In 1708 King Frederick IV of Denmark and Norway, then travelling in Italy, communicated through his ambassador in Venice his desire to visit the city. The Venetian government had few material interests in such a visit, as Denmark and Norway were rather distant, but he was a royal and a head of state.1

The Serenissima therefore sent a formal invitation to the king. Frederick IV accepted the invitation, but explicitly as Count of Oldenburg, not as King of Denmark and Norway.

Why would he come to Venice as a count, but not as a king? He wanted to participate in the famous Venetian carnival, and was afraid that a formal state visit wouldn’t allow him that pleasure.

The origins of the Venetian carnival

A carnival is not a unique Venetian thing. There were and are carnivals all over Europe and elsewhere.

It has pre-Christian roots, such as the Roman Saturnalia, and there’s a Christian part, connected to the penances of Lent.

For most of Lent meat and dairy were banned or very limited, so in the period just before people went overboard with all the food and drink they knew they couldn’t have until Easter. The word “carnival” means, in some form or another, farewell to meat.

The ancient Roman connection is more in the form the festivities took, by wearing masks and disguises. Venetian society, like most societies of the past, had a high level of social and economic inequality, which inevitably created social tensions. By dressing up and hiding one’s identity, or even by having masters and servants swap roles for a day or two, some of those inequalities were lessened.

As such, feasts like the Roman Saturnalia and the later carnivals became safety valves for social tension.

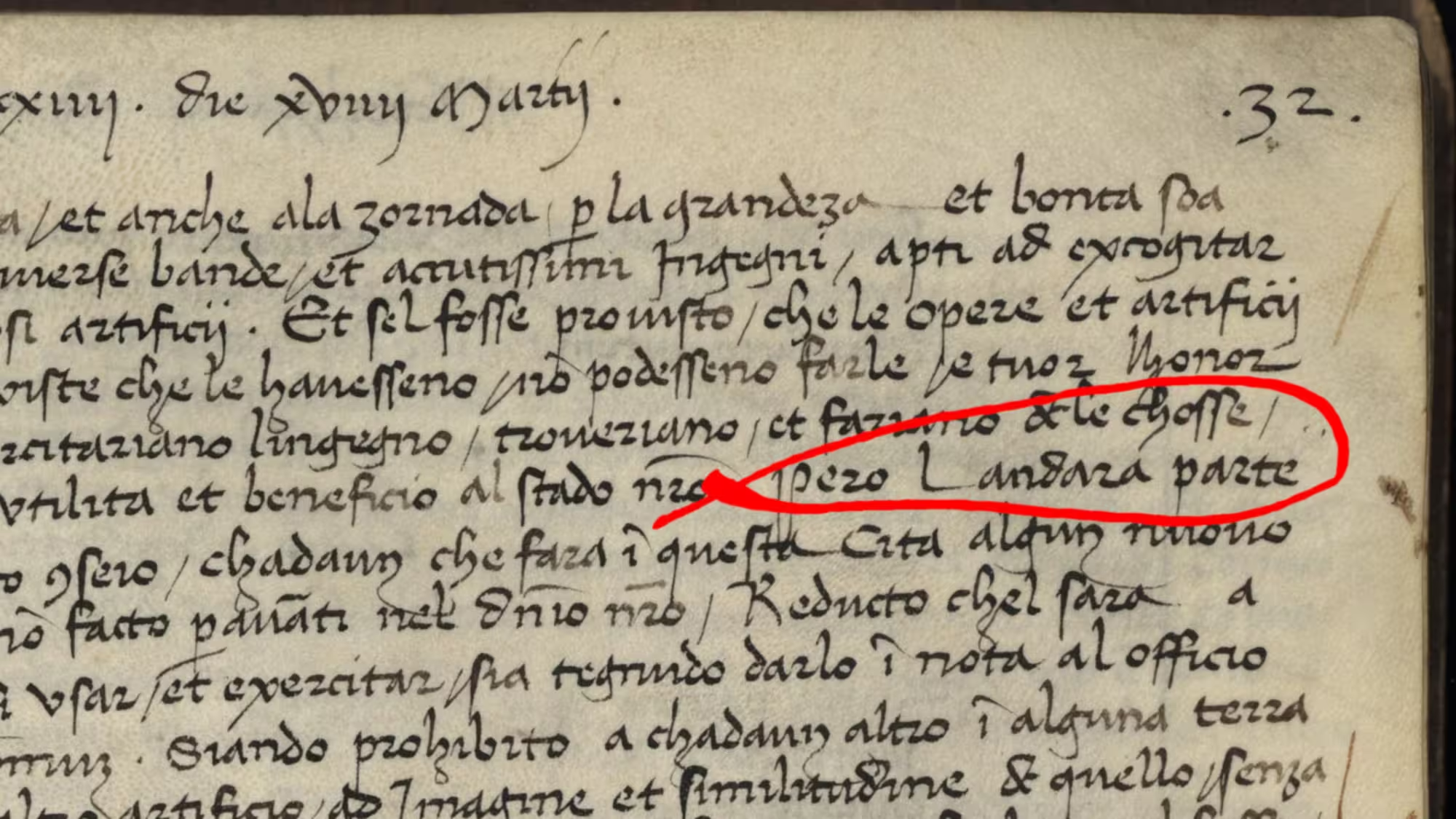

And the origins are ancient. Venetian documents from the 1000s mention the carnival by that word, and it appears in official documents from the 1200s. It soon became a fixture in Venetian social life.

