We don’t know exactly when Marco Polo died, but the date of his last will and testament is January 9th, 1323 M.V., i.e., in the year 1324, seven centuries ago today.

He most likely died within a short time of this date, as his stated purpose of calling the priest and notary was that he felt the end was near.

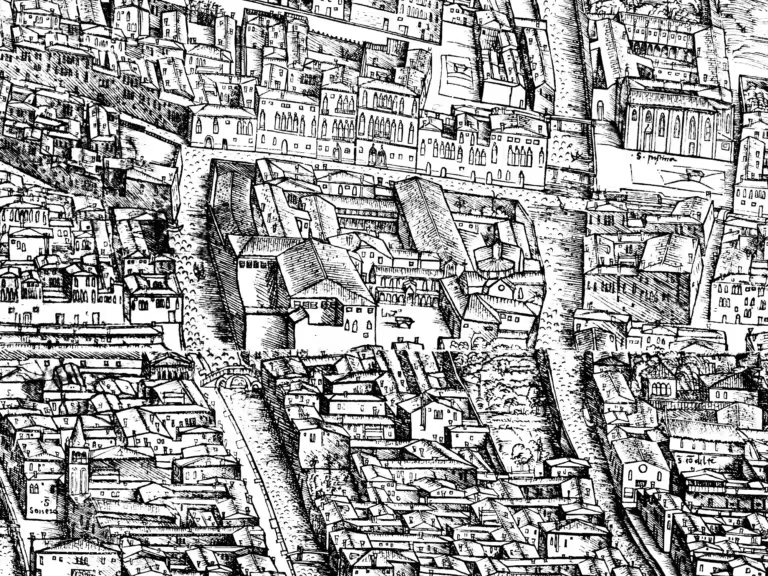

The house of Marco Polo

The house where Marco Polo and his family lived was in the area of the Corte Seconda del Milion in Cannaregio. In the early 1300s, stone houses were rare and expensive. The Polo family, however, was not poor, so their house might have been in stone, even if most of the houses in Venice were still wooden structures.

According to Tassini, in his Curiosità Veneziane, the house burned in 1597, when it appeared in a legal document as an “ancient house destroyed to the foundations.” In the late 1600s, the Teatro di San Giovanni Gristostomo was built on the site, since replaced by the building of the modern Teatro Malibran.

Interestingly, there are many pieces of medieval Byzantine artwork, such as paterae, reliefs and crosses, from the time of Marco Polo, on other buildings in the Corte Seconda del Milion. If the house of the Polo family was in stone, it would probably have looked like some of the surviving buildings in the area.

Marco Polo requested to be buried in the monastery of San Lorenzo, rather than in the local parish church of San Giovanni Grisostomo. Most likely this was where his father laid, so there was some kind of connection.

There are no surviving remains of the burials of the Polo family at San Lorenzo. The church was completely rebuilt in the late 1500s, and the medieval monastery is also gone. Everything from the time of Marco Polo has disappeared.

