In Venice, every stone tells a story. While this is an old trope, it is still true.

I was walking my dog in the morning, during the recent lockdown, and sat down for a minute on a low wall between the Giardini Pubblici in the Sestiere Castello and the nearby canal.

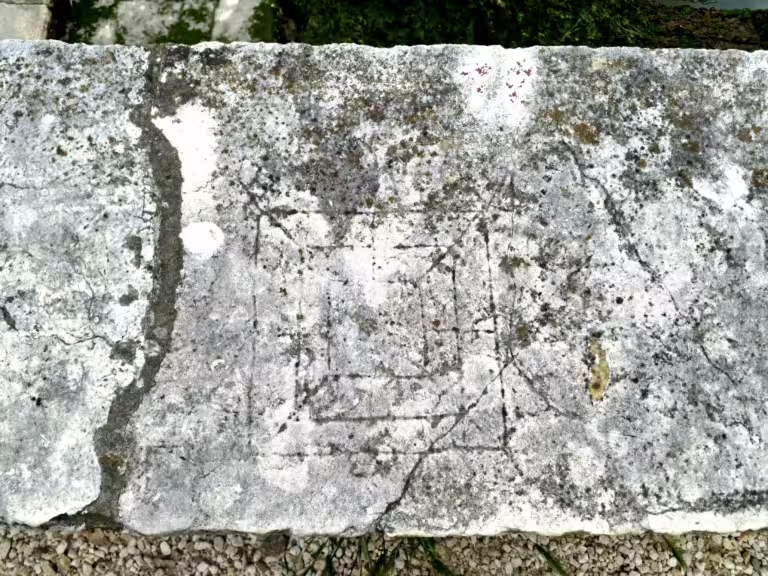

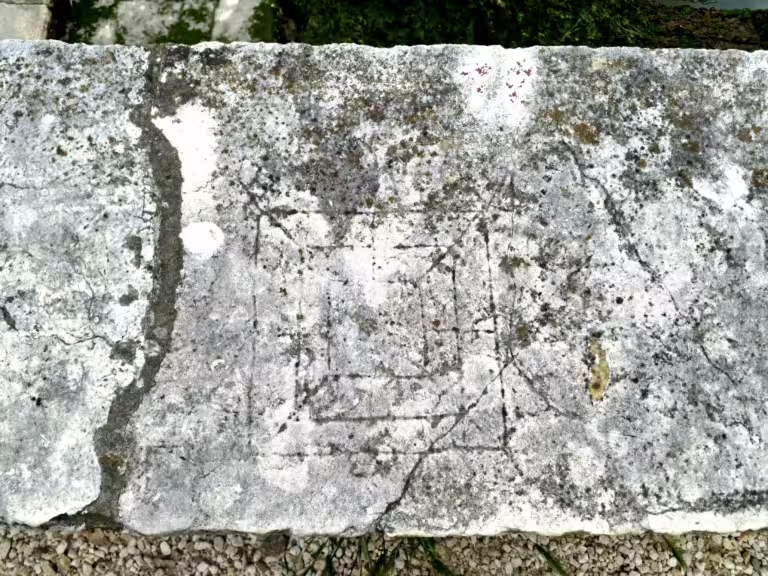

In front of me, incised on an old slab of pietra d’Istria, was a game board.

The game was easily recognisable, because I played that game as a child. It’s called “Nine men’s Morris” in English, but in most other languages the name is a variation of the word “mill”.

Nine men’s Morris is an ancient game, going back millennia. Similar boards have been found incised on ancient Greek temples, Roman buildings and on artefacts from the Viking age.

So, how old will the board in the Giardini in Venice be?

Alas, we have no way of knowing. It could be centuries old, and it could be far more recent.

The wall, the stone forms a part of, is no older than the start of the 19th century.

That was when the Giardini as we know it, were made.

Before that, the area was totally different.

