The Venetians of yore — like many other European people — played ball games for fun and sports.

Venetian Stories

This material is also covered by the Venetian Stories Podcast.

Some of these ball games were almost, but not quite, unlike some modern sports, even if not excessively. Others are by now long gone and forgotten.

Sports in the part were for the more affluent. In Venice, that meant the citizen and noble classes, that is, those who didn’t have physically hard work, and who had leisure time available for play.

The various ball games

At least three different ball games appear to have been popular in Venice, also over very long periods of time.

The first — and according to some sources also the most ancient — was called giuoco al calcio. The word calcio means a kick, and it is the word used in modern Italian for European football, but the game was probably more like rugby.

It also seems that there were at least two different games with this name, as different sources give conflicting descriptions.

In Venice, it was played during Lent, and often on the old shooting grounds at Sant’Alvise in Cannareggio.

- The game of Calcio.

- The game of Calcio, episode 15 of the Venetian Stories podcast.

Another game, usually just called giuoco al pallone — playing at ball — involved a wooden arm guard, which was used to hit a football sized ball back and forth across a field, between two teams.

This game was often played in the Campo dei Gesuiti in Cannaregio, and in the Campo di San Giacomo dell’Orio in Santa Croce.

This game remained popular in Northern Italy until the early 1900s, and was considered a national sport of the Kingdom of Italy in the late 1800s, under the name Pallone col bracciale.

- The game of Pallone, episode 16 of the Venetian Stories podcast.

- Playing at ball, issue of the Venetian Stories newsletter.

Finally, less physical versions of the above game developed, where a smaller ball was lopped back and forth over a rope, using a racket. Such games could be played by fewer players, in more limited spaces, therefore also indoors, and all year. This was the giuoco alla corda — a precursor of modern tennis.

Treatise on the game of ball

The essential source for renaissance ball games is a treatise by Antonio Scaino da Salò, who in 1555 published the Trattato del giuoco della palla di messer Antonio Scaino da Salò, diuiso in tre parti. Con due tauole, l’vna de’ capitoli, l’altra delle cose piu notabili, che in esso si contengono.

Translated, the title means: “Treatise on the game of ball by Mr. Antonio Scaino from Salò, divided in three parts, with two tables, one of the chapters, the other of the most notable things contained therein.”

It is sometimes referred to as the first book on tennis, but it is much more than that.

Antonio Scaino was born in Salò on the Lake Garda in 1524, to a noble and affluent family. Consequently, he went to study philosophy and theology at the University of Padua.

Following his studies, ordained priest, he found his way to the court of the Dukes of Ferrara, where he remained for much of the 1550s. Here, he became close to the younger brother of the duke, Alphonso d’Este, to whom the treatise on ball games is dedicated.

Alphonso d’Este — as was often the case with younger siblings of Italian dukes — became a cardinal, and went to Rome. Scaino followed him soon after, and had a quite brilliant career at the court of the Pope, where he wrote and published extensively on Aristotelian philosophy.

He died in 1612, shortly before his 88th birthday.

The Trattato del giuoco della palla, written in his younger years, was probably almost a joke for the erudite priest. Maybe he was called on to adjudicate issues, which arose during ball games his ducal friend played, as there are several such cases discussed in the treatise. Therefore, the writing of the book was likely a favour to his high placed friend and benefactor, but it is by far his most cited work ever.

