In late January 1751, all the talk in Venice was about Clara.

Venetian Stories

This post is an issue of our newsletter — Venetian Stories — which goes out every few weeks, to keep in touch and share stories and titbits from and about Venice and its history.

She had come to Venice for the Carnival, and everybody wanted to go and see her.

Clara was the stuff of legends.

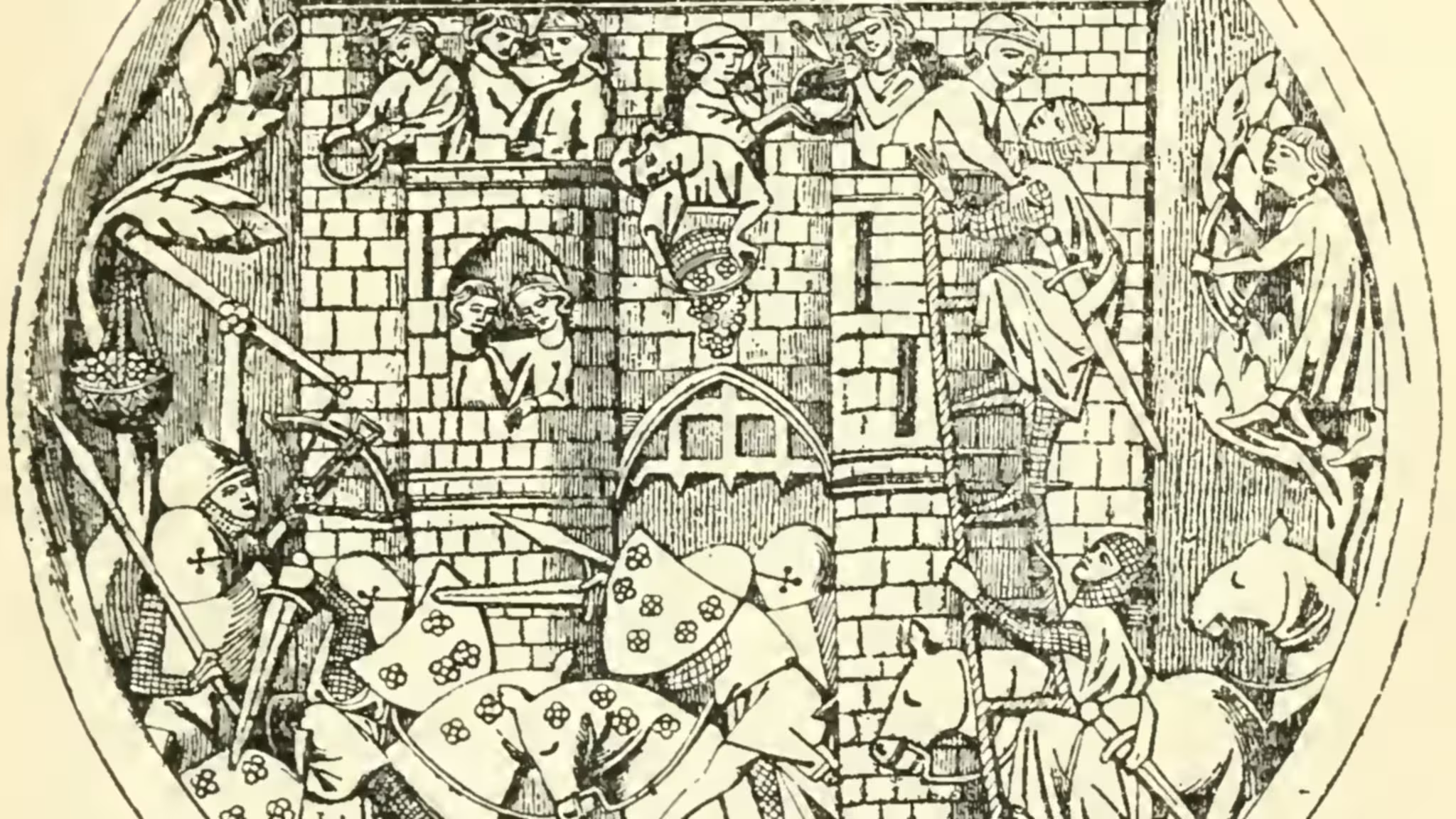

In fact, an ancient tale said that there had been somebody like Clara in Venice in the mid-1300s, during the reign of doge Andrea Dandolo. The proof was a small mosaic in a chapel in St Mark’s Basilica, built at that time.

