The Venetians played ball games of various kinds. The game of Calcio is the one sounds most modern, but it wasn’t exactly like it’s played today. Far from it, in fact.

In Italian, modern football is called calcio, so for Italian speakers that’s the first association. It is therefore tempting to think of it as a kind of ancient football, but it probably resembled rugby more, as the players — at least in some versions of the game — could pick up the ball with their hands.

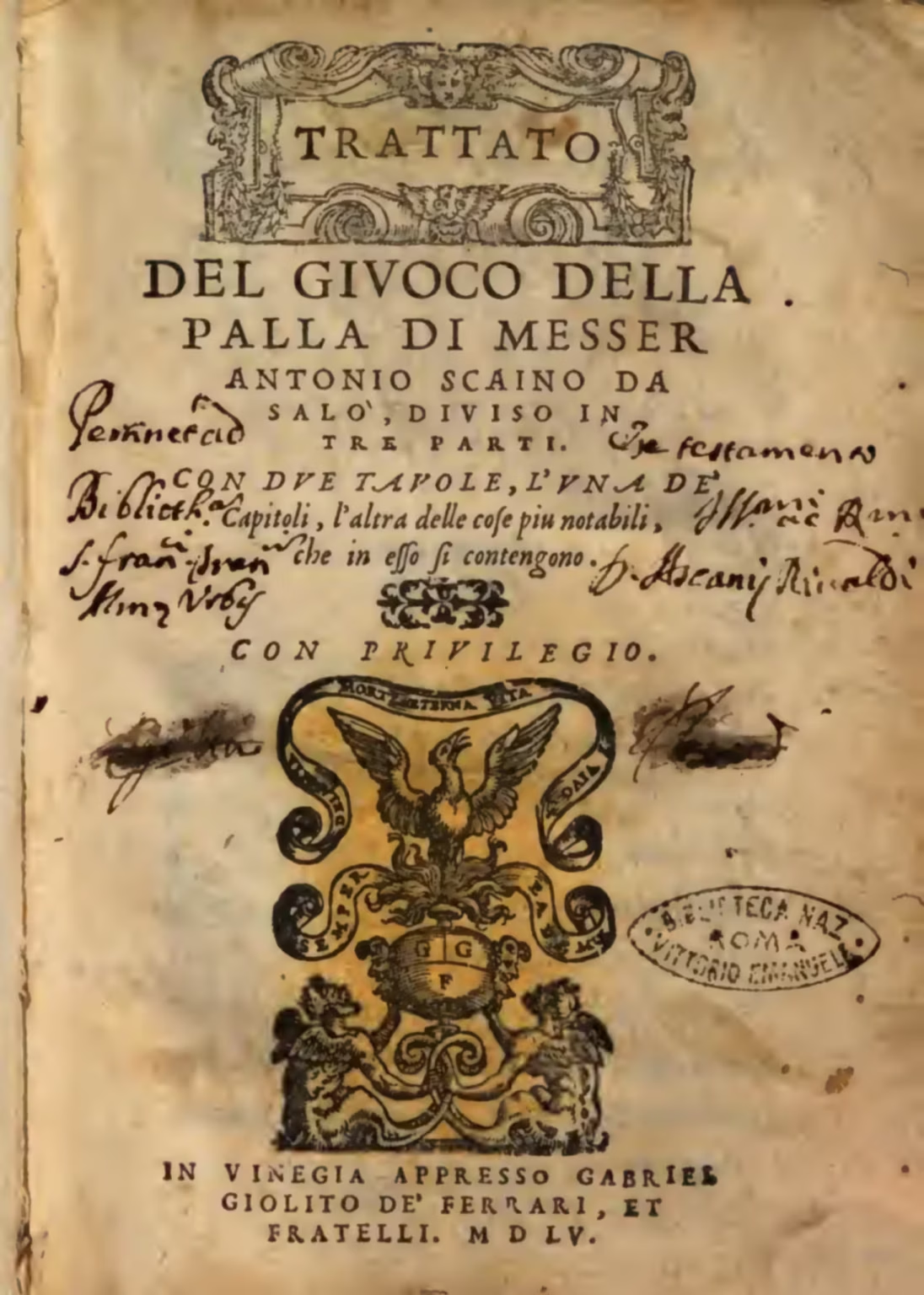

Our main source for early modern calcio is Antonio Scaino, in his Treatise on the game of ball from 1555.