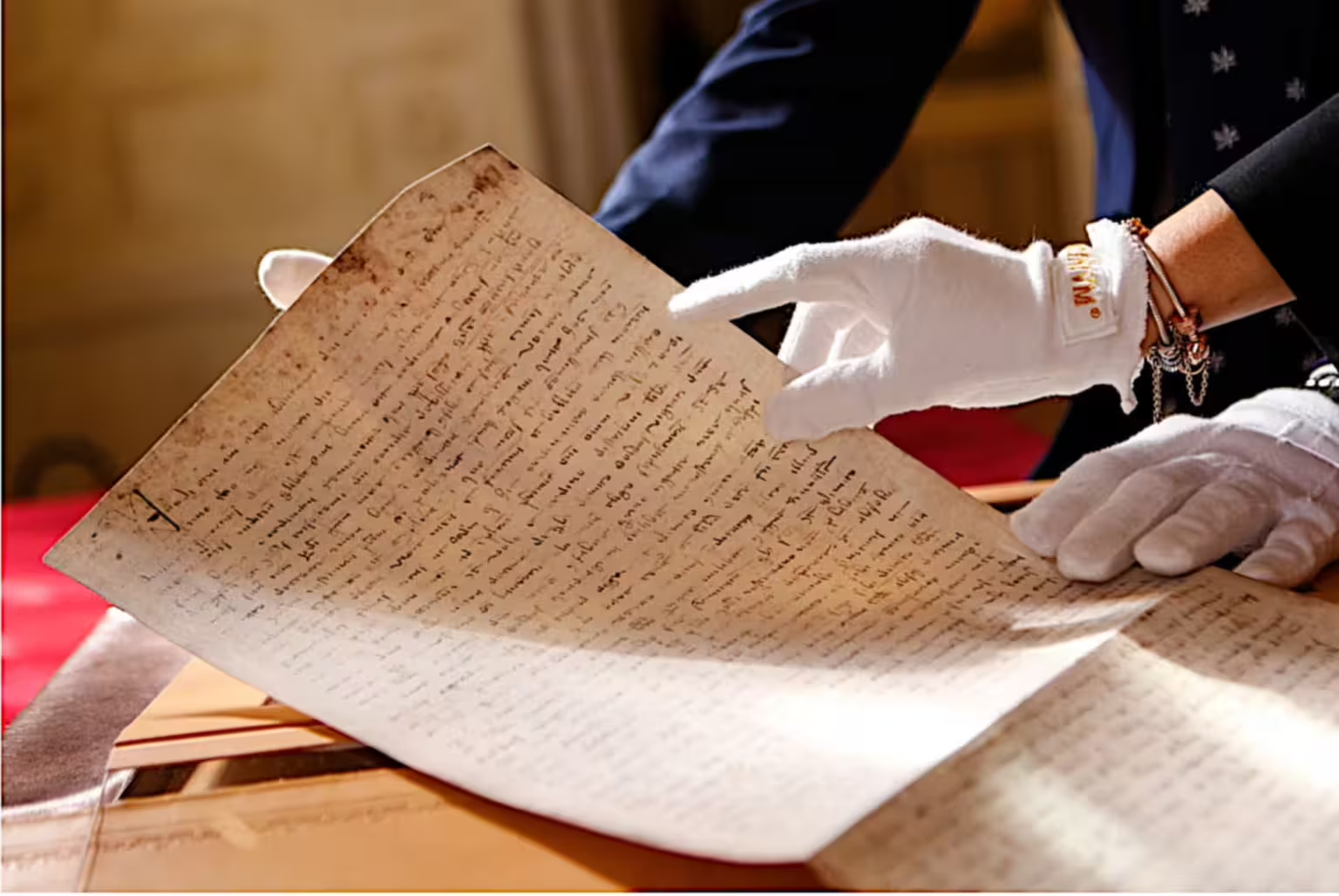

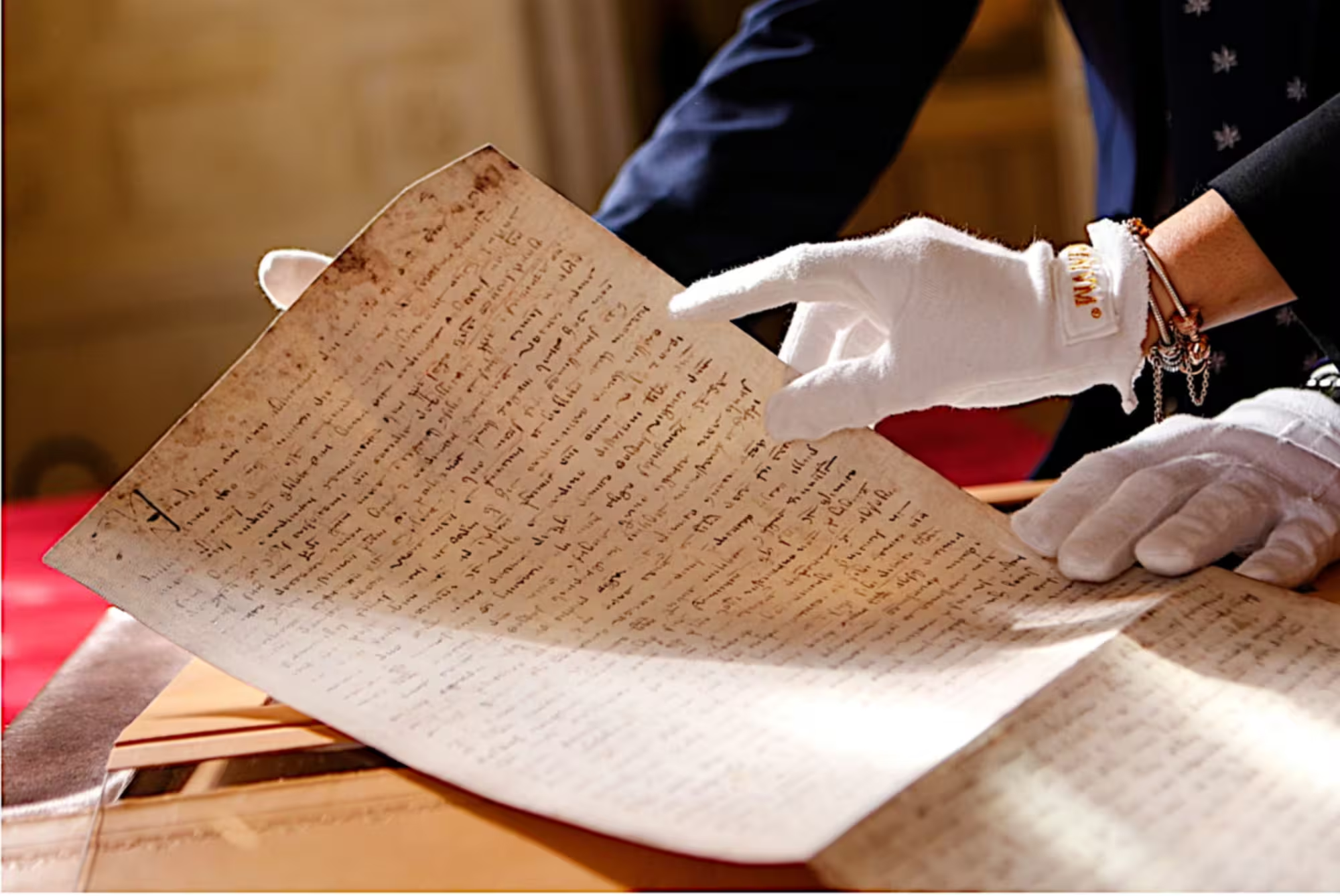

The document

The testament of Marco Polo is in the Marciana Library in Venice.

It is a large piece of vellum, high-quality parchment made of calf-skin, over 60cm long, (badly) written in a Carolingian miniscule hand.

The priest and notary Giovanni Giustiniani wrote the document, in the presence of Marco Polo, who dictated his last will on his deathbed.

Marco Polo didn’t sign the testament himself. He probably signed it symbolically by the signum manus, by simply touching the parchment in the presence of witnesses. The signatures on the document are by the notary Giustiniani and two other witnesses.

A translation

In the Name of the Eternal God, Amen!

In the year from the Incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ 1323, on the 9th day of the month of January, in the first half of the 7th Indiction, at Rialto.

It is the counsel of Divine Inspiration as well as the judgment of a provident mind that every man should take thought to make a disposition of his property before death become imminent, lest in the end it should remain without any disposition.

Wherefore I Marcus Paulo of the parish of St. John Chrysostom, finding myself to grow daily feebler through bodily ailment, but being by the grace of God of a sound mind, and of senses and judgment unimpaired, have sent for John Giustiniani, Priest of S. Proculo and Notary, and have instructed him to draw out in complete form this my Testament.

Whereby I constitute as my Trustees Donata my beloved wife, and my dear daughters Fantina, Bellela, and Moreta, in order that after my decease they may execute the dispositions and bequests which I am about to make herein.

First of all: I will and direct that the proper Tithe be paid. And over and above the said tithe I direct that 2000 lire of Venice denari be distributed as follows:

20 soldi of Venice grossi to the Monastery of St. Lawrence where I desire to be buried.

Also 300 lire of Venice denari to my sister-in-law Ysabeta Quirino, that she owes me.

Also 40 soldi to each of the Monasteries and Hospitals all the way from Grado to Capo d’Argine.