What was certain, however, was that nobody like Clara had set hoof in Venice for centuries.

Clara was a rhinoceros

In 1738, in Bengal (modern-day Bangladesh) hunters killed Clara’s mother, and the rhinoceros cub was taken in by a director of the VOC — the Dutch East India Company.

Two years later, he later sold or gave the young rhino to a Dutch captain, Douwe Mout van der Meer, who took her to the Netherlands.

For the next seventeen years, Clara and Mout van der Meer toured much of Europe, where the latter made quite a bit of money out of putting the former on display.

According to the contemporary artist Grevembroch, the rhinoceros was

captured in the States of the Great Mogul. Captain Davide Moutuander-Meer also transported it here for Carnival of the year 1750 in 22 January, on a covered wagon, pulled by many horses.

Clara was transported around Europe in a specially made closed carriage, drawn by eight horses.

Apparently, the horn fell off in Rome at some earlier time, which is why Clara is often depicted without a horn, and Mout van der Meer with it in his hand.

Rhinoceroses were considered almost magical beings. John Evelyn, in his diary, tells of a well inside the Venetian arsenal, which supposedly contained two rhino horns, and therefore always provided good water which couldn’t be poisoned.

The Venetian Carnival

The Carnival in Venice was a raucous affair, which attracted people from all over Europe, and it was an obligatory stop for anybody doing the Grand Tour in Italy.

For an entrepreneurial spirit like Mout van der Meer, it was the perfect place and time to make some money.

The area of St Mark’s was full of temporary buildings and stages, where all sorts of curiosities were on display, be it astrologers, magicians, snake-oil salesmen, vagrant theatres, or exotic animals.

This was just the right place to be for the owner of a famous travelling rhinoceros.

Grevembroch wrote:

This great Beast ate twenty pounds of bread, sixty of hay, and drank fourteen buckets of water, or even beer. It weighed about five thousand pounds of 18 ounces, and through universal curiosity, the Master profited here, about four thousand ducats, most of which he left on the Tables of the Ridotto

It is difficult to put an order of magnitude on such a sum, but it was a substantial amount of money that Mout van der Meer earned and lost.

The Ridotto in the Palazzo Dandolo at San Moisè was the official casino in Venice, and a central part of Carnival entertainment for the wealthy.

The lasting legacy of Clara

Clara’s stay in Venice resulted in at least four works of art: two paintings by Pietro Longhi; an etching by his son Alessandro Longhi; and a watercolour by Giovanni Grevembroch.

They’re all from the time just around the time Clara and Mout van der Meer were in Venice.