What’s a ball game

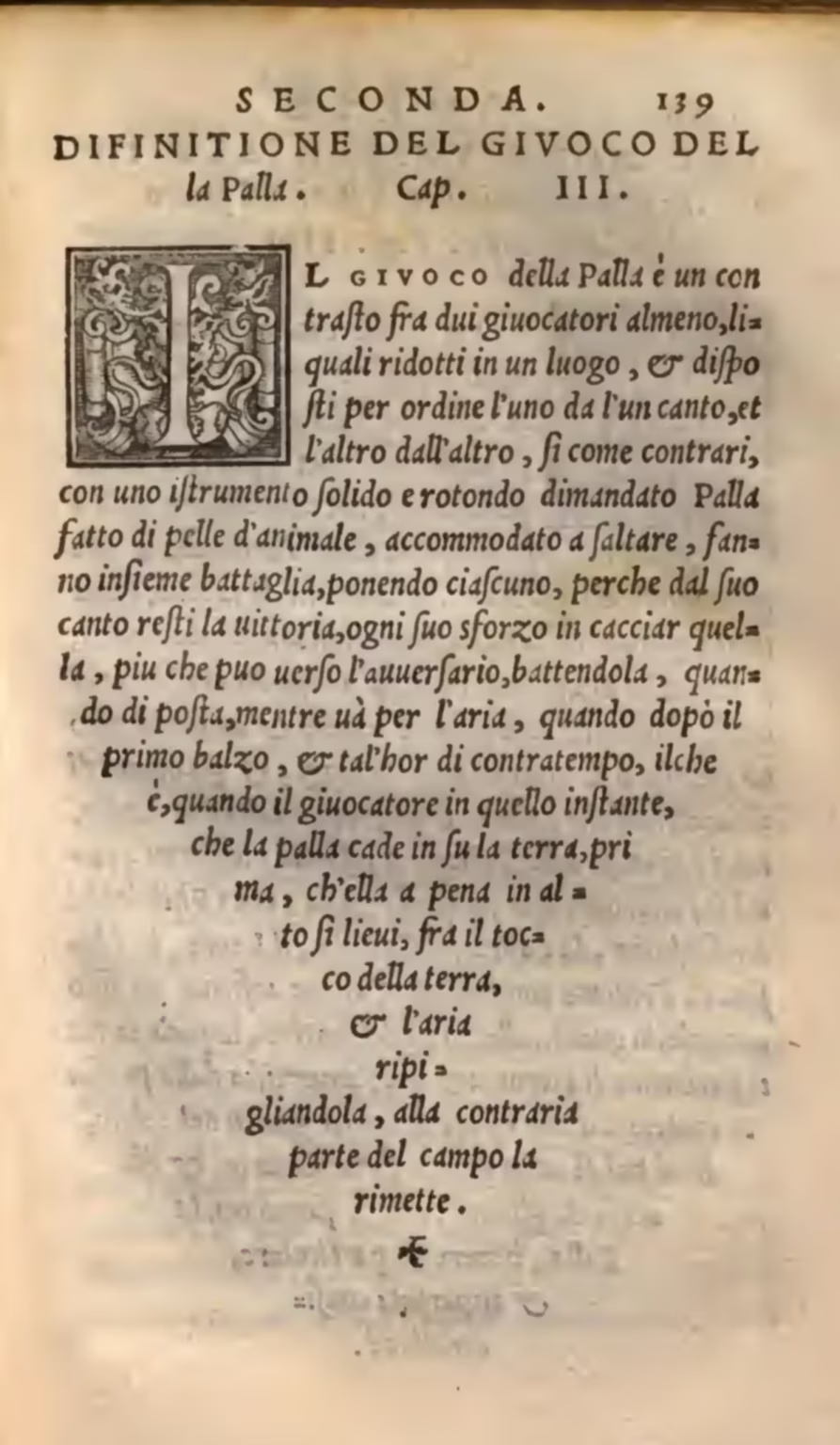

Scaino — being the good academic — offered a formal definition of what a ball game is:

The Game of Ball is a confrontation between at least two players, who assembled in a place, and disposed in order, one on the one side, and the other on the other, as opponents, with a solid and round instrument, called Ball, made of animal hide and made to bounce, engage in battle, employing each, so the victory may fall to their side, every possible effort in sending it [the ball] towards the adversary, hitting it, when it is in the air, after the firsts bounce, and at times accidentally, which is, when the player in that instant that the ball falls to the ground, just before it rebounds up high, between touching the ground and in the air, retakes it, and sends it to the other end of the field.

Scaino (1555), p. 139.

This definition doesn’t include the game of calcio, which Scaino readily admits, but he didn’t consider calcio a real ball game, no matter how vivacious and entertaining it was. It was not a noble sport, in his view.

