Abito — Dress

The Lessico Veneto (Venetian Vocabulary) by Fabio Mutinelli was published in 1851. It is an invaluable tool for anybody who reads texts from the time of the Republic of Venice.

Fabio Mutinelli (1797-1876) was director of the I. R. Archivio Generale di Venezia (1847-1861), and a prolific writer on the history of Venice.

Dress

The style of the clothes of the Venetians was certainly not, as some believe, and endeavour to make believe, absolutely all their own; it was rather precisely that of the various nations, with which they gradually had political and commercial relations.

Dealing with the Lombards, therefore, the clothes of the Venetians were of canvas, adorned with broad stripes of various colours; the breeches were long, and the sandals open, alternately fastened by strings of leather, not exempting the Venetians, like the Lombards, to gird the sword, even in the serenity of peace.

Subsequently, trading with the Greeks of the empire, they used the serious and majestic robes of the East; blue having been the favourite colour of the ancient inhabitants of the Venetians (so that among the Romans blue and veneto were synonymous, and veneto was the name in Rome of that faction of the circus which dressed in this colour),1 so the aforementioned garments were generally of the blue colour. ¶

The men’s dress was a cassock, of wrought cloth, or quilted, and fastened at the hips by a belt. Over this dress, he wore a cloak fastened with a gold stud; on his head a cap, above which, on the forehead, two ribbons joined to form a cross. The dress of the females was of silk, long to the ground, low-cut, closed all over as to seem almost inconsequential, trimmed and adorned with embroidery. From the shoulders of these women descended, with two short strips of sable, a large mantle lined with gold with a little train, and they too wore on their heads a small cap, with a golden frieze, from which, loose and ringed, the hair vaguely escaped.

But when the customs of France, Germany and Spain came into vogue throughout Italy, at the turn of the fourteenth century, also the Venetians embraced them; therefore men, especially the young, the apprentices and the bandits, wore very long and narrow tied breeches of cloth (then called stockings), half of one colour and half of another, embroidered with silk, gold, silver, and sometimes with pearls (see Gavardina, Stafete, Zippon); therefore the females wore long and ample robes, of gold brocade, velvet, or silk cloths of scarlet, black, green, white, violet, and dark brown colour. ¶

These robes were adorned with gussets, precious fur, bells, and silver buttons; they were fastened with a belt also of silver; they had broad trains and sleeves and long to the ground, which ended at the tip in the manner of the Catalan shield, which was wide above, and narrow and pointed below. ¶

The men were shaved up to half an ear, with neck-long hair or a large and round hat on their heads: the females adorned their heads with certain nets of gold or silk, interwoven with pearls, called bugoli, then immeasurably adorned with expensive jewels, precious bracelets, and many rings of spinel. And in order not to soil their feet with dust or mud, since the streets of the city, where at the times men went riding, were not yet paved, the females used very high wide sandals without heels,2 a shoe, which was certainly uncomfortable and heavy, but was abandoned by them when they were in their houses, perhaps to take up another lighter one.

More then, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the females started to use the sumptuous and fantastic clothes of the other side of the mountain,3 and they competed in the new fashions and the hitherto unused gracefulness, announcing, more than the men, the arrival of limitless luxury. (See Provveditori alle Pompe).

Although the oriental dress had gone out of use, in any case the magistrates, the most sensible citizens, and the priests preserved its breadth and length. (See Cafetan, Dogalina, Zamberlucco).

