The giuoco del pallone — the game of the big ball — also called palla da pugno (fist ball) or palla al bracciale (ball with arm guard) was the quintessential ball game.

Venetian Stories

This post is also available in audio format on the Venetian Stories Podcast.

The basic gameplay followed the definition of ball games by Antonio Scaino in his Treatise on the game of ball (1555): two teams without any direct physical contact, on a playing fields divided in two parts, one for each team, lopping a ball back and forth, until one team fails to return the ball.

If that sounds tennis-like, then yes, and no!

The game of Pallone is a distant ancestor of modern tennis, with some emphasis on ‘distant’.

There were many differences.

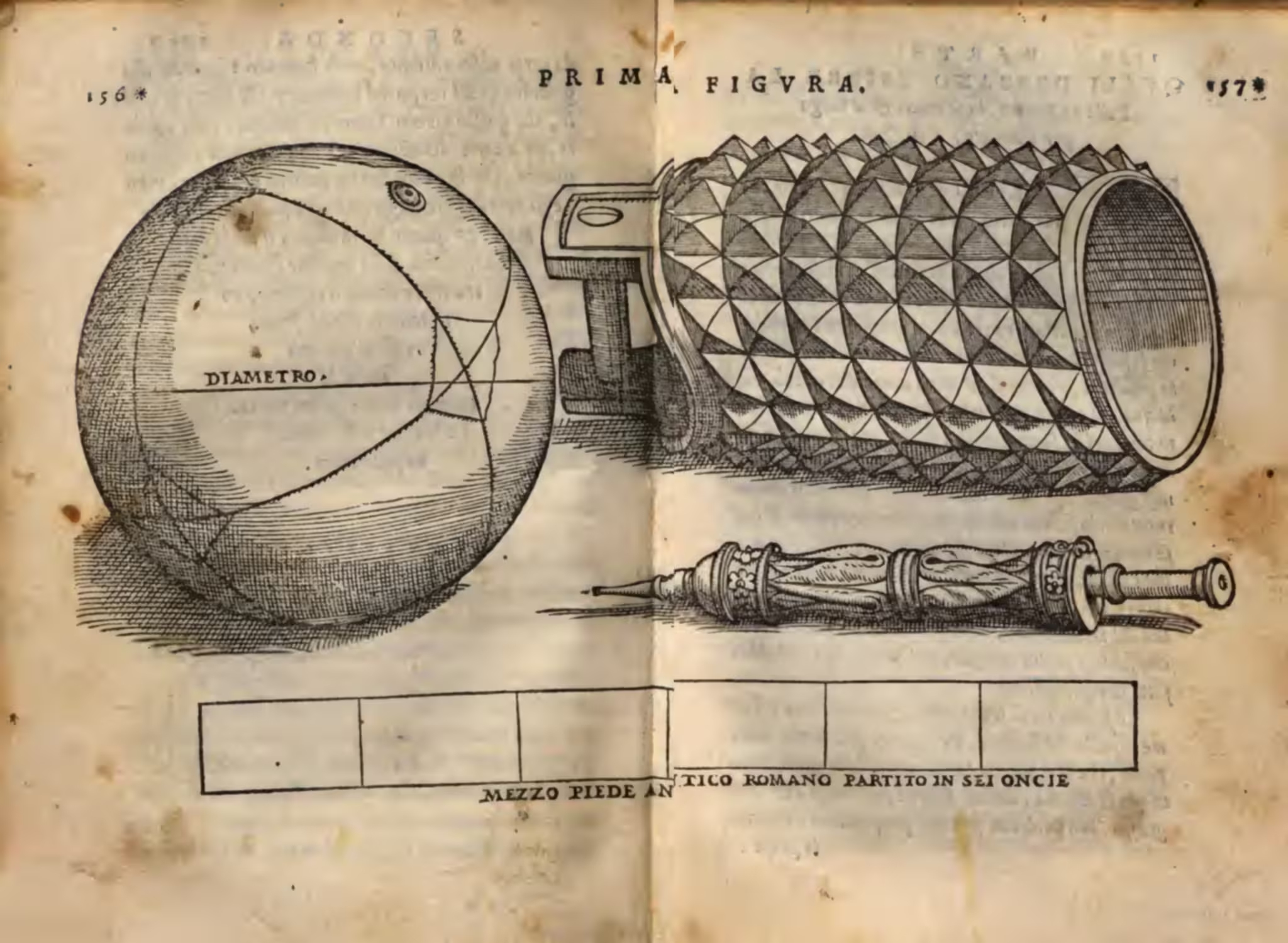

The players were three or four on a team, and instead of a racket they hit the ball with a wooden arm guard with spikes (called a bracciale or brazzal), which could weight 2kg. The ball was inflated, and larger than a modern football.