Calcio was not his favourite ball game. He only discussed it late in this treatise, and he emphasised the scarcity of rules:

This game of calcio in as much as it is not ordered with the same artifice as one finds in the other ball games, it is nonetheless a very gracious game, and it gives mostly the spectators great pleasure, in that it more than any other, appears almost as an image of a real battle, in which very often, here and there, the players are thrown forcefully to the ground, and in being the game in which, more than in all the other ball games, one perceives the valour of a good runner, and of those who are adept at fighting, and powerfully built.

Scaino (1555), p. 286.

It doesn’t sound much like association football, but much more like rugby, but even more physical and violent.

The playing field

The requirements for a playing field were not very specific. Scaino wrote:

… a space so large that a stone thrown by a very strong arm, from one end cannot reach the opposite end, in width almost half that, and if there are walls on the sides, it’ll be very suitable …

ibid., p. 282.

There was a fence around the field, and two gates at the extremities:

… only at both the extreme ends, according to the length of the fence, a certain area is circumscribed, within which those, who want to be victors of the battle, have to send the ball, by agreement, each on the side of the others.

ibid., p. 282–283.

So it is rather rudimentary. A playing field, surrounded by a fence, with two scoring areas at either end.

The teams

There were no rules about team size. Each side could be made up of as many as the playing fields could accommodate. Scaino continued:

… the best suited field is, I believe, found in the arena of Padua, where the students during Lent, with huge participation, are wont to exercise this battle, which you can do twenty, thirty or forty persons on each side, or ever larger numbers, according to the size of the place and the valour of the players.

ibid., p. 282.

Antonio Scaino had studied in Padua, so even if he didn’t play the game himself, he must have seen the fights.

The ball

The ball used was of leather, and inflated:

Thus, this game is played with a ball of wind, weighing ten ounces, with a diameter of seven inches, much softer and squashier than the fist ball …

ibid., p. 282.

The ‘fist’ ball was the one used for the giuoco del pallone, which was a whole other ball game.

There were few rules about how the players could handle the ball.

Let’s give the word to Scaino again:

… each player can enter this game without any kind of armour of any sort whatsoever, as it is in his prerogative to hit the ball, with which ever part of the body he pleases, and with more body parts together, when it is in the air, after the first rebound, after the second, and all the others, and he can bash it with his feet, when it rolls on the ground, he can with one or more contacts dispatch, pick up, hold and carry it (which is a glorious fact) into the goal of the enemy, only it is forbidden to throw it with the hands, and when it happens, it becomes a skirmish …

ibid., p. 283.

Gameplay

Kick-off was exactly that, which is probably the reason for the name of the game. To start the game, the ball was placed on the ground at the centre of the field, and sent into play by a kick.

Divided the field in two equal parts, and the ball placed in the middle, the players divided in the opposing factions, with some uniform, through which in the fighting they can recognise each other, given a sign at the sound of a drum or trumpet, one of the players, who is to be first, by election or by lot, hits the ball with a kick, at which point the skirmishing immediately starts, so it is permitted for one side, as well as the other, to take the ball, hit it and send it towards the goal of the adversaries …

ibid., p. 284.

Again, I don’t think the use of words such as ‘skirmish’, ‘fighting’ and ‘battle’ are figurative.

The troops were assigned their role in the battle based on their different skills and abilities.

… each gang needs a captain, who governs the battle, and who assigns roles to the players, some of which are good runners, others physically strong to resist the onslaught of the opposition, others skilled in handling the ball, and other astute at starting skirmishes, and these will be in the front of the battle as the vanguard, behind whom the stronger players, and behind these the runners; the rearguard are the skilled and experienced ball handlers …

ibid., p. 284–285.

Goals were scored either by carrying the ball running, or by kicking the ball into the goal of the opposing team.