Modern games like tennis and volleyball fit the definition.

There were two types of ball: a smaller stuffed ball, usually full of wool, and a larger, inflated ball.

The inflated ball — a ball of wind — was made of leather on the outside, and the bladder of an animal as the airbag, with a layer of suede in-between. A simple valve, made of a small flap of leather, kept the air in, and a mechanical pump, not unlike a bicycle pump, was used to inflate it.

Each ball was inflated before being used in a game, and exploding balls were not uncommon.

The field could be flat or with a rope across. In any case, it usually had a dividing line in the middle, which the players weren’t allowed to touch or pass. The fields could also be divided by a rope or net, which the ball had to pass over.

The players could hit the ball using their open hands, fists, armoured fists or forearms (like with the arm guards in the giuoco del pallone), or with an instrument, such as a bat or a racket.

All this allowed for a wide range of ball games.

Together with team sizes from one to four players on each side, this made for a wide variation of games, and Scaino mentioned at least six distinct games.

With an inflated ball on an open field:

- Giuoco del pallone (the game of the big bal) or palla da pugno (fist ball), with arm guards, and teams of three or four;

- Giuoco del Scanno, with wooden bats, and teams of three or four.

With a stuffed ball (palla soda) on an open field (alla distesa):

- Giuoco della palla soda fatto alla distesa, played with open hands or bats;

- Giuoco della racchetta alla distesa, played with rackets.

With a stuffed ball on a field divided by a net (alla corda):

- Giuoco della palla soda fatto alla corda, played with open hands or bats;

- Giuoco della racchetta alla corda, played with rackets.

Ball games were games

The ball games, which Scaino describes and explains in his treatise, were exactly that, games.

They were not organised like modern competitive sports, and few later writings on the matter exist, until much more recent times.

In the 1500s, and for centuries to come, ball games were fun physical and social activities for the affluent, that is, those who didn’t already engage in hard physical labour, and who had leisure time for play.

That, of course, doesn’t preclude endless discussions about whether that specific ball was a fault, or whether that victory the other Saturday was justified or not. Nevertheless, games can be serious matters for the participants and onlookers.