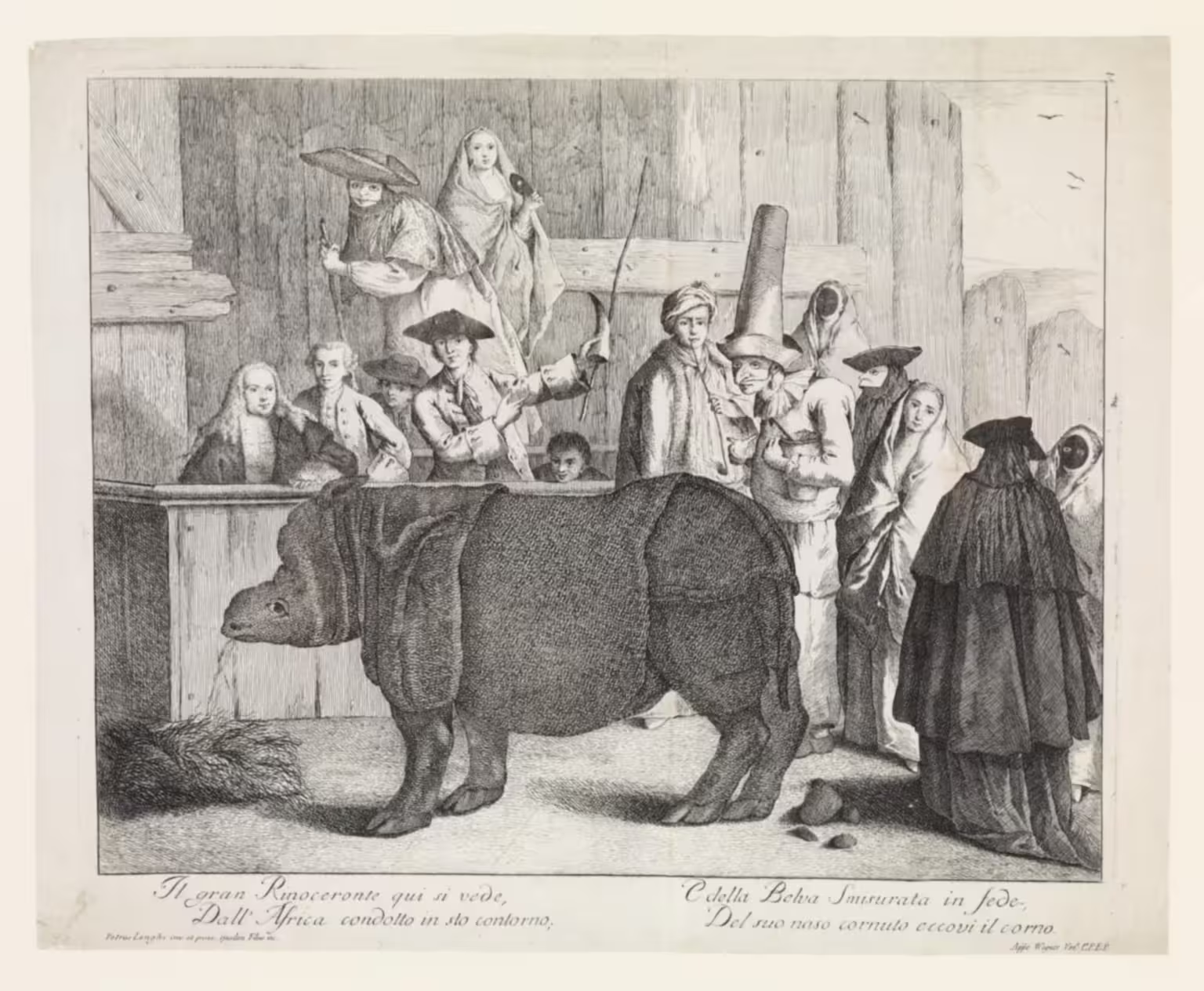

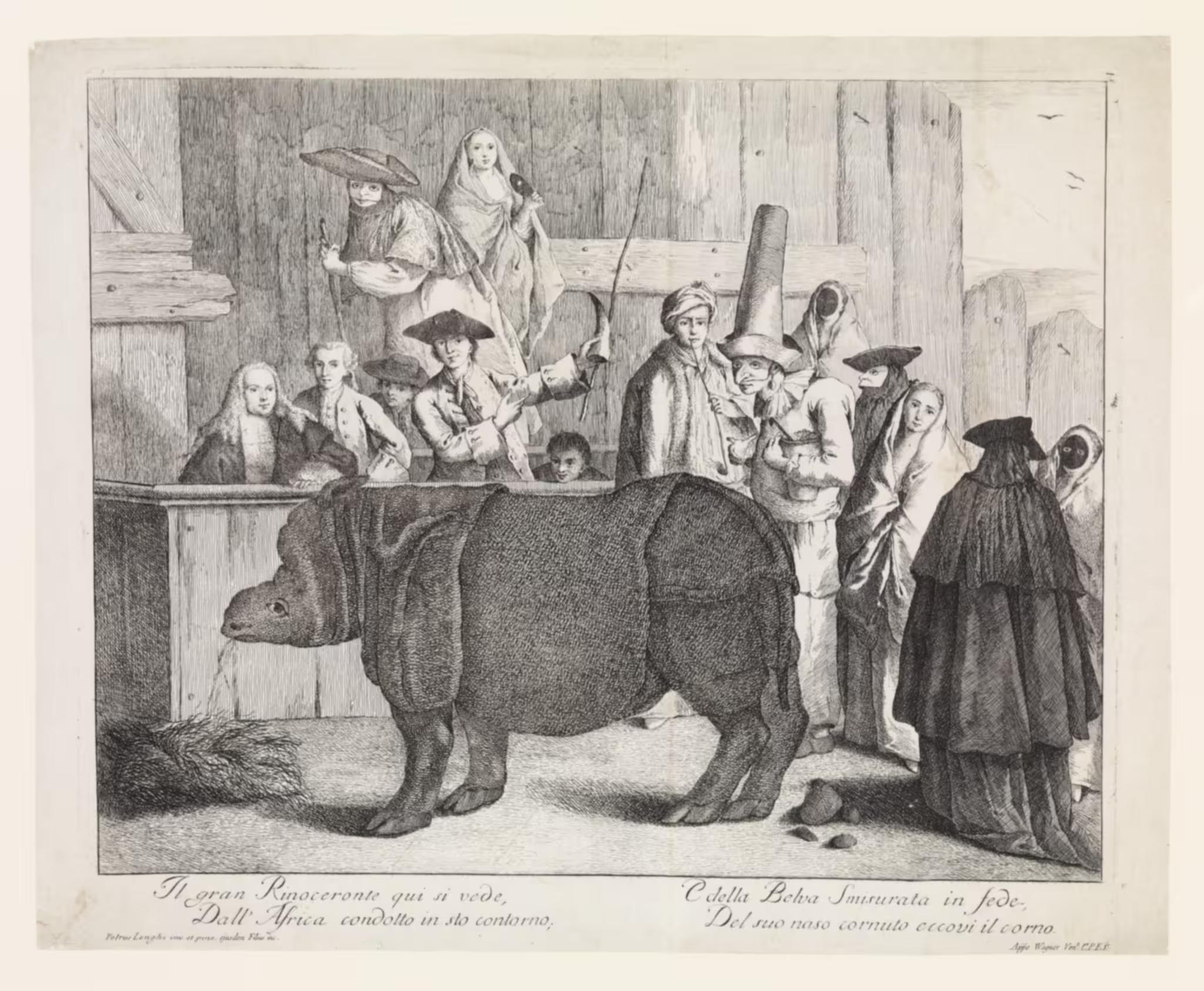

Pietro Longhi — Il rinoceronte

The two paintings by Pietro Longhi (1701–1785) are very similar, but not identical.

One was commissioned by the Venetian nobleman Giovanni Grimani, as it evident from what is written on a note nailed to the wall on the right side of the painting.

Vero Ritratto Di un Rinocerotto condotto in Venetia L’anno 1751 fatto per mano di Pietro Longhi per Commissione del N.O. Giovanni Grimani dei Servi Patrisio Veneto.

Which translates as: “Real portrait of a rhinoceros taken to Venice in the year 1751 made by the hand of Pietro Longhi by commission of the nobleman Giovanni Grimani of the Servites Venetian Patrician.”

Giovanni Grimani had a menagerie of exotic animals in his villa on the Venetian mainland, which explains his particular interest in Clara.

He was 23 years old at the time, and just married to Catarina Contarini, who died shortly after, having given birth to their only child. They are supposedly represented in the painting.

The man, who is holding the whip and the horn, is probably Douwe Mout van der Meer.

This painting is on display in the Ca’ Rezzonico museum in Venice.

The second painting by Pietro Longhi, most likely made a bit later, is very similar, but the written notice on the wall is missing, and the two unmasked men in the first painting are now masked.

A recent reframing of the painting revealed a dedication on the back of the canvas: “per commissione del Nobile Uomo Sier Girolamo Mocenigo Patrizio Veneto” — “by commission of the nobleman sir Girolamo Mocenigo Venetian Patrician.”

This painting is now in the National Gallery in London, UK.

Alessandro Longhi

Alessandro Longhi, the son of Pietro, later made an acqueforte (an engraving using acid) with a similar motif, but with a lot more common people present.

