The Venetian nobility was formally egalitarian, but in practice not so much.

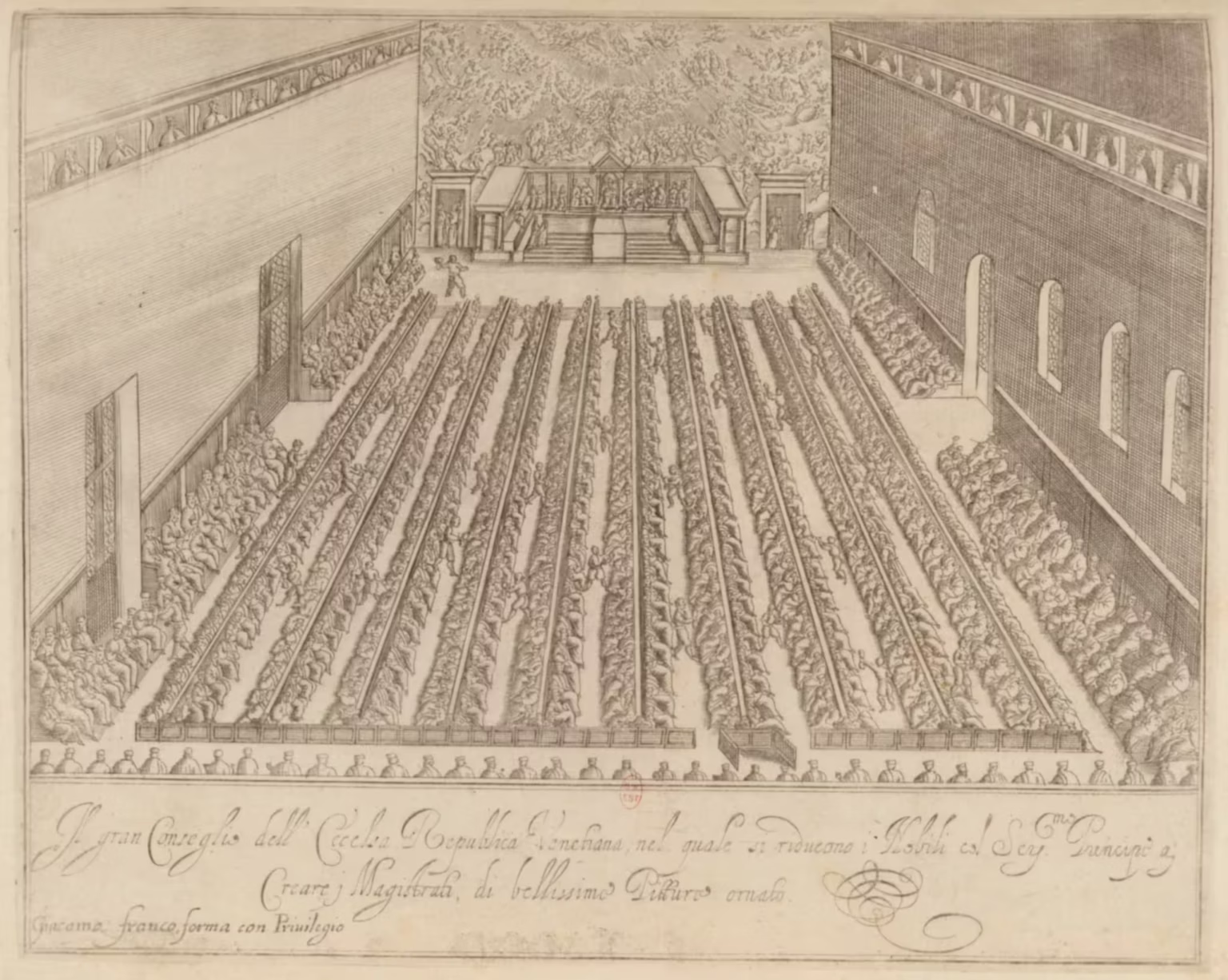

The aristocracy was in charge of the Republic of Venice for most of its history, and in particular after the “Locking of the Council” in 1297. Membership of the Greater Council was then made hereditary, and limited to members of the nobility.

The nobles never more than a few percent of the population, but they always dominated the republic, and after 1297, they were the republic.

An egalitarian aristocracy

In principle, all members of the Venetian nobility were equals, and they had, again in principle, access to the same privileges, positions of power and titles.

All noblemen had the title of Nobil Homo, the more Latin form, shortened N.H., or Nobiluomo, more Venetian, shortened N.U. For the women, the title was Nobildonna.

Later, other forms, such as Zentilomo (Venetian), Gentiluomo (later, more Italianised) — which surprisingly means Gentleman — also became common usage. Likewise, Patrizio, meaning Patrician.

