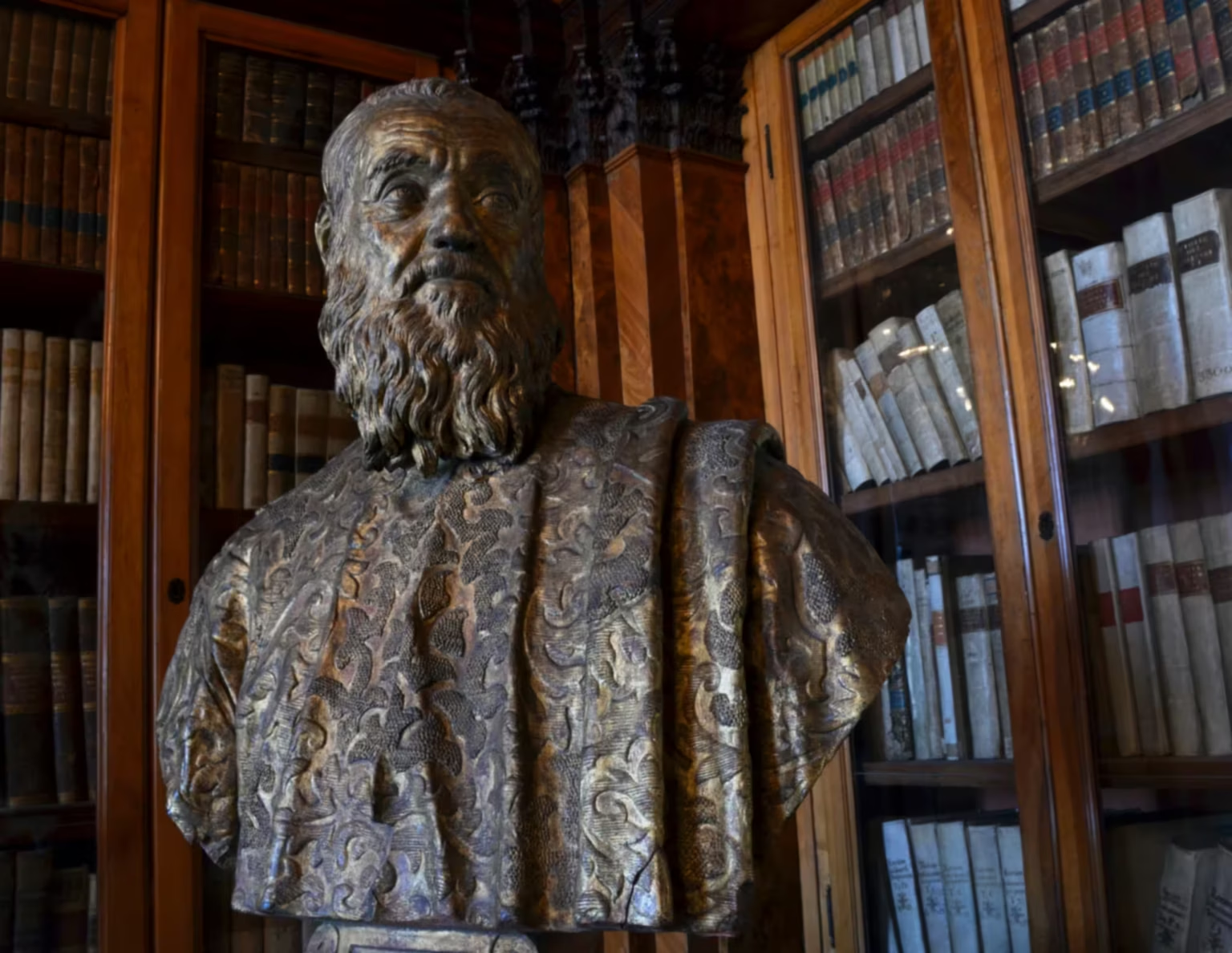

There’s a statue of a bearded man on the façade of the church of San Zulian, above the entrance.

Yet another saint, one presumes, before walking on towards the main sights at St Mark’s.

Well, no! That’s Tommaso Ravenna, astrologer, physician, patron of the arts and sciences, knighted in several countries, who in the 1500s got rich and famous selling remedies for syphilis.

Tommaso Giannotti

He was born in 1493 as Tommaso Giannotti (or Zanotti) in Ravenna to a well-off citizen family. Ravenna wasn’t his real name, but simply a reference to his birthplace.

Little is known of his youth, but in 1510, he was studying philosophy and medicine in Bologna, and in 1513 he defended his dissertation successfully. He started teaching, probably astrology, at the university immediately after, in a position reserved for brilliant but poor scholars.