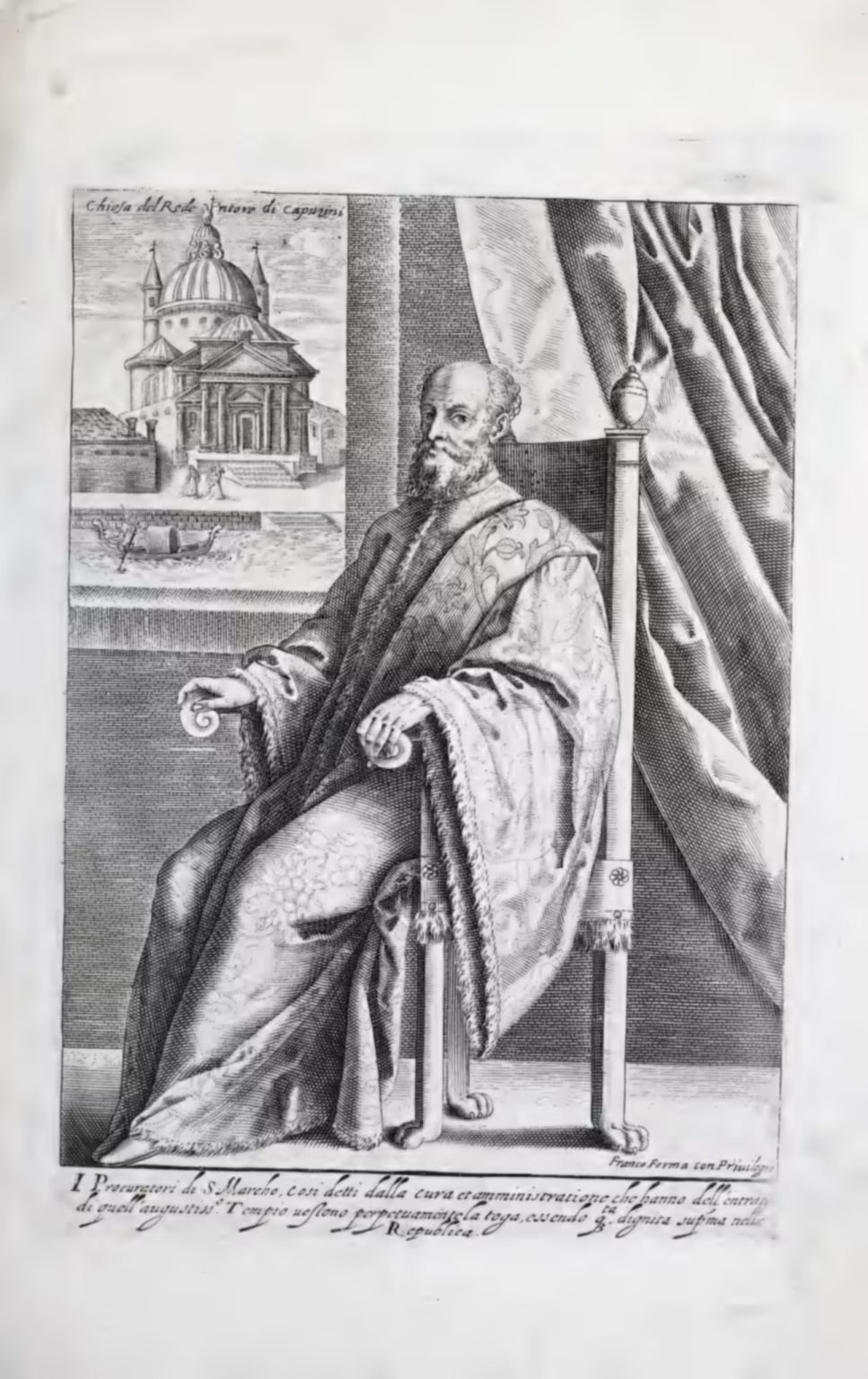

The magistrates therefore used the toga, or vesta, with wide sleeves and hoods, with linings in the winter of fur of vair,4 and in the summer of backs of vair, marten and ermine. At this latter time, they kept their robe open, and, when it wintered, fastened at the waist with a belt, adorned with silver buckles; the belt of the Knights of the Golden Stole,5 as a distinction of their rank, had golden buckles. ¶

From the left shoulder descended a piece, or strip, of cloth over the garment of the same colour as it, resulting half in the front, and half behind the person; this strip of cloth was called stole, and was also used for the custom of covering the head, to shield it from the rain, the wind and the cold. ¶

The Heads of the Council of Ten6 and the Avogadori del Comune7 wore the stole of red, even differing the colour of the robe according to the variety of offices, wherefore, for example, that of the Senators8 was purple, violet that of the Savi Grandi9 and the Councillors,10 red that of the Heads of the Council of Ten, of the Avogadori and of the Great Chancellor.11 ¶

When the hood fell into disuse, it was replaced by a woollen cap, dyed in black, topped with silk, round and somewhat wide, called a squat cap; When the fashion of wigs came in 1668, instead we shall see in its place, the cap no longer served to cover the head, but was carried in the hand almost as a complement and as a finish to the public dress.