When Frederick IV of Denmark and Norway arrived in Venice in 1708, the Venetian carnival was a major event for centuries.

Masks and figures

Over the centuries, different kinds of carnival figures developed.

The most popular figure was the bauta. The bauta wore a traditional long Venetian black cloak, called a tabarro, a tricorne hat and a simple mask called a larva.

The mask looks almost square, seen from the front, but it has a large beak-like protrusion in front of the mouth. This design served a double purpose. It distorted the voice, thus adding to the disguise and anonymity, and it still allowed the bearing to eat and drink.

This practical aspect might be part of the reason for the figure’s popularity. Both men and women could be a bauta.

The bauta was the only disguised figure allowed outside the carnival season.

A strictly female carnival figure was the moretta. The mask was a dark piece of velvet, held in place over the face by a string around the neck, and by a button held in the mouth.

The moretta was therefore a silent and passive figure, hence also called servetta muta — silent little maid.

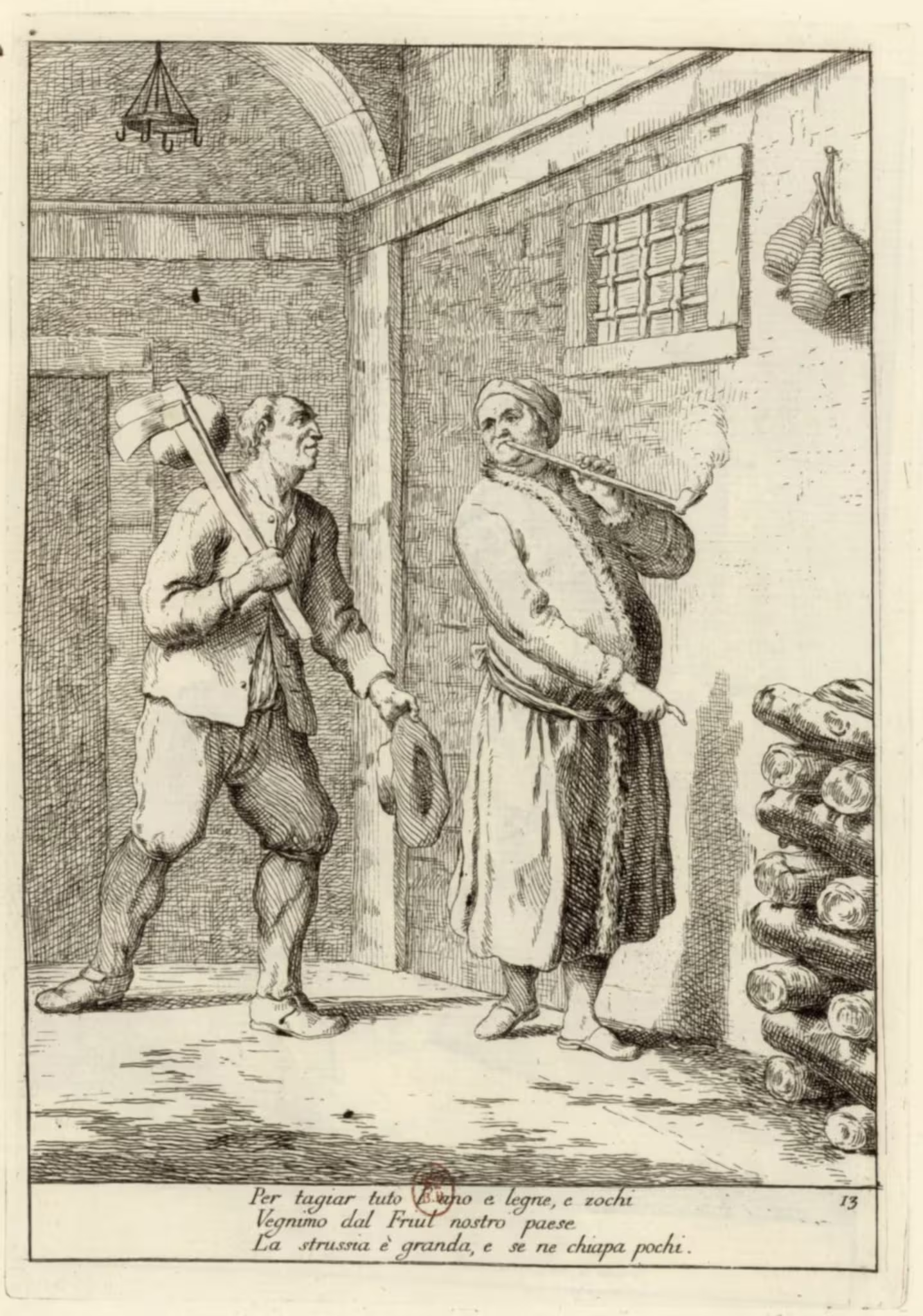

Another, maybe surprising, figure was the gnaga. It was a female figure for men. They would cross dress in simple woman’s clothes, and wear a cat-faced mask. Often they would also carry a basket on their arm with a live kitten. The figure wouldn’t speak, but rather squeak and meow. All in all, a caricature of a lower-class woman.

There were many other common figures, often mimicking lower-class people in a mocking way.

Many women would wear a simple full face mask with a feminine appearance, with a fine dress and a tricorne hat, as in the painting at the top of this page.

Social and public order

The Venetian carnival started just after Christmas, on December 26th, and continued for six weeks until Lent. Clearly, the ancient Venetians subscribed to the adage that if something was worth doing, it was worth doing well.

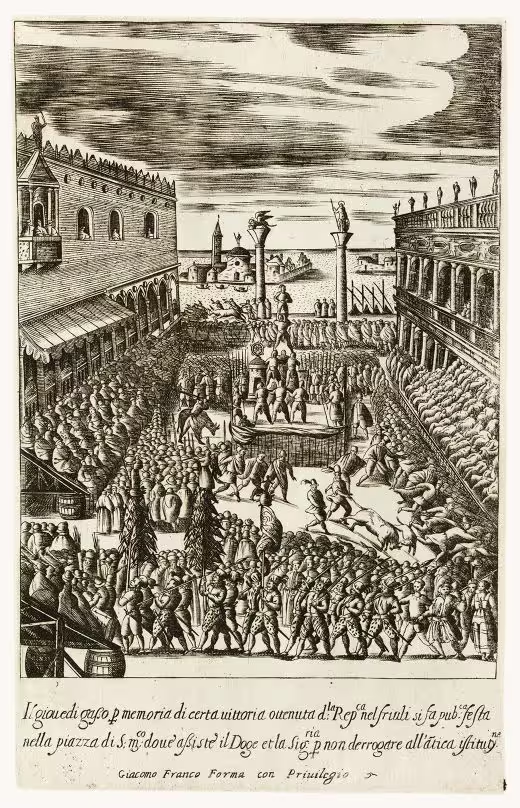

Six weeks of fancy balls, fine dinners and exotic entertainment for those with sufficient money. For the common people, street parties, competitions like the Forze di Ercole (human towers), and bull fights in public squares.

However, with numerous people roaming the city in disguise, day and night, there was room for a lot of wrong-doing, of all sorts.