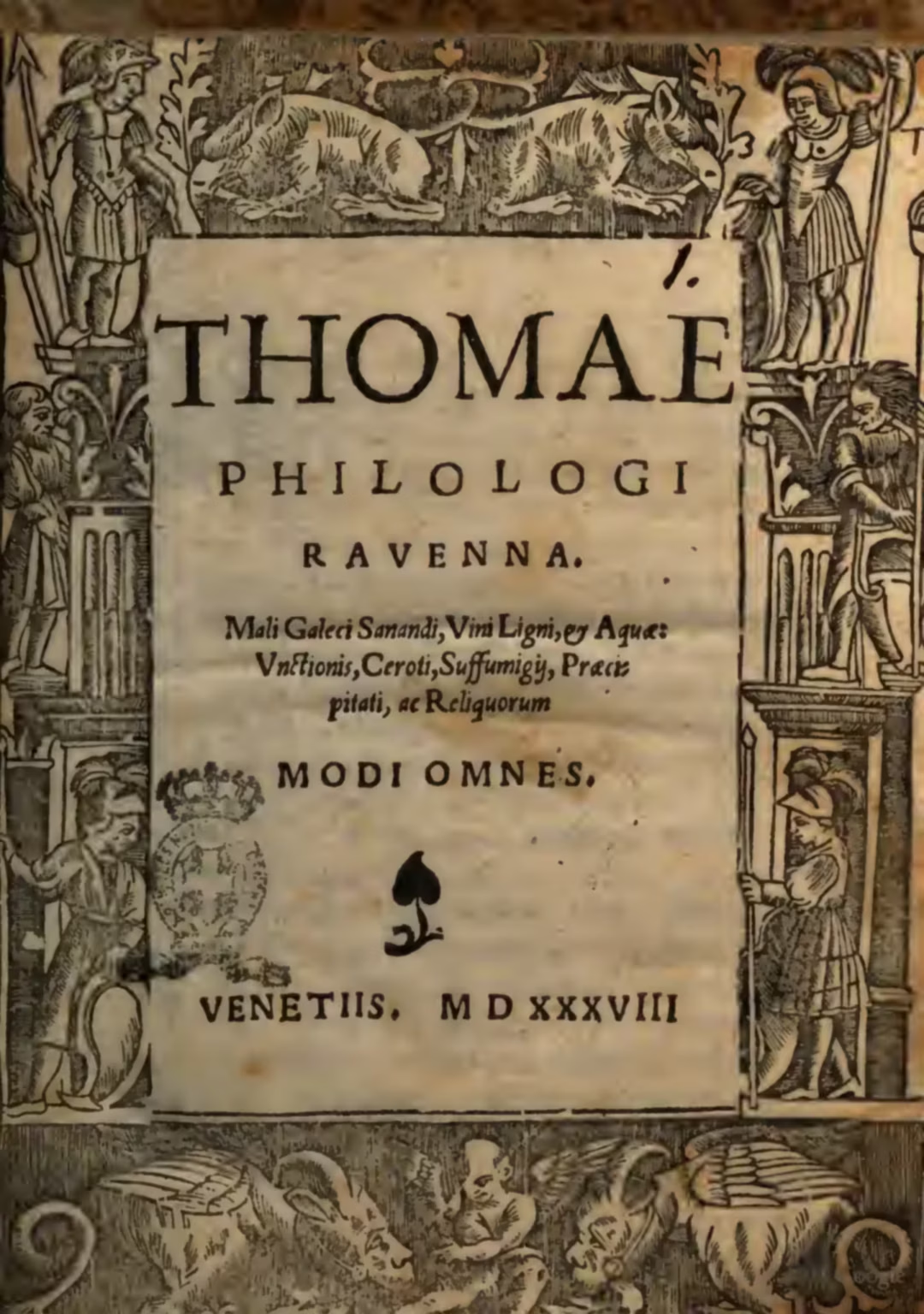

He used the academic title, which he acquired in Bologna — Philologus — for the rest of his life.

The earliest publications to his name are all astrological in nature, but there’s nothing odd in that. Astrology was, at the time, an entirely respectable scholarly endeavour.

Around 1516, Giannotti went to Rome as doctor for cardinal Domenico Grimani, whom he might have got to know in Bologna.

Cardinal Grimani, from the Santa Fosca branch of the ancient Grimani noble family in Venice, would open many doors for Tommaso Giannotti.

Domenico Grimani was the oldest son of Antonio Grimani, who was very wealthy and a central person in Venetian politics, despite some mishaps during the Second Ottoman-Venetian war in 1499, which led to a short exile in Rome with his son, the cardinal. Antonio Grimani was doge 1521–1523.