The subordinate ministers, lawyers, and physicians also used the same dress; but their garment was always of woollen cloth or black rash,12 fastened with iron rings at the collar, from which the shirt came out well arranged.

The secular clergy dressed likewise. The simple priests used the black robe, the parish priests blue or violet, the clerics dark grey or ash, not ceasing to flaunt a sumptuous overgarment of fur and silk, and to gird themselves with a gold or silver band. This clothing, however, lasted until the sixteenth century; for the habits of those of Rome were then introduced among the ecclesiastics of Venice, the priests were advised to assume the vestments used by the Roman clergy, which were almost the same as those which the priests now use.

In consequence of all this, after the thirteenth century, there were found in Venice three Guilds, or Guilds of tailors under the names of Sartori da veste,13 Sartori da ziponi, i.e. jackets, Sartori da calze; the first of whom worked exclusively the robes, the second the jackets, the third the very long and narrow breeches.

The dress of the soldiers too went hand in hand with that of the others in Europe. Therefore, in the days more distant from us the same forms of helms and crests, the same shields, the same camouflages and the same greaves; in the seventeenth and seventeenth centuries the same shirt of mail with the iron corselet on it, and the same breeches as in the Spanish court, and enlarged to excess; in the eighteenth century the same ridiculous dress, known to anyone, of the other European soldiers, only by Napoleon Bonaparte at the beginning of the present century reduced to more martial, more convenient and more elegant forms. ¶

But the armament of the navy soldiers, for whom during boarding an overabundance of arms could be damaging, was lighter and slimmer; they wore therefore a helmet of iron or leather, and a short cuirass, they carried a shield, and had a sword, three spears, and a dagger.

When the eighteenth century arrived, patricians and citizens used that inconclusive overgarment called velada,14 which, according to the conditions and possessions, was of samite,15 velvet, satin, woollen rash or cloth with embroidery and expensive buttons, of simple cloth; they used shirts, breeches up to the knee, stockings of silk, linen, or wool (see Calze a barulè), shoes with buckles, and the tricuspid hat superimposed on shoulder long hair, or a wig, diligently arranged and scattered all with fragrant powder of Cyprus.16 ¶

Since it was never possible to go out without a cloak,17 so there were several kinds. For the winter there was the scarlet woollen cloak, and it was used for gala, there was one of white cloth, another of blue cloth; for the spring there was the white silk cloak with a lining; for the summer another of silk, although white, without a lining: the shopkeepers and artisans wore it of camlet.18

Except that, besides the introduction of the wig, it is known that the clothing of the magistrates always remained the same until the disappearance of the republic, as we saw it, remaining likewise, until that same period, uncorrupted and specifically of the Venetian females two forms of very popular clothes, which, both from our own and from foreigners, having always been recognized as such, we cannot comprehend, nor understand why now, to true national shame, they have gone into disuse.

The squandering of money made by these females to adorn themselves, had often called the attention of a government, which was justly instituted on simple and austere principles. ¶

Thus in the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries several laws were made, for which a limit was prescribed to the value of the fabric of the clothes, and to that of the accessories, so that at the end of the last of the aforementioned centuries, as Francesco Sansovino wrote, “The thing had been reduced to a very manageable and honest end, the women dressing then in black overgarments, every way in the Greek style.” ¶

From here, the Vesta e Cendà, a completely national dress, which ladies and women of civil condition used to wear in the morning as if they were domestic attire, must certainly have originated. This dress consisted of a skirt of black cendal19 (sometimes of other noble material of different colours) and a strip of the same cendal pinned over the head so as to cover and uncover the face as it may, and with much malice, and then terminated, somewhat twisted, in the loins, leaving the two ends fluttering on the back. ¶

The woman herself was then called Cendaleto when she was covered by it; and the Cendaleto, as Giustina Renier Michiel said, had the magical power to embellish the ugly, and to make the attractions of the beautiful stand out more.

A white cloak, or rather a robe of linen fabric, all around adorned with finer cloth, or muslin, neatly and studiously arranged, was used by craftswomen and common women, who, with the same arts of the Cendaleto, by wrapping the head, covered part of the body. This dress was called Fazzuol, faziol, and nizioleto, and nizioleto, after the manner of the one who used the Cendaleto, was also called the female, who wore the said robe, being called nizioleti also those who courted those lower-class females.