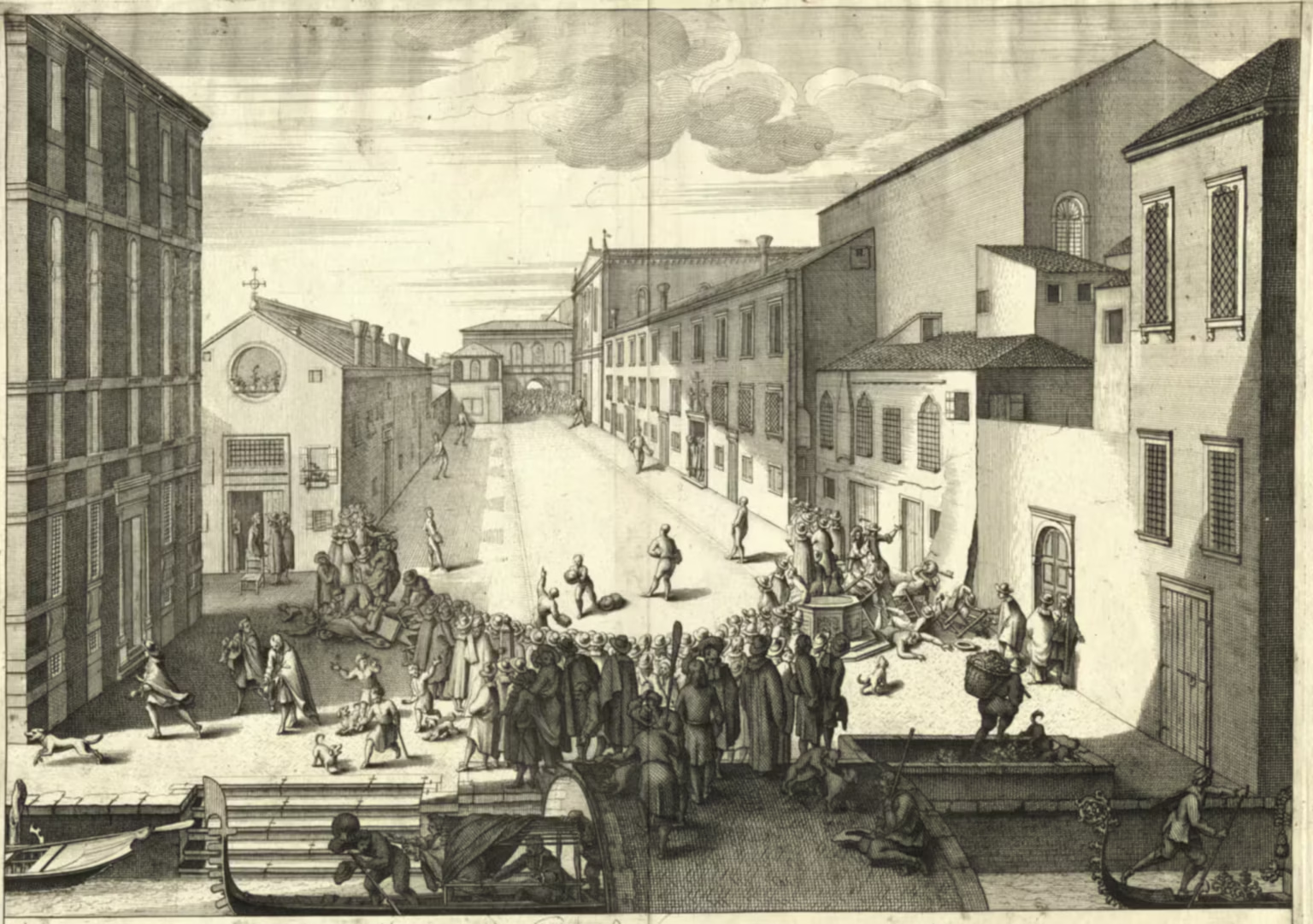

Most ball games didn’t have dedicated spaces for them. There was nothing like modern stadiums, or football pitches. They were mostly played in public squares, and some games became associated with certain campi in Venice, where the games were organised.