This was probably an attempt at making a more commercial offering, producing an image with a wider appeal, in greater numbers.

The short poem under the image reads:

Il gran rinoceronte qui si vede

Dall’Africa condotto in sto contorno

E della belva smisurata in fede

Del suo naso cornuto eccovi il corno

Which in my translation is:

The great rhinoceros you here see

Taken from Africa to this place

And of the outsized beast, honestly,

From his horned nose, here is the horn

The line at the bottom reads: “Pietro Longhi created and painted it; his son etched it,” and “Published by Wagner, C.P.E.S.”, which refers to the printer Joseph Wagner (1706–1780). The abbreviation stands for “Cum Privilegio Excellentissimi Senatus” — with licence of the Most Excellent Senate.

No painting by Pietro Longhi matching this engraving has survived.

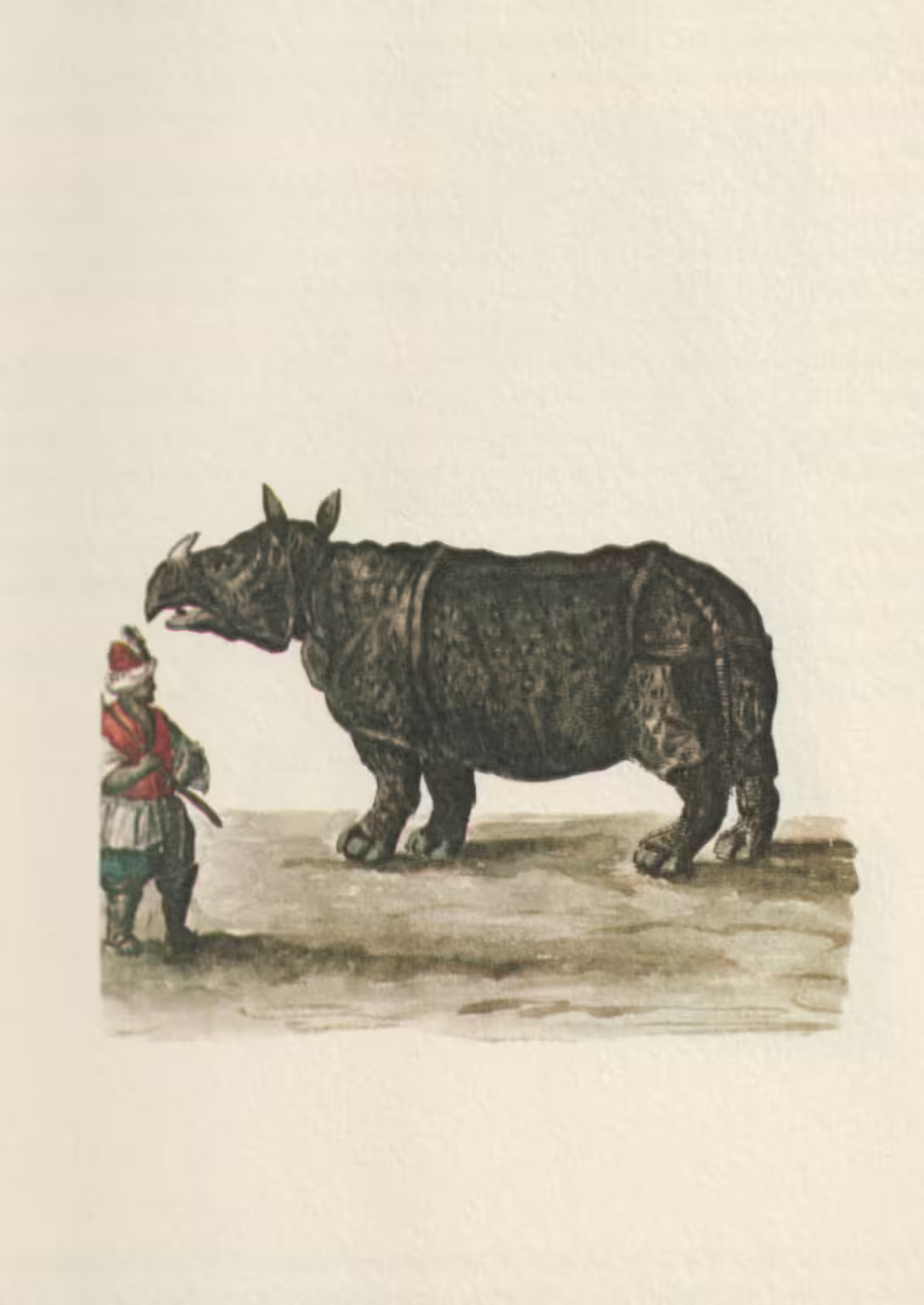

Giovanni Grevembroch

The last work hasn’t received as much attention as the others. Giovanni Grevembroch was a kind of house artist for the Venetian nobleman Pietro Gradenigo for several decades in the mid-1700s.