In Venice, there were no such titles as “Duke of This” or “Count of That”. They were, simply, “Nobles”, and their status wasn’t associated with any specific locality or property.

In Western Europe, where a feudal system developed, the status of “noble” derived from ownership of agricultural estates, as land was the predominant means of creation of wealth. Consequently, their titles were associated with and usually followed the ownership of landed properties.

The Republic of Venice was, for the first many centuries, limited to territories in the marshes of the Venetian lagoons. This was the Dogado of the Venetians.

In the lagoons, there simply wasn’t sufficient agricultural land to form the basis for an economic and social hierarchy predicated on ownership of landed properties.

The Venetian elite therefore formed within a merchant class, where monetary wealth mattered more than landed estates.

This is probably the origin of the egalitarian form of the Venetian nobility.

Inequalities between peers

However, even in the earlier periods, there were nevertheless nobles who were, or perceived themselves to be, more equal than the others, even if their legal status was the same.

From the earliest times a social hierarchy existed based on the age of the dynasties (called case, houses), but it was only that, a social hierarchy within the nobility. A family wasn’t necessarily more influential just because it was older.

In later times, the important divide was based on family wealth.

Many important positions within the Republic of Venice incurred substantial expenses on the office holder, which excluded members of lesser affluent families from seeking such roles. This created over time a de fact stratification of the nobility.

Case Vecchie — the old houses

The oldest noble houses in Venice are shrouded in myths, as their origins coincide with the origins of the Venetian state itself.

Many legends appeared over time about the earliest noble families, and how the later nobility could be their descendants.

Early chronicles indicate twelve named families as the electors of the first doge in 697. This is almost certainly mythological, but the resulting terminology persisted. They’re called the apostolic families.

Another four families of ancient origins were called the evangelic families.

It is traditional to group all the noble families attested in Venice before the year 800 as the case vecchie — the old houses.

See the complete list of the case vecchie here.

A good deal of these families became extinct over the centuries, but others continued until the end of the Republic, and beyond.

The members of the case vecchie were called longhi — long — as in a long family line.

Case Nuove — the new houses

The families accepted as nobles from 800 until 1297, when access to the Greater Council was ‘locked’, are called the case nuove — the new houses — and their members are curti — short.

A good dozen families were accepted into the Greater Council shortly after 1297, especially after the Bajamonte Tiepolo conspiracy in 1310, and they are considered case nuove as well.

All in all, the case nuove were around 150 families.

The curti managed to dominate the longhi in Venetian politics for much of the 1400s and 1500s, when almost all the doges were “short”.

The fifteen or sixteen families of the case nuove who had a member elected doge, are also referred to as case ducali — the ducal houses.

Case Nuovissime — the very new houses

In the War of Chioggia (1379–1381) the Venetian state almost succumbed, and all possible resources were mobilised for the war effort. After the war, based on their contributions, thirty families were granted the status of “nobles.”

They are normally called the case nuovissime — the very new houses.

Some of them had the same name of already existing noble families. Over the centuries, most families split up in different branches, all with the same family name, and very often some branches of a family were nobles, while others were citizens.

There is, in fact, a huge overlap of the lists of known noble families and known citizen families. A family name alone wasn’t always enough to communicate the status of the family.

Distinct families with the same name were often assigned informal nicknames. The Gradenigo di Santa Giustina lived in the parish of Santa Giustina, while other Gradenigo lived elsewhere in Venice. The Contarini della Porta di Ferro had a particular cast iron gate on the canal side door of their palace, while the Contarini del Bovolo had a unique spiral staircase, which is still a tourist attraction today.

Honorary nobility

The Republic of Venice sometimes conferred nobility on foreign aristocratic families, as a title of honour, or for services to the republic. Most often, these families never resided in Venice, and didn’t take part in Venetian matters of state.

Between two and three dozen such cases are known.

Among others, the Bentivoglio family from Bologna was granted this status in the late 1400s. The daughter of Bianca Cappello, Pellegrina Bonaventuri, married into this family.

Some of these families were local nobility from the subject cities in the Venetian mainland dominions. Such a case is the Colleoni family from Bergamo. The honour only lasted the lifetime of Bartolomeo Colleoni, who is, to this day, remembered with a very rare statue in Venice.

Case fatte per soldo — houses made by money

During the 1600s and 1700s, the period of relative decline in Venice, the nobility shrank as old noble families became extinct.

All it took for a family line to perish, is for the last male to have no legitimate heir. Since the title was not tied to a specific property, as in a feudal system, it didn’t pass with the land the title was associated with, to some cadet branch. There was no land. Instead, the line ended.

