The casual visitor to Venice won’t see many signs of slavery, at least not at first glance.

Venetian Stories

This post is an issue of our newsletter — Venetian Stories — which goes out every few weeks, to keep in touch and share stories and titbits from and about Venice and its history.

Yet slavery was there, and it appears here and there when you look.

The painting Miracolo della Croce a Rialto by Vittorio Carpaccio from 1494 depicts a lively scene of boats on the Grand Canal and people mulling around, with the religious scene relegated to a balcony on the upper left.

In the forefront, rowing one of the many boats on the canal, is a black man.

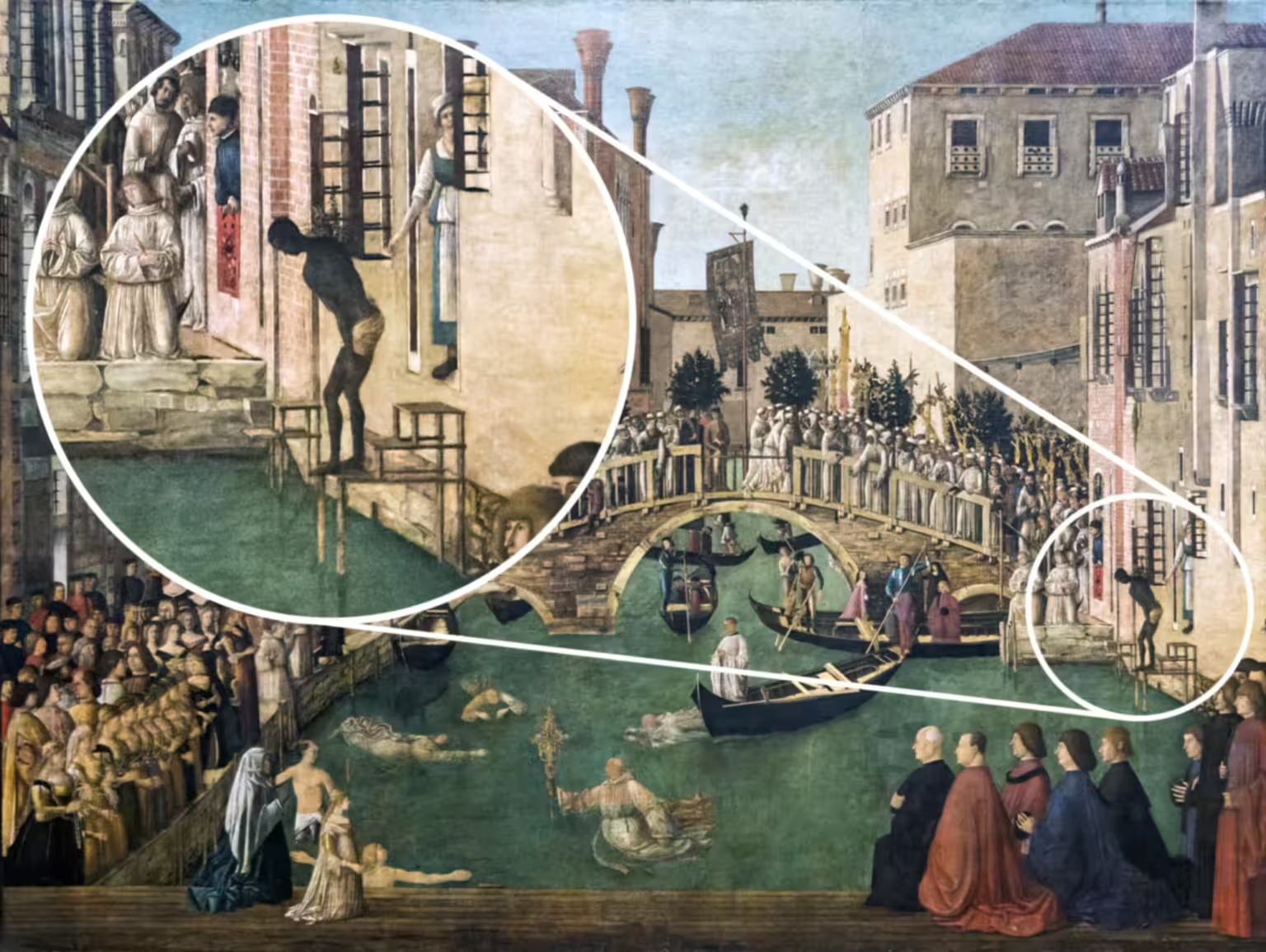

Another contemporary painting, the Miracolo della Croce caduta nel canale di San Lorenzo by Gentile Bellini (1500) also depicts a religious scene, the recovery of a relic of the Holy Cross which had fallen into the water. People are swimming in the canal, searching for the holy relic.

On the extreme right side, a black man in a loincloth is standing on some steps, either searching for the relic or preparing to dive in to recover it.

Both of these men — probably from North African — were likely slaves.

Written sources

Slaves were at the very bottom of the social hierarchy, so they rarely appear in written sources, except for the criminal records or if slaves were set free.