In particular, in this game it is convenient that those players, who are placed in front of the others, if they don’t have a good opportunity to hit the ball, leave the ball to those, who are behind them, confronting in the meantime the adversaries to prevent them from gaining more field. For the runner, who is about to run down the field with the ball in hand, some of the stronger players, and those from the vanguard, should confront the adversaries, to give him expedited and free passage, and the runner, having space and occasion, run until the goal of the enemy, but if attacked by a too large squadron, slows down and with wasting time, hits the ball, and better if with the foot than in other ways, because that blow is safer, and the one which is harder to impede.

ibid., p. 285–286.

Calcio in Venice

The Venetian knew this game.

If it was played by the students in Padua, it was played by Venetians too.

Venice never had a university of its own, so anybody who wanted to study, noble or citizen, went to Padua.

The trip by boat to Fusina, and then on horseback, took a few hours at most, while the very convenient river boats up and down the naviglio took some seven-eight hours, eating, drinking, chatting, gambling while the countryside glided past outside.

In particular, the game of calcio was played in the bersaglio at Sant’Alvise in Cannaregio during Lent. A bersaglio was a shooting ground for bows and arrows, then crossbows, and later, early artillery, the bombarde.

Gabriel Bella — c.1780s

The 1700s Venetian painter Gabriele Bella made a painting which exactly matches the description by Scaino of the game of calcio.

In this painting, we see the entire playing field from the side, with an ongoing game.

The field is elongated, but not rectangular. It is oval, delineated by a simple fence, going in a curve from goal to goat.

The goals are actual gates, like you would find on a fine house. They’re arched, with decorations on top. They’re not level with the playing field, but raised on a small dais.

The two teams are numerous, one wearing red waistcoats and matching hats, the other in black or brown. Trousers and shirts are in varying colours.

A member of the red team is running with the ball in his hands towards the gate on the right, which is blocked by a player in black. Some players, of both teams, have fallen to the ground.

Four individuals on the playing fields are not participants.

Besides each gate stands a man, wearing a red jacket and holding a long post with the flag of St Mark. Such persons are not mentioned by Scaino, but they’re probably there to adjudicate scores. In fact, the guy on the right seems to be moving, as to observe the player approaching with the ball, while the other looks perfectly relaxed.

In the centre, a bit in the back, stand two military style drummers. Scaino mentioned drummers or trumpeters, so they’re probably there to give signals for the commencement and cessation of hostilities, a bit like the whistle of modern-day football referees.

The spectators, standing along the fence, are all men, and they generally appear well clad and affluent. There might be a few casual lower-class onlookers in the corners, but this is definitely a business for ‘decent’ people.

Gariele Bella was born in 1720, and died in 1799, He wasn’t a well-known artist at the time, and apparently he wasn’t formally educated at the Academy of Fine Arts. The style of Bella is rather naive, but his paintings, like the contemporary works of Giovanni Grevembroch and Gaetano Zompini, have great documentary value, as he was meticulous in getting the details right.

Almost all surviving works of Bella, including the painting discussed above, are in the collection of the Querini-Stampalia Foundation, which is custodian of the heritage of that same Venetian noble family. The Querini-Stampalia became extinct in 1869. Bella was, most probably, a kind of house artist to the family, just like Grevembroch was to the Gradenigo family around the same time.