The Republic of Venice fought some protracted and costly wars against the Ottoman Turks in the 1600s and early 1700s, over the Greek islands of Candia (Crete today) and Morea (the Peloponnese).

To replenish both coffers of the Republic’s and the Greater Council, new families were admitted to the nobility for payment; hence the name give to this new group: case fatte per soldo — houses made by money.

The price was 100,000 ducats, which would be enough to buy a couple, or more, of palaces on the Grand Canal. The families which entered were therefore generally quite wealthy.

All in all, we’re talking of about 75 families for the War of Candia, and another almost fifty for the War of Morea.

Few of these families distinguished themselves in the republic, but we do find the Manin family in the first group, whence came the last doge of the Republic, Ludovico Manin. In the second group was the Rezzonico family, whose magnificent palace on the Grand Canal is now a civic museum.

Money matters

While some status might be derived from the age of a lineage, in practical political matters they weren’t that important. The factional fights would often see families allied across these categories, and against each other within the groups.

What really mattered, was the wealth of a noble family.

Political and military positions in the Republic of Venice, even high-ranking and very influential offices, only received a symbolic pay. As nobles, it was both their duty and their privilege to carry their part of the burden of running the republic.

Office holders were therefore expected to be sufficiently wealthy to cover the related expenses.

The more central the office, the higher the expenses to keep up with the dress code, representation in general, and whatever else might follow with the dignity and status of the office.

This led to a formal classification of state offices and a subsequent information classification of the noble families into three groups: senatorial, judicial and the rest.

Senatorial offices and families

The requirement for a position in a senatorial magistracy was membership of the Senate, which became limited to those families which could afford such positions. They were the “senatorial” families, the highest stratum within the aristocracy of the late Venetian Republic.

Naturally, membership of the Senate, of the Signoria, and of the Council of Ten were limited to these houses.

Other magistracies were senatorial as well. The Magistrato alle Acque regulated use of water resources in the lagoon. The Magistrato de la Biastema oversaw taverns, gambling, prostitution and fought blasphemy and vice in general, while the Magistrato alle pompe regulated ostentatious spending. The Jewish population of Venice was managed by the Tre Inquisitori sopra gli Ebrei, while the university was checked by the Riformatori dello Studio di Padova. On the more economic side, the Provveditori sopra ogli levied duties and regulated the trade in (olive) oil.

Judicial offices and families

The positions in the many courts and tribunals of the Republic of Venice were less costly to occupy, and therefore accessible to noble families with fewer means.

These were the judicial offices and therefore the judicial families.

The highest aspirations for members of such families were the Quarantia, the court of appeal for cases not involving nobles.

In terms of numbers, these were probably the most of the nobility, but also the least noticed.

An alternative career path was in the navy, as “Nobles in the Galleys”.

Domenico Pizzamano, who was the commander of the Forte di Sant’Andrea in April 1797, when three French ships tried to enter the lagoon, is a good example of such a mid-level nobleman.

The Barnabotti

The barnabotti were noble families so poor, they could only afford to hold the lowest positions in the republic. Many were so destitute they couldn’t feed their families or pay their rent.

The name barnabotti refers to the area around San Barnaba, which was one of the cheapest areas in Venice to live in.

There are two good reasons for why there were poor families in the ruling elite of the Republic of Venice.

The “Locking of the Council” in 1297 had made it very difficult for newly rich citizen families to enter the aristocracy, but if the door is locked, figuratively speaking, so nobody could enter, nobody could leave either.

Therefore, families which were rich and eligible in 1297, but whose fortunes had waned in the following centuries, were nobles and couldn’t escape the related duties and obligations. A person’s status was determined by their birth, and it worked both ways.

A reason for some noble families falling into poverty, was some of those existential — and costly — wars, which Venice fought over many centuries.

The War of Chioggia (1379–1381), with its forced loads and extraordinary taxation, in a situation where normal business was all but impossible, broke the bank for some noble families, who never recovered.

Likewise during the League of Cambrai (1508–1516), the War of Candia (1645–1669) and the War of Morea (1684–1699).

In such cases, we’re talking about families, who had fallen on hard times, not because of incompetence or stupidity, but in service of the republic.

The rest of the Venetian aristocracy responded with a bit of class solidarity. Some allowances and privileges were granted to the barnabotti, and they could occupy some of the lower positions in the hierarchy of the republic, where the pay was more than the cost of holding office.

Also, they still had a vote in the Maggior Consiglio, and often the votes of the poor nobles were for sale in the Broglio — a fruit garden which existed near the Doge’s Palace.

