Daghe adosso, Nino, che i butemo a fondo!

Admiral Wilhelm VON Tegetthoff at the Battle of Lissa (1866)

—

Give it to them, Nino, that we’ll send them to the bottom!

In Venice, in the Giardini Pubblici, stands a column celebrating the victory in the naval Battle of Lissa in 1866.

At the Battle of Lissa — an island in the Croatian part of the Adriatic — the Austrians decisively defeated the Italians. They lost the war for other reasons — and subsequently ceded Venice with the rest of the Veneto to Italy.

That is how Austrian Venice became Italian.

According to legend, in the heat of battle, the Austrian admiral von Tegetthoff, shouted the order to ram the Italian flagship to his Venetian helmsman — in Venetian.

When von Tegenttoff shortly after addressed the sailors of the Austrian navy and announced the victory, the sailors responded with cries of Viva San Marco!

So, to recapitulate, we have a monument in Italian Venice, celebrating the Austrian victory over Italy at Lissa in 1866, in which the Austrian admiral spoke Venetian to his subordinates, who were clearly Venetian or Venetian speaking.

In this war between Austria and Italy, which decided the long term destiny of Venice, the Venetians were on the Austrian side. Or rather, some Venetians were on the Austrian side. Others, like the unfortunate teenager Luigi Scolari and his friends in 1859, were on the Italian side.

The future of Venice wasn’t clear. Different people saw it differently, and consequently acted differently.

A Venetian navy

When Austria took over Venice in 1815 after the Congress of Vienna they didn’t have any grand naval traditions. After all, Austria-Hungary was almost landlocked.

The Serenissima had a grand naval tradition going back a millennium. Venice also had the infrastructure to build, support and manage a navy, in the Arsenale.

The Austrians therefore built on what they had, so the early 1800s the Austrian navy was almost a Venetian navy. They continued building war ships in the Arsenale in Venice, and they continued using the Venetian system for educating navy officers.

Many of the sailors of the Austrian navy in the Mediterranean were either Venetians or from former Venetian dominions in the upper Adriatic.

The Austrians never really trusted that they could hold on to Venice in the long run, which might not surprise after all the times Venice went back and forth between France and Austria during the Napoleonic wars. They therefore built a major naval base in Pula on the Istrian peninsula on the opposite side of the Adriatic, but that was old Venetian territory too.

After the Venetian insurrection against the Austrian domination in 1848-49, the Austrians move much of the remaining naval functions from Venice to Pula, and the Venetian influence in the Austrian navy started to wane.

However, Admiral von Tegetthoff had, like most other Austrian naval officers of the time, studied at the naval college in Venice, and he had learned the Venetian language there. The Venetian language was, if not the command language of the navy, still absolutely unavoidable.

The helmsman Nino to whom he addressed the command daghe addosso was a Vincenzo Vianello from Pellestrina. Vianello was rewarded an imperial medal for his role in the battle, together with a Tomaso Penso from Chioggia.

The monument

Let’s get back to the monument in Venice, in Italy, for an Austrian victory over Italy, headed by an Austrian admiral who spoke Venetian, in a war which made Venice Italian.

The monument itself is not unusual. It is a simple white column topped by a statue of the winged goddess of Victory, holding up a laurel crown. Rostra and symbols related to the sea, such as anchors, oars and reliefs of wave patterns, adorn the trunk of the column. Four eagles sit around its base.

The Lion of St Mark on the front of the base is probably a later Italian addition.

There are three inscriptions on three sides of the base, which together tell us quite a bit about the whereabouts of this monument.

Inscription 1 – left side

On the left side of the base a short inscription in German reads: Erzherzog Ferdinand Maximilian von Östereich K. K. Viceadmiral.

Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian was the brother of the Austrian emperor, a former Viceroy of Lombardo-Veneto and at the time of the Battle of Lissa Emperor of Mexico. The Austrian flagship, which rammed and sank the Italian flagship, was the SMS Erzherzog Ferdinand Max.

The “K.K.” means Kaiserliche und Königliche — Imperial and Royal — here reference to the Kriegsmarine — the Austrian navy.

