dominio de Terra Ferma

The mainland was never considered a part of Venice as such.

Members of the nobility of cities within the mainland possessions of Venice — the subject cities of the Dominio di Terra Ferma — were at most considered original citizens in Venice, even if they were aristocracy in their home cities.

Commoners from the Venetian dominions were — if they came to Venice — generally considered foreigners.

Foreigners

People from outside the Venetian dominions were simply forestieri — foreigners.

Since Venice was a trading centre — and generally a wealthy place with many opportunities — there were quite a few of them.

The Jewish population

The Jewish residents of Venice were initially considered foreigners.1

They couldn’t partake in any activities reserved for the nobility or the original citizens — because they were neither. Also, since they couldn’t be members of the guilds, they were de facto excluded from most regulated crafts.

In 1534, they received permission to form an association, just like other citizens de intus had schools, confraternities, fraglie and others. This became the Università degli Ebrei, and represented a sort of recognition of their presence in Venice.2

They were still not citizens, but neither were they entirely foreigners.

Law and class

The law was not equal for everybody in the Republic of Venice. Some were definitely more equal than others.

A law of 1609, issued by the Council of Ten, against illegal casini — gambling dens — is typical. Within it, we find (in my translation):

… the transgressors incur the penalty, if they are nobles, of banishment from the Maggior Consiglio for ten consecutive years …; if they are citizens of six years in a prison without light,3 or banishment from this city and district for the said period of ten years; and being of another condition, five years at the galleys, or ten years in prison, …

Mutinelli (1851), entry Casini.

While the law was applicable to everybody, the punishments were graduated by class. A nobleman breaking this law would only lose his political privileges, while a citizen would get a shorter sentence than a commoner, who alone could be sentenced to slave labour in the navy docks — the galleys.

Not only did members of different classes receive different punishments for the same transgressions, they were also sentenced by different courts.

Cases involving members of the nobility were heard in front of the Council of Ten.

The primary function of the Consiglio dei Dieci — the Council of Ten — was to safeguard the security of the state and the constitutional order. However, the state and the nobility were almost synonymous. Only the patricians participated in the political life of the state, and the state, therefore, became largely an expression of the collective interests of the nobility. Crimes committed by patricians, or crimes against patricians, consequently became a matter of state security and constitutional order, and therefore fell under the jurisdiction of the Council of Ten.

Crimes involving citizens were generally heard by a multitude of other institutions. Many of the first instance courts were collectively called the Corti di Palazzo — the Courts of the Palace. The Venetian state lacked the separation of powers which characterises modern states, and many state institutions had executive, legislative and judicial powers contemporaneously.

Separate courts heard cases involving persons from the Terra Ferma and other foreigners.

Mobility between classes

Possibilities of class mobility in ancient Venice were very rare — especially upwards.

The nobility and original citizenship were principally decided by place and status of birth.

The only notable exceptions were in those situations where the state desperately needed money — usually for warfare — and let some extremely wealthy, but not noble, families pay their way into the ruling elite.

It was possible for foreigners to become almost original citizens through the citizenship de intus et de extra.

The only fairly open class, the popolani or the citizens de intus tantum, was also the one with the least rights and privileges. However, Venice often needed skilled workers, so it made sense to leave that class more accessible.

Downwards mobility was far easier, if less attractive.

A criminal conviction could see a family drop out of the class of cittadini originari, for generations, if not forever.

A member of the nobility, or an original citizen, who married a popolana, lost their status as nobleman or cittadino originario. However, intermarriage between the nobility and the original citizens caused no loss of status. The nobility and the original citizens were both ‘real Venetians,’ as opposed to the lower classes.

One example of such a marriage is that of the daughter of Giovanni Dario into the Barbaro family. Giovanni Dario was a secretary of the Venetian Senate during the late 1400s, which was a position reserved for the cittadini originari. Consequently, his daughter Marietta was an original citizen. She inherited the Ca’ Dario on the Grand Canal after her father, and with her marriage to the nobleman Lorenzo Barbaro, the famous palace passed to Barbaro family.

This acceptance of close relations between the nobility and the cittadini originari also appears in the concept of ‘honest courtesans.’ Women like Veronica Franco and Angela dal Moro, both well-known prostitutes from the 1500s, were original citizens. As such, they could have amorous relationships with noblemen, without any loss of status or honour on either part. They were therefore honorate cortegiane.

This use of the word ‘honest’ is also one possible explanation of a rather odd place name in Venice — the Ponte and Fondamenta di Donna Onesta — which could, in fact, refer to a prostitute.

Notes

- Mutinelli (1851), p. 149, entry Ebrei. ↩︎

- The word Università does not mean an educational institution. The Università degli Ebrei had similar functions to a guild of artisans, in representing its members collectively and institutionally. There were other università for other groups, like the Università dei Povegliotti, which represented the displaced residents of Poveglia after the War of Chioggia in 1379-1381. ↩︎

- The “prison without light” — or prigione orba — were prison cells without any natural light. See Prigioni — Lessico Veneto. ↩︎

Related articles

- The Venetian state

- The Venetian Nobility

- State institutions of the Republic of Venice

- Prostitution in Venice

- Ca’ Dario

- Odd names in Venice – what were they thinking?

Bibliography

- Boerio, Giuseppe. Dizionario del dialetto veneziano. Venezia : coi tipi di Andrea Santini e figlio, 1829. [more] 🔗

- Da Mosto, Andrea. L'Archivio di Stato di Venezia : indice generale, storico, descrittivo ed analitico in Bibliothèque des Annales Institutorum, 5. Roma : Biblioteca d'arte, 1937. [more]

- Mutinelli, Fabio. Lessico veneto che contiene l'antica fraseologia volgare e forense … / compilato per agevolare la lettura della storia dell'antica Repubblica veneta e lo studio de'documenti a lei relativi. Venezia : co' tipi di Giambatista Andreola, 1851. [more] 🔗

- Tentori, Cristoforo. Saggio sulla storia civile, politica, ecclesiastica e sulla corografia e topografia degli Stati della Repubblica di Venezia ad uso della nobile e civile gioventù dell'ab. d. Cristoforo Tentori spagnuolo, 12 vols. In Venezia : appresso Giacomo Storti, 1785-1790.

Leave a Reply