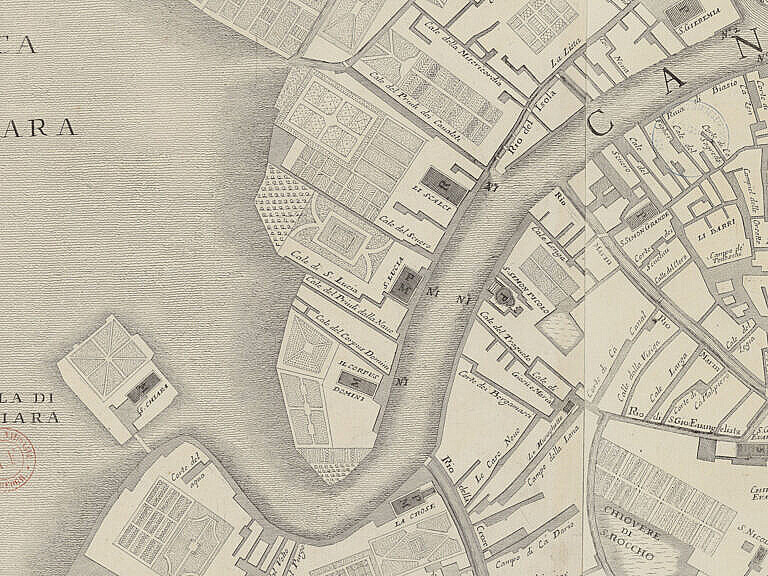

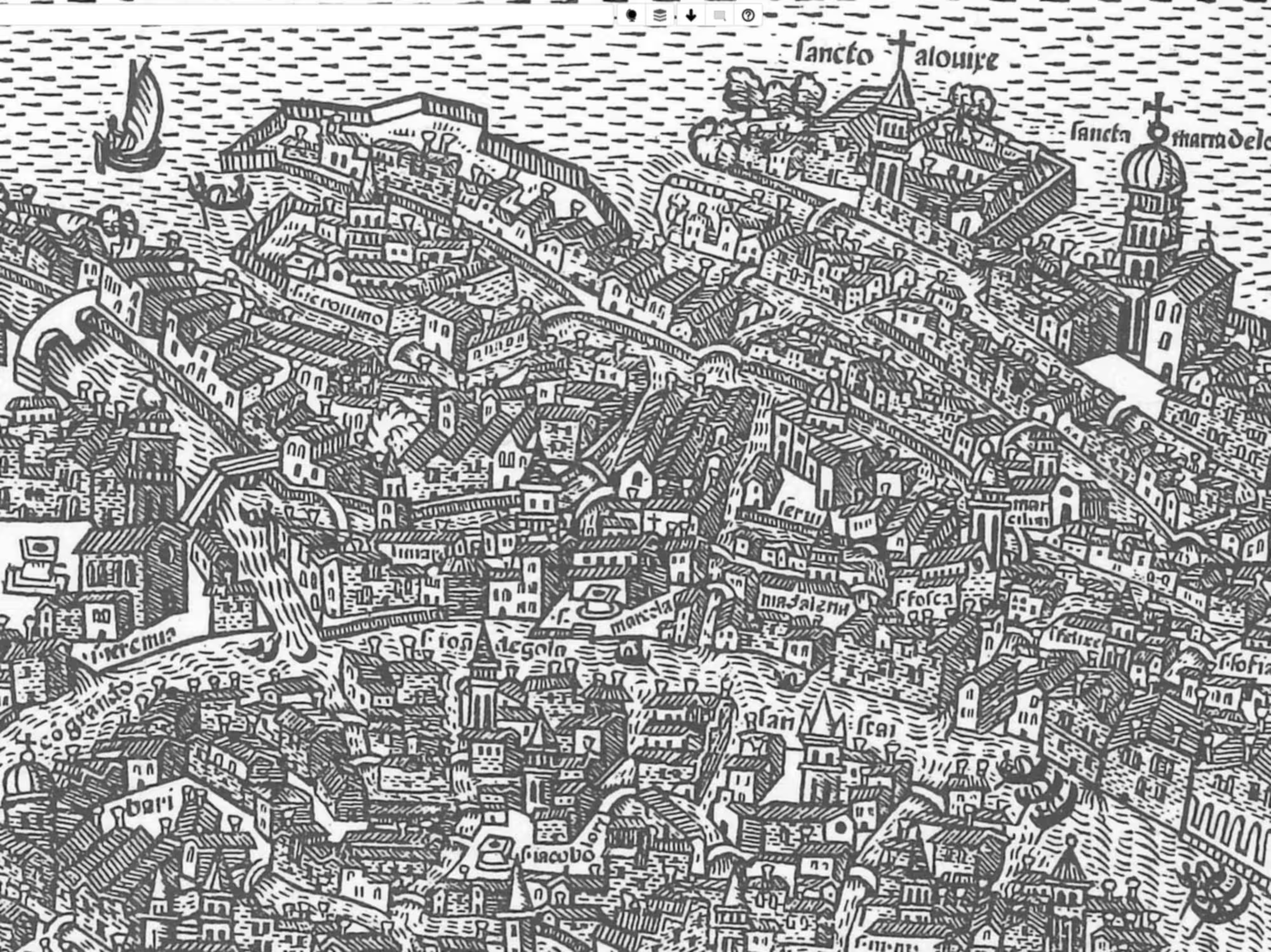

The area of the Santa Lucia railroad station is one of the most changed parts of Venice.