Inscription 2 – right side

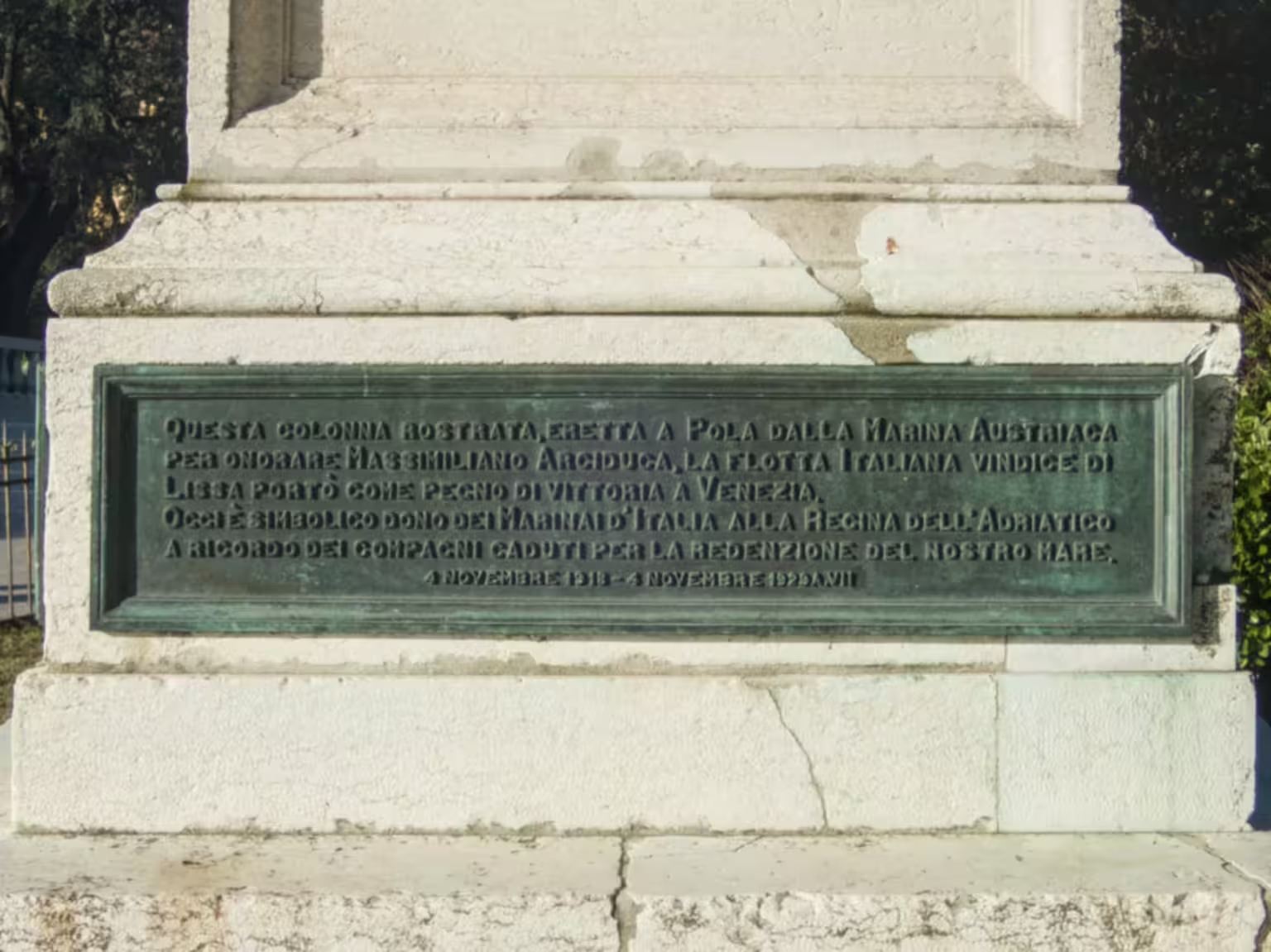

This inscription is Italian:

Questa colonna rostrata, eretta a Pola dalla Marina Austriaca per onorare Massimiliano Arciduca, la flotta italiana vindice di Lissa portò come pegno di vittoria a Venezia. Oggi è simbolico dono dei Marinai d’Italia alla Regina dell’Adriatico a ricordo dei compagni caduti per la redenzione del nostro mare. 4 novembre 1918 – 4 novembre 1928 A.VII

which in my translation becomes:

“This column with the rostra, erected in Pula by the Austrian Navy in honour of Maximilian Archduke, was taken to Venice by the Italian Navy, avenger of Lissa, as a token of victory. Today it is a symbolic gift by the Sailors of the Navy to the Queen of the Adriatic in memory of the comrades who fell for the redemption of our sea. November 4th, 1918 – November 4th, 1928, Year VII”

There’s a bit more to unpack here.

Initially, the column stood in Pula, on the Istrian peninsula in modern Croatia. It was erected 1867 honoring Archduke Maximilian, who was toppled as Emperor of Mexico that year and executed.