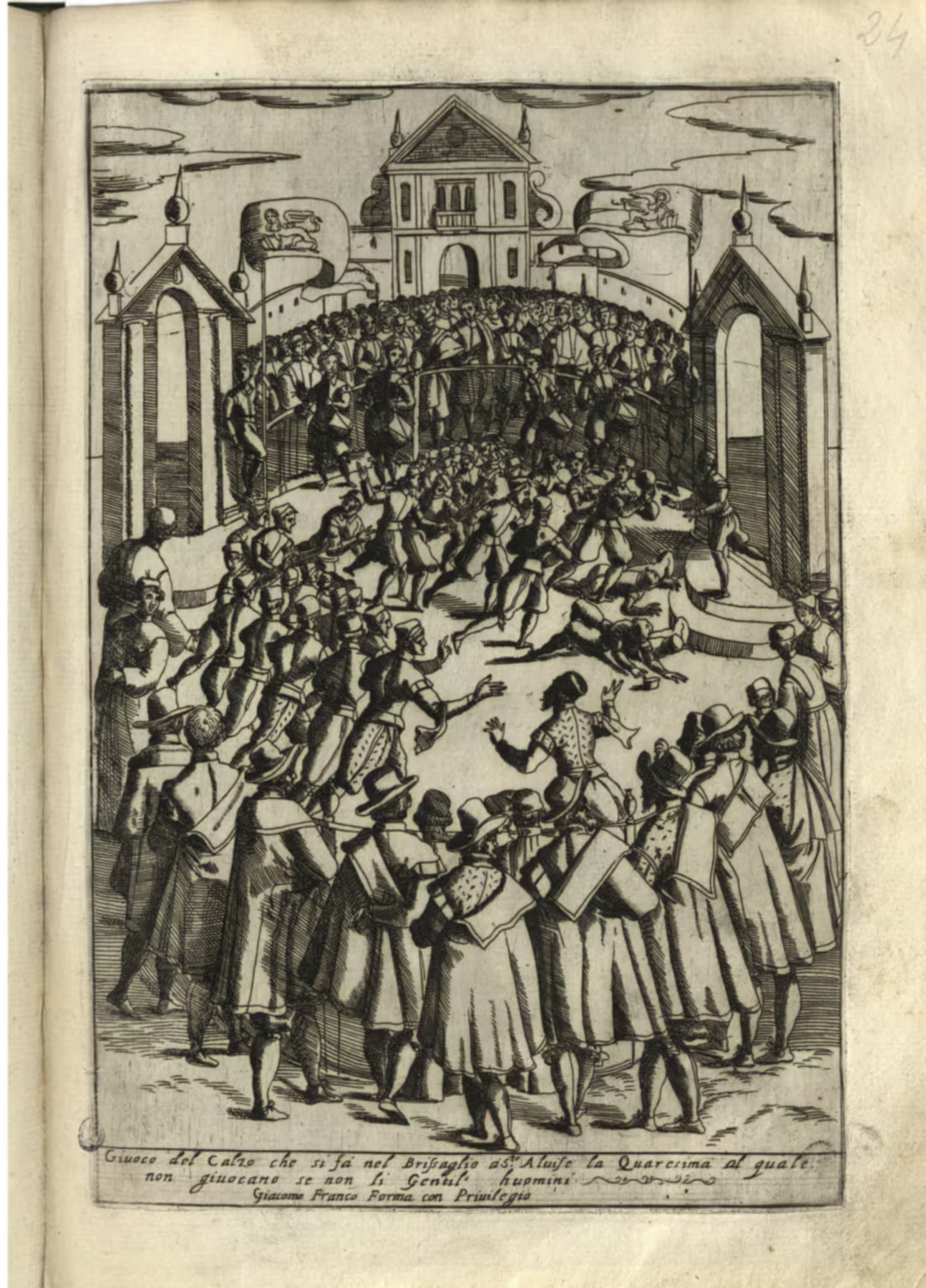

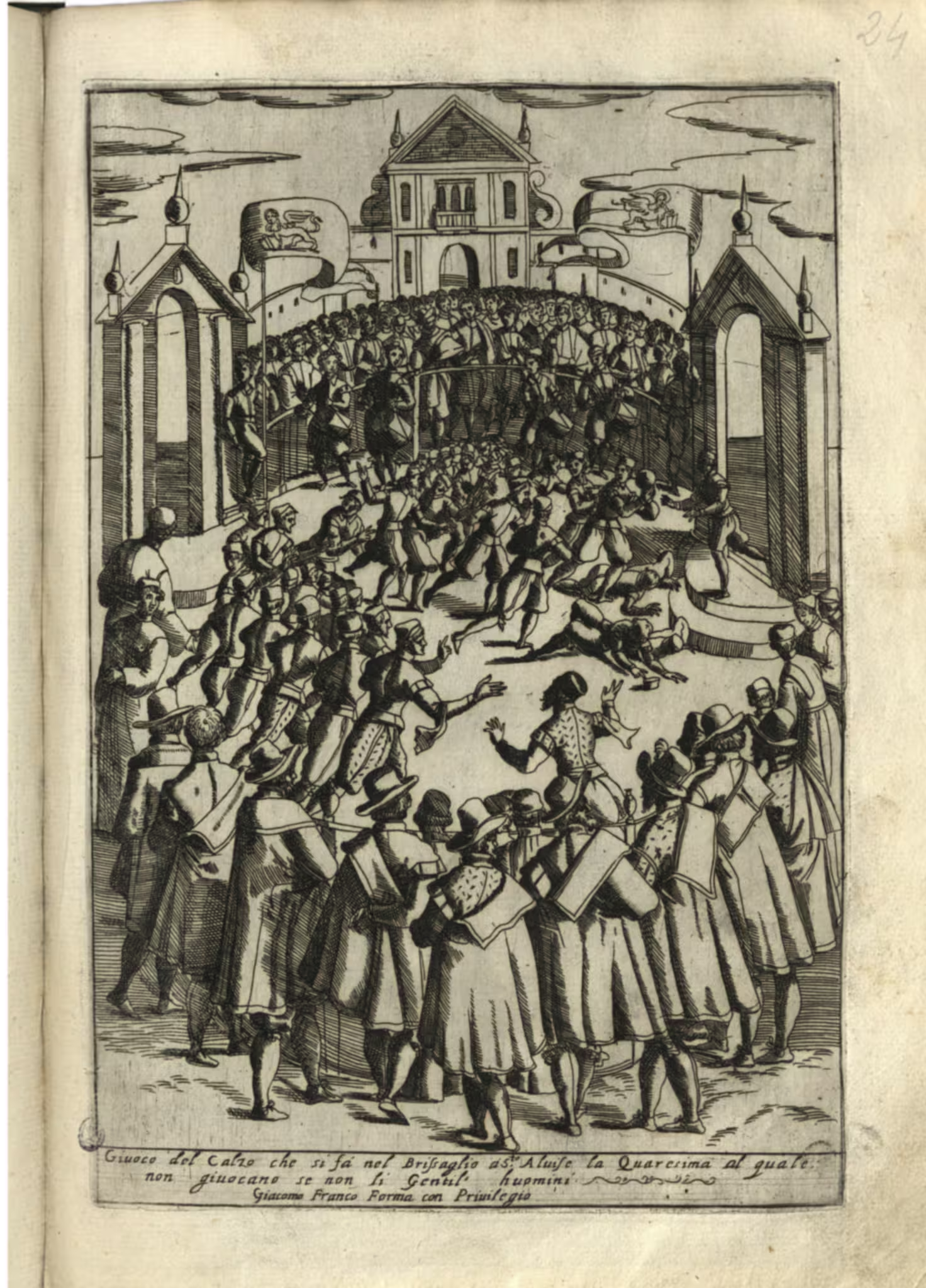

Giacomo Franco — c.1610

The painting above is no doubt heavily inspired from a print by an unknown artist from about a century earlier.

The engraving was published by Giacomo Franco in a collection of prints under the title Habiti d’huomeni et donne venetiane, which was published just around 1610 in Venice.

The caption on the print reads: Giuoco del Calzo che si fà nel Brissaglio à S.to Aluise la Quaresima al quale non giuocano se non li Gentil’ huomini.

Translated it is: “The came of Calcio which is played in the Shooting Grounds at Sant’Alvise for Lent, in which no-one plays if not Gentlemen.”

The overall scene is almost identical to the later painting by Bella, who only made minor changes to the composition and some insignificant details.

The inclusion of this print in a work on dresses, customs and ceremonies in Venice shows that the game of calcio was already well established in Venice in the early 1600s.

The Venetian must therefore, at the very least, have played the game in the late 1500s, that is, only a few decades after Scaino’s Treatise on the game of ball from 1555.

Variations of the game

There appear to have been variations of the game — or they’re different games which shared a name — because other Venetian sources indicate other, different, rules of the game.