The system of points is not dissimilar, with each game worth 15 points.

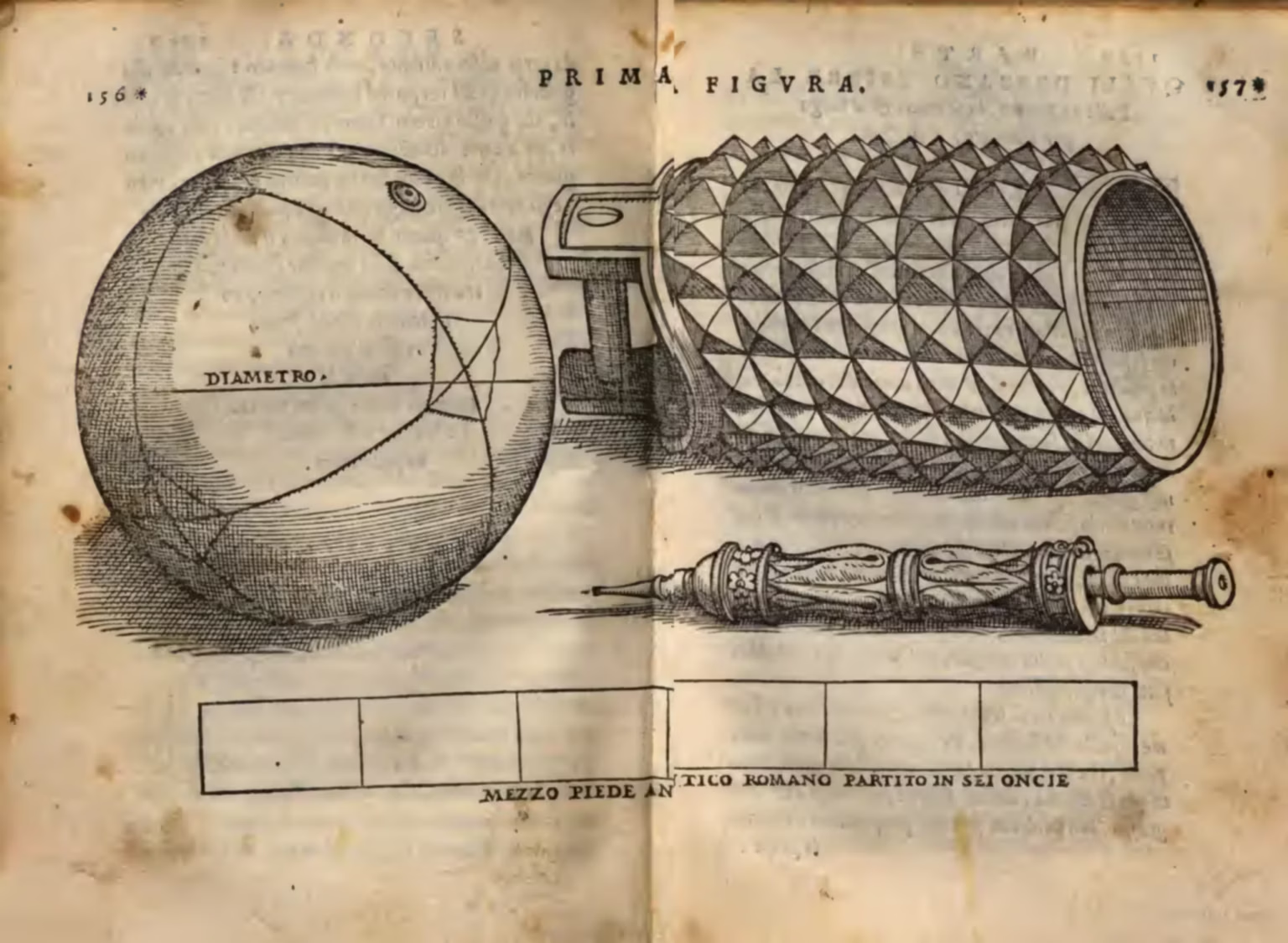

The brazzal or bracciale

The most striking part of the game is the solid wooden arm guard, the brazzal (in Venetian) or bracciale (Italian).

