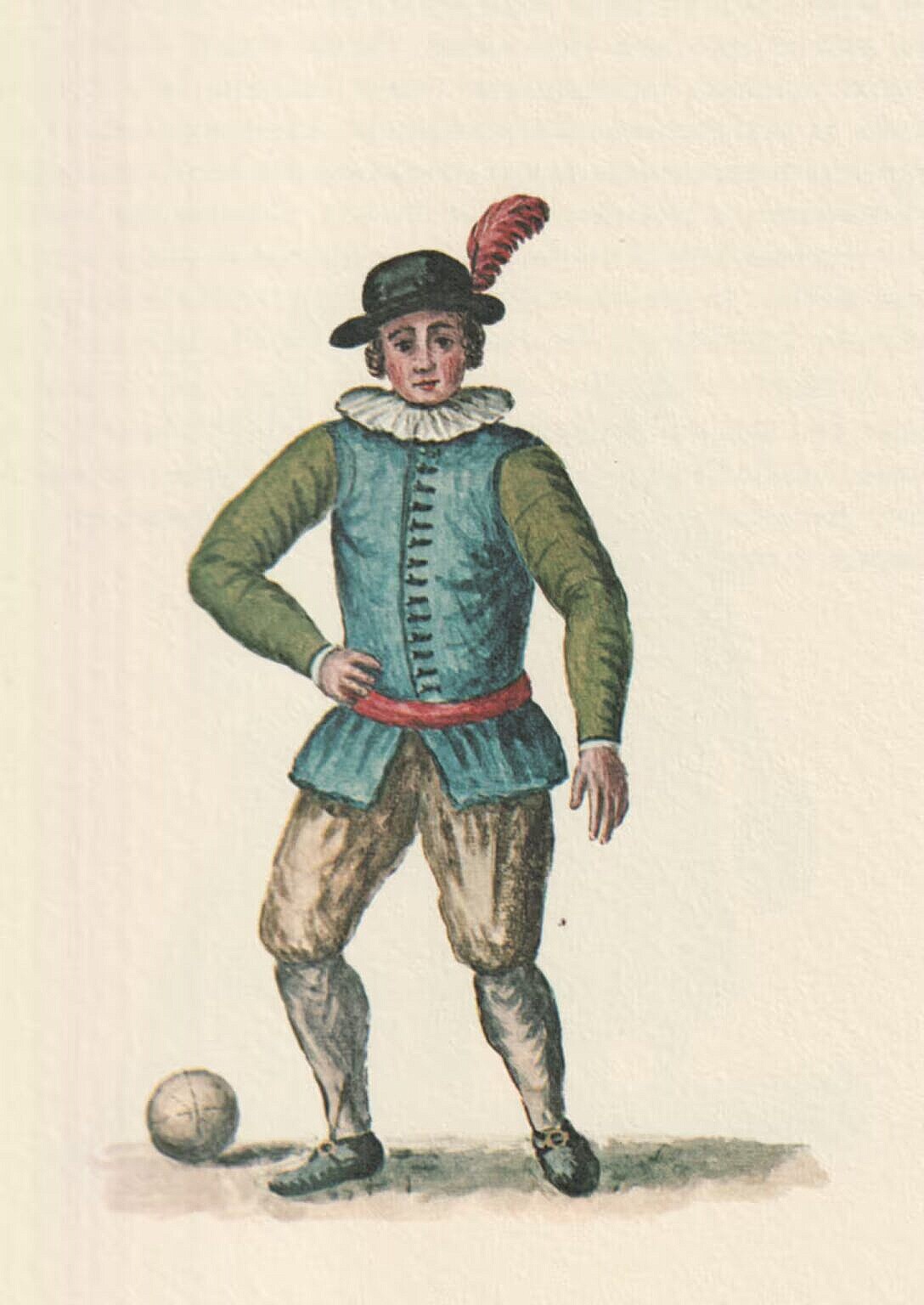

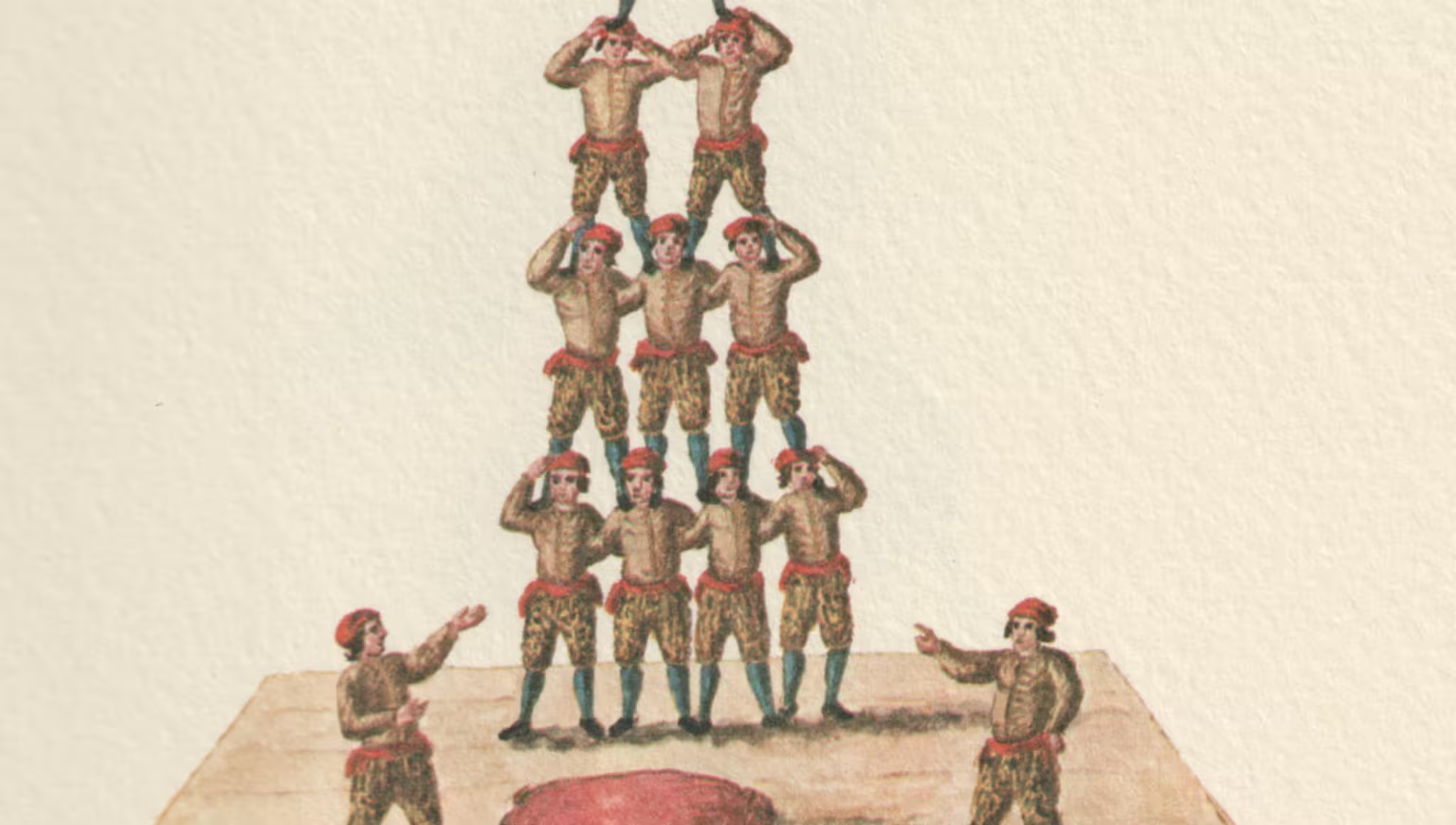

This painting depicts a nobleman dressed for a game of calcio, a rugby like game which was popular during Lent.

A treatise on ball games, published in 1555, refers to the game of calcio not as matches, but as battles.

Source: Gli abiti de veneziani di quasi ogni età con diligenza raccolti e dipinti nel secolo XVIII, by Giovanni Grevembroch (1731–1807), which in four volumes contains over six hundred watercolours of how Venetians dressed in the 1700s.

Nobleman at the game of Calcio

In times past, Youth practiced crossbow shooting because it was mandated by law that even the nobility should go to the Lido on holidays, so that through this means they could become robust and capable of the necessities of war. The same activity was carried out for the city districts, and for this purpose, in the 14th century, boat races were also invented, teaching men to row well at the same time.

After the use of Artillery was discovered, the Bow was set aside; but the Patricians introduced during the Summer, to keep themselves agile and capable of hard work, a Game that they called Calcio.1 They divided themselves into two numerous factions on the shooting grounds, one called that of the Mountain and the other from the Plain; and they separated the Field with one or two large Portals of Stucco or wood. The Game began from one of the sides alternately on the given signal, to pass the same Portal, in order to recover a Ball thrown from there. The Opponents skilfully opposed them, while keeping their Arms tightly joined to their Sides (as it was forbidden to use their Hands) so that with the sole strength of their Shoulders, they made a vigorous defence and the Victory, acquired in the presence of countless Spectators surrounding the Fence, was highly valued. They were dressed in undergarments with Sleeveless vests, with Caps or Hats with a red or black Feather, each according to the Uniform of their own Company.

In the centuries long past

when Venice made the water and the land tremble,

to give perpetual banishment from the City

to idleness, which buries human glory,

The Politicians went inventing

a game, which had the form of war,

in which often using their chests,

they filled the Young Men with courage.

