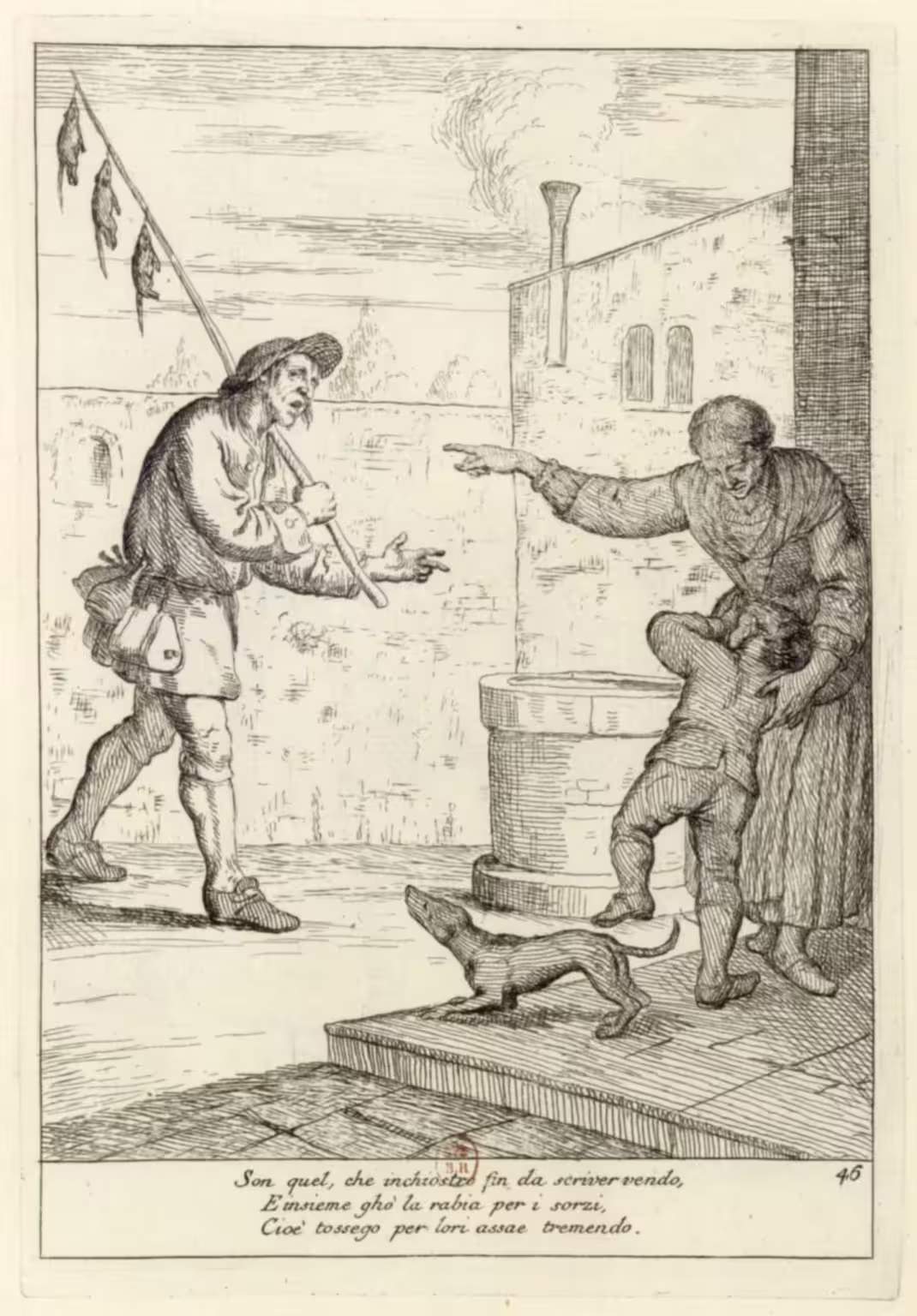

In the Arti che vanno per via in Venezia (1753) by Gaetano Zompini, one of the trades depicted is a man with a long stick with dead rats attached, and also a series of bottles or jugs in his belt.