In origin, it was played hitting an inflated ball with the fist, but soon protective guards developed into a rather articulate arm guard.

The arm guard was made of wood, walnut or ash, most commonly. A round piece of wood, about twice the diameter of the player’s forearm, with the core drilled out, so the hand could pass through. The length of the arm guard should be from the wrist to a few fingers’ width short of the elbow.

Preparing for a game, the player wrapped his forearm with a piece of woollen or linen cloth, and then slid his forearm, left or right as his leisure, into the arm guard. If it was too loose, other pieces of cloth were used to make a comfortable fit.

The player held the arm guard in place by closing his fist around a stick, which was nailed across the lower end. Sometimes, a protrusion of the main arm guard served as a further protection for the hand, not unlike what one commonly sees on sword hilts.

The main, cylindrical, part of the brazzal was covered in spikes, so it had a hedgehog-like appearance. They were pyramid shaped, and either cut into the wood, or nailed on.

This rugged surface of the arm guard lessened the impact on the player’s arm, prevented the greasy ball (as we shall see) from slipping, but also allowed the player to spin the ball to make it harder for the opponents returning it correctly.

According to Scaino, seven bands of fifteen spikes each were the correct number.

Strings were often bound tightly around the arm guard, in-between the bands of spikes, to prevent it from breaking during a game, or to hold a cracked or broken brazzal together so it could be re-used.

A correctly fitted brazzal would allow the player to deliver a forceful blow, both forehand and backhand, without causing any pain or injury. Some players could even, theatrically, hit the ball behind their back.

The pallone or balon

The ball used for the giuoco del pallone was an inflated ball, about the size of a modern football or a bit bigger.

Scaino says the diameter should be around one Roman foot and an ounce, which, I believe, is a bit more than thirty centimetres.

For the curious, I base this on an Italian manual in metrologia — weights and measures — from the 1880s, which has conversions from all the commonly used ancient measures used in the pre-unification Italian states, to metric. A Roman foot was approximately 29.8cm, subdivided into 16 ounces.

The ball was made of three layers. An inner layer to contain the air, either the bladder of an animal, or very fine leather sewn together and greased copiously; a middle layer of suede to protect the air-chamber; and an outer layer of well-greased goat-skin leather.

Goat-skin leather — also often called marocchin — is thin, soft, flexible and very expensive.

Each layer of the ball consisted of eight identical pieces, which, when sewn together, looked triangular, with a small square reinforcement where four such pieces met.

Scaino emphasised the need for the ball to be greased generously, so the outside shell of goat-skin leather would retain its flexibility and expand evenly, so the ball remained perfectly round when inflated.

The greasiness of the balls might be one of the reasons for the spikes on the arm guard. Had the brazzal been smooth, the player would have very little control over where the ball actually went.

It was not unusual for balls to explode or deflated during the games. In such cases, the point wasn’t lost, and the game replayed afresh.

The balls had to be inflated quite hard, so each ball was used for one game, and then handed over to an infiador — an ‘inflater’ — who would inflate the ball again, using a schizzeto — a pump which looked a bit like a manual bicycle pump.

Players

Each of the two teams were three or four players, of which one was the battitore (hitter), to his left the spalla (shoulder) or sentina (a term also used in Venetian rowing, meaning the second-most important of the crew), and the last was the terzina (third), of which there could be two, both to the right of the hitter.

Gameplay

To start a round of the game — called a caccia, or, in Venetian, a cazza — an assistant, called the mandarin, threw the ball into the air in front of the hitter, who, standing still or running down a ramp, hit the ball with his arm guard.