Strada Nova

This post is part of a series on the changes made to create the Strada Nova, which connects the railroad station with the Rialto area.

Very little would be recognisable to somebody from the early 1800s or before. To the west of the Scalzi church there is nothing left, absolutely nothing, of old Venice.

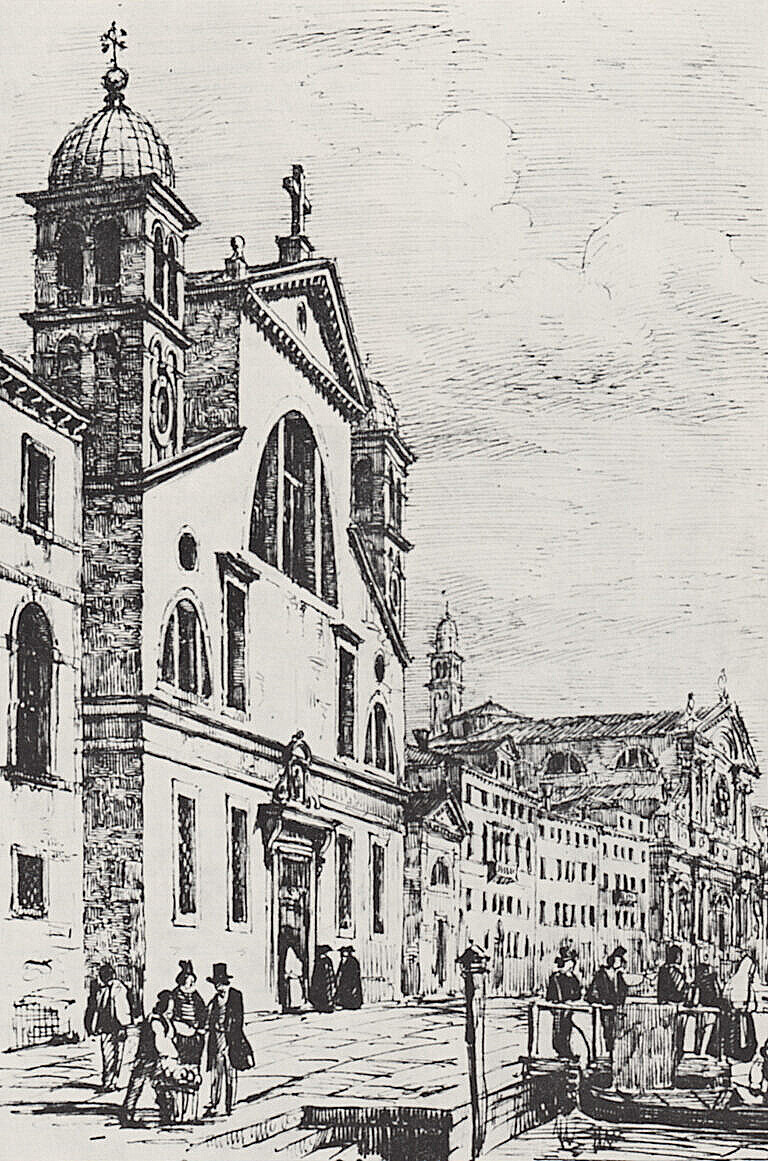

The painting below1 shows the Fondamenta di Santa Lucia as it once was.

From the left to the right, we have:

- the monastery of Corpus Domini;

- the church of Corpus Domini;

- private houses;

- the church of Santa Lucia;

- the associated school (a charity);

- more private houses;

- the church of the Scalzi;

- and finally the start of the Rio de l’isola.

Behind these buildings were the monastery of Santa Lucia, the monastery of the Scalzi, several gardens and orchards, some shipyards facing the lagoon behind, and many more private houses.

Only the Scalzi church and the associated monastery behind it still exist.

The church of Santa Lucia

The date of the foundation of the church of Santa Lucia is not clear. Some sources indicate the late 1100s, others 1192 as the Assunzione. What is certain is that the translation of the relics of St Lucy to the church happened in 1280. The dedication to Santa Lucia probably followed.

It underwent some restoration in the early 1300s because on August 3rd, 1343 three bishops re-consecrated it.