Also I bequeath to the Convent of SS. Giovanni and Paolo, of the Order of Preachers, that which it owes me, and also 10 lire to Friar Renier, and 5 lire to Friar Benvenuto the Venetian, of the Order of Preachers, in addition to the amount of his debt to me.

I also bequeath 5 lire to every Congregation in Rialto, and 4 lire to every Guild or Fraternity of which I am a member.

Also I bequeath 20 soldi of Venetian grossi to the Priest Giovanni Giustiniani the Notary, for his trouble about this my Will, and in order that he may pray the Lord in my behalf.

Also I release Peter the Tartar, my servant, from all bondage, as completely as I pray God to release mine own soul from all sin and guilt. And I also remit him whatever he may have gained by work at his own house; and over and above I bequeath him 100 lire of Venice denari.

And the residue of the said 2000 lire free of tithe, I direct to be distributed for the good of my soul, according to the discretion of my trustees.

Out of my remaining property I bequeath to the aforesaid Donata, my Wife and Trustee, 8 lire of Venetian grossi annually during her life, for her own use, over and above her settlement, and the linen and all the household utensils, with 3 beds garnished.

And all my other property movable and immovable that has not been disposed of [here follow some lines of mere technicality] I specially and expressly bequeath to my aforesaid Daughters Fantina, Bellela, and Moreta, freely and absolutely, to be divided equally among them. And I constitute them my heirs as regards all and sundry my property movable and immovable, and as regards all rights and contingencies tacit and expressed, of whatsoever kind as hereinbefore detailed, that belong to me or may fall to me. Save and except that before division my said daughter Moreta shall receive the same as each of my other daughters hath received for dowry and outfit [here follow many lines of technicalities, ending]

And if any one shall presume to infringe or violate this Will, may he incur the malediction of God Almighty, and abide bound under the anathema of the 318 Fathers; and farthermore he shall forfeit to my Trustees aforesaid five pounds of gold; and so let this my Testament abide in force. The signature of the above named Messer Marco Paulo who gave instructions for this deed.

I Peter Grifon, Priest, Witness.

I Humfrey Barberi, Witness.

I John Giustiniani, Priest of S. Proculo, and Notary, have completed and authenticated

Translation by Henry Yule, from Polo, Marco. The travels of Marco Polo : the complete Yule-Cordier edition, 2 vols. New York Dover, 1993, vol. 1.

Some comments

The date of the testament is January 1323. However, in the Venetian calendar the year started in March, so January 1323, more veneto, is in 1324 for us.

The words “the seventh indiction” refers to an ancient Roman period of reassessment of taxation, which was still in use for formal dates in the Middle Ages.

The place is given as Rialto. The house of Marco Polo at San Giovanni Grisostomo is near the Rialto area, but in the Middle Ages Venice was the state, while the city was Rialto.

Donations

The tithe (decima) was a ten percent tax to the church, in this case to the Bishop of Olivolo.

A lira (from Latin libra, a pound) was 20 soldi. One soldo was 12 denari. The denari were the only denomination of real coins at the time of Marco Polo. Due to inflation of the silver contents of the coins, many other denominations appeared, such as lira di grossi. A lira and a lira di grossi are not the same.

“All the way from Grado to Capo d’Argine” meant the entire ancient dogado, the lagoon settlements which constituted the original Venetian state. Grado is in a now separate lagoon to the north, while Cavarzere is south of the current lagoon.

Charity, often in the form of donations to churches or monasteries, were a religious obligation for the wealthy. It is quite explicit in the Bible, for example with the camel and the eye of a needle.

Marco Polo, being a wealthy man, needed to fulfil his Christian obligations for the salvation of his soul.

Likewise with the forgiveness of debts.

Slavery

A last act of charity was the release of his servant Peter the Tartar “from all bondage.”

What kind of servant is in a state of “bondage”?

Marco Polo owned a slave.

If Peter the Tartar was as he was called, he must have arrived in Venice with Marco Polo on his return from Central Asia in 1295. In that case, Peter had lived in Venice for almost thirty years as an indentured servant to Marco Polo. The journeys of Marco Polo lasted almost two decades, so the servitude of Peter might have been much longer.