The ‘hitter’ had to send the ball in the air into the opposite half of the court. The ball had to pass the centre line in the air, not stray outside the playing area, neither to the sides not in the back.

The players of the opposing team could hit the ball only once, either before it hit the ground, or after a first rebound, to return it to the other team. If they failed to hit it, or if it rebounded twice, or started rolling on the ground, or if they sent it off the playing area, they lost the round.

No parts of the players could touch the ball, if not hitting it with their arm guard. The arm guard was not allowed to touch the ground when striking the ball.

If the playing field had a wall on one side, the players could be allowed to bounce the ball off the wall, without losing the caccia.

This playing back and forth repeated, until one team failed to return the ball without fault, so a round could go on for quite some time, if two equally skilled teams faced each other.

Another assistant counted the points as the rounds progressed. Each caccia was worth fifteen points, so the progression was 15 – 30 – 45 – game.

The game was won when one team reached 60 points, provided they were two cacce in advantage. If both teams arrived at 45, the score was reset to 30 – 30, and play would continue until one team won two successive cacce. When that happened, no matter how many rounds they played, the score would still be 30 – 60.

Over time, the assistant who counted the points, began to shorten the announcements, so the sequence 15 – 30 – 45 – game, became 15 – 30 – 40 – game.

A game would therefore consist at least four cacce, but could in principle go in indeterminately.

Victories were divided in three categories.

A simple victory was a normal, straightforward win, worth one point.

A double victory happened when the opposing team won no cacce at all, that is, when one team won all the first four consecutive cacce. Such a victory was valued double.

The third category was called triple or rabioso — literally ‘raging’ or ‘furious’. A victory was rabioso when one team had been down zero to 45, and yet went on to win in straight sets. This could only happen if one team won the first three consecutive cacce, and then the other team the next five consecutive cacce. A ‘furious’ victory was valued triple.

Matches could consist of many games, but at the time of Scaino, there don’t seem to have been any formal rules. Maybe the players just agreed beforehand, how many games to play, like “best of seven”; or they agreed on a number of point needed for a match victory, since some games could be double or triple; or they simply played for a predetermined time, and the team with the most points won.

Later on, when the game of pallone became a more organised sport, with special areas for the games, rules for longer matches appeared.

Then, one team started each caccia for two consecutive games, which were called a trampolino. The name is derived from the ramp, or trampoline, the hitter sometimes descended for the initial blow.

A complete match consisted of a number of trampolini, usually five.

Consequently, instead of game-set-match as in modern tennis, they had caccia-game-trampolino-match.

Gambling

The value of a game was important, not just for the game itself, but for all the betting and gambling which inevitably happened around the matches.

Gambling was inevitable around the games for several reasons.

Firstly, the Venetians were compulsive gamblers.

The word ‘casino’ originates in Venice, in the meaning of a venue of gambling, and the Republic of Venice even ran an official casino, to which only Venetian and foreign nobles had access. This place was a palace not distant from San Marco, near the San Moisé church, called the Ridotto, in the sense of a meeting place.

In the 1700s, the Ridotto was a fixture on the Venetian high-end entertainment scene.

Another reason why betting and gambling around the matches were inevitable, was that they happened in public squares.

The game of pallone in Venice

The space required for the game was such, that no in-door venue of the time was sufficient.

In Venice, the game of pallone was therefore played in public, under an open sky.

The most popular playing fields in Venice were the Campo di San Giacomo dall’Orio in the Sestiere Santa Croce, and the Campo dei Gesuiti in Cannaregio.

Giuseppe Tassini, in his inevitable Curiosità Veneziane for the entry Giacomo dell’Orio, quotes a document from the archives of the late Venetian historian Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna:

The noble game of pallone started with our patricians in Campo di S. Giacomo dall’Orio in the previous century (1600s), not, however, with the frequency of today, but because of the quantity of grass in the said place, it was transported to the Campo dei Gesuiti for several years. With the increase of the numbers and valour of the players, it was decided to pave over the above mentioned Campo di S. Giacomo in the year 1711, with the year carved in marble at the mark of the hitter.

According to this document, one of the main squares of Venice was paved over to make it better suited for the game of pallone.

Fun and games are no trifling matter.

