Slavery was not a large part of Venetian culture or Venetian history, but it was a part. There were slaves in Venice for the entire history of the Republic of Venice.

When people in some form of bonded servitude appear in the records — at least in the city of Venice — they were almost always domestic servants.

These are some of the testimonies about slavery in Venice I have found doing other research. In most cases, the stories come from criminal records, but not always.

Peter the Tartar (1324)

In the last will and testament of Marco Polo — dated January 9th 1323 m.v. — there’s this paragraph:

Also, I release Peter the Tartar, my servant, from all bondage, as completely as I pray God to release my own soul from all sin and guilt. And I also remit him whatever he may have gained by work at his own house; and over and above I bequeath him 100 lire of Venice denari.

Marco Polo kept a slave servant, and if Peter came to Venice with Marco Polo after his famous journeys, he would have lived in servitude for some thirty years.

The name Tartar could indicate Peter’s origin as in Crimea or somewhere in the Caucasus. It could also just be the Venetian using the word Tartar to indicate a slave from the Black Sea area, without any regard to his ethnicity.

Many slaves were baptised and given Venetian names, so the name Pietro was likely imposed on him by his enslavers.

Lucia (1360)

In a criminal case from 1360 about the fun-loving nuns of the monastery of San Lorenzo, we find this:

Shortly afterwards, that is, on 22 July 1360, Margarita revendigola,1 Bertuccia widow of Paolo d’Ancona, Maddalena da Bologna, Margarita da Padova, and Lucia, a slave, were publicly whipped for having brought, in modum ruffianarum, letters and amorous embassies to those nuns.

Tassini (1863), entry San Lorenzo.

One might suspect that Lucia, given her status, had little say in whether she wanted to carry love-letters to and from the nuns, but she got flogged anyway.

Giovanni (1370)

Giovanni was a slave to Domenico Gaffaro, parish priest of San Basso in Venice, then of San Nicolò on the Lido, and finally bishop of Eraclea.

At night, Giovanni stabbed his master in the throat and robbed him, aided by his brother Pietro, also a slave, and a woman Catterina, also a slave. They were caught, and cruelly punished, in particular Giovanni:

He shall be taken by boat up to S. Croce,2 while a herald continuously shouts his crime, then by land to the bishop’s house, where his right hand is cut off, and with it hanging around his neck he shall be led to the Rialto, and there flesh shall be cut in four places, from cheeks and arms; he is then dragged back to San Marco, and flesh shall be removed from his thighs and chest, in four places; he shall then be killed, quartered, and the quarters hung on two gibbets between the two columns until the end of Sunday, then on the usual gibbets where they shall remain continuously.3

Cecchetti (1886).

Pietro was executed and quartered, after having seen the torment of his brother, while Catterina was branded, had her nose cut off, and exiled.

It is probable that the bishop died of his wounds, as the raspe (the criminal records) described the attack as cum periculo vitae, and four years later somebody else appeared in the records as bishop of Eraclea (Tassini (1866), chapter VIII).

Bona Tartara (1410)