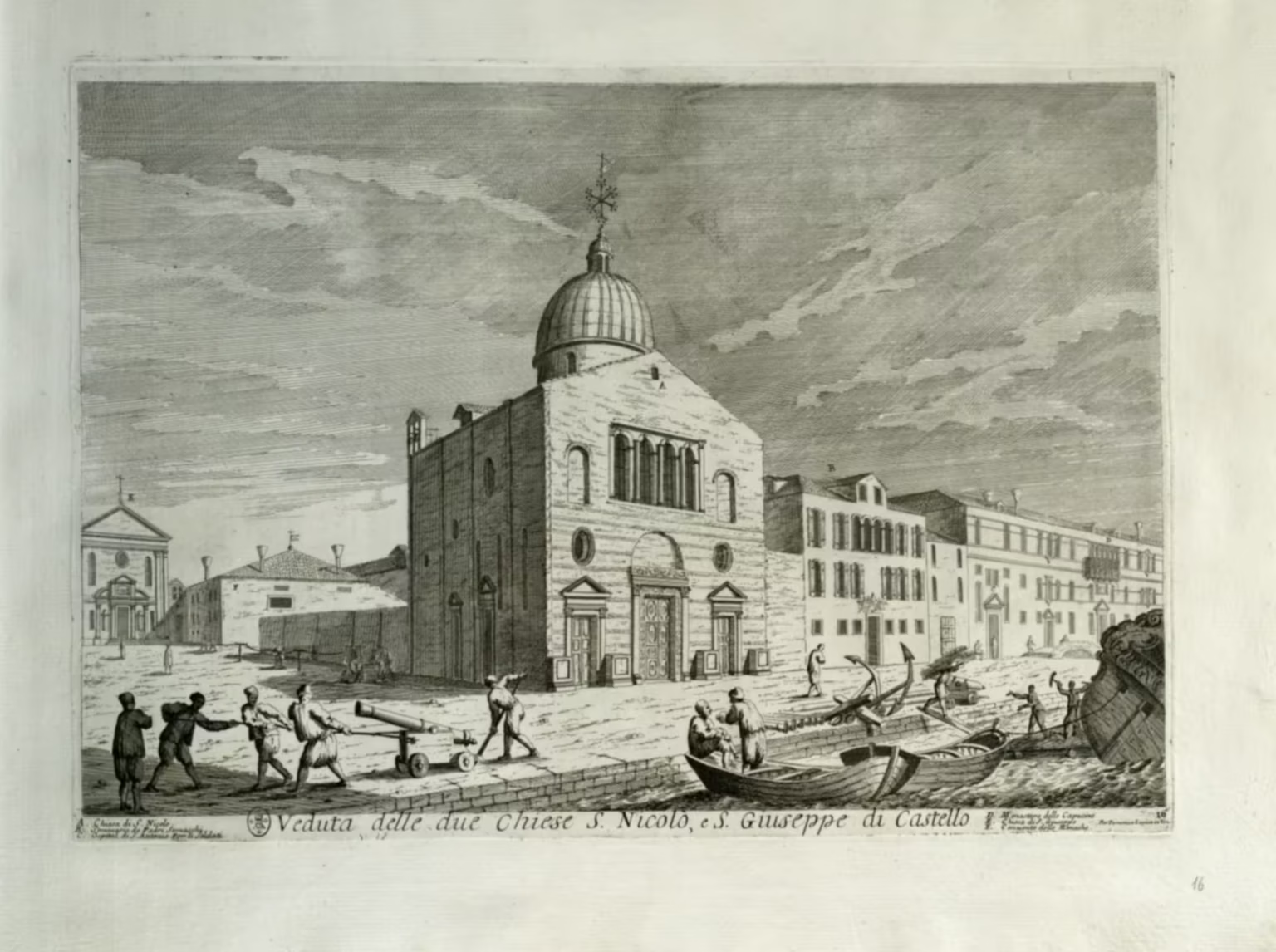

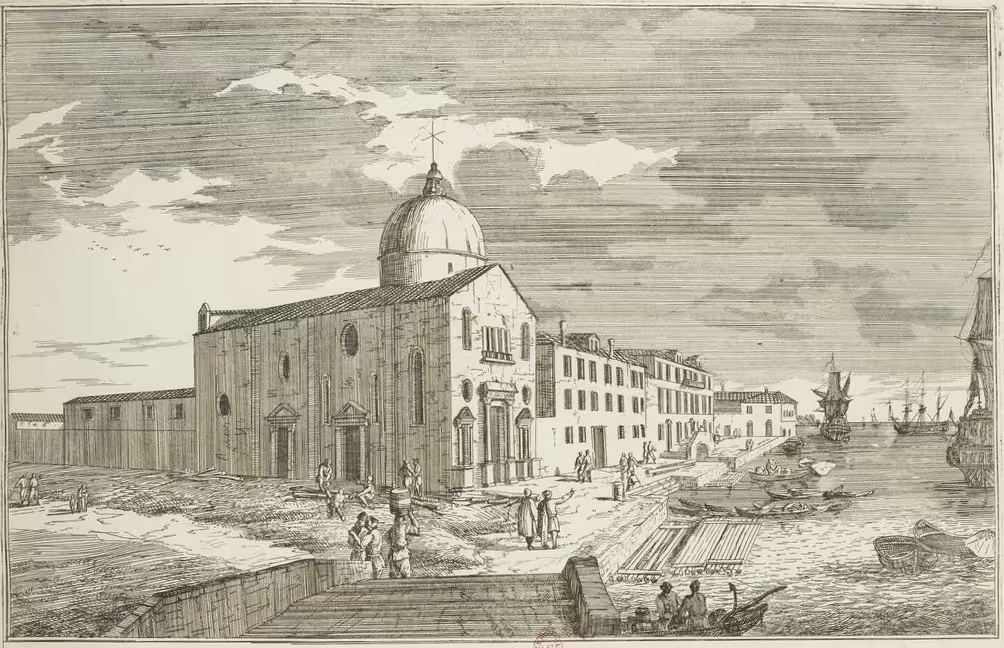

Where the wall and the nearby arch now stand, there was an open square along the canal, stretching from the open water to the church of San Giuseppe.