In the entry for Gesuiti, Giuseppe Tassini wrote:

The game of pallone was prohibited in Campo dei Gesuiti by decree of the Council of Ten, April 21st, 1711.

So, in 1711, the game was banned at the Gesuiti but not wanting to stop playing, money was spent to revert in style to the previous venue.

They did take their fun and games rather seriously.

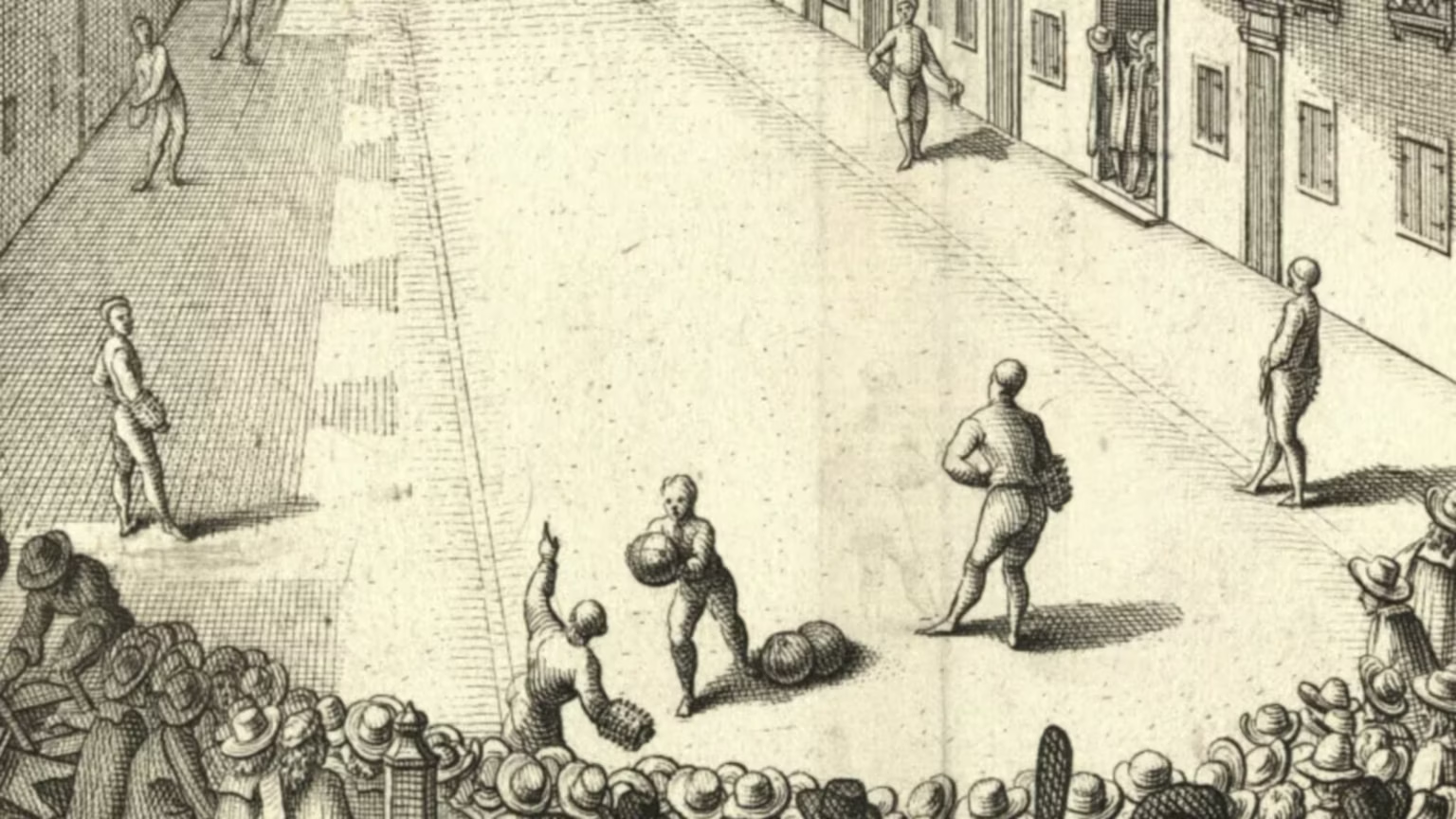

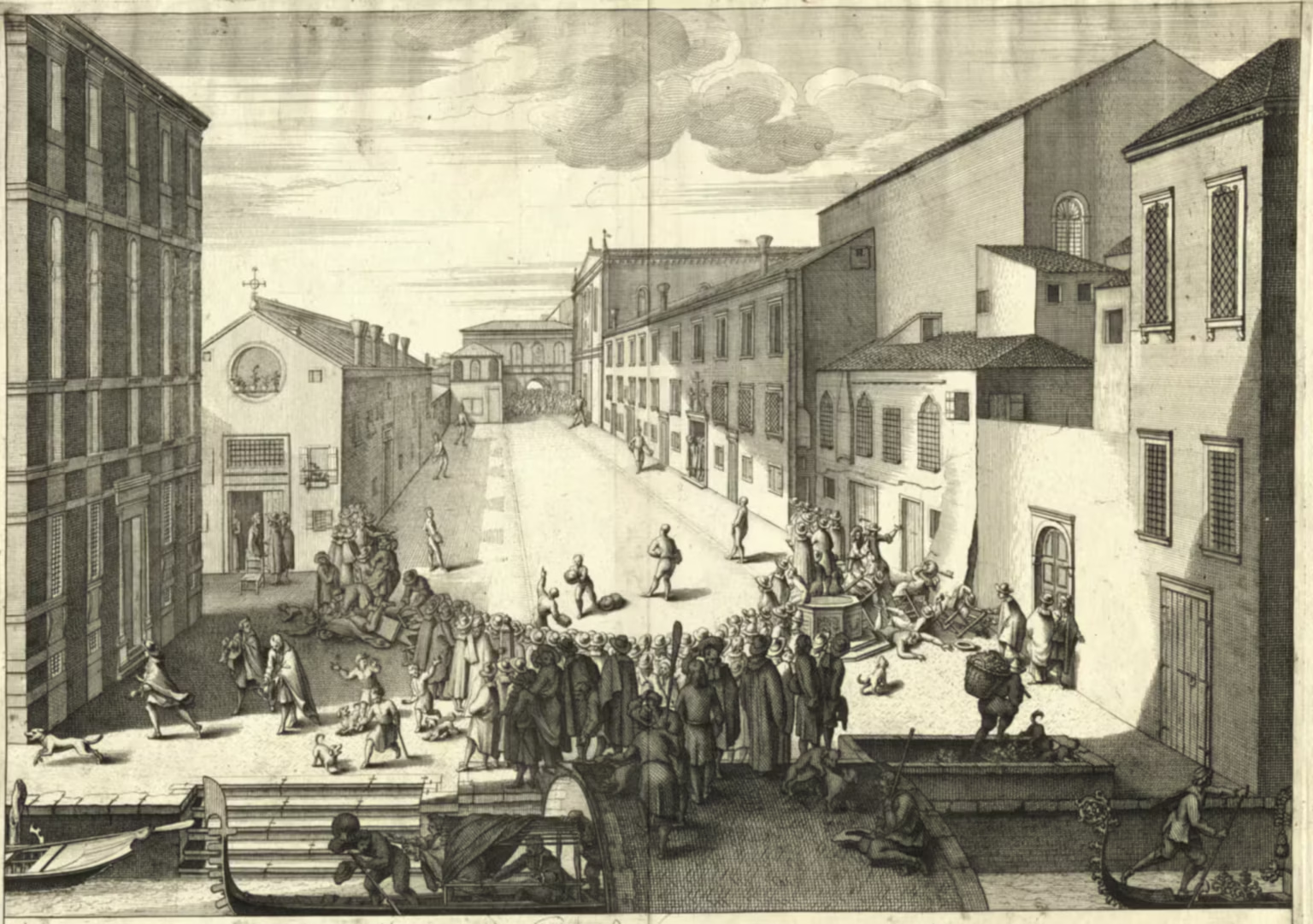

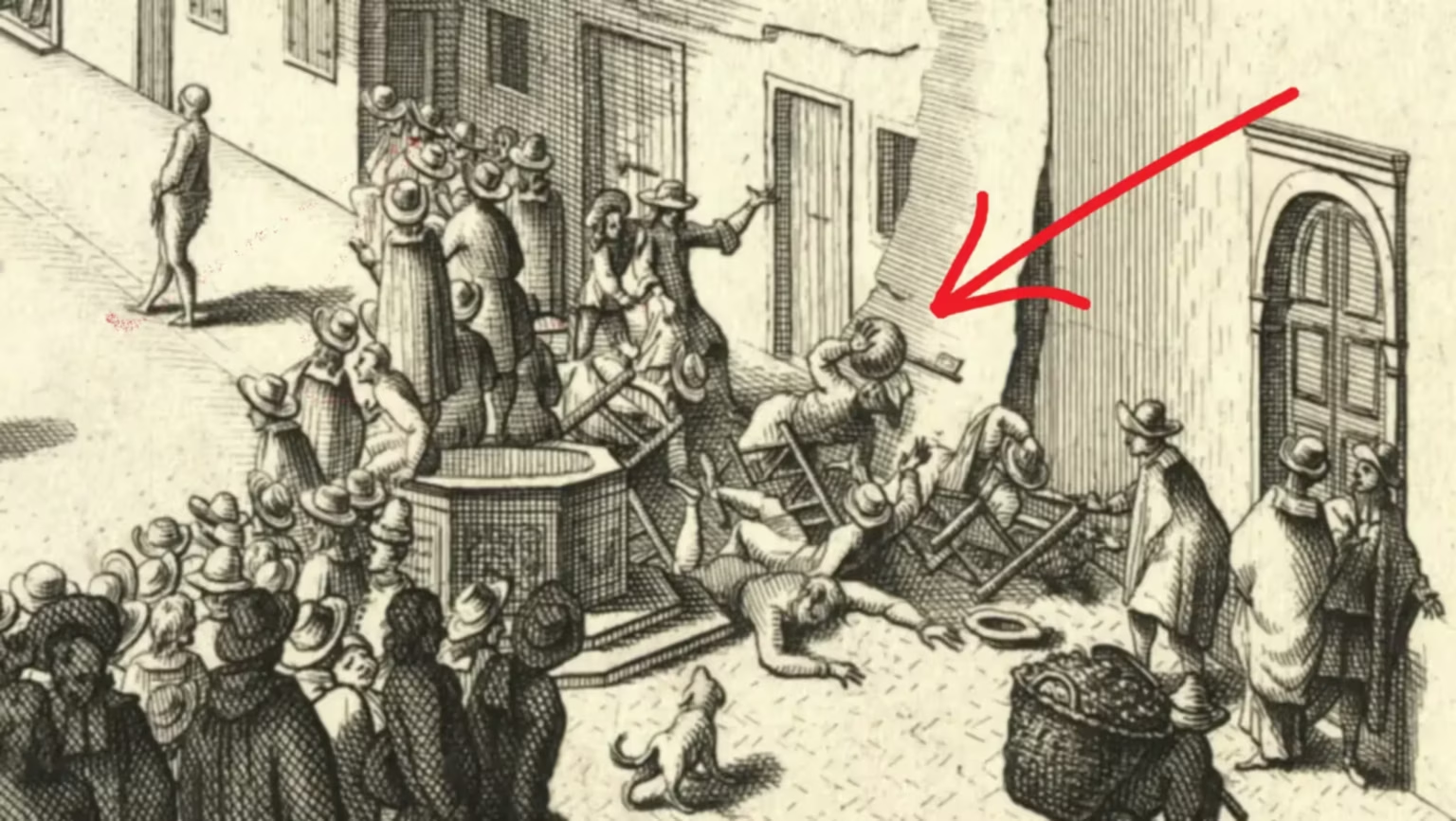

From the Campo dei Gesuiti, we have a marvellous engraving from one of the first decades of the 1700s, by an unknown artist, but published by Domenico Lovisa sometimes after 1715.

There are some quite interesting details in this print.

In the central part, we see the two teams of four lined up for a caccia. The team closest to us start the game, and the hitter is ready to hit the ball, which the mandarin is about to toss in the air in front of him. Two more balls lie ready at the feet of the mandarin. The players appear relaxed, but ready for the serve.