To the heroic prerogatives lauded everywhere of His Excellency Lord Count Giovanni Battista Fioravanti of Salò, we take the opportunity to present a respectful offering of our love, as he will know that in 1692 here Gio. Cagnolini printed a beautiful discourse on the origin and rules of this game.2

Translator’s notes

- The word calcio means to kick, and it is the same word used today for modern football (soccer). The actual game played would have been different, and maybe more like Tuscan ‘historic’ football. ↩︎

- I haven’t been able to locate this text, but it probably existed in Pietro Gradenico’s vast library. ↩︎

Original text

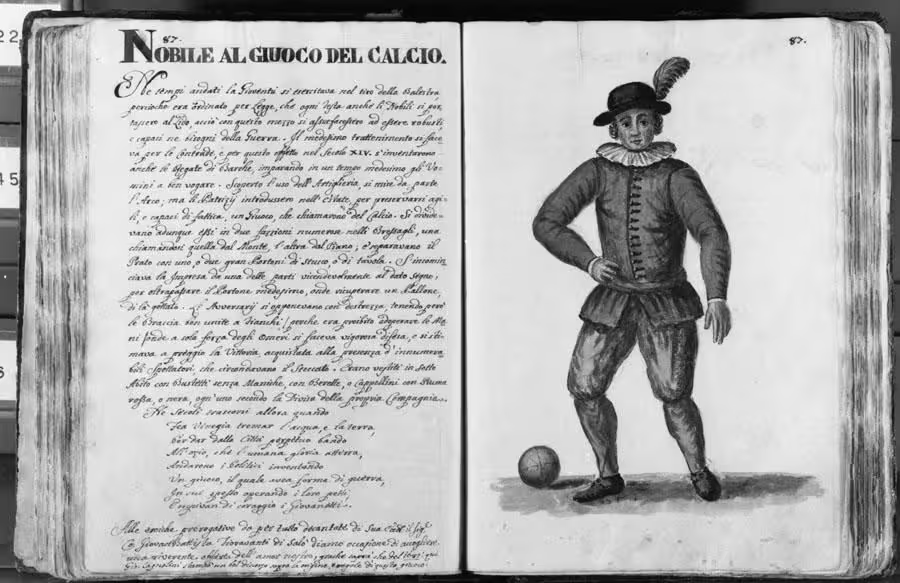

Nobile al Giuoco del Calcio

Ne tempi andati la Gioventù si esercitava nel tiro della Balestra, percioche era ordinato per Legge, che ogni festa anche li Nobili si portassero al Lido, acciò con questo mezzo si assuefacessero ad essere robusti, e capaci ne bisogni della Guerra. Il medesimo trattenimento si faceva per le Contrade, e per questo effetto nel Secolo XIV s’inventarono anche le Regate di Barche, imparando in un tempo medesimo gli Uomini a ben vogare.

Scoperto l’uso dell’Artiglieria, si mise da parte l’Arco; ma li Patrizij; introdussero nell’Estate, per preservarsi agili, e capaci di fattica, un Giuoco, che chiamarono del Calcio. Si dividevano adunque essi in due fazzioni numerose nelli Bressagli, una chiamavasi quella del Monte l’altra dal Piano; e separavano il Prato con uno, o due gran Portoni di Stucco, o di tavola. S’incominciava la Impresa da una delle parti vicendevolmente al dato segno, per oltrapassare il Portone medesimo, onde ricuperare un Pallone, di là gettato. Li Avversarij si opponevano con destrezza, tenendo però le Braccia ben unite a Fianchi (perche era proibito adoperare le Mani) onde a sola forza degli Omeri si faceva vigorosa difesa, e si stimava a preggio la Vittoria, acquistata alla presenza d’innumerabili Spettatori, che circondavano il Steccato. Erano vestiti in sotto Abito con Bustetti senza Maniche, con Berette, o Cappellini con Piuma rossa, o nera, ogn’uno secondo la Divisa della propria Compagnia.

Ne Secoli trascorsi allora quando

Fea Vinegia tremar l’acqua, e la terra,

Per dar dalla Città perpetuo bando

All’ozio, che l’umana gloria atterra,Andarono i Politici inventando

Un giuoco, il quale avea forma di guerra,

In cui spesso operando i loro petti,

Empivan di coraggio i Giovanetti.

Alle eroiche prerogative da per tutto decantate di Sua Ecc.a il Sig.e Co. Giovan Battista Fioravanti di Salò diamo occasione di accogliere una riverente offerta dell’amor nostro, giache saprà che del 1692 qui Gio. Cagnolini stampò un bel discorso sopra la origine e regole di questo giuoco.

Grevembroch (1981), vol. 1, p. 87.

Related articles

- Gli abiti de veneziani — by Giovanni Grevembroch

- Ball games in Venice

- The game of Calcio

- The game of Pallone

Related images

- Nobile alla Rachetta — Grevembroch 1-94

- Nobile al Giuoco del Pallone — Grevembroch 1-89

- Giuoco del calzo — Habiti d’huomeni et donne venetiane — 35

Venetian Stories

Bibliography

- Grevembroch, Giovanni. Gli abiti de veneziani di quasi ogni eta con diligenza raccolti e dipinti nel secolo XVIII, orig. c. 1754. Venezia, Filippi Editore, 1981. [more]

Leave a Reply