The associated poem says (in my translation):

I’m the one who sells fine ink for writing,

And I also have the stuff for rats,

That is, a very terrible poison for them.

The man is thus selling both writing ink and rat poison. The containers on his belt are conceivably for the ink and/or rat poison.

That struck me as a rather odd combination of goods for a street vendor. Why would the same person sell writing ink and rat poison?

Wait, there’s more …

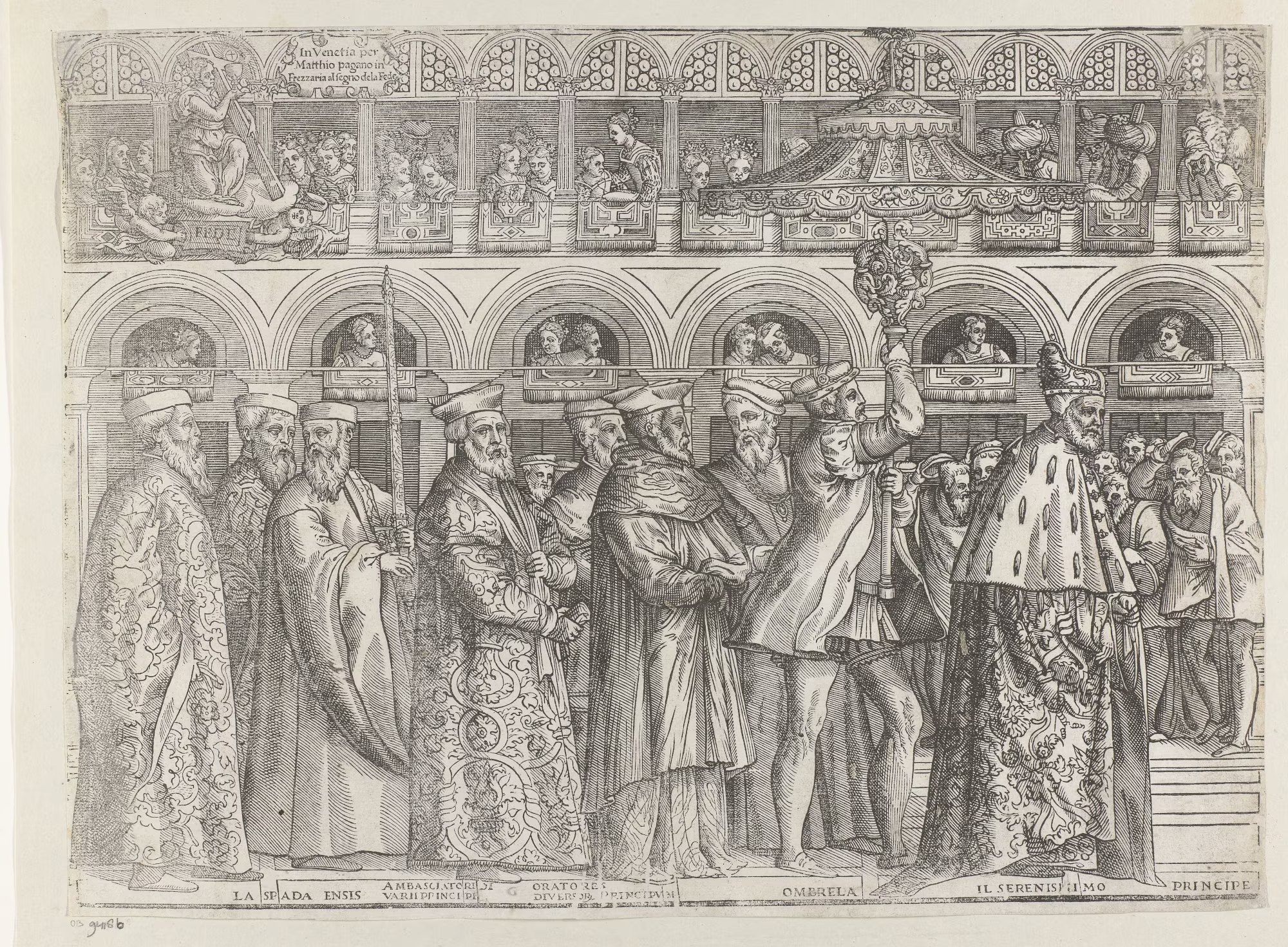

Another work from the same period, the Gli Abiti de Veneziani (1754) by Giovanni Grevembroch, has a very similar figure.

The person in Grevembroch’s depiction also carries dead rats on a long stick as proof of the effectiveness of the poison on sale. He has a small barrel on his back, presumably some liquid, and carries a basket with some small packages.

The text associated with Grevembroch’s watercolour only mentions rats, but the dedication of the illustration is to “the Jew Moise Levantino, Fabricator of Ink and Sealing Wax, sold industriously throughout the City.”

Here too, albeit indirectly, we have the connection between writing ink and rat poison.

Arsenic

The most common poison — which was also used for rats — was arsenic. Arsenic is a natural occurring substance, which was well-known in the past.

In the criminal records of the Republic of Venice, there’s the story of the slave woman Bona Tartara. Her owner beat her severely with a yoke, after which she poisoned him by putting arsenic in his soup.

Arsenic, however, was not sold on the streets by vagrant vendors, not even in 1410. It is much too dangerous for that. Bona Tartara had to go to a pharmacy to get it.

It is therefore unlikely that the street vendors depicted by Zompini and Grevembroch in the mid-1700s sold arsenic. A poison that potent was only sold through licenced pharmacies.

Add to this that arsenic plays no role in the production of writing ink. There is no connection, so it probably wouldn’t answer our question.

Iron Gall Ink

The most common form of writing ink was iron gall ink, so this was likely the kind of ink the street vendors were peddling.