It is clear that Peter lived in a separate household. However, Marco Polo probably owned the house Peter lived in, as he explicitly ceded the value of all the improvements made to it by Peter.

This was not chattel slavery, but a kind of household slavery which was very common in Medieval Europe. On a curious aside, the Venetian word ciao is most likely related to the Venetian slave trade.

Peter was most likely an exotic status symbol for Marco Polo, besides a faithful servant. Owning a slave servant of distant origin was a status symbol, as such persons were rare and expensive.

Such slaves even appear in later works of art. A painting by Vittorio Carpaccio, called The Miracle of the Holy Cross at Rialto, shows such a slave rowing a boat (a precursor of the gondolas) on the Grand Canal. He is dressed in fine and expensive clothes, exactly because it is a status symbol.

Wife and daughters

The importance of charity towards the church is evident in the order of the dispositions. He specified all the debts rescinded, donations destined for the church and the freeing of his slave servant before he took care of his wife and daughters.

His wife Donata Badoer received an annuity “over and above her settlement.” That was her dowry, i.e., her paternal inheritance, returning into her possession and control.

She also received “the linen and all the household utensils, with 3 beds garnished.”

That might not sound like a lot to modern ears, but before the industrial revolution, fabric and clothes were all hand-made, from the cleaning, carding and threading of the fibres, to weaving and sewing the clothes. This was all very labour-intensive.

A fine lady’s dress might have taken years of work, so the value of the dress would need to account for that time as well as the material used. Linen and clothes could therefore represent a substantial value.

With the industrial revolution, some of the very first mechanic production processes were exactly threading and weaving. That was no accident.

Apparently, his two oldest daughters, Fantina and Bellela had already married. Marco Polo explicitly stipulated that Moreta should receive her dowry and expenses for the wedding, to an equal amount as the others.

The “the 318 Fathers” is a reference to the participants of the Council of Nicea in 325.

Links and references

- Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana – Venezia — Il Testamento di Marco Polo (since deleted);

- Teaching Medieval Slavery and Captivity – Source: Marco Polo’s Will;

- A luxury facsimile of the testament – Ego Marcus Paulo volo et ordino.

Bibliography

- Polo, Marco. The travels of Marco Polo : the complete Yule-Cordier edition, 2 vols. New York Dover, 1993. 🔗

