In the spring or summer of 1214, or maybe 1215, the good people of Treviso held a huge celebration, which lasted several days.

Venetian Stories

This post is an issue of our newsletter — Venetian Stories — which goes out every few weeks, to keep in touch and share stories and titbits from and about Venice and its history.

Imagine a medieval festival, with trumpeters and banners, armoured knights jousting, ladies in expensive dresses of silk and brocade, grand balls in the evenings, and endless dinners.

Our sources don’t all agree on the reason for the festivities, but invitations went out to neighbouring cities far and wide, including Padua and Venice.

Noblemen and women came to Treviso in their thousands, for a week of fun, jousting, games and parties. Everybody dressed in their finest because this was a chance to show off for the entire region.

In the 1200s, all these cities were still more or less independent small states, so it was an international event.

In love and war …

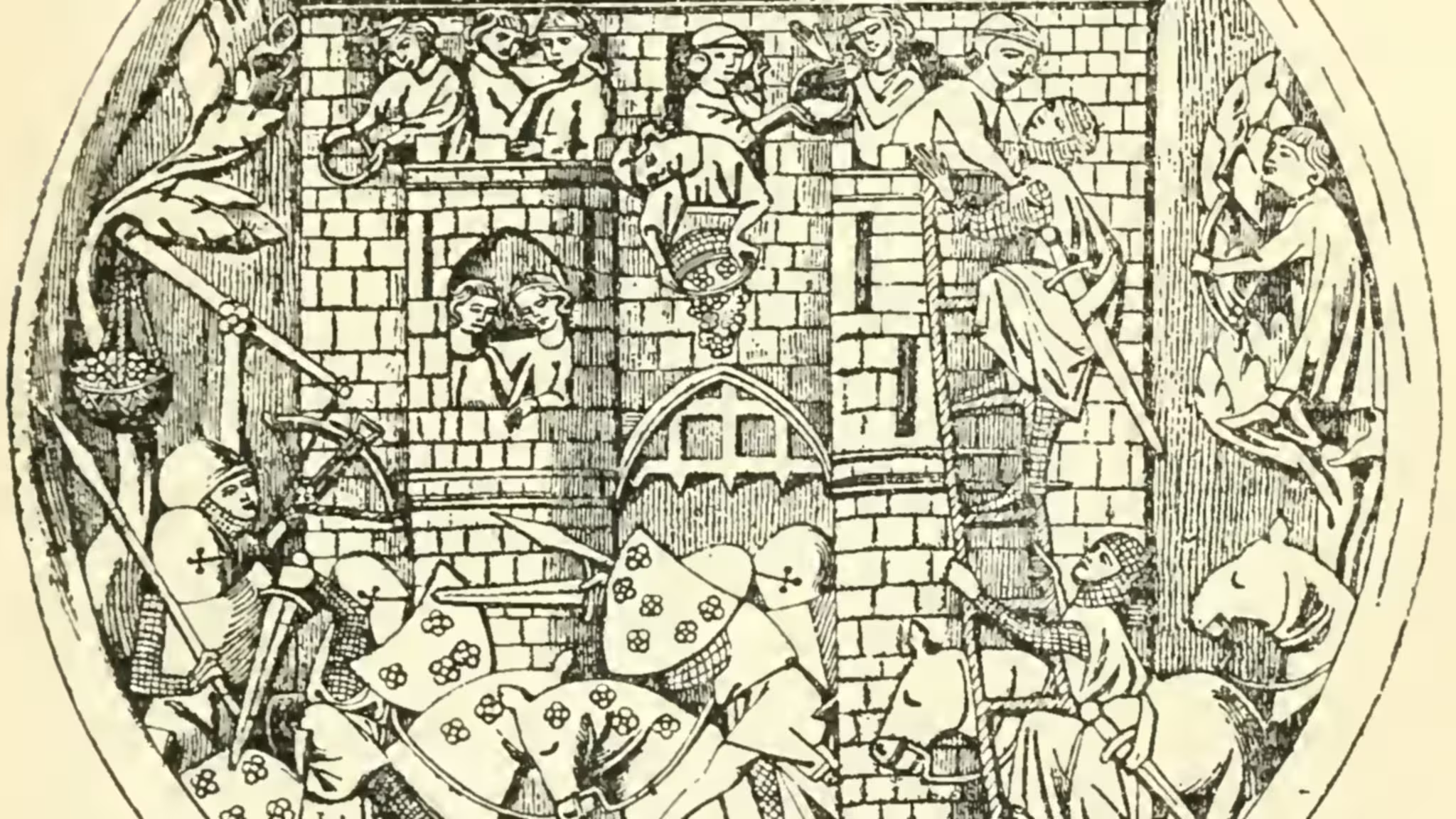

One of the games was a Castle of Love.

The game of Castle of Love is known from later romantic troubadour literature, but it must have been around for a while, as this event is about a century earlier than most literary mentions.