Iron gall ink is made by galls, which grow on oaks when the tree reacts to the eggs and larvae of wasps. Galls are rich in tannic acid.

An extract from the galls is mixed with ferrous sulfate to produce a blackish and very durable ink. Gum arabic is added as a binder, to make the ink stick to both quill and paper.

This process was well-known even in the early Middle Ages.

The only substance in the recipe for iron gall ink with any kind of toxicity is the iron.

Iron overload

Iron poisoning — or iron overload — happens when the body absorbs too much iron. It can cause damage to the liver, the heart and other organs. In extreme cases, it can be fatal.

According to Wikipedia, a dose of 120mg of elementary iron per kg of body weight can cause death.

An adult rat weights around half a kg, so a dose of as small as 60mg iron would kill or incapacitate a rat.

The ferrous sulfate, used for the production of iron gall ink, contains about one third elementary iron. Consequently, it’ll take less than 200mg of ferrous sulfate to kill a rat.

Hiding one fifth of a gram of in some bait for the rats could hardly be an issue.

A hypothesis

Many of the street vendors depicted by Zompini and Grevembroch sold combinations of goods, which we might find odd. The reason is, most often, that the people came from areas outside of Venice, and sold whatever their place of origin produced.

Therefore, confronted with a figure selling both rat poison and writing ink, it is natural to assume that the two products somehow had a common source.

If the rat poison sold by these street vendors was based on ferrous sulfate, it would make sense that the same person sold both products. He would get his supplies from the same source.

The much lower toxicity of ferrous sulfate meant that it could be sold on the streets, rather than through the licenced pharmacies. In the quantities necessary for rats, it is innocuous to humans.

This is, however, only a hypothesis, as I haven’t been able to find any documents from the time clearly stating the connection.

Related articles

- Inchiostro — vendor of ink and rat poison — Zompini — Arti #46

- Predatori Predati — Grevembroch vol. 4, plate 86

External links

- Iron Gall Ink — by Sara Charles of the University of London

Leave a Reply