In this way, when the Venetian men, having become inept, went, as we have seen, grotesquely dressed in velada, wigs, and tricorn hats, their women, on the other hand, offered in the simplicity of their clothes all the graces and the most exquisite elegance.

Finally, the females of the lowest class, particularly those who lived in the most remote districts of the city, used another clothing called Tonda, Meza Tonda and Bocassin, which was a skirt or a comfortable apron, mostly of linen cloth, tied at the back to the waist, and rolled up on the head, which remained covered by it. Offering this robe to the front a spheroidal figure, so it was given the name of Tonda and Meza Tonda; and if it was also called Bocassin, perhaps it could have happened because it was formed in ancient times of that cotton cloth, which, in a barbaric voice, was called Boccassinus.

We will note that the Tonde have not yet disappeared from Venice.

All these different forms of clothing are already depicted, some in the most ancient mosaics of St. Mark’s Basilica, some in the many canvases of our painters, beginning with that unknown man, who in 1310 painted the holy bishop Donato in the cathedral of Murano, to end with Pietro Longhi, who died around 1780, painter, who valiantly and faithfully treated, with a new and no longer seen style, any domestic subject, that is, conversations, loves, jealousies and even women in the act of giving birth. ¶

Therefore, in conclusion, we will say that any form of dress must be considered apocryphal, which is not taken from any of those monuments, undeniable for Venetian custom, as for ancient Roman costume are undeniable those that are being unearthed from the ruins of Pompeia and Herculaneum.

Translator’s notes

The pilcrows ¶ mark paragraph breaks, which I have added for readability. They are not in the original, which, however, has some very long paragraphs.

- Chariot racing in Ancient Rome was one of the most popular spectator sports, and the four participants had the colours red, blue, green and white. The sport continued in Constantinople, where the teams were reduced to two, blue and green. ↩︎

- Calcagnette (also pianelle or zoccoli) were tall platform sandals or clogs, worn by Venetian women to look taller, and not to soil their feet in the streets. See, for example, Prostitute al Bordello. ↩︎

- An euphemism for France and Germany. ↩︎

- Vair (Venetian and Italiano: vaio) is the fur of the Baltic or Siberian squirrels, especially the white belly of the winter coat. It was one of the most expensive types of fur, and often a part of the formal dress of the doge. ↩︎

- The Cavalieri di San Marco wore a golden stole. ↩︎

- The Cai del Consiglio di Dieci (Heads of the Council of Ten) were senior and powerful state officials charged with state security. ↩︎

- The Avogadori de Comùn served as public prosecutors, as guarantors of the legality of the political and administrative procedures of the Republic of Venice. ↩︎

- The Pregadi was the Senate of the Republic of Venice, and one of the most important institutions of the republic. ↩︎

- The Savi Grandi or Savi del Consiglio were a group of sages closely associated with the Doge and the Signoria. . ↩︎

- The councillors of the doge, often just called the consiglieri or the Signoria, one of the very highest offices of the republic. ↩︎

- The Cancelliere Grando was (roughly) the head of the civil service, an original citizen, not a nobleman. ↩︎

- Rascia (also rasa, English: rash) was a sturdy woollen fabric. ↩︎

- For an illustration, see Sartore Ducale. ↩︎

- For an illustration, see the nobleman on the right in Nobili al Cafè — Noblemen at the Café. ↩︎

- Sciamito (English: samite) was a fine quality silk cloth, commonly adorned with gold and silver threads. ↩︎

- Polvere di Cipri (lit: Cyprus powder) was the Venetian term for face powder. ↩︎

- The Tabarro (also: tabaro) was a loose cloak or cape, often made from lush materials for use in winter, fastened at the front. ↩︎

- Cammeloto (English: camlet) was an expensive, mixed fabric, most often of wool and silk, often in the colour of camel hair. ↩︎

- Cendalo (also zendalo; English: cendal) was a light fine cloth of raw silk or cotton, typically decorated with stripes. ↩︎

Original text

ABITI

La foggia delle vesti dei Veneziani non fu certamente, siccome talun crede, e s’ingegna di far credere, assolutamente tutta lor propria; fu piuttosto precisamente quella delle varie nazioni, con cui essi a mano a mano ebbero relazioni politiche e commerciali.