Illustrations

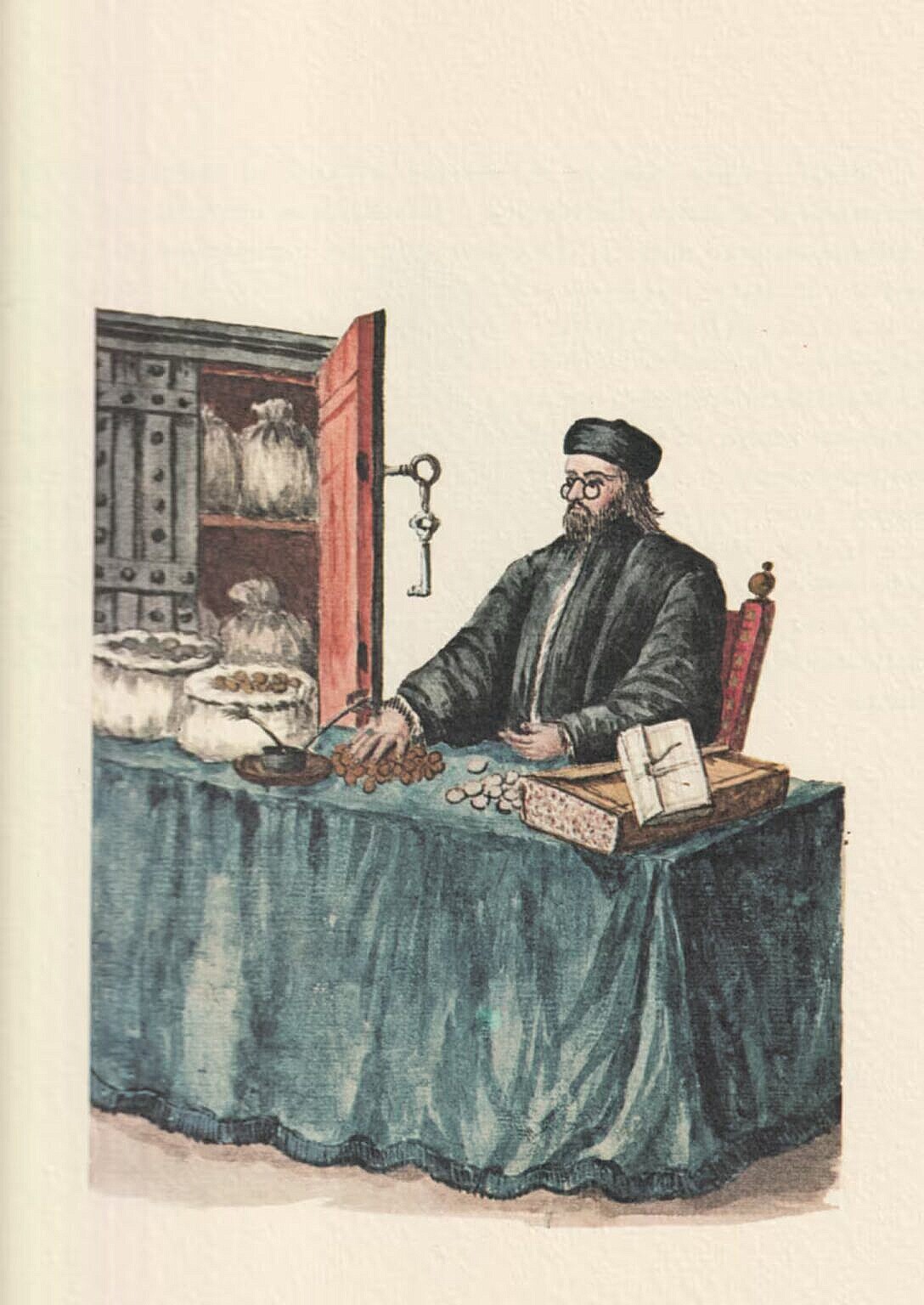

The watercolours used above are all by Giovanni Grevembroch, from his magnificent Gli abiti de veneziani, mid-1700s.

The title image is Nobles at the Café — Grevembroch 1-096.

Related articles

Related sources

Bibliography

- Boerio, Giuseppe. Dizionario del dialetto veneziano. Venezia : coi tipi di Andrea Santini e figlio, 1829. [more] 🔗

- Chojnacki, Stanley. La formazione della nobiltà dopo la Serrata in Storia di Venezia. Treccani, 1997. 🔗

- Da Mosto, Andrea. L'Archivio di Stato di Venezia : indice generale, storico, descrittivo ed analitico in Bibliothèque des Annales Institutorum, 5. Roma : Biblioteca d'arte, 1937. [more]

- Leader, John Temple. Libro dei nobili veneti / ora per la prima volta messo in luce. Firenze Tipografia di G. Barbèra, 1866. [more]

Leave a Reply