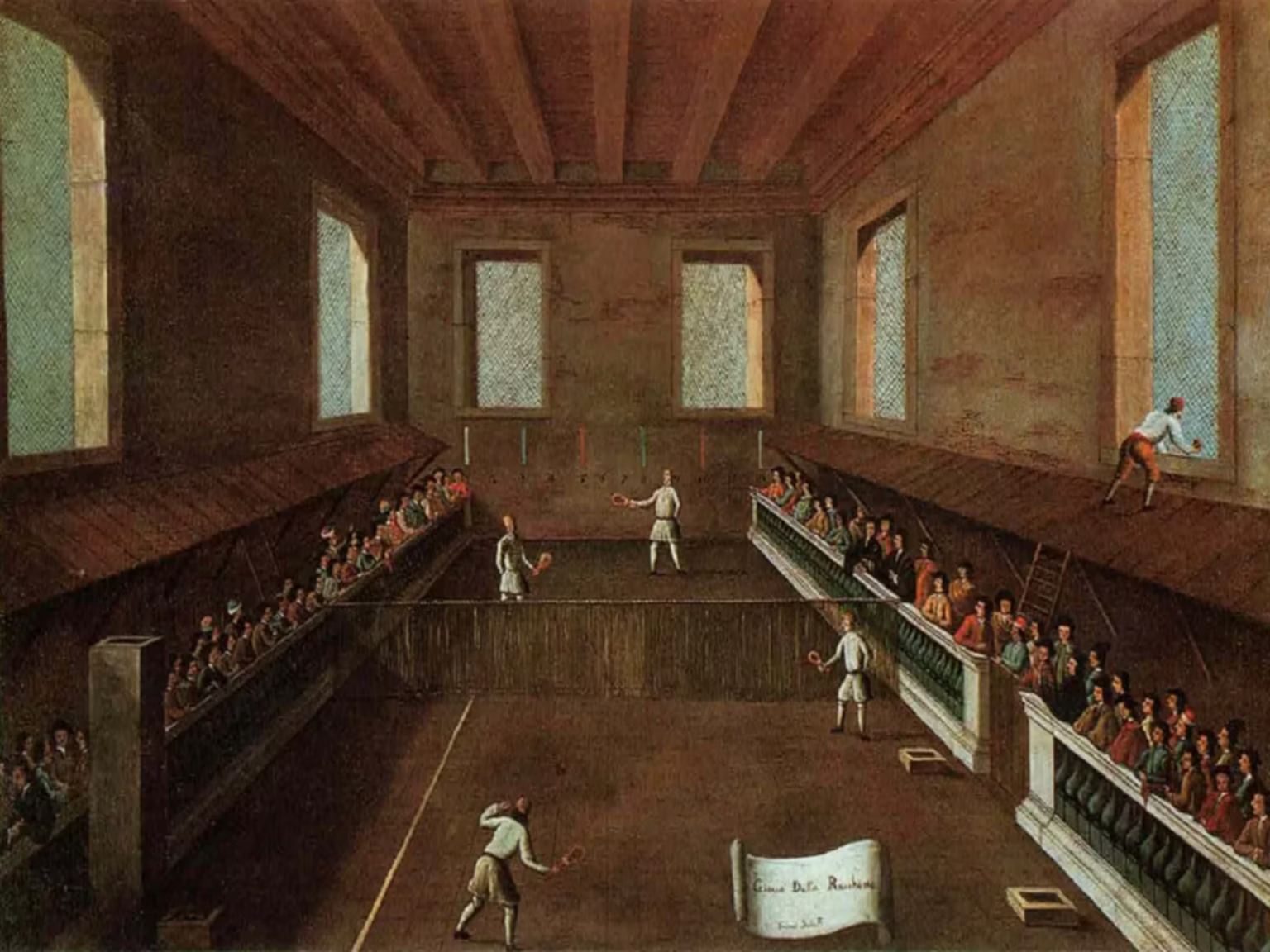

Only the giuoco della racchetta alla corda — the tennis like games — were played in custom-made indoor facilities. There’s still a Calle della Racchetta in Venice, where one of these places was in the 1700s.

Much of what we have from Venetian written sources, are just small notes of activities that happened in specific places, and at times, even notes in property records.

Giuseppe Tassini, in his Curiosità Veneziane, cites such a note by a Girolamo Ruzzini: “I live in the San Cancian district, in a house of my property near the Racchetta in Biri, at the Fontadamente Nove, just under the attic.”