Most of the commissions he got were for documenting various aspects of Venetian life and culture.

The image of Clara the rhinoceros was clearly added as a curiosity at the end of what should have been the last volume of a work with six hundred watercolours on how the Venetians dressed.

The original is in the archive of the Museo Correr in Venice. Much of Grevembroch’s work is in such a pitiful state of conservation that it cannot be consulted, but the four volumes on how the Venetians dressed were re-published in the 1980s.

The end of Clara

Douwe Mout van der Meer continued travelling Europe with Clara for seventeen years. She died in England in 1758, at an age of around twenty years. Rhinos have a natural lifespan of 40–45 years.

Related articles

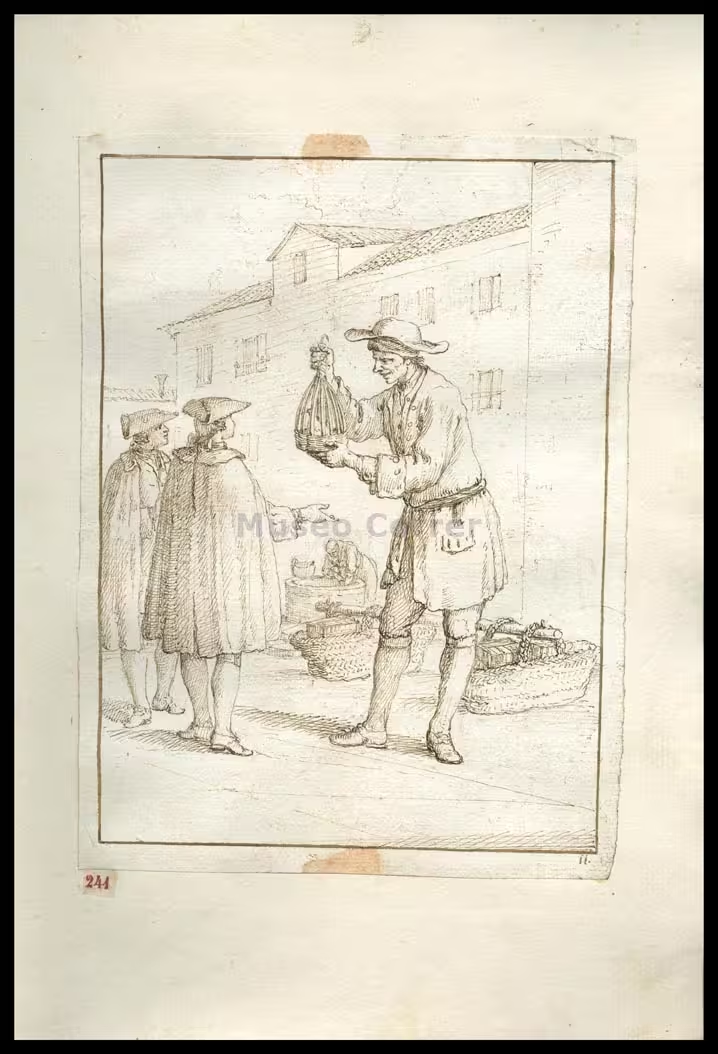

- Marmotina — street entertainer with a trained marmot

- Fa ballar i Cani — street entertainer with dancing dogs

- Gli abiti de veneziani — by Giovanni Grevembroch

- An Englishman in Venice — the diary of John Evelyn — 1645

Leave a Reply