Trattando quindi co’ Langobardi, le vesti dei Veneziani furon di tela, ornate di larghe striscie di svariati colori; i calzoni erano lunghi, e i sandali aperti, alternatamente allacciati da stringhe di pelle, non lasciando essi Veneziani, come i Langobardi, di cignere, eziandio nella serenità della pace, la spada.

Successivamente praticando co’ Greci dell’imperio usarono le vesti gravi e maestose dell’Oriente; essendo poi stato l’azzurro il colore favorito degli antichi abitatori delle Venezie (di guisa che presso i Romani azzurro e veneto erano sinonimi, e veneta chiamavasi a Roma quella fazione del Circo, la quale vestiva di questo colore) cosi le vesti anzidette erano generalmente di colore azzurro. ¶

L’abito degli uomini era talare, di panno operato, o lavorato a trapunto, e fermo a’ fianchi da una cintura. Di sopra quest’abito portavasi un manto affibbiato con borchia d’oro; in capo una berretta, sopra la quale, dalla parte della fronte, andavano a congiungersi due fettucce in guisa da formare una croce. Era la vesta delle femmine serica, lunga sino a terra, scollata, chiusa tutta da sembrare quasi inconsutile, assettata e adorna di ricami. Dagli omeri di quelle donne scendeva, con due corte strisce di zibellino, un ampio manto listato d’oro con alquanto di strascico, e pur esse portavano in capo una piccola berretta, con aureo fregio, dalla quale, sciolta e innanellata, vagamente fuggiva la chioma.

Ma venute in voga per tutta Italia, sorto appena il secolo decimoquarto, le usanze di Francia, di Allemagna e di Spagna, anche i Veneziani le abbracciarono; laonde gli uomini, specialmente i giovani, i garzonastri ed i bravi, vestivan cotte ovvero gonnelle, succinte e tirate, ad esse portando legate lunghissime e strette brache di panno (allora appellate calze), mezze di un colore e mezze di un altro, ricamate di seta, di oro, di argento, e qualche volta di perle (V. Gavardina, Stafete, Zippon); laonde le femmine vestivano vesti lunghe ed ampie, di broccato d’oro, di velluto, o di panni di seta di colore scarlatto, nero, verde, bianco, pavonazzo e morello. ¶

Andavano quelle vesti adornate di gheroni, di pelli peregrine, di campanelle e di bottoni di argento; erano allacciale con una cintura parimente di argento; aveano strascichi e maniche larghissime e lunghe sino a terra, le quali terminavano in punta a guisa dello scudo Catalano, ch’era largo di sopra, e stretto ed acuto di sotto. ¶

Rasi gli uomini sino a mezzo orecchio poneansi sopra il capo una zazzera o capelliera grande e rotonda: le femmine si adornavano il capo con certe reticelle di oro o di seta, intramesse di perle, appellate bugoli, smisuratamente poi fregiandosi di monili ricchissimi, di preziose armille, e di molte anella di balasci. E per non insudiciarsi i piè di polvere o di mota, avvegnachè le vie della città, per le quali allora si cavalcava, non erano ancora selciate, usavano le femmine degli altissimi zoccoli larghi e senza calcagnino, calzamento, che per essere certamente scomodo e pesante, era però da esse abbandonato quando si trovavano nelle lor case, forse per riprenderne altro più leggiero.

Maggiormente poi nei secoli decimosesto e decimosettimo impresero le femmine ad usare le sfarzose e fantastiche vesti di oltramonte, e si diedero a gara alle nuove foggie e alle leggiadrie non usate, annunziando, più che gli uomini, il progresso di un lusso senza limite. (V. Provveditori alle Pompe).

Ancorchè andato in disusanza l’abito all’orientale, ad ogni modo dai magistrati, dai cittadini più assennati e dai preti serbata ne venne l’ampiezza e la lunghezza. (V. Cafetan, Dogalina, Zamberlucco).