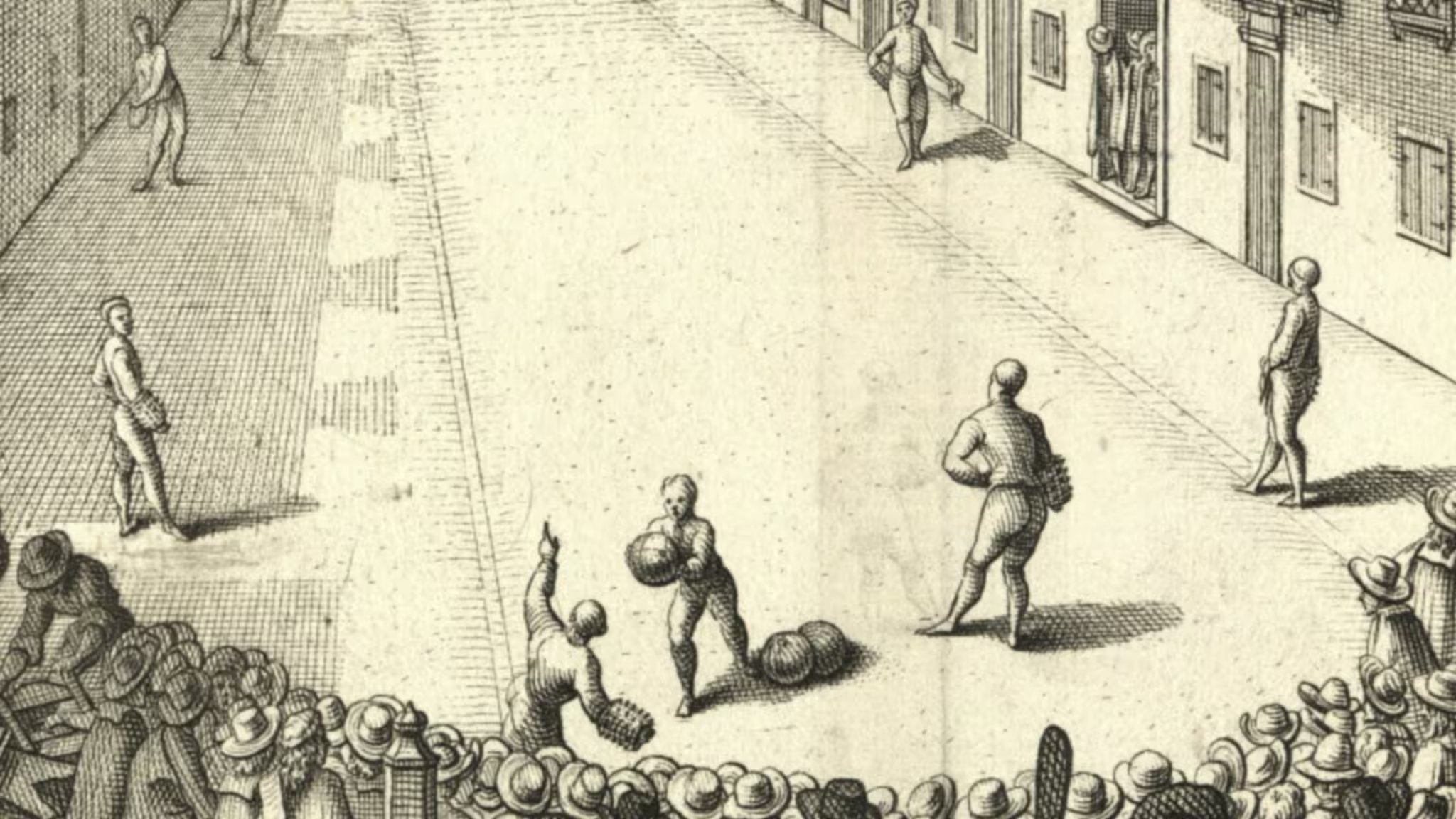

What we do have in Venice, are works of art — engravings and paintings — depicting ball games in various places in Venice, mostly from the 1700s.

Well-known artists from the period — like the printer and engraver Ludovico Lovisa, and the painters Gabriel Bella and Giovanni Grevembroch — have all left us works, where ball games feature, and sometimes prominently.

Related articles

- The game of Pallone

- The game of Calcio

- The game of Corda or Racchetta

Related images

- Giuoco del calzo — Habiti d’huomeni et donne venetiane — 35

- Nobile alla Rachetta — Nobleman playing racchetta — Grevembroch 1-94

- Nobile al Giuoco del Calcio — Nobleman at the game of Calcio — Grevembroch 1-87

- Nobile al Giuoco del Pallone — Nobleman playing at ball — Grevembroch 1-89

From Venetian Stories

Bibliography

- Colasante, Gianfranco. Antichi giochi italiani in Enciclopedia dello Sport. Treccani, 2004. [more] 🔗

- Nonni, Giorgio. SCAINO, Antonio in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani – Volume 91. Treccani, 2018. 🔗

- Scaino, Antonio. Trattato del giuoco della palla di messer Antonio Scaino da Salò, diuiso in tre parti. Con due tauole, l'vna de' capitoli, l'altra delle cose piu notabili, che in esso si contengono. In Vinegia appresso Gabriel Giolito de' Ferrari, et fratelli, 1555. [more] 🔗

- Tassini, Giuseppe. Curiosità Veneziane ovvero Origini delle denominazioni stradali di Venezia. 1863. [more] 🔗

Leave a Reply