Here is a contemporary description of the event, by Rolandino da Padova (1200–1276):

In the year 1214 Albizzo da Fiore was Podesta of Padua, a prudent and discreet man, courteous, gentle, and kindly ; who, though in his government he was wise, lordly, and astute, yet loved mirth and solace.

In the days of his office they ordained at Treviso a Court of Solace and Mirth, whereunto many of Padua were called, both knights and footmen. Moreover, some dozen of the noblest and fairest ladies, and the fittest for such mirth that could be found in Padua, went by invitation to grace that Court.

Now the Court, or festivity, was thus ordered. A fantastic castle was built and garrisoned with dames and damsels and their waitingwomen, who without help of man defended it with all possible prudence.

Now this castle was fortified on all sides with skins of vair and sable, sendals, purple cloths, samites, precious tissues, scarlet, brocade of Bagdad, and ermine. What shall I say of the golden coronets studded with chrysolites and jacinths, topaz and emeralds, pearls and pointed headgear, and all manner of adornments wherewith the ladies defended their heads from the assaults of the beleaguerers ?

For the castle itself must be assaulted ; and the arms and engines wherewith men fought against it were apples and dates and muscat-nuts, tarts and pears and quinces, roses and lilies and violets, and vases of balsam or ambergris or rosewater, amber, camphor, cardamums, cinnamon, cloves, pomegranates, and all manner of flowers or spices that are fragrant to smell or fair to see.

I suppose using traditional siege tactics, and simply starving the women out, would have been detrimental to the fun.

Besides the way love and war are woven together in this game, it is also an incredible display of wealth and opulence.

They practically had a massive food fight using the equivalent of caviar, truffles and foie gras.

The enemy arrives …

Rolandino da Padova continues:

Moreover, many men came from Venice to this festival, and many ladies to pay honour to that Court ; and these Venetians, bearing the fair banner of St. Mark, fought with much skill and delight.

Yet much evil may spring sometimes from good beginnings ; for, while the Venetians strove in sport with the Paduans, contending who should first press into the castle gate, then discord arose on either side ; and (would that it had never been !) a certain unwise Venetian who bare the banner of St. Mark made an assault upon the Paduans with fierce and wrathful mien ; which when the Paduans saw, some of them waxed wroth in turn and laid violent hands on that banner, wherefrom they tore a certain portion ; which again provoked the Venetians to sore wrath and indignation.

The rivalry between Venice and Padua was ancient.

Each city was the capital of an independent duchy, but Padua was much older than Venice. It already existed in Roman times, while Venice was the up-start.

However, Venice was very much on the ascendency at this time. The close association with the Byzantine Empire had allowed Venice to grow incredibly rich on trade, which was exacerbated by the recent conquest of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade.

For the Paduans, the Venetians were the nouveau riche who didn’t miss a chance to flaunt their recently acquired wealth.

For the Venetians, the Paduans were the stuffy old have-been, who stuck their nose up at the Venetians, but who were clearly on the decline.

Rolandino puts the blame squarely on the Venetians, which is not very surprising as he was from Padua. The Venetian sources place the blame equally unambiguously on the Paduans.

The banner of St Mark used here was not the gold and red gonfalone with the winged lion. That flag came centuries later. Venice didn’t really have a flag in the 1200s, but the navy used a flag with St Mark standing, sometimes on a blue background.

We know this because Genoa used a similar flag with the figure of St George, which caused confusion when the navies of Venice and Genoa clashed. Their two flags were too alike to distinguish in the heat of battle.

Then, who knows, maybe bringing a flag associated with the Venetian navy, shortly after that same navy had conquered the Roman Empire, was bound to be seen as a provocation, as an act of superbia, as a statement of supremacy over the others.

But, back to the account of Rolandino da Padova:

So the Court or pastime was forthwith broken up at the bidding of the other stewards of the court and of the lord Paolo da Sermedaula, a discreet Paduan citizen of great renown who was then King of the Knights of that court, and to whom with the other stewards it had been granted, for honour’s sake, that they should have governance and judgment over ladies and knights and the whole Court.

Of this festival therefore we might say in the words of the poet, ” The sport begat wild strife and wrath ; wrath begat fierce enmities and fatal war.”

For in process of time the enmity between Paduans and Venetians waxed so sore that all commerce of trade was forbidden on either side, and the confines were guarded lest anything should be brought from one land to the other : then men practised robberies and violence, so that discord grew afresh, and wars, and deadly enmity.

So, the festival was broken up after the unauthorised skirmish between the Paduans and the Venetians, and everybody went back home with their grievances intact.

Make war, not love …

The fight in Treviso was a symptom, not the cause, and the tension, which had turned to open conflict at the Castle of Love, didn’t go away.

Venice and Padua contended some shared resources, notably the river Bacchiglione which passes through Padua and then exits a bit south of Chioggia.

The Venetians needed the river to send their goods inland, through the territory of Padua up to Vicenza.