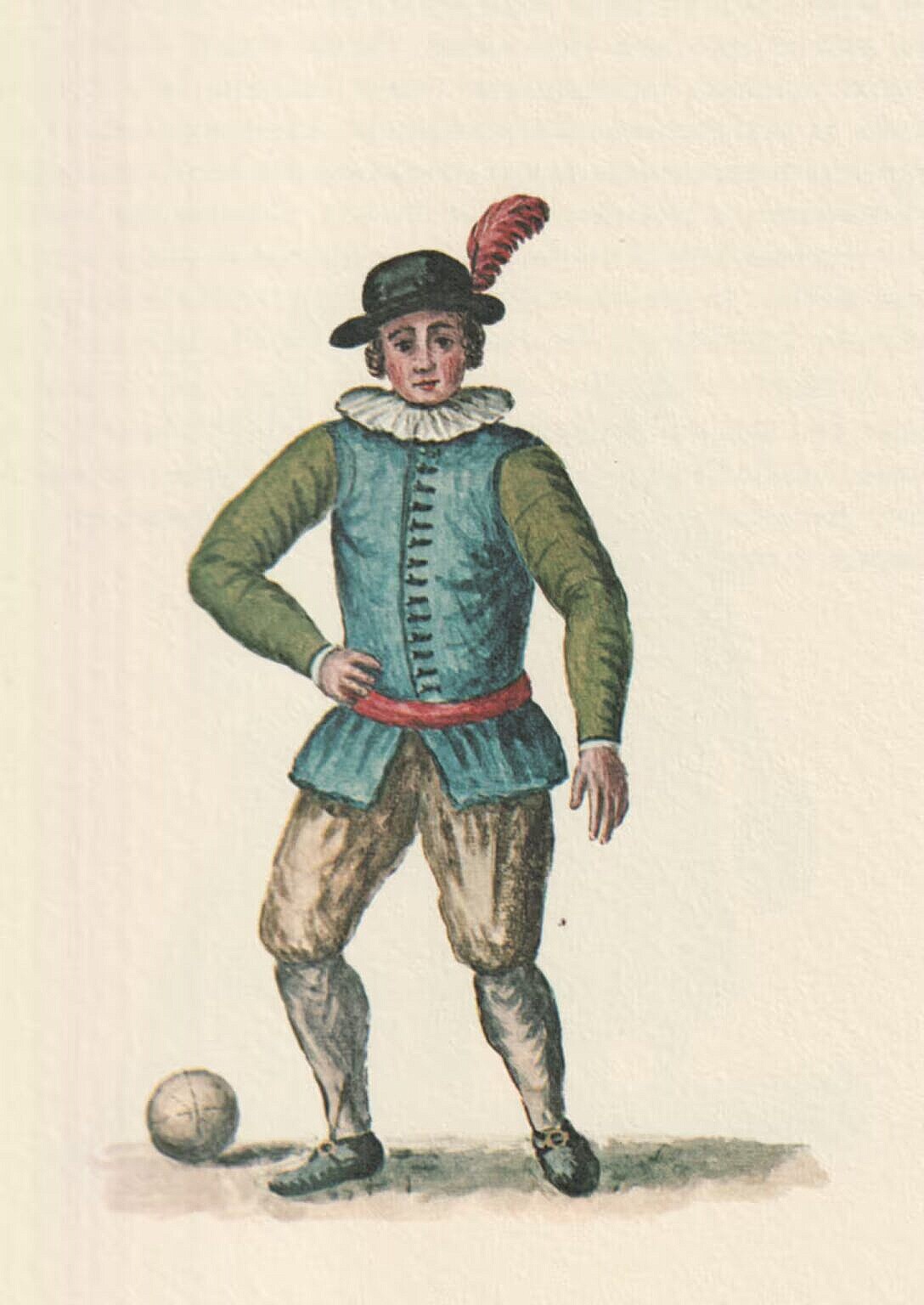

Giovanni Grevembroch, which I mentioned just a minute ago, in his work on the dresses of the Venetians from around 1750, has a watercolour of a player of calcio.

The player is dressed in a waistcoat, has a hand on his hip, and a hat with a red feather. There is a ball lying at his feet.

Grevembroch wrote this in the note to the painting:

… the Patricians introduced during the Summer, to keep themselves agile and capable of hard work, a Game that they called Calcio. They divided themselves into two numerous factions on the shooting grounds, one called that of the Mountain and the other from the Plain; and they separated the Field with one or two large Portals of Stucco or wood. The Game began from one of the sides alternately on the given signal, to pass the same Portal, in order to recover a Ball thrown from there. The Opponents skilfully opposed them, while keeping their Arms tightly joined to their Sides (as it was forbidden to use their Hands) so that with the sole strength of their Shoulders, they made a vigorous defence and the Victory, acquired in the presence of countless Spectators surrounding the Fence, was highly valued. They were dressed in undergarments with Sleeveless vests, with Caps or Hats with a red or black Feather, each according to the Uniform of their own Company.