Domenico was Patriarch of Aquileia until 1517, when he ceded that position to his nephew.

His collection of books and manuscripts was later bequeathed to the Republic of Venice, and became the start of the Biblioteca Marciana, a kind of national library for the Venetian Republic.

Tommaso Giannotti only spent a year or two in Rome, before going to Venice with his lord and patron. Within a very short time, he was teaching at the University of Padua, initially sophism, but he quickly moved to astrology and mathematics.

Tommaso Rangoni

He left Padua suddenly, for a position as astrologer and physician to Count Guido Rangoni, an aristocrat from the Duchy of Modena, and condottiero in the service of the Papal State.

Giannotti was one of the astrologers, who foresaw a giant flooding for 1524, due to a conjunction of several planets in the sign of Pisces. The flooding didn’t materialise, and Rangoni and Giannotti, who with many others had sought refuge in the mountains, were sorely ridiculed in the carnival in Modena that year.

Despite the flood debacle, Giannotti remained in the service of Rangoni until 1532, and their relationship was so close, that Rangoni gave Giannotti permission to use his surname. He signed himself as “Thoma Rangone” as early as 1527.

Count Rangoni spent a period in Venice sometimes around 1530, still with Giannotti in his employ, but when he departed in 1532 for Hungary to fight the Ottoman Turks, his astrologer remained in Venice.

Tommaso Ravenna

Tommaso Rangoni, as he now called himself, would stay in Venice until his death, over four decades later. Here, he was mostly known as Tommaso Ravenna, after his native city, even though that was never his name.

He had published much over the years while in the service of Grimani and Rangoni, mostly on astrology and forecasts, but he gradually shifted towards medicine.

Once in Venice, he produced numerous booklets and pamphlets, on matters of medicine, and especially on syphilis and advice for longevity, both of which quite profitably.

As his writings circulated in all of Europe, and wealthy and powerful patients sought his advice, his fame and wealth grew.

Charity and patronage

From the early 1550s, Ravenna started sponsoring arts and sciences, and engaged in charity.

In 1552, he bought a palace in Padua, where he founded a college for poor students, especially from his native Ravenna. When the building burned in 1560, Ravenna had it rebuilt by Sansovino. This college existed until the end of the republic.

In 1562, he founded a charity, which each year on the day of San Giminiano offered a dowry of twenty ducats to six poor girls. In return for this, doge Girolamo Priuli appointed him Cavaliere di San Marco, the highest honorific the Republic of Venice could bestow on non-nobles.

The same year, he was elected for a one-year term as guardiano grando of the Scuola Grande di San Marco. In that position, paid out of his own purse, he commissioned three painting for the school by Tintoretto. The paintings, when delivered, had Ravenna depicted prominently, and they were returned to the artist by the then leadership of the school. Later, they returned to the school unmodified.1

As that last episode illustrates, as Ravenna’s fame and wealth grew, so did his ego.

In his charitable activities around the church of San Geminiano, which faced the Piazza San Marco, he tried to have a bust of himself placed on the façade, overlooking the square. The request was denied, as nobody, not even the most accomplished doges, had their statues in or on the square.2

Likewise, he wanted his bust on the façade of the Scuola Grande di San Marco, which the membership of the school also turned down.

People were, by then, probably a bit wary of his incessant self-promotion, because of the church of San Zulian.

San Zulian

In the mid-1500s, the medieval church of San Zulian was in a sorry state, and at risk of collapse.

Unusually, the church was a chiesa palatina, that it, it was under the jurisdiction of the Venetian republic, not the Catholic Church. It was managed by the primicerio of the Basilica di San Marco.

In 1553, Ravenna offered to pay for a new façade for the church, designed by his friend Sansovino, to the price of 1,000 ducats.

In comparison, the original amount allocated for the construction, from scratch, of the Redentore church in 1576, was 10,000 ducats. The Redentore, as it was built, probably cost twice that, but it still shows that the offer of Ravenna was substantial. It was not a small amount of money.

The condition of the offer was, that a funerary monument commemorating Ravenna would adorn the front of the church.

The Venetian Senate gave its consent, provided the statue was sitting, and legal papers were drawn up between the parish and Ravenna.

Consequently, the entire façade is a monument to Tommaso Philologus Ravenna. Not just the statue, but every other element, including all the inscriptions present, are about him and him alone.

Collapse

During the work building the façade, the roof of the old church collapsed.

More money had to be found, several times the amount allocated to the front.