The story of Bona Tartara is just as sinister.4

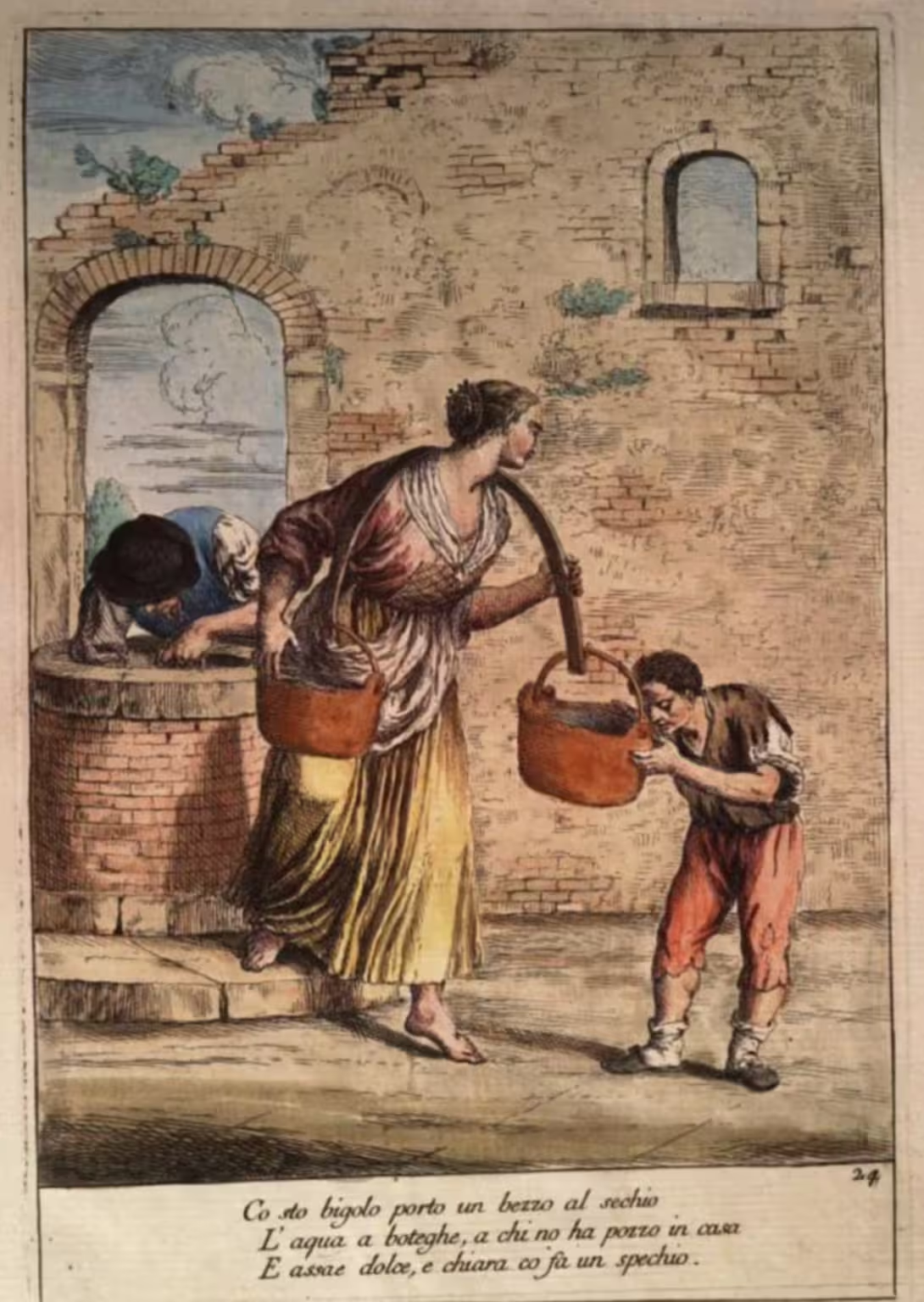

Bona was a slave to Nicolò Barbo at San Pantaleon. When she remained pregnant with one of his other servants, he beat her badly with a bigolo — a yoke — for carrying water.

For revenge, she went to a pharmacy, bought some arsenic and put it in his soup. He died shortly after.

The Quarantia al criminal sentenced her to be taken by boat down the Grand Canal, tied to a post while a herald loudly announced her crime, then to be dragged tied to the tail of a horse back to San Marco, where she was executed and her body burned between the two columns.

Law against party nuns (1486)

In 1486, the Venetian senate passed a law against immorality in monasteries, especially fornication with nuns.

As always, Venetian law enforcement relied on informants. The laws therefore often contained various incentives to get potential informants to come forward.

In this law about preventing men from entering nunneries for illicit activities, we have:

And if in the said monasteries there were female slaves, and they made such an accusation and if they told the truth, beyond what was granted to them above of half of the fine, they also remain free from that mistress of theirs …

Mutinelli (1851), entry Monachini, Moneghini.

If nuns could have slave servants, the people of the time hardly saw any serious moral or ethical issues with slavery.

Female slave (1540)

Tassini, in his Curiosità Veneziane, copied this from an unpublished manuscript in the Museo Correr

On the day 26 August 1540, at the hour 15, during the day, a fire started in the district of Santa Maria Nova in the houses behind the said church, where Bernardin Gusmazi was parish priest … The fire started by means of some sparks, and was so fast as to not let anything escape. The fire was made by the hand of a young female servant, a slave, who because beaten by her master, did this, and fled, and there was great damage to the priest.

The Barbo chronicle, Biblioteca del Museo Correr, Cicogna 2279, here from Tassini (1863), entry S. Maria Nova.

Recapitulating, the priest had a female slave, which he mistreated. As revenge, she made the fireplace burn too hot and caused a major fire, which cost the priest a lot of money.

Slaves in Venetian art

Every once in a while, slaves (or probable slaves) appear in artworks.

Here are a few examples.

The Miracolo del Santo Croce a Rialto (1494) — the Miracle of the Holy Cross at the Rialto — by Vittore Carpaccio.

The main religious event of the painting is relegated to the upper left side, while the Grand Canal below is full of rowed boats.

One of the rowers is a black man, probably a slave.

The Miracolo della Croce caduta nel canale di San Lorenzo (1500) — the Miracle of the Cross fallen in the canal at San Lorenzo — by Gentile Bellini.

A sacred cross had fallen in the water and everybody tried to recover it. On the extreme right side, a black man in a loincloth, standing on some steps, is also looking for it.

Furniture by Andrea Brustolon, c. 1700–1706, made for Venetian nobleman Pietro Venier.

A Baroque piece of furniture made as a support for a collection of Chinese vases, which depicts three moors in chains.

Notes

- A rivendigola was a collector of used clothing for resale. ↩︎

- From San Marco to Santa Croce was the entire length of the Grand Canal. ↩︎

- The usual gibbets were in the lagoon, along the main canals leading to the city — see The mysterious hooks of fortune at San Canciano. ↩︎

- This case is covered in Tassini (1866), chapter XV. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Cecchetti, Bartolomeo. La donna nel medioevo a Venezia in Archivio Veneto, Anno XVI, Tomo XXXI, Parte I e II. Venezia, Stabilimento Tip. Fratelli Visentini — editori, 1886.

- Mutinelli, Fabio. Lessico veneto che contiene l'antica fraseologia volgare e forense … / compilato per agevolare la lettura della storia dell'antica Repubblica veneta e lo studio de'documenti a lei relativi. Venezia : co' tipi di Giambatista Andreola, 1851. [more] 🔗

- Tassini, Giuseppe. Curiosità Veneziane ovvero Origini delle denominazioni stradali di Venezia. 1863. [more] 🔗

- Tassini, Giuseppe. Alcune delle più clamorose condanne capitali eseguite in Venezia sotto la Repubblica: memorie patrie. Edited by Giuseppe Tassini, 1866. [more] 🔗

Localities

Related articles

- Fornicators of Nuns

- The testament of Marco Polo

- Porta Bigolo con acqua — water bearer — Zompini — Arti #24

- The mysterious hooks of fortune at San Canciano

Leave a Reply