Usavano quindi i magistrati la toga, o vesta, con larghe maniche e col cappuccio, con fodere il verno di vai, e la state di dossi, di faine e di ermesini. In questo ultimo tempo tenevasi la vesta aperta, e, quando vernava, stretta alla vita con una cintura, ornata di borchie di argento; la cintura dei Cavalieri della stola d’oro, per distinzione del loro grado, auree aveva le borchie. ¶

Dall’omero sinistro scendeva un pezzo, o striscia, di panno sopra la vesta di ugual colore di essa, riuscendo mezza al davanti, e mezza al di dietro della persona; questa striscia di panno appellavasi stola, e serviva eziandio all’ uso d’imbacuccarsi, affin di schermire la testa dalla pioggia, dal vento e dal freddo. ¶

I Capi del Consiglio dei Dieci, e gli Avogadori del Comune portavano la stola di color rosso, differendo eziandio il colore della veste secondo la varietà degli officii, laonde, per esempio, era purpurea quella dei Senatori, violacea l’altra dei Savii grandi e Consiglieri, rossa quella dei Capi del Consiglio dei Dieci, degli Avogadori e del Cancellier grande. ¶

Andato in disuso il cappuccio, si sostitui ad esso una berretta di lana, tinta in nero, soppannata di seta, rotonda e alquanto larga, chiamata berretta a tozzo; venuta nel 1668 la moda delle parrucche, siccome a suo luogo vedremo, non servì più la berretta a coprire il capo, ma ſu porlata in mano quasi a corredo e a finimento dell’abito pubblico.

I ministri subalterni, gli avvocati ed i medici usarono pure del medesimo abito; però la lor vesta fu sempre di panno o di rascia di color nero, allacciata con magliette di ferro al collare, d’onde usciva bene accomodata la camicia.

Il clero secolare vestiva del pari. I preti semplici usavano la veste nera, i parochi azzurra o pavonazza, i cherici bigia o cenerognola, non lasciando di ostentare uno sfarzoso soppanno di pelli e di seta, e di cignersi con una fascia d’oro, o di argento. Tale abbigliamento però ebbe durata sin al secolo decimosesto; imperocchè introdotte allora anche fra gli ecclesiastici di Venezia le abitudini di quelli di Roma, consigliati vennero i preti ad assumere eziandio le vesti usate dal clero Romano, le quali erano pressochè le stesse di cui i sacerdoti si valgono presentemente.

In conseguenza di tutto ciò, dopo il decimoterzo secolo, si trovarono a Venezia tre Arti, o Corporazioni di sarti sotto i nomi di Sartori da veste, Sartori da ziponi, cioè giubboni, Sartori da calze; i primi dei quali lavoravano esclusivamente le vesti, i secondi le giubbe, i terzi le lunghissime e strette brache.

Anche il costume dei soldati andò di pari passo con quello degli altri di Europa. Quindi nei giorni da noi più lontani le medesime forme di celate e di cimieri, gli stessi scudi, gli stessi camagli e gli stessi schinieri; nei secoli decimoseslo e decimosettimo la medesima camicia di maglia col soprappostovi corsaletto di ferro, e le medesime brache alla spagnuola corte, e gonfie a dismisura; nel secolo decimottavo il medesimo ridicoloso abbigliamento, a chiunque noto, degli altri militi Europei, solo da Napoleone Buonaparte nel principio del presente secolo a più marziali, a più convenienti e a più eleganti forme ridotto. ¶

Ma l’armadura dei soldati marittimi, cui nell’abbordaggio riuscir poteva dannosa una soprabbondanza di armi, era più leggiera e più snella; portavano dunque costoro un elmo di ferro o di cuoio, ed una corta lorica, imbracciavano uno scudo, ed aveano una spada, tre lancie ed un coltello.

Giunto il secolo decimottavo, patrizii e cittadini usarono quella inconcludente sopravvesta detta velada, la quale, conforme le condizioni e gli averi, era di sciamito, di velluto, di raso, di panno di lana con ricami e bottoni ricchissimi, di panno semplice; usarono la camiciuola, le brache sino al ginocchio, le calzelle di seta, di refe, di lana (V. Calze a barulè), le scarpe colle fibbie, ed il cappello tricuspide soprapposto a zazzera, o a parrucca, diligentemente accomodata e sparsa tutta di odorosa polvere di Cipri. ¶

Siccome poi non si poteva mai uscire senza ferraiolo, cosi ve n’erano di più specie. Pel verno eravi il ferraiolo di panno scarlatto, e si usava da gala, eravi quello di panno bianco, altro di panno turchino; per la primavera eravi il ferraiolo di seta bianca soppannato; per la state altro di seta, pur bianca, senza soppanno: i bottegai e gli artieri lo portavano di cammelloto.