It is evident, that this is not the same game as Scaino described, and Gabriele Bella painted.

Grevembroch is not very precise, probably because his audience knew about the game already. It is clear, though, that the players were allowed to push and shove, using their shoulders and chests, but not their hands and arms, so they cannot pick up the ball and run with it.

Another reference to a game of calcio with other rules, is Giuseppe Tassini, in his indispensable Curiosità Veneziane. On the entry for Bersaglio, which is at Sant’Alvise where the Venetian played calcio:

In the Shooting grounds of S. Alvise, during Lent, the game of Calcio was played by young patricians divided into two factions, the first positioned on this side, and the second positioned on the other side of an open door, or an arch of tables, beyond which a ball was thrown. One faction would then attempt to seize it, while the other tried to keep it, trying to push it away with their feet, and facing each other, pushing, and repelling each other with their backs and bodies only, since it was forbidden to use the arms, which had to be kept pressed against the hips. The ball being preserved or retrieved decided the victory. The wrestlers wore sleeveless, slim-fitting vests for this amusement, and covered their heads with caps or feathered hats.

This is in line with Grevembroch, but Tassini doesn’t indicate his source. He certainly knew about Grevembroch’s drawings, because they are kept in the archives of the Museo Correr, where Tassini spent half of his life.

Military training

Scaino described the game using a terminology of warlike.

He talked of battles, skirmishes, fights, enemies, victories, and he discussed different types of combatants, and their organisation and formations.

It almost sounds like the game was a kind of preparation for real war.

The game of Calcio in Venice war clearly associated with the bersagli — shooting grounds — which existed in each sestiere in the Middle Ages and later.

Grevembroch, too, saw the game as one of preparing the men for war by keeping them fit and strong.

From his notes to the watercolour of the player of calcio:

In times past, Youth practised crossbow shooting because it was mandated by law that even the nobility should go to the Lido on holidays, so that through this means they could become robust and capable of the necessities of war. The same activity was carried out for the city districts, and for this purpose, in the 14th century, boat races were also invented, teaching men to row well at the same time. … After the use of Artillery was discovered, the Bow was set aside; …

The games had few and basic rules, and combined with a large number of participants, they could probably deteriorate into mostly bloodless battles.

In Venice, some ball games were forbidden at times because people died during the matches.

They were rough games, and very physical, often violent, which was most likely all on purpose.

The game of calcio originated, unsurprisingly, as preparations for war.

Related articles

Sources

- Nobile al Giuoco del Calcio — Grevembroch 1-87

- Nobile al Giuoco del Pallone — Grevembroch 1-89

- Nobile alla Rachetta — Grevembroch 1-94

- Giuoco del calzo — Habiti d’huomeni et donne venetiane — 35

Venetian Stories

Bibliography

- Colasante, Gianfranco. Antichi giochi italiani in Enciclopedia dello Sport. Treccani, 2004. [more] 🔗

- Franco, Giacomo. Habiti d'huomeni et donne venetiane con la processione della ser.ma signoria et altri particolari cioe trionfi, feste et cerimonie publiche della nobilissima citta di Venetia. Giacomo Franco forma in Frezzaria all'insegna del sole, 1610. [more] 🔗

- Grevembroch, Giovanni. Gli abiti de veneziani di quasi ogni eta con diligenza raccolti e dipinti nel secolo XVIII, orig. c. 1754. Venezia, Filippi Editore, 1981. [more]

- Scaino, Antonio. Trattato del giuoco della palla di messer Antonio Scaino da Salò, diuiso in tre parti. Con due tauole, l'vna de' capitoli, l'altra delle cose piu notabili, che in esso si contengono. In Vinegia appresso Gabriel Giolito de' Ferrari, et fratelli, 1555. [more] 🔗

- Tassini, Giuseppe. Curiosità Veneziane ovvero Origini delle denominazioni stradali di Venezia. 1863. [more] 🔗

Localities

Updates

- August 18th,2025: Published

- September 7th, 2025: Updated with print from Franco (1610).

Leave a Reply