The merchant and explorer Marco Polo died in 1324, and his last will and testament has survived the seven centuries since. One of the provisions of his testament is:

Also, I release Peter the Tartar, my servant, from all bondage, as completely as I pray God to release my own soul from all sin and guilt.

So Marco Polo had a slave.

The name Pietro Tartaro indicates his origin somewhere in Asia, as Tartaria for the Venetians was all the land from the eastern side of the Black Sea into Mongolia.

If Marco Polo had acquired Peter during his journeys to China, Peter would have been a slave for some thirty to forty years when he was finally freed.

However, most references are from the criminal records, and generally not very nice.

In one such case from 1370, Giovanni, Pietro and Cattarina — all slaves belonging to the bishop of Eraclea — stabbed him, possibly fatally.

Giovanni was taken through the city, brutally tortured several times, and finally executed and quartered between the columns at St Mark’s. Pietro was executed and quartered after having witnessed the agony of his brother, and Cattarina was branded, had her nose cut off and was resold into slavery outside of Venice.

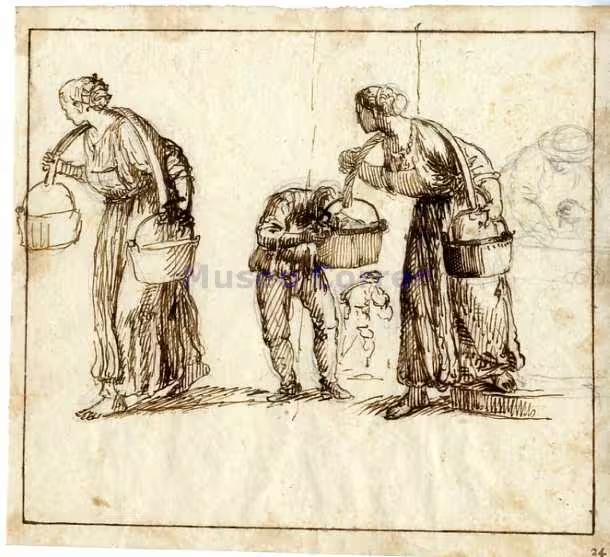

Another similar story is from 1410. Bona Tartara, a slave belonging to a Venetian aristocrat, had become pregnant with another servant from the household. Her master punished her with a severe beating with a yoke used for carrying water from the wells. The documents don’t say, but one can imagine she lost the baby. In any case, she went to a pharmacy, bought arsenic and laced her master’s soup with it. He died in agony several days later.

She was taken by boat down the Grand Canal, while a herald cried out her crime, and then dragged after a horse back to St Mark’s where she was burned.

Not all criminal cases saw the slave as the offender.

In one case, a female slave servant in a monastery was freed after she testified against her mistress in a case of sexual encounters in a nunnery.

Even nuns could keep enslaved servants.

Names and origins

All the enslaved persons mentioned above had good Venetian names.

While formally, it wasn’t legal to keep other Christians as slaves, in practice all slaves brought to Venice were baptised and given Venetian names.

If such enslaved persons had surnames, they were simply geographical references to where more or less they came from. Hence, the surname Tartaro or Tartara for those coming from the Tartaria.

Slavery is rarely limited to just taking people’s freedom and labour from them. They are often also deprived of their identity and beliefs.

Many slaves came from the northern and eastern parts of the Black Sea, where many people hadn’t yet converted to Christianity in the Middle Ages. Being neither Christians nor Muslims made the people there easier to sell on a wide range of slave markets around the Black Sea and the Mediterranean.

The word ‘slave’ is derived from the word ‘Slav’, and is connected to the Venetian greeting ciao as well.

Laws and the State

Even though the Pope tried to ban the slave trade, the Venetians continued anyway. The business was simply too lucrative.

Like with any other goods, the Venetian trade often served markets elsewhere. Not all the slaves traded were brought to Venice.

The Venetian state had no issues with slavery or the trade in slaves.

During the War of Chioggia (1379–1381) a tax was levied on owners of slaves to finance the war.

Ships bringing slaves to Venice had to declare their goods on arrival, including the number of ‘souls’ and their origin, and pay an import duty for each slave.

A law from 1459 explicit decried the scarcity of slaves male and female to serve the nobility and citizens of Venice. Such penuria of slaves led to taxes on the exportation of slaves from Venice.

The Venetian navy — especially on the rowed galleys — used slaves and forced labour in large numbers. Rowers were chained to the benched as the war galleys entered battle.

In some cases, Venetian slave owners placed their slaves as ‘volunteers’ in the galleys, to cash in the wages they were paid by the navy.

The Venetian noblemen Domenico Pizzamano served as a commander of a war galley in the late 1700s. On his return to Venice after a five-year term, he was praised for only having lost thirty percent of the rowers on his galley. Clearly, the expectation was that more than a third of the rowers on a galley would perish over a five-year period, with the associated costs for the state.

The end of slavery

The Republic of Venice never abolished slavery.

Rather, the republic itself was abolished in 1797, and with that, all the laws of the republic went out of force.

The abolishment of slavery in Venice would befall one of the successor states to the Republic of Venice.

Leave a Reply