San Nicolò di Castello

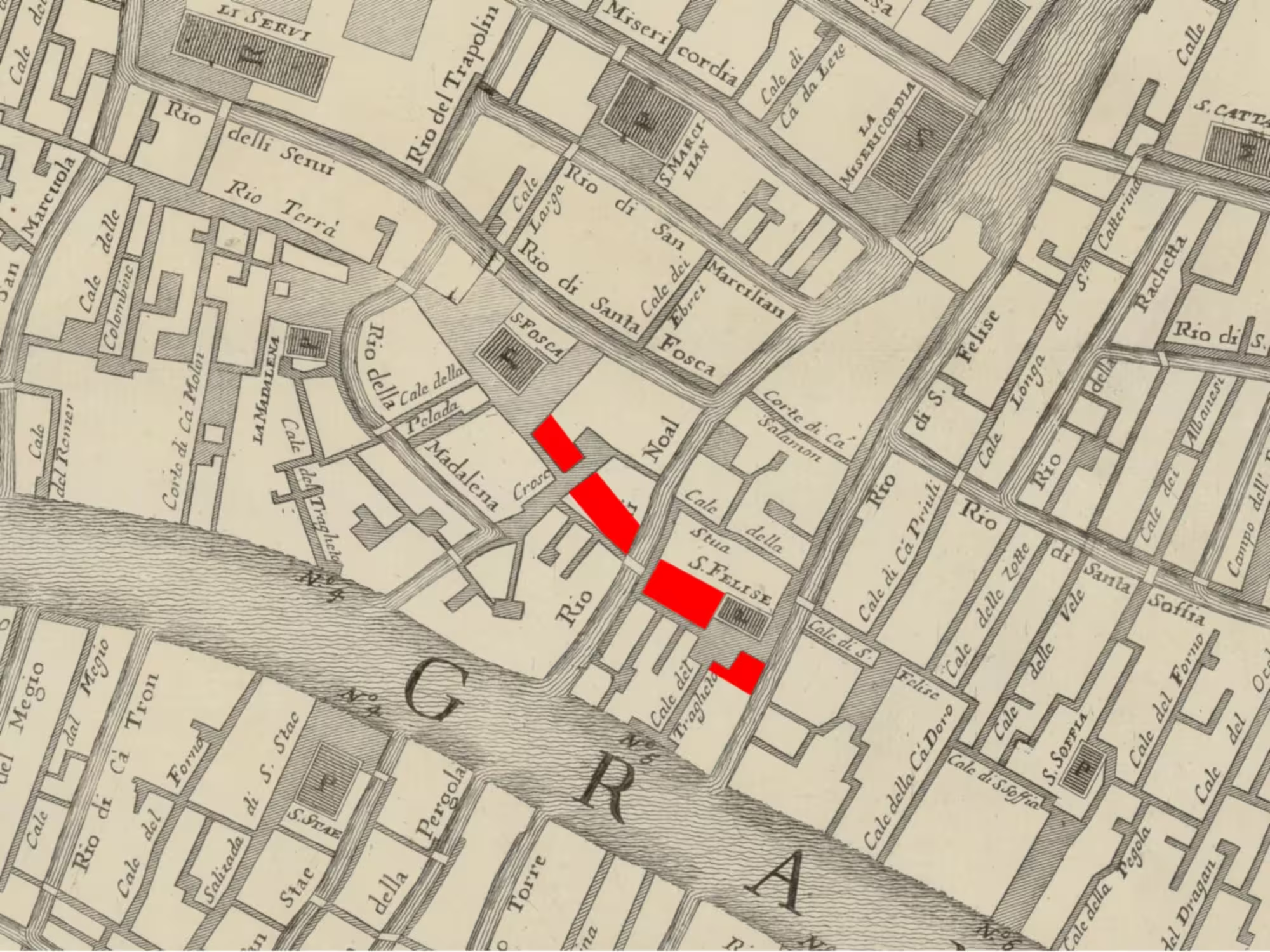

A bit away from the canal was the church of San Nicolò di Castello, dedicated to St Nicholas, and the mariner’s hospital.

Further away from the canal stood the church of Sant’Antonio Abate, one of the largest churches in Venice. It contained chapels and burials for many of the great noble families of the Serenissima.

The two churches and the hospital were all demolished on their order of Napoleon after the fall of the Venetian Republic, to make room for the public gardens and the area now occupied by the Biennale.

The new rulers no doubt sold off the best of the building materials from the churches, but much remained behind. The alert visitor will notice stones clearly recycled from old buildings scattered around the Giardini.

The stone slabs on the low wall along the canal most likely came from the nearby church, and perhaps the game board was once inside the church.

As is often the case with such inconspicuous bits of the past, we’ll never know. We can guess, dream, fantasize, but it is unlikely we’ll get any further.

Related articles

- Long live the doge

- Runes in Venice

- The mysterious hooks of fortune at San Canciano

- The Fall of Venice

Leave a Reply