Padua needed the river for access to the sea, but it flowed through the territory of Venice.

Like so many of the wars the Republic of Venice fought, this too was about trade and money, rather than about honour and a torn flag.

Following the “battle” at the Castle of Love, both sides blocked traffic on the river, in the hope that it would hurt the other side more.

In the autumn of 1215, Padua in alliance with Treviso sent troops down the Bacchiglione to the Torre delle Bebbe — a Venetian fortification blocking the passage towards the sea.

They attacked the tower, but were rebuffed by the garrison.

Soon after, the tide came up, much higher than normal, and flooded the area around the tower. While the garrison made a sortie, Venetian galleys came up the river with reinforcements, and the Paduans were soundly defeated.

Between three and four hundred prisoners — half of them noblemen from Padua and Treviso — were taken prisoner and brought to Venice in triumph.

Chicken peace …

No doubt, the many captured Paduan noblemen feared for their life, for having taken up arms against Venice. Woe to the vanquished, and all that.

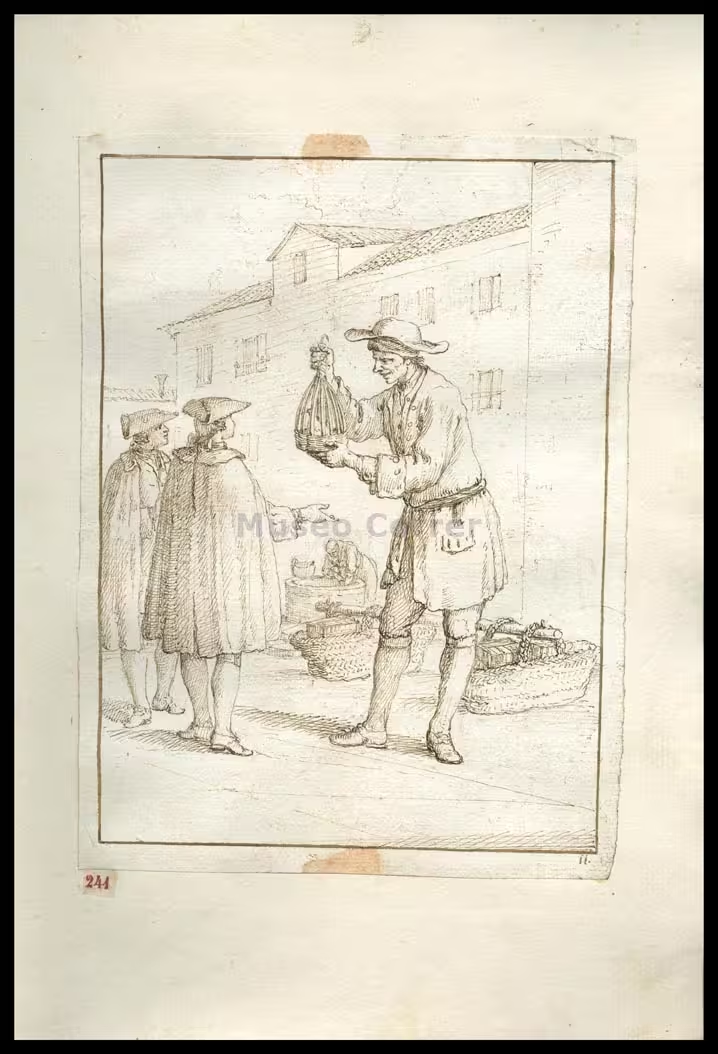

However, the doge, Pietro Ziani, decided that leniency was the better strategy, and he let all the prisoners go, on one condition: Padua would have to deliver to Venice, two white chickens for each prisoner.

So, maybe, rather than leniency, the strategy was humiliation.

One can imagine the Paduans would have preferred to pay in cash from the treasury, and then recover the money later by raising taxes and duties.

Now they had to collect 600–800 white chickens across the duchy, and transport them to Venice alive. It would be a slow, noisy and highly visible affair.

Supposedly, the Venetian crowds clamoured for the tribute to be imposed annually, but the doge said no.

In 1164, the Patriarch of Aquileia (on the mainland) had attacked the Venetian Patriarch of Grado. The Venetians had defeated and captured him, and as punishment the Patriarch of Aquileia was obliged to send twelve pigs and a bull to Venice for the carnival, each year, in perpetuity. The tribute was paid annually until 1797.

The meat of the animals was consumed during the carnival festivities, and common Venetians probably wouldn’t have said no to another annual feast with free food.

But, alas, no free food every year after the War of the Castle of Love.

Bibliography

Coulton, George Gordon. A Medieval Garner: Human Documents from the Four Centuries preceding the Reformation. London: Archibald Constable, 1910.

Muratori, Lodovico Antonio. Rerum Italicarum scriptores, 28 vols. Mediolani : ex Typographia Societatis Palatinae in Regia Curia, 1723-1751.

Leave a Reply