Ravenna offered a part, on the condition that others from the parish did the same. Since the parish occupied part of the mercerie — streets with the shops of the wealthy merchants of brocade, damask and taffeta — this was not unreasonable.

The needed amount was not reached, but the reconstruction of the church started anyway. However, this time the paperwork was quite explicit, that Ravenna could be buried inside, in front of the main altar, but without any inscriptions or statues of him anywhere inside the church.

The façade

The façade is designed by Sansovino, while the bronze statue of Ravenna is by Alessandro Vittoria, a student of Sansovino.

The statue sits on top of a symbolic sarcophagus, surrounded by the symbols of what Ravenna wanted to be remembered for his books, his knowledge, his medicines, his fame.

In particular, the branches in his hand are of smilax aspera and of lignum vitae, which were both used for medicinal purposes, also against syphilis.

There are several inscriptions on the façade.

The central inscription is in Latin:

THOMAS PHILOLOGVS RAVENNAS

PHYSICVS AERE HONESTIS LABORIBVS

PARTO · AEDES PRIMVM PADVAE

VIRTVTI · POST HAS SENATVS

PERMISSV PIETATI ERIGI

FECIT · ILLAS ANIMI · HAS ETIAM

CORPORIS MONVMENTVM

And to the left of the statue:

ANNO MUNDI M VI·DCC LIIII NONIS OCTOBRIS

And to the right:

IESV CHRISTI M·D·LIIII VRBIS M·C·XXXIIII

Which all together translates as:

Thomas Philologist of Ravenna, doctor, with money procured by honest efforts, who first built a temple to excellence in Padua, then, with permission of the Senate, this of devotion: one monument of the spirit, the other also of the body. Year of the world 6754, October 7, of Jesus Christ 1554, of the city 1134.

The Greek inscription on the right side:

ΘΩ ΜΑΣ ΦΙΛΟΛΟΓΟΣ Ο ΡΑΟΥΕΝΝΑΤΗΣ

Ο ΤΑ ΤΗΣ ΟΙΚΟΥΜΕΝΗΣ

ΓΥΜΝΑΣΙΑ ΒΟΝΩΝΙΑΣ

ΡΩΜΗΣ ΠΑΤΑΟΥΙΟΥ ΣΟΦΙΑ

ΛΑΜΠΡΥΝΑΣ ΑΝΗΓΕΙΡΕΝ

ΕΤΕΙ ΑΠΟ ΚΤΙΣΕΩΣ

ΚΟΣΜΟΥ·Ζ·Ξ·Β

Translated:3

Thomas Philologus of Ravenna, who with his doctrine gave lustre to the university of Bologna, Rome and Padua, built in the year 7062 from the creation of the world

The Hebrew text to the left reads:

טומאז פלולוגוס מראוינה אשר חבר

ספרים הרבה בחכמות שונות וגם מצא

דרך לחאריך חיי האדם יותר ממאה

ועשרים שנה * ובנה משלו בשנת

הבריאה ה אלפים שטו

Translated:

Thomas Philologus of Ravenna, who composed many books on various sciences, and also found a way to make man’s life continue for more than one hundred and twenty years – built at his own expense in the year of creation 5315.