While it started as a parish church, in 1444 it passed under the control of the nuns of the nearby monastery of Corpus Domini.

Then in 1476 the church again passed to another group of nuns of the order of the Servi di Maria. The condition for the transfer was that they gave the relics of St Lucy to the nuns of Corpus Domini.

However, the latter nuns had a lapse of faith, and moved the relics to their church in the dead of night before the agreed date.

They then refused to return them, even when ordered so by the Council of Ten. To force the nuns to surrender the misappropriated relics, the Council of Ten first sent soldiers, but to no avail. The council then sent builders to brick up all the doors of the monastery until the nuns abided by the order given. In the face of starvation, the nuns surrendered the body of St Lucy, which returned to her own church.

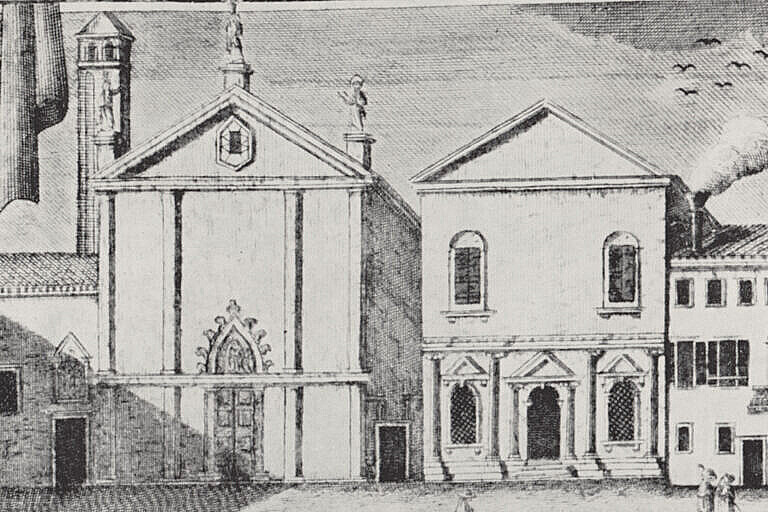

In the late 1500s, the church of Santa Lucia was in a sorry state. The Mocenigo family financed the restoration of the main chapel in 1565, on a design by Palladio. Later, other families paid for other chapels, and in the early 1600s the entire building received an overhaul. From 1611 onwards, it appeared as on the drawing above.

After the fall of the Republic of Venice, the monastery of Santa Lucia was suppressed in 1810 during the French domination. The church became an oratory associated with the church of San Geremia.

Corpus Domini

Abbess Lucia Tiepolo from Ammiana bought a plot of land near Santa Lucia in 1366, on what was then the extreme western end of Venice. Here she built a small wooden church and a monastery dedicated to Corpus Domini, where she and a few other nuns went to live.

Donations later permitted the reconstruction in stone of the monastery of Corpus Domini in 1393.

Apparently, the church sustained some damage in the early 1400s because it was rebuilt in 1440.

The monastery was exclusively for women from the aristocracy. The conflict mentioned earlier over the control of the relics of St Lucy might have been caused by a reluctance to cede such a precious object to other nuns of lower social extraction.

A confraternity of noblemen and wealthy merchants, the Scuola dei Nobili, had its building besides the church. The Scuola dei Nobili had a particular role in the annual Feast of Corpus Christi, which naturally centred on the Corpus Domini church.

The monastery was suppressed, like many others, in 1810 during the French domination.

The railroad

In the 1840s, the Austrians started building a railroad between Milan and Venice, the two main cities of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia under the Austrian Empire.

In 1846, the first bridge connecting Venice to the mainland arrived behind the church of Santa Lucia. However, the Venetian uprising against the Austrian domination in 1848-49 arrested the project for some time.

Finally, in 1860, the railroad was ready. The station had to be where the church of Santa Lucia stood. Consequently, the church and convent were demolished, and the relics of St Lucy were moved yet again, this time to the church of San Geremia.

The surviving buildings of Corpus Domini were demolished to make room for offices and administrative buildings for the railroads.

Now?

Now there is nothing left.

The only sign that the church of Santa Lucia ever existed is the name of the station, and a stone on the pavement where the church one stood, with an image of the church.

The site of the church and monastery of Corpus Domini is now an office building with a shopping mall on the ground floor.

Bibliography

Localities

Notes

- A part of The Grand Canal Facing Santa Croce by Bernardo Bellotto (based on a drawing by Canaletto), probably from the 1730s or 1740s, now in the National Gallery in London. ↩︎

This post is the first part of a series on the changes made to create the Strada Nova, which connects the railroad station with the Rialto area. The Strada Nova is arguably the beginning of mass tourism in Venice.

The following post covers the Rio del Isola and Lista di Spagna.

Curiosità Veneziane by Tassini has entries on Santa Lucia, Corpus Domini and the railroad station.

Leave a Reply