Burglars, robbers and all sorts of criminals were free to act during the carnival if people wearing masked abounded. The common use of long cloaks allowed people to hide weapons and whatnot underneath. People gambling could use the disguise to avoid paying their debts, while others might use the masks to sneak into a nunnery for a bit of fun.

As all sorts of vice therefore flourished during the carnival, the authorities often had to intervene with bans and sanctions to keep order. On the other hand, the problem of criminals masking was specific to the carnival, as the stories around the Ponte dei Assassini — the Assassins’ Bridge — tell us.

Masking wasn’t exclusively for the carnival. It was also a way of gaining privacy. When going to a brothel, to a casino or simply to meet others for private affairs, being able to move anonymously had its use for the upper classes.

The ban on wearing masks outside the period of the carnival therefore excluded the bauta. That dress and mask could be worn all year.

The modern carnival

The carnival presented a problem for the new alternating Austrian and French rulers after the fall of the Republic of Venice in 1797. It created too many possibilities for the Venetians to act anonymously. Even if not formally forbidden, it was not encouraged.

Soon the custom died out, and the carnival in Venice became a thing of the past.

In the 1970s, some Venetians picked up the ancient tradition, and organised a grassroots carnival. Children and adults alike dressed up and had fun.

Gradually, like it happens with almost everything successful in Venice, such events are taken over by the tourist industry. By now, there’s almost no participation by the residents of the city, which are also fewer every year.

For some of the major events in the ten-day carnival period, the locals can find themselves excluded from the streets they live in, if that are occupied by the event. Those who can often flee the city for the carnival period.

The Venetian carnival is no longer for the Venetians.

Notes

- This version of the story is taken from Giustina Renier Michiel, Origine delle feste veneziane, Milano, 1817-29. ↩︎

Related articles

- An earl, a girl and a gondola

- An Englishman in Venice — the diary of John Evelyn — 1645

- Clara — the star of the Carnival

Leave a Reply