The End

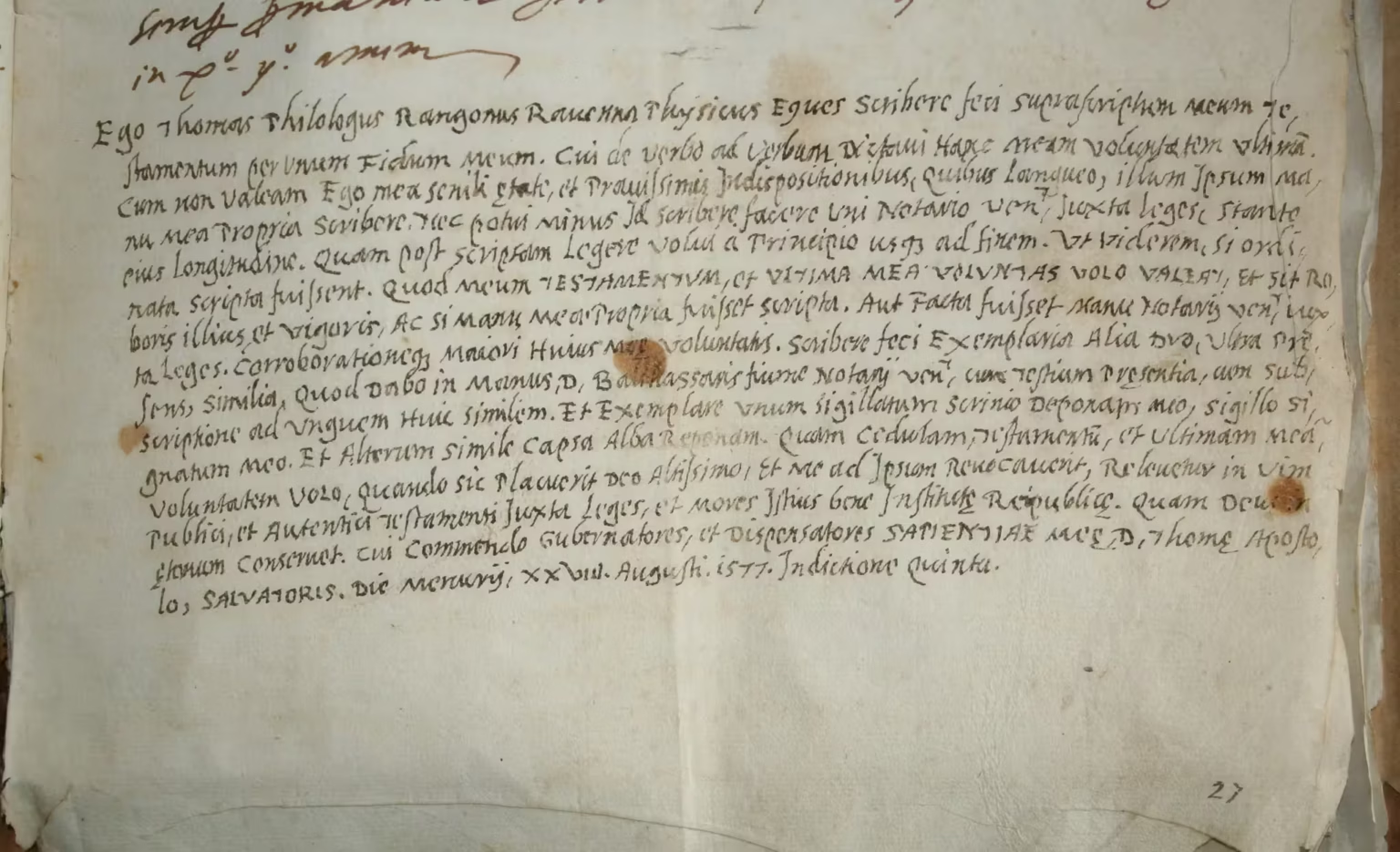

Thomas Giannotti Rangoni Ravenna died on September 10th, 1577.

He had survived the plague of 1575–1577, according to Rocco Benedetti, who wrote an eyewitness account of the epidemic, by staying in his home for the entire period.

In his last will and testament, he had made elaborate provisions for his funeral, which were grander than the pomp organised for most doges. He was carried through most of the city, in a procession with hundreds of participants, with many of his books carried in display, and a model of the church, too.

He was, as agreed, buried inside the church of San Zulian, but without a name on the slab covering the tomb.

When, in 1823, it was decided to disinter all the burials inside the church, his bones were taken to the ossuary on the lagoon island of Sant’Ariano, north of Torcello.

His statue, paid for by selling remedies for syphilis, is still there, above the entrance.

Notes

- Two of these paintings are now in the Galleria dell’Accademia in Venice, and one in the Fondazione Brera in Milan, after they were looted by the French in 1807. ↩︎

- A similar request by Bartolomeo Colleoni in 1475 had been denied, too. ↩︎

- Transcriptions and translations of the Greek and Hebrew inscriptions are from Zorzi (2012). Any errors in the transcriptions here are entirely my fault, as I have little experience with those alphabets. ↩︎

Related articles

Bibliography

- Bacchelli, Franco. GIANNOTTI RANGONI, Tommaso in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani – Volume 54. Treccani, 2000. 🔗

- Sapienza, Valentina. La chiesa di San Zulian a Venezia nel Cinquecento. Publications de l’École française de Rome, 2018. 🔗

- Tassini, Giuseppe. Curiosità Veneziane ovvero Origini delle denominazioni stradali di Venezia. 1863. [more] 🔗

- Weddigen, Erasmus. Thomas Philologus Ravennas in Saggi e Memorie di storia dell’arte, Vol. 9 (1974), pp. 7, 9-76, 149-172. Casa Editrice Leo S. Olschki s.r.l., 1974. 🔗

- Zorzi, Nicolò. L’iscrizione trilingue di Tommaso Rangoni sulla fac- ciata della chiesa di San Zulian a Venezia (1554) in Quaderni per la Storia dell’Università di Padova, 45, p. 107-138. Editrice Antenore S.r.l., Roma-Padova., 2012.

Leave a Reply