Se non che, tolta l’introduzione della parrucca, si sappia che l’abbigliamento dei magistrati rimase sempre sino allo sparir della repubblica quale lo vedemmo, rimanendo del pari, sino a quella stessa epoca, incorrotte e tutte proprie delle femmine Veneziane altre due foggie di vesti vaghissime, le quali, e dai nostrani e dai forestieri, essendo state sempre per tali riconosciute, non possiamo comprendere, nè capacitarci perchè ora, con vera nazionale vergogna, siano andate affatto in disuso.

Lo scialacquo di danaro fatto da esse femmine per adornarsi, chiamato aveva più volte, l’attenzione di un governo, il quale giustamente era instituito sopra semplici ed austeri principii. ¶

Quindi nei secoli XIV, XV e XVI vennero fatte più leggi, per le quali si prescrisse un limite al valore dei panni delle vesti, ed a quello delle minuterie, di guisa che alla fine dell’ultimo degli accennati secoli, come scriveva Francesco Sansovino, «s’era ridotta la cosa a termine assai comportabile et onesto, vestendo allora le donne di sopra nero, in ogni lempo alla greca.» ¶

Da qui dee certamente aver tratto origine la Vesta e Cendà, abito del tutto nazionale, che le dame e le femmine di civile condizione portar soleano la mattina quasi abbigliamento alla domestica. Constava questo abito di una gonna di zendado nero (alcune volte di altra nobile materia di diverso colore) e di una striscia dello stesso zendado appuntata sopra il capo cosi da coprire e da scoprire a vicenda, e con assai malizia, il volto, per quindi terminare, alquanto attortigliata, ai lombi, lasciando i due capi svolazzare sul tergo. ¶

Chiamavasi poi Cendaleto la donna stessa quando n’era coperta; e il Cendaleto, come diceva Giustina Renier Michiel, aveva il magico potere di abbellire le brutte, e di far spiccare maggiormente le attrattive delle belle.

Un candido manto, o meglio un accappatoio di panno lino, tutto all’intorno adornato di tela più fina, o di mussola, acconciata con salda e studiosamente assettata, era usato dalle artigiane e dalle donne vulgari, il quale, colle stesse arti del Cendaleto, imbacuccando il capo, copriva parte del corpo. Fazzuol, faziol e nizioleto appellavasi questa veste, e nizioleto, a guisa di colei che usava il Cendaleto, chiamavasi anche la femmina, che portava il detto accappatoio, dicendosi nisioleti eziandio coloro, che faceano all’amore con quelle femmine di bassa mano.

Di sì fatta guisa quando i veneziani uomini, divenuti baggei, andavano, siccome abbiam veduto, grottescamente abbigliati in velada, in parrucca e col tricuspide cappello, le lor donne invece offrivano nella semplicità delle lor vesti tutte le grazie e la più squisita eleganza.

Finalmente, le femmine dell’infima classe, particolarmente quelle che abitavano nelle più rimote contrade della città, usavano un altro abbigliamento detto Tonda, Meza Tonda e Bocassin, il quale era una carpetta o un agiato grembiule, per lo più di tela lina, al di dietro legato alla cintola, e rimboccato sul capo, che ne rimaneva coperto. Offerendo questa veste al davanti una figura sferoidale, così le ſu dato il nome di Tonda e di Meza Tonda; e se fu appellata anche Bocassin, ciò forse potè accadere per essere stata formata in antico di quella tela di bambagia, la quale, con voce barbarica, dicevasi Boccassinus.

Avvertiremo, che le Tonde non sono ancora affatto scomparse da Venezia.

Tutte queste diverse maniere di vesti trovansi già espresse, quali nei più antichi musaici della basilica di san Marco, quali nelle molte tele dei nostri pittori, cominciando da quell’ignoto, che nel 1310 pinse nel duomo di Murano il santo vescovo Donato, per finire con Pietro Longhi, morto intorno al 1780, pittore, che valorosamente e fedelmente trattò, con nuovo e non più veduto stile, qualsivoglia domestico soggetto, cioè conversari, amori, gelosie e perfin donne in atto di partorire. ¶

Quindi, conchiudendo, diremo doversi considerare apocrifa qualunque foggia di veste, la quale non sia tratta da alcuno di que’ monumenti, irrefragabili per il Costume veneziano, quanto per il Costume antico romano irrefragabili sono quelli, che si van disotterrando dalle ruine di Pompeia e di Ercolano.

Related articles

Related works of art

Leave a Reply