The Austrians made at least two monuments to von Tegentthoff and the Battle of Lissa: one is in Vienna, with a very similar column but a statue of von Tegentgoff on the top; and one in Pula, a statue of von Tegentthoff, which was moved to Graz in 1935.

Following the Great War, Italy occupied the Istrian peninsula, and in March, 1919, the took the monument down and transported it to Venice.

The date of November 4th, 1918, is a reference to the armistice between Italy and Austria-Hungary after WWI, which entered into force that day. The actual inscription on the monument was like put up ten years later, on November 4th, 1928.

That little addition at the end of the date — A.VII — is short for “Anno VII”.

This is a Fascist inscription.

The Fascist regime in Italy started counting the years from their power grab in 1921, so 1928 was “Year 7” in the Epoca Fascista — the Fascist Epoch. It is quite common to see such dates as “E.F. VII” rather than the more generic “A.VII”.

The inscription has more Fascist elements than just the way they wrote the year. Terms like “avenger”, “redemption” and “mare nostro” are common elements of the fascist vocabulary.

Claiming victimhood, and justifying violence with past sufferings, is a core tenet of Fascism, hence the need to “avenge” and for “redemption.”

The “mare nostro” — our sea — is a clear reference to the Roman mare nostrum for the entire Mediterranean Sea, and quite in line with the imperial ambitions of the Fascist regime.

Inscription 3 – front

The last — and most prominent — inscription is long and I doubt a lot of people bother to read it.

All’armata navale (ordine del giorno del XXII marzo MCMXIX)

La flotta nemica evitando costantemente la battaglia, ha riconosciuto nel modo più completo e evidente l’efficienza dell’armata e dei reparti alleati che mantennero il dominio dell’Adriatico.

Il nemico ha potuto evitare il combattimento, ma non la resa ed il disarmo della sua flotta.

Abbiamo così ottenuto la vittoria più decisa che mai fosse possibile conseguire, e la importanza di questa non è per niente la menomata dalla circostanza di non averla riportata combattendo.

Una parte di quella flotta che per quaranta mesi attendemmo invano in mare aperto giunge oggi a Venezia; e nella storica città la gloria della marina che arginò la barbarie musulmana, si accomuna alla gloria della sua naturale erede – la Marina della nuova Italia – che nello stesso mare ha arginata la minaccia di altra barbarie.

All’opera della quale la Nazione vede ora il tangibile risultato, Ammiragli, Comandanti, Ufficiali ed Equipaggi hanno portato altissimo contributo, mantenendo la flotta sempre pronta ad entrare in azione, conservando intatto, per quaranta mesi di assillante attesa, l’ardore combattivo ed il sentimento di disciplina che li animava il giorno della dichiarazione di Guerra. E per questo abbiamo vinto.

Thaon di Revel

In my translation:

To the navy (order of the day of March 22, 1919)

The enemy fleet, constantly avoiding battle, recognized in the most complete and evident way the efficiency of the Navy and the allied units that maintained the dominion of the Adriatic.

The enemy was able to avoid combat, but not the surrender and disarmament of his fleet.

We have thus obtained the most decisive victory that it was ever possible to achieve, and its importance of this is in no way diminished by the circumstance of not having won it fighting.

A part of that fleet which waited in vain for forty months on the open sea arrives in Venice today; and in the historic city the glory of the navy that stemmed Muslim barbarism is combined with the glory of its natural heir — the Navy of the new Italy – which in the same sea stemmed the threat of other barbarism.

To the effort of which the Nation now sees the tangible result, Admirals, Commanders, Officers and Crews have made a huge contribution, keeping the fleet always ready to go into action, maintaining intact, for forty months of nagging waiting, the fighting ardour and the feeling of discipline that animated them on the day of the declaration of war. And that is why we won.

Thaon di Revel

The relevance of this text to the monument frankly eludes me.

Paolo Thaon di Revel was Chief of Staff of the Italian Navy from 1917 until November 1919, and the whole thing reads as a defence against complaints that he mismanaged the war effort by not acting more offensively.

There’s also a good dose of racism, which might not surprise when considering the figure.

Thaon di Revel was not just an admiral, he was also a senator and was a member of the cabinet under Mussolini. It doesn’t appear that he ever joined the Fascist party, but he definitely didn’t have any problems working with them.

His signature is on the Italian race laws of 1939 which reduced the Italian Jews to second rate citizens, and opened up the route to their later deportation to the Nazi concentration camps.

Once in Venice, the Austrian monument is being repurposed for Italian use. It has become a platform for Italian naval politics, without any reference to the origin or original purpose of the monument.

Localities

Photos of the column

Leave a Reply