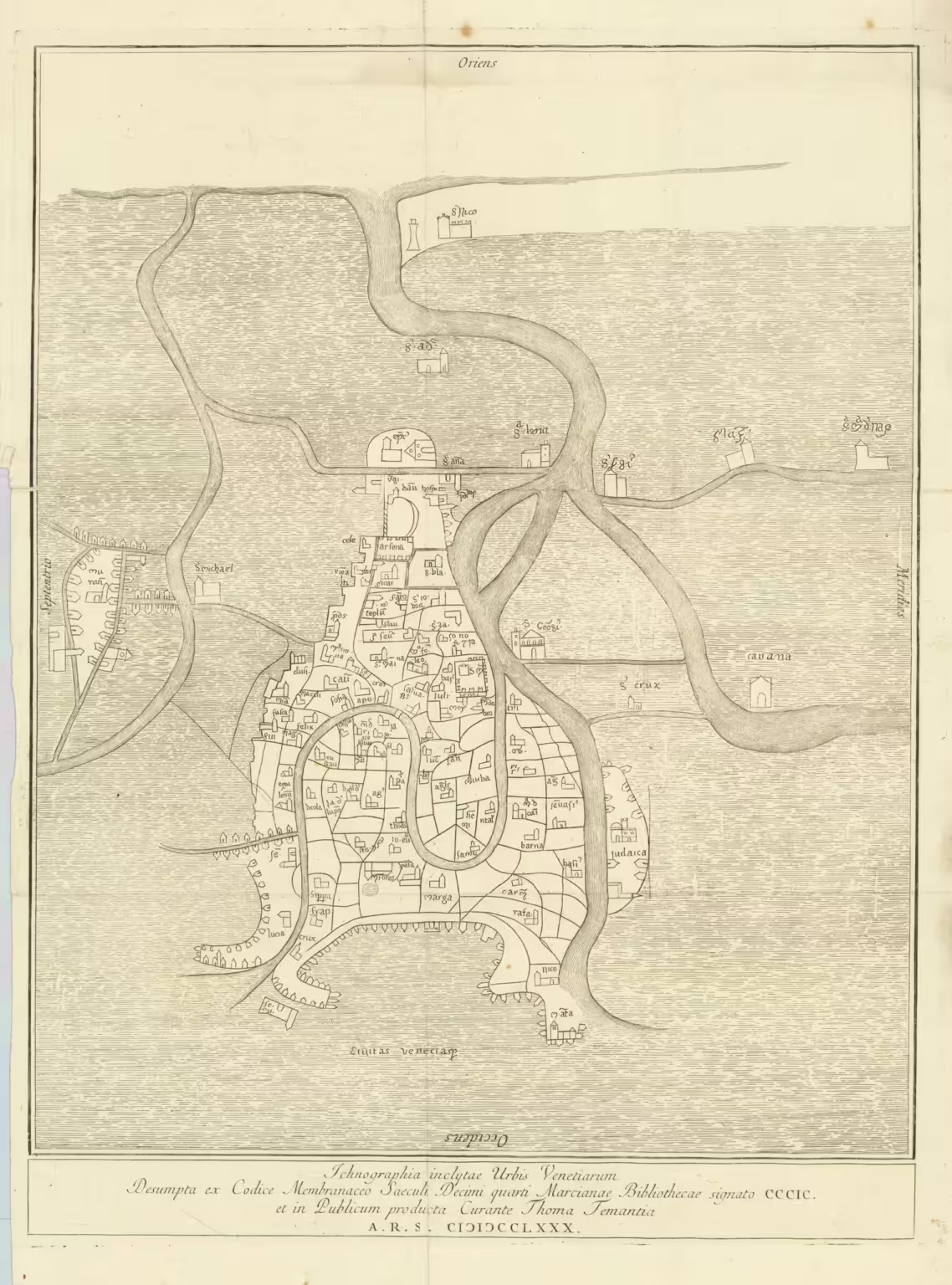

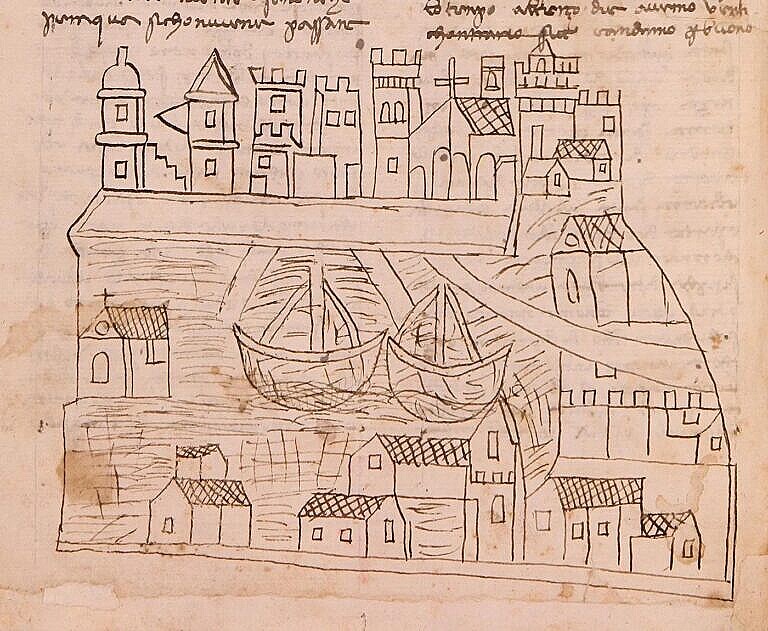

A note on maps and artworks

The view of Venice by Jacopo de’ Barbari used above is from 1500. The painting by Carpaccio is from around 1496.

Neither are contemporary with Marco Polo — they’re almost two centuries later.

The problem is that we don’t have that kind of material from the early 1300s. Or rather, we have some, but it is very different from what we would consider useful.

Here’s a map and a drawing of Venice from shortly after the death of Marco Polo.

Leave a Reply