A half-circle of spectators stand between us and the players.

However, if we look carefully on the right side of the crowd, there’s a bit of disorder. Several persons are falling and chairs have been knocked over. An excited dog is barking at the people on the ground. Close to the wall, a man is knocked over by a large ball, hitting his head forcefully.

On the other side of the half-circle of spectators, there’s a similar scene. Chairs knocked over, and people lying on the ground. Three well-dressed men are leaving, two of them with their hats in their hands. One is looking back towards the game, while the other dusts the dirt of his hat. They’ve had enough.

A man with a crutch is running towards the canal in the foreground of the print. Following him, we find the ball which caused the chaos. It is striking the rower of a gondola passing by, the man is crouching down to deflect the blow, his hat knocked off, while his mistress is rushing out of the boat’s cabin to see if he’s hurt.

The game was banned at the Gesuiti in 1711, and this engraving was published just a few years later, sometimes between 1715 and 1720.

It is difficult not to see these marginal, almost humorous, episodes in the print as a critique of the game, and of the danger it presented to the spectators and to casual passers-by. A danger, which might have been the reason for the ban on the game in that square.

Ball games in daily language

The lasting popularity of the game of pallone is attested by the many entries for game related terms in the 1829 dictionary of the Venetian language by Giuseppe Boerio. Besides all the major terms for the game, its equipment and gameplay, he mentions several sayings and idioms, which were derived from the giuoco del pallone.

He has the entry ZOGAR AL BALÓN — playing at ball:

Ball-ing or playing at ball. The balon is a large ball for games, made of leather and full of air by means of a hole which inside is closed by a valve, which is hit by the arm with a guard of wood, covered in spikes.

This is, of course, the game we now all know and love.

However, he also has ZOGAR AL BALON DE UNO, — playing at ball with somebody or playing somebody at ball:

figuratively speaking playing somebody. pulling somebody here and there; one wanting one thing, and another another thing.

I think we call that gas-lighting today.

Regarding the brazzal, Boerio lists the expression VEGNIR SUL BRAZZAL — to fall on the arm guard:

figuratively speaking, cutting across; the rebound of a ball into the hand. The arrival of an opportunity.

and ASPETARÒ CH’EL ME VEGNA SUL BRAZZAL — I’ll wait for it to fall on the arm guard:

Waiting for the pig at the oak, or the rebound of the ball, said figuratively.

Now, few of us modern city dwellers ever wait for pigs under oaks, but the meaning is that of an easy win: I’ll wait until it comes around by itself. What goes around, comes around.

For the less experienced or learned in porcine matters, that is, related to swine, hogs, pigs and such: pigs like acorns which are the fruit of the oak, so if you wait under the oak, the pigs will come around, to stuff their snouts, when they get peckish.

Related articles

- Ball games in Venice

- The game of Calcio

- Nobile al Giuoco del Pallone — Grevembroch 1-89

- Nobile al Giuoco del Calcio — Grevembroch 1-87

- Nobile alla Rachetta — Grevembroch 1-94

- Il Gran Teatro di Venezia — plate 35 — Veduta del Campo de’ Giesuiti

Venetian Stories

Bibliography

- Boerio, Giuseppe. Dizionario del dialetto veneziano. Venezia : coi tipi di Andrea Santini e figlio, 1829. [more] 🔗

- Colasante, Gianfranco. Antichi giochi italiani in Enciclopedia dello Sport. Treccani, 2004. [more] 🔗

- Martini, Angelo. Manuale di metrologia, ossia, Misure, pesi e monete in uso attualmente e anticamente presso tutti i popoli. Torino, Ermanno Loescher, 1883. [more] 🔗

- Scaino, Antonio. Trattato del giuoco della palla di messer Antonio Scaino da Salò, diuiso in tre parti. Con due tauole, l'vna de' capitoli, l'altra delle cose piu notabili, che in esso si contengono. In Vinegia appresso Gabriel Giolito de' Ferrari, et fratelli, 1555. [more] 🔗

- Tassini, Giuseppe. Curiosità Veneziane ovvero Origini delle denominazioni stradali di Venezia. 1863. [more] 🔗

Leave a Reply